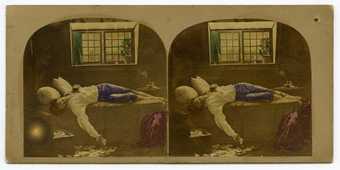

Fig.1

James Robinson

The Death of Chatterton 1859

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

Many artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci, understood that the world appears to us in three dimensions because our two eyes see from two slightly different angles (look at your hand with one eye covered, then the other eye covered, and you will see it move and alter slightly). Our mind combines these two views to perceive depth. Leonardo concluded that even the most realistic painting, being just one view, can only be experienced in two dimensions.

Nearly 350 years later, in London, the Victorian scientist Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875) took up the challenge. In 1838, he showed that a pair of two-dimensional pictures represented from slightly different viewpoints, brought together in his ‘stereoscope’, could appear three-dimensional. William Fox Talbot announced his technique of print photography a few months later and soon photographs were being taken in pairs for this purpose. Within a decade special cameras and viewers were invented; stereoscopes and stereographs were soon available worldwide. In 1859, Oliver Wendell Holmes’s essay ‘The Stereoscope and the Stereograph’ celebrated the invention:

The two eyes see different pictures of the same thing, for the obvious reason that they look from points two or three inches apart. By means of these two different views of an object, the mind, as it were, feels round it and gets an idea of its solidity. We clasp an object with our eyes, as with our arms, or with our hands.

Stereographs sold for a few shillings and people of all classes collected them for education and for pleasure. Small hand-held stereoscopes allowed them to gaze on faraway countries, mechanical inventions, comic incidents, beauty spots, zoological or botanical specimens or celebrity weddings, in the comfort of their homes. Three-dimensional images of famous sculptures were especially successful and Dr Brian May’s and Denis Pellerin’s new book, The Poor Man’s Picture Gallery: Stereoscopy versus Paintings in the Victorian Era (2014) has drawn attention to stereophotographers’ engagement with famous paintings of the age. Tate Britain’s display of some of the stereographs in Brian May’s collection creates a dialogue between these and celebrated Tate works, six of which are discussed here. It also introduces the photographers who, with rapidity and invention, took up this new medium.

The phrase ‘poor man’s picture gallery’, borrowed from print-making, appeared in The Times newspaper in 1858 in an article speculating on making stereographs of ‘our most remarkable pictures’. The writer did not think of these as mere imitations: ‘So solid and apparently real’, they would have ‘added a charm never dreamt of by their producers’, the original artists. Interestingly, the writer was discussing attempts to make stereographs from the paintings themselves because, he or she regretted, that such elaborate compositions could never be recreated in real life; ‘No exertion could gather together the characters with the requisite expression and all the adjuncts of suitable scenery…and retain them still until they were fixed by the camera’. This assertion was incorrect.

In 1855, the French photographer Alexis Gaudin (1816–1894) saw the Scottish scene from the Jacobite Rebellion, The Order of Release, 1746 [N01657] (fig.2) by John Everett Millais (1829–1896), at the first Exposition Universelle in Paris. A woman carrying a sleeping child comforts her wounded husband, a defeated rebel, while handing an order for his release to a gaoler. Shortly afterwards, Gaudin made a stereograph, the rare surviving examples of which bear no title, which posed a young woman, child and two men in the same attitudes (Untitled, after Millais, The Order of Release, c.1855, fig. 3) [X54966].

Fig.3

Alexis Gaudin

Untitled, after Millais, The Order of Release c.1855

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

Millais’s subject may have appealed to the Frenchman because of its theme of revolution (the Jacobites had been supported by France) and he may have hoped to capitalise on the painting’s popular success. It is notable too, however, that the picture is an example of Pre-Raphaelite realism, not just in appearance, but in the emotions expressed in pose and expression. Millais’s figures were, moreover, renowned as portraits of real people. Pre-Raphaelite painting was a challenge to photography, which Gaudin took up.

Gaudin’s stereograph was not a copy of Millais’s composition; it was a response to it. His image combined a backdrop painted in the conventional way behind the figures with real furniture and a door jutting out in front. Such round and rectangular geometric objects became common in stereographs because they created clear three-dimensional shapes. Like Millais, Gaudin used real models. They express the sternness, despair and stoicism of the gaoler, soldier and wife. The child’s bare legs and feet and head dropping on the mother’s shoulder indicate that s/he is sleeping, innocent of the tense exchange. The dog is probably an example of taxidermy as a real one is unlikely to have stayed still while the photograph, which would have been exposed over several seconds, was taken. Since they were taken and developed, the pictures have been hand-coloured.

