Alan Davie’s activity as a painter is often described as resembling shamanistic artists of remote times engaged in conjuring up visions linked to mysterious and spiritual forces. His kaleidoscopic paintings are the result of an improvisatory process into the unknown, their gestures and biomorphic forms celebrating a world of imagination and beauty at odds with the common view of the alienation and disaffection of the post-war milieu. Harnessing his engagement with jazz, Zen Buddhism and prehistoric cultures, Davie’s images emerge from networks of spontaneous forms and symbols that often overlap and obscure each other until the final composition is revealed. From his abstract canvases of the 1940s and 50s that draw attention to the materiality of paint and the physical gesture of the artist to later works with their mystical symbols and text, Davie (who died in april 2014) demonstrated his commitment to art as a search for inner beauty that grows naturally with the rhythms of the mind and body. This display, showcasing all eight of Davie’s paintings in Tate’s collection as well as material from the artist’s personal archive, is a timely opportunity to reassess his unique visual language. This text uses these works to trace the development of Davie’s practice over the last 60 years, highlighting particular moments in his visual journey.

Davie, born in Grangemouth (on the River Forth) in 1920, is celebrated for being one of the first British artists after the Second World War to develop an expressive form of abstraction. He began as a poet and jazz musician before becoming a painter, combining these disciplines throughout his career. Having studied at Edinburgh College of Art (1938–40), his aspirations to be a painter were abandoned when he was conscripted into the Royal Artillery in 1942 and sent to an aircraft battery in the Warwickshire countryside near Kenilworth. Davie never experienced frontline combat and described these years spent surrounded by fields and trees as a crucial first encounter with nature. During this formative period Davie discovered the poetry of Walt Whitman and T.S. Eliot, whose prose is echoed in letters home as well as his own verses, bound by his father into book form and peppered with photographs and colourful illustrations. Compelled like Whitman to capture his emotions first-hand, Davie’s immersion with words would ultimately feed into the process and creative energy of his images:

How senseless it is

The way they dance

So monotonously around

In front of me

I watch them with my eyes

As I blow breathy music

From my saxophoneI play to the moon

Like a Chinese flautist

In the forest

The dancing figures change

To silver grasses tall

And waving gently

I no longer hear the sound

Of an out of tune pianoA smile is a beautiful thing

I answer with my eyes

And play the more beautifully1

Deciding that there was no career to be made from writing, Davie worked as a jazz musician and jewellery maker after being demobilised from the army in 1946. Ranging from primeval animals and birds to human and solid abstract forms inspired by Saxon and pre-Columbian design, Davie’s silver pieces are an early indication of the forms that would later appear in his paintings. Davie began teaching basic design in the jewellery department at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts led by the Scottish artist William Johnstone, where colleagues included artists Nigel Henderson, Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton and Patrick Heron. In 1961, Davie’s jewellery was featured in The International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery at London’s Goldsmith’s Hall, a milestone in the history of jewellery making in Britain where an impressive roster of international and British artists including Alexander Calder, Naum Gabo, Victor Pasmore and John McHale appeared in a section on ‘Modern Work by Sculptors and Painters’.2

The power and mystery of jazz, which Davie believed to be the creative medium of the 1940s, was a continual source in his search for ‘the mystery of life’. His painting process, which the artist compared to Paul Klee’s famous statement that drawing is ‘taking a line for a walk’, is not unlike that of a jazz musician improvising melody and rhythm. Since joining the Tommy Sampson Big Band in the late 1940s as a professional saxophonist (going on to make BBC broadcasts with the Cam Robbie band and releasing five albums of his own improvised music recorded in Cornwall during the early 1970s), Davie mastered a number of instruments and switched freely between saxophone, piano and painting, enjoying the liberation from linear time and losing himself through improvisation. ‘I can sit down at a piano and just play a few notes,’ Davie asserted, adding that, ‘Before I know it, I am entering a world of ideas which are presenting themselves to me out of the manipulation of sounds.’3 Like the musicians he admired – Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins – Davie’s free-flowing gestures and marks move with hypnotic intensity, his chaotic abstractions the pictorial equivalent of sound and movement with rhythm, melody and harmony.

