Charles Wellington Furse

Diana of the Uplands (1903–4)

Tate

Diana of the Uplands (fig.1) stands on a windswept moor, frozen in time, her hat threatening to fly off, greyhounds straining at the leash. The folds of her satin coat seem blurred as the wind engulfs them. The epitome of Edwardian elegance and painterly panache, this portrait by Charles Wellington Furse (1868–1904) of his wife Katharine encapsulated an era and was once considered to be one of the treasures of the Tate Gallery, rivalling Millais’s Ophelia in popularity. In 1927, it was among the pictures selected by the Board of Education for public elementary schools alongside canonical works such as Velázquez’s Infanta Margarita Teresa, Turner’s Fighting Téméraire and Whistler’s The Artist’s Mother, ‘because it is worthwhile that a child should grow up in daily contact with some of the pictures he will hear about all his life if he hears about pictures at all’.1 Diana of the Uplands also featured in G.K. Chesterton’s two-volume Famous Paintings (1912 and 1913), with no suggestion that the high regard in which it was held might not stand the test of time. Two further portraits in the Tate collection, Ethel and The Sisters (figs.2, 3), both by the now unknown Ralph Peacock (1868–1946), also figured in Chesterton’s book and in the early 20th century they were popular at the Tate Gallery, when it was still a branch of the National Gallery, and administered by it. Yet these paintings, like the other exhibits in this display, have seldom if ever been on show in the past few decades.

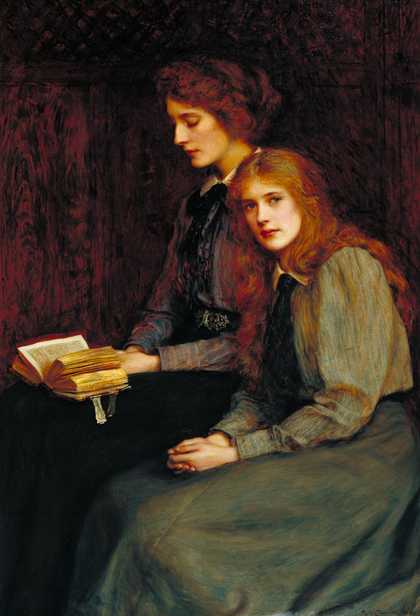

Ralph Peacock

The Sisters (1900)

Tate

France and Britain

At the turn of the 20th century, Paris was thought to lead the way in the visual arts, in both training and innovation. Typically, most of the twelve painters and three sculptors represented in this display studied in Paris, often after initial training in Britain. This was particularly the norm for sculptors, as the teaching offered in England until the 1870s focused on drawing rather than modelling: Sir George Frampton (1860–1928) studied under Antonin Mercié, and James Havard Thomas (1854–1921) under Pierre-Jules Cavelier. The Frenchman Edouard Lantéri (1848–1917), who arrived in Britain in 1872, had also trained with Cavelier.

Of the painters, only Ambrose McEvoy (1878–1927), ironically singled out in reviews for his French style, Ralph Peacock, the Austrian Emil Fuchs (1866–1929), the Anglo-American artist Sir James Jebusa Shannon (1862–1923), and Charles Haslewood Shannon (no relation,1863–1937) did not study in France. This last went there to meet Puvis de Chavannes, who discouraged him from studying in Paris in favour of developing his talents in England. The ‘finishing school’ par excellence for painters was the Académie Julian, where Robert Brough (1872–1905), Charles Wellington Furse, John Lavery (1856–1951), Charles Kerr (1858–1907), the Frenchman Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942) and Hungarian-born Philip de László (1869–1937) all did part of their training. As Robert Jensen puts it, ‘who did not study at Julian’s at the end of the nineteenth century?’2 The Anglo-Irish Gerald Festus Kelly (1879–1972) did not, although he studied and lived in Paris for a while. The Burlington Magazine reviewer of the Autumn Salon exhibition remarked: ‘There is no very striking work by a new-comer, except perhaps the portrait of a woman by a Mr. Kelly, presumably an American, since his work shows marked French influence.’3