Differences between the painting and the stereograph adapted Millais’s image to the new medium and new ideas. The gaoler could be resting the hand holding the order against the rebel’s shoulder to avoid moving and blurring the image, or Gaudin may have liked the juxtaposition of the document of release with the window indicating the outside world. The little dog is less romanticised than Millais’s loyal, silky specimen. It would have been recognisable at the time as a typical British terrier breed, a working dog similar to Bullseye, familiar from Phiz’s illustrations to Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837). This proletarian touch is compounded by the dog’s apparent interest in the empty food bowl.

Gaudin’s image could conjure reality in ways not available to Millais. Unlike painting, stereographs exclude things outside the frame. When the eyes come close to the stereoscope lenses and manage to bring the image into focus they experience the sudden sensation of being in the picture. Even the tiny scale of the scenes imitates the scale at which distant objects are experienced in life (to get a sense of this, look at a person on the other side of the room and holding your hand near your eye line up your forefinger with their head and your thumb with their feet). This characteristic provided Gaudin with a different way to explore Millais’s theme of imprisonment. The painter created an enclosed feeling for the viewer with a claustrophobic shadowy shallow space. The stereographer used a deeper room so that when seen through the viewer the figure, and the viewer, are enclosed within its walls.

Stereography was a new art. Gaudin’s stereograph can be seen exploring its distinctive characteristics, the actuality of figures and its immersive three-dimensionality, to bring the Pre-Raphaelite painter’s composition to life in new ways. This complexity was admired at the time: ‘It is a mistake to suppose one knows a stereoscopic picture when he has studied it a hundred times’, Holmes advised. Tate Britain’s display provides the opportunity to view originals with and without the stereoscopic viewer, and examine and appreciate their distinctive approach.

The problems and possibilities of realism were fundamental to 19th-century science and literature as well as the arts. It underpinned the dialogue between painters and stereographers. Even painted subjects from history and literature represented by stereographers appear to have been chosen for their familiar, everyday aspects. This shared realism reflected and therefore appealed to 19th-century audiences and was essential to the medium’s success. In 1854 The London Stereoscopic Company was set up on Oxford Street to sell stereographs and stereoscopes. Its first catalogue (1856) advertised scenes as ‘Miscellaneous Subjects of the “Wilkie” character’, referring to the most famous genre painter of the day, Sir David Wilkie. Wilkie’s younger rival, William Powell Frith (1819–1909), and Welsh photographer Frederic Jones (1827–date not known), a manager of the London Stereographic Company, recreated one of his most popular paintings, Dolly Varden (figs.4 [T00041] and 5). Frith’s composition was taken in turn from Charles Dickens’s (1812–1870) classic realist novel Barnaby Rudge (1841). It drew on the popularity of the author and book, and was intended to reach a similarly broad audience in the form of engraved prints. Although Dickens’s story was set in the 18th-century, the episode Frith chose, in which Dolly came across a man when she was alone in the woods and laughed bravely, appealed to modern preoccupations with women’s vulnerability and independence. Both Frith’s and Jones’s pictures placed the viewer in the position of the approaching man, but only Jones’s three-dimensional Dolly offered the spectator the opportunity to ‘clasp an object with our eyes, as with our arms, or with our hands’, as Holmes put it, as her predator does in the book. Fortunately, Dolly eventually eluded his attentions.

William Powell Frith

Dolly Varden (c.1842–9)

Tate

Fig.5

Frederic Jones

Dolly Varden 1858

Two photographs, albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

One of the most famous paintings of Victorian times was Chatterton, 1856 (Tate, [N01685] fig.6) by the young Pre-Raphaelite-style artist, Henry Wallis (1830–1916). Again, the tale of the suicide of the poor poet, Thomas Chatterton, exposed as a fraud for faking medieval histories and poems to get by, had broad appeal. Chatterton was also an 18th-century figure, but Wallis set his picture in a bare attic overlooking the City of London which evoked the urban poverty of his own age. The picture toured the British Isles and hundreds of thousands flocked to pay a shilling to view it. One of these was James Robinson, who saw the painting when it was in Dublin. He immediately conceived a stereographic series of Chatterton’s life. Unfortunately Robinson started with Wallis’s scene (The Death of Chatterton, 1859, fig.1). Within days of its publication, legal procedures began, claiming his picture threatened the income of the printmaker who had the lucrative copyright to publish engravings of the painting. The ensuing court battles were the first notorious copyright cases. Robinson lost, but strangely, in 1861, Birmingham photographer Michael Burr published variations of Death of Chatterton with no problems. No other photographer was ever prosecuted for staging a stereoscopic picture after a painting and the market continued to thrive.