Having relinquished painting to focus on jewellery making and jazz, in the spring of 1948 Davie and his wife Bili took up a deferred art school travel scholarship and set off around Europe. Unlike other British artists who made straight for Paris and stayed there, Davie ventured further afield. His experience of Switzerland, Italy and Spain was transformative, as revealed in the journals the artist compiled between April 1948 and March 1949 charting his encounters with art and nature and the development of his creative sensibility:

May 7, Paris

Surely that spiritual joy which flows in us from the vision of a fine work [of art] comes not from a mere arrangement of material forms… surely the illusive quality of beauty is something which exists outside space and matter, in a world of timeless spirit, and the picture is only a materialisation of such spirit… a manifestation of spirit felt by a creative genius and passed to us through its conducting medium of form, as a wire can conduct electrical energy from one matter to another. The true essence of spiritual beauty is indestructible and everlasting.

May 26, Switzerland

At last in the thick air I could see the dimly shining form of the Matterhorn, now clear of cloud, all lit with a supernatural whiteness in the night. My dreams were filled with its form… the great triangular pyramid pulled up to a bent-over top, all covered in pure snow… it is a thing as inexpressible as the moon and as mysterious and as full of awe.

June 3, Switzerland

The miracle that comes to pass; the light which gleams suddenly within me, the flash of true understanding, for a moment blinding me, then filling me with a complete joy and satisfaction; it is so difficult to define, yet it forces me to try.4

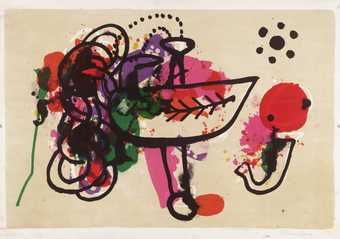

In Paris Davie was stimulated by the exoticism he saw in early Christian, Byzantine and Romanesque art which he found chimed with the spiritual intensity of his Celtic tradition, as well as modernist paintings by Picasso, Matisse and Arp. After hitchhiking to Switzerland and walking around the Matterhorn, the Davies went to Venice. Their arrival coincided with the 1948 Venice Biennale, the first after the war, where exhibitions showcasing the work of Paul Klee and Peggy Guggenheim’s collection of surrealist and contemporary American art inspired Davie to begin painting again. ‘This was a time when creative people in all the arts were striving for a “liberation”,’ he recalled, ‘a setting free of the natural pictorial flow of letting go – we had a vague notion that complete freedom would lead to infinite possibilities.’5 Back in his cheap lodgings Davie experimented with mono-type printing using automatic techniques and collage, placing ink between panes of glass and sheets of paper and scratching the paper with his fingers, the final image only visible once it was lifted away. Expressive in their own right, Night Sky on a Holiday 1948; Interested Sperm Around an Egg 1948; A Great Sound in the Heavens 1948 and Spirit over the Landscape 1948 (fig.1) were the foundation of Davie’s fascination with automatism, chance and the unexpected, their spindly, biomorphic forms suggesting the growth of microscopic life. Davie’s works on paper are less well known but have played a vital role in the development of his art, enabling him to liberate subconscious actions and ideas and generate new kinds of images.