It would be wrong, however, to assume that these artists had any ambition to emulate the French, that their styles were derivative, or that the relationship with France was one-sided. As the Burlington reviewer implies, Paris was the hub of an international art scene. The Palais du Luxembourg, which housed a museum of contemporary painting and was often cited as an incentive toward the establishment of a National Gallery of British Art (now Tate), was active in collecting British painting. Between 1900 and 1915, works by Lavery, Kelly, Charles Shannon and de László were acquired by the French state. Many of the artists in this display were members of, or exhibited at, the New English Art Club (NEAC), founded in 1885 as an alternative exhibiting venue to the Royal Academy. Despite the allegiance to impressionism of most of the NEAC’s founding members, they thought of themselves as British artists. Furse, in particular, was at the heart of debates around impressionism in Britain at the turn of the century, and with George Moore and Walter Sickert he argued that it was not specifically French, and could be traced back to British traditions, not least grand manner portraiture as exemplified by Reynolds and Gainsborough. The grand-scale composition and flamboyance of Diana of the Uplands pays homage to 18th-century British masters – especially at a time when there was a commercial and artistic revival of interest in Gainsborough, Reynolds and Romney – though its subject and brushwork were unmistakably modern.

A different modernity

In the light of early 20th-century artistic developments including those under the wider banner of modernism (such as fauvism, expressionism and cubism), it may be difficult today to appreciate that these artists were considered by their contemporaries to be modern. But critics and public came to prefer modernism over academic style. That practice was then equated with naturalism and rejected as stale, conservative and outmoded.

The American painters James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), international figures working in England, dominated portraiture during the fin-de-siècle and influenced the painters included in Forgotten Faces. They too went out of fashion in the 20th century, perhaps because their work eludes easy classification. Over the last 30 years their reputations have been re-established largely through major exhibitions and monographs.

Robert Brough

Fantaisie en Folie (1897)

Tate

Whistler influenced the style of John Lavery in the 1890s and the early work of Kelly, McEvoy (whose father was a friend of the American painter), Furse and the Scot Robert Brough. Even though the latter two were to become Sargent’s protégés, as evidenced by their handling of paint, Brough’s Fantaisie en Folie (fig.4) is clearly influenced by Whistler’s misty brushwork and low-keyed palette. A woman with a haughty poise and striking profile looks down on a laughing Buddha, touching the statuette with her pendant. The painting’s title has led to many speculative translations suggesting madness but a closer equivalent is ‘Unbridled Fantasy’. The misplaced focus on insanity has been a distraction from the musical meaning of ‘fantasy’ and the possible connection to Whistler’s ‘Symphonies’ and ‘Nocturnes’ and to aestheticism. This would account for the enigmatic quality and subject of the painting, probably intended to be read as mood and feeling. Fantaisie en Folie blurs the boundaries between portraiture and figure painting, and belongs to a ‘genre … representing the aesthetic moment… which showed familiar people having superior thoughts, in pictures which portrayed the beauty of contemplation’ which can be traced back to Whistler’s Symphony in White, no. 2, The Little White Girl (fig.5).4 As McConkey points out, ‘hers is the first of many languid arms which reach out for the aesthetic object’,5 a blue china pot in this instance, or the Chinese statuette in Brough’s painting. Fantaisie en Folie was exhibited in Paris, Glasgow, Vienna, Munich and St Louis, Missouri. Like Furse, who died of consumption in 1904 at the age of 36, Brough’s promise was unfulfilled. He died at 34 following a train crash in Sheffield. Their early deaths may explain why both are neglected figures in British art. In accordance with Brough’s will, Fantaisie en Folie, which he regarded as his masterpiece, entered the Tate collection in 1905, the year he died.