The relationship between photography and painting went two ways. In the mid 1850s, Frith began to use photographs to help him paint elaborate and up-to-date scenes on a very large scale. Lively descriptions of racegoers at Epsom often appeared in popular magazines such as Punch (1949) and Dickens’s Household Words (Epsom, 1852,) and between 1856 and 1858 he created a panorama of the crowds, Derby Day (Tate N00615). It caused a sensation. Its quality of reflecting its modern audience is clear from a contemporary comment from the Birmingham Daily Post:

Frith’s picture will conjure around it as great a crowd of gazers as any to be found even on the most crowded part of the racecourse.

William Powell Frith

The Derby Day (1856–8)

Tate

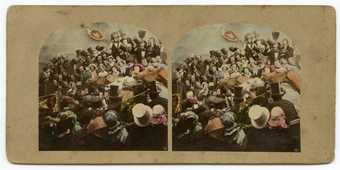

Stereography had the potential to take the viewer inside the crowd’s jostling and excitement. ‘The elbow of a figure stands forth so as to make us almost uncomfortable’, as Holmes observed. To this end, the London photographer Alfred Silvester (1831–1886) published two series based on the Epsom Races, National Sports, The Race-course [N00615] (fig.7) of which there are several variations echoing the different scenes within Frith’s painting, and The Road, the Rail, the Turf, the Settling Day (1859) a series of five. They were the portrait shape required by the stereoscope rather than panoramas like Frith’s painting, but Silvester squeezed in dozens of people. The Turf (fig.10) contained an astonishing 60 gesticulating figures in front of a painted backdrop of more distant crowds. Carriage wheels and cylindrical top hats occupy the foregrounds to enhance the three-dimensional effect.

Fig.8

Alfred Silvester

National Sports, The Race-course 1 1858

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

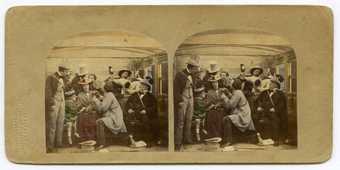

Fig.9

Alfred Silvester

The Road, the Rail, the Turf, the Settling Day (The Rail Second Class) 1859

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

Fig.10

Alfred Silvester

The Road, the Rail, the Turf, the Settling Day (The Turf) 1859

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

Like Frith, Silvester used dress to identify characters. The first variation of The Race-course (fig.8) shows high-spirited aristocrats in top hats. One, in a white topper particularly fashionable as holiday wear, subsides on the ground with a bottle. The frills and decorated bonnets of the young women that gather around their carriage would have been recognised at the time as a sign of potential flirtation. The banjo player in black face paint and waistcoat and check trousers did not appear in Frith’s painting. He was an increasingly familiar figure of the 1850s in which entertainers mimicked a stereotype of the black minstrel dandy. He reflects the new enthusiasm across all classes for Afro-American songs such as the ‘Camptown Races’, still sung at sporting events today.

Silvester expanded Frith’s narrative in time as well as content (moving pictures were still 40 years away). The Road, the Rail, the Turf, the Settling Day began with the exodus from London to Epsom Downs and ended with the settlement of bets. This narrative momentum was complemented by motion within the pictures. In The Road, aristocrats ride in their fine carriages while in The Rail (Second Class) (fig.9) and The Rail (Third Class) the less well-to-do travel on the new railway from London Bridge to Sutton, opened in 1847. The Turf shows three horses (sculpted from papier mâché and rather reminiscent of those in the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum) plunging headlong through the crowd. Further movement is contributed by the people. In each, Silvester orchestrated incessant activity in poses which betray no hint that they were held for several seconds. The Turf is the most spectacular, where all 60 people cheer and gesticulate. In The Rail (Second Class) a man kneels solicitously offering refreshment to a woman who appears to have fainted. Her child and others look on while an older gentleman (whose covered nose suggests he may be suffering from syphilis) shows his disapproval. The action continues into depth; in the background two men fight with bottles and a white top-hatted figure looms troublingly over a young girl.

Such photographs informed and challenged the naturalism of Frith’s painting and influenced others of the period. William Maw Egley’s (1826–1916) Omnibus Life in London (1859, [N05779] fig.11) depicted the discomforts, intrusions and intrigues of mass transport from a viewpoint within – or just outside – the carriage (an omnibus in this case, introduced 1826) which envelops the observer in a similar manner to Silvester’s The Rail (Second Class).