Alan Davie

Spirit Over the Landscape (1948)

Tate

Alan Davie

Entrance to a Paradise (1949)

Tate

Entrance to a Paradise 1949 (fig 2) is a breakthrough painting made shortly after Davie’s return from Venice to an attic studio in New Barnet, London. Stimulated by what he had encountered on the continent, Davie set out to free himself from the conventions of picture making. Working quickly with boards and canvases packed around the walls and floor of his studio using large brushes and pots of liquid paint, he produced a body of work without any consideration for subject or form, discovering that images appeared to him quite unexpectedly. As a result, the surface of Entrance to a Paradise is richly layered. It has a dense grid-like structure from which individual shapes seem to emerge. Across its surface a web of signs and symbols appear to take on a life of their own, Davie’s rapid application of paint suggesting a composition open to chance and a visual world beyond the grasp of reason. With each layer new forms and gestures are made and others are buried. As the artist explained: ‘The process of painting was very distinctive – layer upon layer destroying what was underneath – and always working spontaneously and automatically – so of all the works done, very little was kept – only those images which happened in the rare magical moments when I was completely surprised and “enraptured beyond knowing”.’6 As always, the title Entrance to Paradise was given to the picture some time after it was painted, in this case suggesting a way in to a mysterious and joyous world of colour and light.

Alan Davie

Birth of Venus (1955)

Tate

During the early 1950s, a time when British artists had limited exposure to the latest painting from America, Davie earned the reputation of being the nearest thing in England to an American abstract expressionist. His visceral paintings including Birth of Venus 1955 (fig.3) bursting with wild, turbulent colour became associated with the so-called drip paintings of the American artist Jackson Pollock whose work came to dominate the post-war scene. Yet for Davie, Pollock’s method of dribbling and splashing paint onto canvases laid on the floor was a dead-end for painting: ‘Pollock shared with myself a passionate interest in the art of primitive peoples and this does show in the early work,’ he said. However, ‘the following of the idea of absolute freedom led inevitably to a dead end – such abandonment of “IDEA” was exciting up to a point, but the results became boring and in a strange way [Pollock’s] pure drip paintings became a kind of naturalism – like looking into the kind of tangle that one finds in bramble bushes… To me, art is a matter of making original magical things which has unique formal content… yet marvellous “science” of nature which makes the whole universe function.’7 Davie always maintained he was a Scottish artist and it is interesting to consider his work in the context of the abstract decoration of his Celtic tradition and the lively genre scenes of David Allan (1744–1796), Alexander Carse (c.1770–1843) or David Wilkie (1785–1841) that revel in the vitality of their country’s festive customs – rather than in that of modernist American painting. Imagery from other Celtic phenomena such as Pictish stones, the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels also proved to be important sources and counterpoints.

Reviewing his first exhibition in New York in 1956, the English critic and artist Patrick Heron presented Davie as part of a new generation of British artists including William Scott, Peter Lanyon, Keith Vaughan and Roger Hilton who were developing a new kind of painting that fused formal concerns with subject matter. For Heron, Davie’s splashes and drips were not like Pollock’s, the subject matter of his painting, but incidental marks that were a by-product of his intuitive process: ‘[N]ot only does the bespattered and encrusted surface of a Davie take on a positive richness, as of medieval jewellery or stained glass, but formal analogies appear… the froth of new buds or leaves seem to crystallise out of the swift, ragged calligraphy; there, flat blunt chunks of form resolve themselves into somewhat heraldic emblems of the human figure.’8 Writing in the early 1960s, the English art critic Robert Melville championed Davie’s work in the context of European surrealism, drawing attention to his ‘surrealist taste for juxtaposing the sacred and the sacrilegious’.9 For Melville, Davie’s early paintings went beyond their surfaces of gesticulatory brushwork and were sombre pictures suggesting the corners of imaginary rooms concerned with problems of space, comparable to Francis Bacon’s interiors. This is also suggested in the structure of Entrance to a Paradise or the artist’s recollection of temporary blindness suffered during a war-time illness in Black Mirror 1952 (fig.4) with ‘walls… composed of enigmatic boxes and screens which look like the apparatus for recording and controlling events taking place elsewhere…[weaving] an interest in science fiction into a highly personal sense of being on the threshold of unknown territory’.10