Ambrose McEvoy

The Ear-Ring (exhibited 1911)

Tate

Ambrose McEvoy’s early work The Ear-Ring 1911 (fig.6) also depicts an aesthetic moment, though here the object of contemplation is the young woman herself, mediated by the mirror facing the viewer. McEvoy’s French sitter, Anaïs Folin, was his son’s governess and the artist’s favourite model at the time. He made hundreds of drawings of her between 1911 and 1912, and praised her ability to sit completely still. This quality would also have been appreciated by painter Gerald Brockhurst, whom she later married. The Ear-Ring was first exhibited at the NEAC in 1911, and presented to the Tate Gallery by C.L. Rutherston in 1917, by which time McEvoy had become a fashionable portrait painter. It remains one of his best-known pictures. His brushwork later broadened, often to create iridescent effects, but he was criticised for painting for money and his reputation declined. The Ear-Ring was still popular when it was among 330 works selected for the exhibition of British painting at the Louvre in 1938. Of course, Reynolds, Gainsborough, Turner and Constable featured prominently, but a critic noted that ‘the eye is caught by such “inevitable” things as… “The Earring” by Ambrose McEvoy’,6 attesting to the painting’s status at the time.

Emil Fuchs

Sir Joseph Duveen (1903)

Tate

After Whistler, the strongest influence on painters included in Forgotten Faces remains John Singer Sargent, who came to England in 1886. His bold technique and handling of paint, perceived to be ‘impressionistic’, disconcerted at first, but he soon became the leading portrait painter of his generation, in England as well as the United States. Sargent was generous with his advice and his impact on other artists cannot be underestimated. Furse’s Diana of the Uplands is the clearest example of his influence in this display. Furse had taken a studio at 33 Tite Street in London, close to that of Sargent and, as he put it, ‘got a lot of tips’.7 As noted earlier, Robert Brough, was probably Sargent’s closest protégé (the American sat by his deathbed), but from 1897, Sargent also started giving guidance and tuition on paintin to Emil Fuchs, who had first trained as a sculptor. Fuchs became popular, especially with the royal family, and was the only artist to be granted permission to sketch Queen Victoria as she lay in state on the night of her death. He also designed Edward VII’s postage stamps and coronation medal. In his memoirs, Fuchs noted: ‘Some mornings [Sargent] would come in and, without saying much, would help me in painting a difficult passage from the model … Rather than explain a serious problem, he would take a brush and paint that piece and the difficulties would vanish under his touch. When I worked at his studio he offered me the free use of his colours and even his palette and brushes which lay about in profusion. Few artists can bring themselves to lend these objects without feeling it to be sacrilege. So dominant is Sargent’s personality in art, that it was bound to be reflected in the work of his friends.’8 Fuchs’s 1903 portrait of Sir Joseph Duveen (fig.7), one of the first major benefactors of the Tate Gallery, shows his talent at characterisation, while recent conservation work at Tate has revealed his fluid brushwork. He later found fame in the United States, where he moved permanently in 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War.

Technical mastery

Even though the artists included in the display did not belong to any movement, they have been associated with what has been called the ‘juste milieu’ (‘middle way’). Sargent was seen as Britain’s leading exponent of the ‘juste milieu’. That term does not so much refer to a unifying style as to a technique combining the innovations of impressionism with the clarity of academic painting. Unfortunately it suggests a compromise which does not do justice to the work of these painters, but it is nonetheless useful in explaining their success. The public came to admire the technical mastery and ‘performing bravado’ of Sargent and the British artists whom he influenced.9 As Jensen puts it: ‘demonstrably modelled and often heavily worked, their surfaces were read like records of the artist-genius at work’.10

Philip Alexius de László

Lady Wantage (1911)

Tate

An emphasis on technical prowess is especially evident in Philip de László’s portrait of the philanthropist Lady Wantage (1911) (fig.8). Though some would consider the work unfinished, it is what the artist called a ‘portrait study’ or ‘portrait sketch’, usually executed in a single sitting of two to three hours. Here de László captured Lady Wantage’s likeness on a Sunday morning in July 1911, on her return from church. He had previously executed a formal three-quarter length portrait of her. This work was painted, not as a commission, but for his own pleasure.

