For many of us, memories of museum visits call to mind not only the artworks we encountered, but also the surrounding materials that helped us to learn about them. These framing devices take on many forms – exhibition brochures, wall labels, audio guides, or educator-led tours – but all serve the purpose of mediating and facilitating a visitor’s engagement with artworks on view.

Audio description is one form of mediation that traditionally is associated with museum access programming. Conceived as a resource for individuals who are blind or partially sighted, audio description uses precise language to describe visual imagery, with the aim of translating the experience of looking at an artwork into words. These descriptions can be conveyed live with a describer speaking to a group, or they can circulate via audio guides or online platforms as sound files or video voiceovers. Beyond this originating aim, audio descriptions have broad value for all audiences: the narrations call attention to material aspects that people might not notice on their own, detail sometimes unfamiliar artistic techniques, and offer contextualising historical or cultural information. When audio descriptions are shared online, they serve the additional function of introducing individuals to specific artworks they might not be able to see in person.

As with any interpretive text, audio descriptions are written by an institution’s staff members or other contractors. While these resources aim to make artworks accessible across levels of sight, their content reflects the author’s choices of how to prioritise visual information and balance this with complementary commentary. To recognise the author’s role in drafting these texts is to confront the spectre of objectivity – the notion that a well-crafted description should come as close as possible to offering a one-to-one rendering of the factual aspects of an artwork’s appearance. Many organisations that offer guidelines for scripting encourage describers to strive for such neutrality. However, a growing body of writing by scholars and practitioners such as Georgina Kleege, Georgia Krantz, and Thomas Reid calls attention to the inherently subjective nature of the practice. This broadened understanding takes into consideration the ways sight is bound up with lived experience: we each process visual information through the lens of our own references, associations, and biases. Further, as artists Bojana Coklyat and Shannon Finnegan highlight in their project Alt Text as Poetry, the process of constructing a text-based description of an artwork is an act of translation that requires the describer/translator to make ‘creative decisions’ about how to reconcile gaps in equivalences between images and words.

When acknowledged transparently, these factors are not limitations to the efficacy of audio descriptions but, rather, sources of potential. Naming the ways that individual viewpoints shape such scripts opens space to regard them as just one interpretative resource alongside the range of others institutions provide. Each instance of interpretation evinces various influences, from the curator or educator’s personal research interests to the institutional investments in certain cultural narratives. Put another way, none of these materials are neutral: each is a case study of how identity and institutional power dynamics come to bear on the mediation of artworks.

A new suite of audio description films produced by Tate as part of the Terra Foundation For American Art Series underscores this point by showcasing artworks that themselves engage with themes of power and identity: Etel Adnan’s Untitled 1970, Glenn Ligon’s Condition Report 2000, and Sharon Hayes’s Everything Else Has Failed! Don't You Think It’s Time for Love? 2007. To further align the form and content of these resources, Tate’s Public Programmes team invited staff members from the BAME, LGBTQI+ and disAbility communities to script and record the descriptions. They then asked me to write about the films in relation to the broader field of audio description, adding a level of reflexivity to the series by creating occasion to treat the resources as subjects of study in their own right. The team’s prompt calls for an approach to interpretation that moves away from the tradition of discussing artworks as autonomous entities and instead recognises the ways that our encounters with objects are entangled with and informed by their institutional mediation. In what follows, I have taken up this invitation to think about how a reflection on the very act of describing might add new layers to our appreciation of the artworks described.

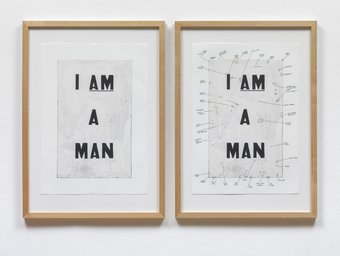

Glenn Ligon, Condition Report 2000

Glenn Ligon

Condition Report

(2000)

Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 2007

Both prints in Glenn Ligon’s diptych Condition Report centre on bold text that initially reads as an objective statement about an unnamed subject: ‘I AM A MAN’. The audio description of this work begins by detailing in a similarly factual manner the artwork’s formal and compositional properties. The descriptive inventorying evokes the technique used to produce the titular document – a type of record central to the field of artwork conservation that tracks an object’s precise material qualities and its changes over time.

As the film progresses, the describer John Hughes introduces information that reveals how Ligon’s reference to a condition report extends from an examination of the supposed neutrality of empirical information. We learn that the artwork refers to historical source material at two levels of remove: a protest sign that Black sanitation workers held during Civil Rights marches in 1968, which Ligon first rendered in 1988 as a painting on canvas titled Untitled (I Am a Man) and then revisited in Condition Report as print reproductions of the painting. In their original context, the signs were tools for protesters to call attention to how the workplace abuses they experienced were indicative of a wider societal devaluing of Black life. The seemingly straightforward message – a declaration of the workers’ existence – pointed to the ways that systemic racism negates basic truths about humanity.

With Untitled (I Am a Man), Ligon raised questions about the extent to which the statement’s fraught resonance would shift when it appeared two decades later as a descriptor without a subject. After another twelve years, Ligon furthered his exploration, this time inviting a third party to respond to the protest sign. Inspired by his own observation of cracks and other defects on the painting’s surface, the artist asked conservator Michael Duffy to annotate one of two print reproductions of Untitled (I Am a Man) with comments on the painting’s condition. In this way, the artist shifts the relationship between the central words and their reference: no longer a statement describing a person’s identity, the sentence becomes an object to be studied for its material traits. Duffy’s markings seem to introduce a hierarchy of information, with the practical implications of the professional, conservational commentary eclipsing the original statement’s descriptive significance. Yet by positioning the report alongside an unmarked print, Ligon prompts the viewer to consider how both are mediations of the original reference, filtered through different systems of representation and description.