During the decades following the Second World War when principles of Zen Buddhism gained currency in the west, Davie became part of a new international generation of artists, writers and poets who developed an interest in eastern philosophy. While this associates Davie with the Beat Generation embodied in Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road 1957, it also drew on the English writer Aldous Huxley and potter Bernard Leach’s pre-war encounter with the writings of the influential English orientalist Arthur Waley, whose book Zen Buddhism and Its Relation to Art 1922 gave an important insight into the psychological conditions under which art is produced.11 As Waley described, Zen is principally concerned with things as they are without trying to interpret them, and is an attempt to understand the meaning of life resulting in total spontaneity and freedom without being misled by logical thought or language. As a result, Zen artists make images in a quick and evocative manner and are at one with their materials. Sacrifice 1955 (fig.5) was made the same year Davie read another important source of Zen philosophy, Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, published in English in 1953. It reaffirmed Davie’s ideas about art as a spiritual quest that could reveal universally accessible meaning. This aspect of Davie’s practice sets his work at odds with the American critic Harold Rosenberg’s definition of action painting coined in 1952 that privileged the heroic artist’s exploration of personal identity, emotional experience and existential choice. In a lecture he gave at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in October 1956, Davie set out to describe his rejection of conscious decision-making and the immediacy he thought vital to his art expressed in the form of enigmatic signs. ‘What I am trying to get at is at best expressed by the idea of pure intuition… to arouse the faculty of direct knowledge by intuition; and what we feel by intuition requires symbols or pointers more than ideas for its proper expression… these pointers are of necessity enigmatic and non-rational. Intellectual interpretation of them brings us no nearer to their meaning.’

Alan Davie

Sacrifice (1956)

Tate

During the later 1950s and 60s Davie’s work gained critical and commercial success. In 1958 London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery hosted his first major retrospective exhibition, an important milestone which David Hockney cites as having an impact on his own early explorations of abstract and figurative painting. Two years earlier, Davie had had his first exhibition in the United States at the Catherine Viviano Gallery, New York. During his visit to the city, he became the only British painter after William Scott to meet many of the leading American abstract expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell and Mark Rothko. For Davie these artists captured the dynamic energy needed to stimulate a new growth in painting but, in terms of his own work, the next stage was to refine his process and subject matter. That year Davie made seven paintings titled Image of the Fish God. It was the first time he worked on a theme in series. It was made in tandem with drawing on up to 20 sheets of paper placed on the floor with black oil or gouache, marking each one sequentially with single marks and signs so the series developed as a unit. As with most of Davie’s titles Image of the Fish God 1956 (fig.6) is a poetic interpretation, the fish having Christian references. The presence of sexual imagery also encountered in his work from this period can be seen in the right-angled figure ending in two points that re-appear in subsequent paintings.

Alan Davie

Image of the Fish God (1956)

Tate

Another important aspect of Davie’s practice at this time was gliding, an activity the artist took up in 1960 and shared on many occasions with his friend, artist Peter Lanyon. ‘I discovered that I could be a bird…’ he explained in 1963, ‘…How much more important than Art, just to be a bird.’12 The stimulation Davie derived from physical activity and the natural world reveals a correlation between his collaboration with the elements through the act of letting go and the intuitive revelations in painting he believed were a vital life process. Photographs from the 1960s show him perched in front of his beloved E-Type Jaguar which he used to tow his glider around the English countryside, while in aerial shots Davie is seen wheeling above the Cornish coast:

I did 22,000 hours gliding. It gave me an experience which was a confirmation of something I already knew through painting. The important thing for me is that one became part of the air. You have this minimal technology, just a joystick and foot pedals, and you may be at 16,000 feet – higher than the highest Alp – just using the air to stay up. The feeling that you had was of being a bird. Eventually, the wings seem to come out of your own shoulders and your intuition is in tune with the elements. You realise that the air is not an empty space, it’s a solid that bears you up. It’s a most incredible experience of the miraculous thing life is.13