De László established a collection of portrait studies of various personalities and friends to many of whom he gave sketches. Because the unpainted areas of his work highlighted his brushwork and ability to capture a likeness, sketches became his trademark and were much in demand. They were slightly more affordable than a finished portrait, as de László commanded high fees: the highest recorded, for a double portrait of Mr and Mrs Larz Anderson, was 6,000 guineas in 1926 (the equivalent today of £300,000). With his fluid brushwork de László set out to capture his models’, psychology and personality. He usually favoured plain backgrounds to focus attention on his sitters. Although at one time James Jebusa Shannon was seen as Sargent’s most serious rival in England, it was de László who inherited his clientele when he settled in London in 1907, the year Sargent officially retired from portraiture. De László made frequent trips to Paris and the United States, and painted four American presidents, most of the aristocracy and crowned heads of Europe, popes, dictators, self-made men, scientists and fellow artists. When he died in 1937, his international reputation as a technical wizard was unchallenged, yet few today know his name.

Ralph Peacock never achieved fame like de László’s; his inspiration seems to have dried up, and appreciation of his work declined. The darling of art critics at the onset of his career, he had early success: a gold medal at the RA Schools, the Creswick Prize in 1887, a gold medal in Vienna in 1898 and bronze at the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1900. Yet despite his technical abilities, he was never made an ARA and was chiefly known in his lifetime for Ethel 1897 and The Sisters 1900. Ethel Brignall, Peacock’s future sister-in-law, features in both portraits and, with his future wife Edith, in The Sisters. Peacock became a successful portrait painter, especially of children, but the wood panelling in the background of the Tate’s two portraits appears as the backdrop in too many of his works.

Technical skill was not the sole attribute of these painters. The sculptor James Havard Thomas, who is difficult to categorise, lived in Italy for many years, developing a quasi-scientific method to achieve a faithful representation of his models. He would place his sitters in a sort of wooden cage which allowed him to measure sections of the body in the exact pose he had chosen, to ‘regulate the infinity of movements to which it is constantly subjected’. Rendering the skin’s surface in minute detail, with which many sculptors of his generation were preoccupied, did not interest him. He sought instead to convey the physical presence of his models through an understanding of the muscles and mechanics of the body. His marble bust of Mrs Asher Wertheimer 1907, donated to the Tate Gallery by her husband in 1908, captures not so much a fleeting expression as her bodily presence. Thomas was one of the few British sculptors of his generation to carve marble himelf. In the 1910s, the younger Jacob Epstein would lay the foundation of a new sculptural tradition in Britain also based on direct carving but, unlike Thomas, looking back to African tribal art rather than classical antiquity.

Personal connections

Charles Henry Malcolm Kerr

The Visitor (exhibited 1905)

Tate

Fuchs’s portrait of Duveen and Thomas’s bust of Mrs Wertheimer are the only portraits in this display that were commissioned. Most reveal a personal connection between artist and sitter, which allowed for greater experimentation. The title of Furse’s portrait of his wife, Katharine, Diana of the Uplands, suggests other genres including history painting – ‘Diana’ refers to the classical goddess of hunting – and landscape painting – the rather archaic English term ‘upland’ meaning higher ground. The bond between husband and wife also meant that, to achieve the desired effect, Furse could be more demanding of Katharine than he would have been with a patron. As she noted in her memoirs, the picture was painted at the couple’s home in Yockley, Surrey, not outdoors. The painter’s stepmother Gertrude ‘was brought in to try the bellows under the skirt, which was tied up to a support to help the “wind”.’ A skilled carver, Katharine produced the ornate wooden frame for this portrait, making it a collaborative work on more than one level. Diana of the Uplands is the only work in this display to have been purchased for the nation, two years after Furse’s death. It was acquired from his widow via the National Gallery’s Clarke Fund. (At the time, the Tate Gallery did not have its own acquisition budget, and purchasing was controlled by the National Gallery.) Charles Kerr’s The Visitor (fig.9), an intimate portrait of his wife Gertrude, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1905 as ‘Mrs Charles Kerr’, is typical of the way portraiture blended with other genres at the turn of the century. The backlighting, glimpse of an interior, suggestion of another presence and the woman’s mourning dress, suggest a ‘problem picture’. Such paintings, prominent in the late Victorian era but still popular later, offered an ambiguous narrative open to interpretation.