Similarly, a series by James Elliott (1833–?) charting the aftermath of the Derby appears to have pre-empted The Last Day in the Old Home 1862 (Tate, [N01500] fig.13) by Robert Braithwaite Martineau (1826–1869). Elliott’s One Week after the Derby extended Frith’s Derby Day into the future to show an auctioneer assessing the belongings of a family ruined by the races. The Last Look (fig.12) shows them leaving their house. Lot numbers have been attached to the furniture and in the background a servant, who has also lost her home, weeps. A horse print on the floor hints at the husband’s extravagant habits and only the grandmother, wife and daughter look back with regret. The last picture, Sold Up, shows the auction. The doll’s house which the little girl must to leave behind, a miniature replica of her home and her aspirations for the future is placed poignantly in the foreground. These narratives and motifs had been widely used in literature and cartoons since the time of William Hogarth, but Martineau’s image of a middle-class family forced to sell their home is close to Elliott’s The Last Look. Martineau adopted a photographic composition, figures enclosed within a room cluttered with clues to both narrative and depth. A stereograph-style view into another space shows men assessing possessions.Lot numbers are attached to the furniture. Another horse image suggests gambling. Once more, the women show regret while the husband appears unconcerned, cheerily leading his son down the same path.

Fig.12

James Elliott

The Last Look 1858

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

Robert Braithwaite Martineau

The Last Day in the Old Home (1862)

Tate

Stereographic techniques of arranging real figures in compositions that were at once carefully composed and naturally spontaneous were particularly pertinent to Pre-Raphaelite painters, who observed and used friends and acquaintances as models in inventive and expressive new poses. Michael Burr was skilled at intimate scenes; The Death of Chatterton was typical of his use of an unusually shallow, portrait-like space. In 1866, Burr’s Hearts are Trumps (fig.14) photographed three women in modern dress. They interact casually around a card table, and one regards us directly, but they are at the same time artfully positioned equally close the picture plane. This created a natural effect while keeping them the same length from the camera to avoid the distortions that a lens gives to near objects at different distances. Six years on, Sir John Everett Millais adapted the stereograph’s composition in his own Hearts are Trumps (1872, Tate, [N05770] fig.15). He might have incorporated its informal effect to challenge accusations that had recently appeared in the press that he could not represent modern beauties in contemporary fashion. The life-like size of Millais’s image fills the field of vision with the same impact that the encompassing scene presents in the stereoscope.

Fig.14

Michael Burr

Hearts are Trumps 1866

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection of Brian May

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

Hearts are Trumps (1872)

Tate

Millais’s Hearts are Trumps may have nodded to the alternative stereographic art form, but it did not defer to it. His colour harmonies are infinitely more nuanced than Burr’s hand-tinted photograph. The brushwork whips up extra vivacity and asserts the painter’s individual touch. Nonetheless, Oliver Wendell Holmes argued that stereography had its own artistic possibilities:

The very things which an artist would leave out, or render imperfectly, the photograph takes infinite care with’; there will be ‘incidental truths which interest us more than the central object of the picture… every stick, straw, scratch…look at the lady’s hands. You will very probably find the young countess is a maid-of-all-work.

Robinson’s The Death of Chatterton (fig.1) illustrates the way this uncanny quality distinguishes the stereograph from even the immaculate Pre-Raphaelite style of Wallis’s painting of the same subject. The stereograph represented a young man in 18th-century costume on a bed. The backdrop was painted, but the chest, discarded coat and candle were real. Again, the light and colour appear crude in comparison with the painting but the stereoscope records ‘every stick, straw, scratch’ in a manner that the painting cannot. The torn paper pieces, animated by their three-dimensionality, trace the poet’s recent agitation, while the candle smoke, representing his extinguished life, is different in each photograph due to their being taken at separate moments. The haphazard creases of the bed sheet are more suggestive of restless movement, now stilled, than Wallis’s elegant drapery. Even the individuality of the boy adds potency to his death.

Holmes’s 1859 article confirms that, in its earliest moment, stereography was thought of in relation to realist painting. ‘The first effect of looking at a good photograph through the stereoscope is a surprise such as no painting ever produced,’ he declared, ’the mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture.’ He provides a sophisticated understanding of the artistic possibilities of the precocious technology, at the date at which the stereographs on display at Tate Britain were made, but it is the stereographs themselves which bear this out.

- BP Spotlight: ‘Poor man’s picture gallery’: Victorian Art and Stereoscopic Photography runs until 1 November 2015