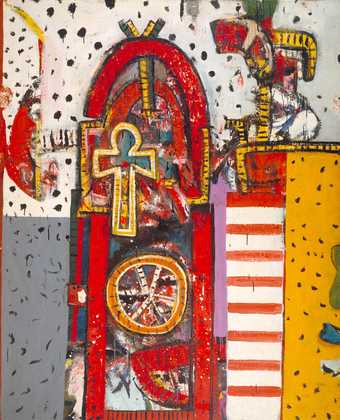

Alan Davie

Entrance for a Red Temple No. 1 (1960)

Tate

Davie’s paintings of the 1960s bear witness to the artist’s pursuits of fast cars, gliding, scuba diving and sailing that as powerful extensions of the body brought him closer to nature. Increasingly in his art, Davie responded to stimuli more systematically and conceptually, often in series of drawings and paintings in which calligraphic forms and archaic motifs begin to appear with greater clarity at the expense of gestural brushwork. Entrance for a RedTemple No. 1 1960 (fig 7) is suggestive of ancient art and architecture that for Davie had a powerful capacity to communicate directly. Its enigmatic wheel of life and ancient ankh symbol (the cross with a loop at the top) set against a series of arches and striped motifs reveal a fantastical world, a timeless object of meditation inviting the eye like the entrance to a place of worship. Taking three years to complete, it went through a series of transformations, the early stages of which are captured in the film of Davie working in his studio shot by his wife Bili. This Super-8 film footage opens with Davie making preparations for several canvases laid flat on the studio floor. Stripped to the waist, he moves between them, crossing the stretcher and crouching in the centre of the canvases to block out areas of paint in vibrant colours, adding circles, arcs and arbitrary words before blending with his hands. At one stage, Davie can even be seen sweeping the studio floor with a dustpan and brush before emptying the contents onto the surface of his pictures, adding an unexpected textural dynamic. As eyewitness to Davie’s inner world, the film reveals an artist revelling in his virility, confidence and prowess with paint.

Davie’s next screen appearance was the inclusion of several of his paintings in the British film Blow Up, 1966. Its director, Michelangelo Antonioni, shared Davie’s commitment to creative intuition and improvisation and visited his studio during the preparation of the film. Seen as an icon of swinging London and starring David Hemmings as a fashion photographer, the film’s plot involves Hemmings’s character, Thomas, discovering that he may have witnessed a murder while on a photographic shoot in a London park and unwittingly taken photographs of the incident. The film’s questioning of perception and reality (the photographer thinks he can penetrate the surface of his photographs to unlock the mystery of the murder) is undermined by the spirit of Davie’s paintings that serve as a reminder of the futility of searching for rational truth in images. As Antonioni reflected, ‘We know that underneath the displayed image there is another one more faithful to reality, and underneath this second there is a third one, and a fourth under the previous one. All the way to the true image of that reality – absolute, mysterious – that nobody will see. Or all the way to the dissolution of any reality.’14

Much of Davie’s work has been discussed in the context of psychoanalysis, and his method stems from the Jungian rather than Freudian view of the unconscious that played a dominant role in surrealist thought. Influenced by Jung’s ideas about symbols as indicating a collective memory from a deep reservoir of shared experience, Davie warned against the attribution of fixed meaning to his symbols. As he explained, ‘Certain images reappear in my work – they become obsessive symbols but are never used consciously for any purpose or conveyance of special meaning. Mainly, I feel, many of them are primordial symbols which have many and varying meanings at different times but unknown to mankind.’ For critic Robert Melville, Davie’s shapeless gestures become explicit signs as soon as they appear on the canvas, their pictorial treatment and particular kind of illusionism giving them an emotional weight. As a result, ‘Circles turn into wheels or breasts, sweeping curves tend to become worms or snakes, “S” signs rear for striking or dip to avoid attack, “C” signs snarl… These important and unusual events have the nature of remote commentaries on the more orgiastic aspects of human behaviour, for the pictorial treatment of the signs gives them the potency of compulsive substitutions.’15