Following the work’s logic, Tate’s audio description itself becomes an additional case study in translating empirical data across visual and textual forms. Everything from the order in which Hughes conveys elements of the work’s appearance to his choices about when to introduce contextual information has an impact on a viewer or listener’s impression of Condition Report. Rather than regarding the film as a standalone portrayal of the work’s physical form, it is instructive to align this resource with the summary provided on the Tate’s website: together, these two texts could be seen to function like a diptych in much the same manner as the two prints in Ligon’s work.

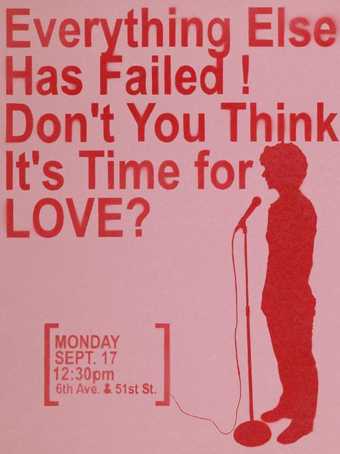

Sharon Hayes, Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? 2007

Sharon Hayes

Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time For Love?

(2007)

Tate

The audio description of Sharon Hayes’s installation Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? opens with an allusion to dialogue. The describer Chris Timms tells us that a row of five framed posters hangs on a wall across from the same number of speakers on stands, suggesting that these objects appear to be interlocutors poised for conversation. With this observation, the film highlights one of the work’s salient themes – the potential for speech to transmit across parties – while also alluding to the form of direct address that the practice of audio description implies between speaker and listener.

Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? marks a space of communication that is itself an evocation of a previous exchange. The narration indicates that the speakers broadcast recordings of a series of five performances that occurred in 2007 in New York City, during which Hayes addressed a crowd of both intentional audience members and passersby. In the first instance, as Hayes read a series of love letters directed to ‘my dear lover’ or ‘my sweet lover’, those listening could imagine the unidentified ‘you’ as a proxy for themselves as they absorbed the words in real time and in the artist’s presence. The installation filters this mode of speech across time: the inclusion of the posters naming the title, date and location of the original performance grounds the recorded voice in a specific historical moment, even as it resounds in the present space of the gallery. The open-ended ‘you’ remains, but listeners know that they are privy to this acknowledgement only as a secondary audience.

The mediation of the audio description shifts the direction of Hayes’s address again, adding further distance between her, her unnamed subject, and the listener. Here, another voice enters the conversation as the describer, Timms, relays the experience of the installation to the listener. Through this new correspondence, the exchange is no longer between the artist and an individual subject of ‘you’, but instead between Timms and the collective body of ‘we’ who comes together to reflect on the artwork. As in Hayes’s piece, the transmission between the speaker and the listening body in the film is unidirectional, and the possibility for connection across these positions is indefinite. In the case of Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love?, the lack of reciprocity across parties might be understood as pointing toward the breakdowns of communication within society more broadly. Alternatively, in the audio description, the one-way nature of dialogue serves a generative function as a partial corrective to access barriers, bridging the gap between Hayes’s artwork and audiences who otherwise wouldn’t be able to come into contact with it.

Etel Adnan, Untitled 1970

Etel Adnan

Untitled

(1970)

Tate

In contrast to the single voice present in Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love?, Etel Adnan’s leporello book Untitled 1970 both visualises and sets into motion a series of exchanges between several collaborators. As detailed in the audio description, the book contains a transcribed version of the poem ‘Assassination Raga’, written by Adnan’s friend the late American poet and painter Lawrence Ferlinghetti. The lines of the poem appear across the pages in black ink, merging with washes of coloured ink, large hieroglyphic signs, and the word ‘Allah’ in Arabic. The describer, Cina Aissa, notes that through Adnan’s compositional choices, ‘the poem merges into a painting’, and that by ‘integrating Ferlinghetti’s words into her piece, [she] turns Untitled into a powerful collaboration’. The artist’s process of translating her friend’s work into a new medium sets the model for the transmutation that occurs in the audio description. While Adnan transformed the poem’s text into a visual form, Aissa molds vivid language to convey the composite effect of the poet’s words and artist’s imagery.

Over thirty years after completing the piece, Adnan added another layer of interchange to Untitled, this time by gifting the book to a second collaborator, the Italian art historian and cultural activist Toni Maraini. The artist and Maraini had been in dialogue since 1978. In that time, Maraini had translated many of Adnan’s short stories and poems, and had written about her art. There is a symmetry, then, in Adnan passing on her expressive translation of Ferlinghetti’s poem to someone who had engaged with her own work in a similar way. Carrying this process forward, the audio description brings Aissa’s perspective into the accruing chain of responses across forms.

***

Each in their own way, the describers of Condition Report, Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love and Untitled have crafted interpretive resources that mirror and build on the artist’s lines of inquiry. The resulting films are creative articulations that, like the artworks they showcase, grapple with how to parse the subjectivity of received information, communicate across subject positions and translate material into different forms. By extension, these audio descriptions can inspire each of us to take up these questions – and to imagine our own responses entering the network of interpretations that exists around artworks in the space between institutionally produced materials.

Alison Burstein is a curator at The Kitchen in New York. Her research primarily explores the ways that institutional structures shape the production, presentation and reception of artworks.

See below for links to the audio description films.