Lavery’s La Mort du Cygne 1911 (fig.10) allocates as much space to the theatrical setting as to the figure of the dancer, Anna Pavlova, who won fame with the Imperial Russian Ballet and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. It portrays her as the dying swan, a role she created. In fact it is more a portrait of Lavery’s wife than of Pavlova. In 1910 Lavery had made two portraits from life of the dancer as a Bacchante, but she left on tour before he could complete the painting, so he used Hazel Lavery, assuming that, the two women would look similar in stage make-up. Pavlova’s husband Victor Dandre thought the painting a poor likeness, but Lavery was more interested in the opportunity for artistic experiment. The dancer’s pose and the setting were imaginary. Her tilted head and elongated neck against the dark background are mirrored by the swan to theatrical effect. The almost monochromatic palette, which suggests both the fading light and the swan’s death as the curtain is about to fall, add to the unusual quality of the work.

Sir John Lavery

La Mort du Cygne: Anna Pavlova (1911)

Tate

George Frampton’s memorial to etcher and Punch illustrator Charles Keene (1896), James Jebusa Shannon’s portrait of his friend the draughtsman and caricaturist Phil May (1902), Lantéri’s posthumous bust of Alfred Stevens (1911), Blanche’s portraits of painter Charles Conder (1904) and novelist Thomas Hardy (1906), and Kelly’s portrait of his friend the writer Somerset Maugham (The Jester, 1911) all reveal affinities with fellow artists, many also now forgotten or neglected, if not in name at least in appearance. Even Thomas Hardy’s features are little recognised today and, if Somerset Maugham is best remembered as an old man as depicted by Graham Sutherland (1949, Tate), the dapper young man in Kelly’s portrait may come as a surprise.

When they met in France, Kelly was struck by Maugham’s pale complexion and eyes ‘like little pieces of brown velvet – like monkey’s eyes’11 which he captured in this portrait, set against a Burmese cabinet and coromandel screen that Kelly had brought back from his travels. This is the third of seventeen portraits Kelly painted of his friend, while he appeared in several of Maugham’s novels: Kelly was one of the models for Griffiths and painter Frederick Lawson in Maugham’s Of Human Bondage. Maugham apparently called on Kelly at his studio in William Street to show him his new top hat, and the artist decided to capture him then and there. Kelly later stated that the portrait was ‘just done casually. It amused me to paint the cabinet and the screen, and Maugham was introduced as a diversion in the foreground’. This image encapsulated the elegance of the era, and the painting was exhibited worldwide. It was acquired by the Tate Gallery in 1933 through the Chantrey Bequest. Kelly stayed at Windsor Castle during the Second World War to paint the Royal Family, and later became President of the Royal Academy. Despite this, he was not thought important enough to have an entry in the Grove Dictionary of Art. He began broadcasting in the 1950s, giving lively introductions to Royal Academy exhibitions, but later sank into obscurity.

After two world wars and the development of a radically new pictorial language, works like those in this display were felt to be out of touch with the modern world. In due course, the Tate Gallery became separate from the National Gallery and, with its own acquisition budget, developed a collection strategy sometimes at the expense of earlier gifts and bequests. Some of the works in Forgotten Faces were overlooked, some, like The Sisters and Ethel, were sent to provincial galleries where they remained. . The condition of others, including Fuchs’s portrait of Duveen and the bust of Mrs Wertheimer, deteriorated and could no longer be exhibited: they have been restored for this display. It is hoped that these works can now be reconsidered, and may regain some of their former prominence.