During the 1960s while British artists Robyn Denny, Richard Smith and William Green were renegotiating action painting and moving towards post-painterly abstraction, Davie’s art shifted towards a postmodern revival of figuration, narrative and myth. His images took on a new direction after 1971 when the artist began spending part of each year living and working on the Caribbean island of St Lucia. The move brought about a fresh dialogue with art of ancient cultures, enabling the artist to tap into cosmologies less understood in the western world. During the following twelve years, Davie worked in cycles of 12 months, passing alternate six-month periods at his studio in St Lucia where each new body of work originated. Here, Davie produced prolific series of automatic drawings and gouaches, their most powerful and magic imagery finding their way into oil paintings executed later at the artist’s Hertfordshire and Cornwall studios. As a result, in paintings such as Fairy Tree No. 5 1971 (fig.8) Davie’s loose brushwork disappears altogether, the composition and handling more formally controlled and structured. One of eight versions around the subject, this painting features a willowy tree-like form from which the series takes its name, a free mass of watercolour that ran off the bottom of a sheet of paper having suggested some kind of magic tree. Laid flat against the picture plane, the crescent moon, serpent and fan-like mask are recurring motifs in Davie’s paradox of improvisatory figuration in which elements of one theme continue with those of another in a process of pictorial cross-fertilisation.

Alan Davie

Fairy Tree No. 5 (1971)

Tate

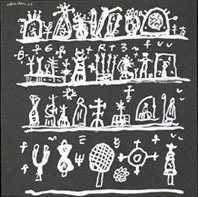

It may come as no surprise to learn that Davie had an impressive collection of African, North-American Indian and Oceanic art that has on several occasions been exhibited alongside his paintings. Jainism, which believes the universe has always existed and is governed by cosmic laws and energy processes, became a particular obsession after Davie encountered Jainist diagrams in a New York gallery. Another was a group of ancient Carib Indian petroglyphs that Davie tracked down on a trek through the Venezuelan jungle. He discovered that these forms from 3000 BC are found in other cultures and delighted in the fact that, as in his images that exist in visual and non-verbal forms, no one has been able to explain their meaning. Village Myths is the title attributed to a group of 30 gouaches and 16 oil paintings produced between 1982 and 1983 that manifest the artist’s thinking about a place where all religions and all distant cultures can co-exist. With its elaborately-wrought setting with decorative buildings, a mystical horned creature, skull, serpent and feathered headdress accompanied by inexplicable words like ‘DASHAMAHAVIDYA’, Village Myths No. 36 1983 (fig.9) appropriates motifs and symbols from a variety of cultures for a modern civilisation lacking its own village myths. When asked about a possible link between the clear and explicit way the imagery is presented in the painting, and the way one sees very clearly in dreams, Davie concluded that his ‘pictures are not like dreams, they are dreams’.

Alan Davie

Village Myths No. 36 (1983)

Tate

The mural Davie was invited to make in 1987 for French artist Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden in Garavicchio, Tuscany, brings together many aspects of his varied practice. The garden features a number of enormous sculpted figures and Davie painted the interior of Il Mago (‘the magician’), the head that visitors enter and climb up inside. Over a period of two weeks, he developed the mural’s imagery as a cornucopia of pictograms, signs and words centred on a large ankh symbol. Punctuated with pieces of mirrored glass that distort spatial perceptions, the result is an immersive experience of Davie’s magical visual world that explores the creative process and the meaning and purpose of art in the artist’s unique way. Throughout his career, Davie believed that art should flow out of the totality of life. The content and appearance of his paintings may have changed over the years but, as the works on display at Tate Britain suggest, Davie’s practice was underpinned by his idea that ‘Painting is a continuous process which has no beginning or end. There never really is a point in time when painting is NOT.’16