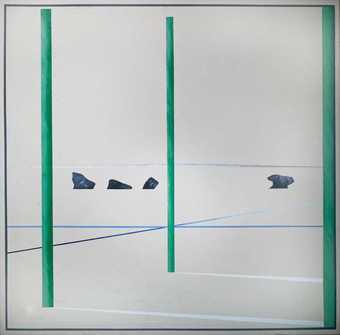

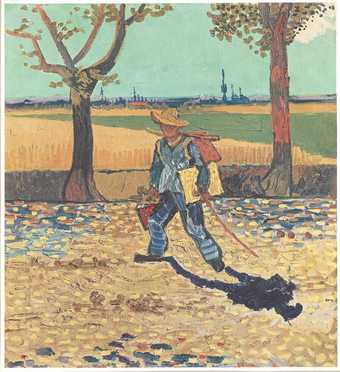

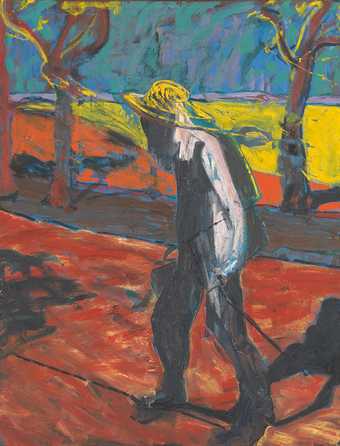

Vincent van Gogh, The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, 1888, oil paint on canvas, 48 x 44 cm (destroyed)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

It begins with Van Gogh’s Painter on the Road to Tarascon 1888, which was destroyed by the Allied bombing of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum at Magdeburg, or with Francis Bacon’s convulsive reconfigurations of that work. Like Bacon, I had been uncomfortably schooled in Cheltenham, a town of spooks and returned colonials for which neither of us had much sympathy. But the teaching was, in some respects, surprisingly liberal: I heard about Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, Picasso and Braque, Wyndham Lewis and vorticism. We were told about Vincent van Gogh’s (1853–1890) time among the potato pickers and his days in Paris, but little or nothing about his work as an art dealer in imperial London. And nothing at all about his passion for English literature: Charles Dickens, George Eliot, John Keats and Thomas Carlyle. The basic trajectory was always conflict and struggle in the dark north and that final, brief liberation of Arles, the overwhelming intensity of vision and the crows of madness, as the starry heavens seethe and boil.

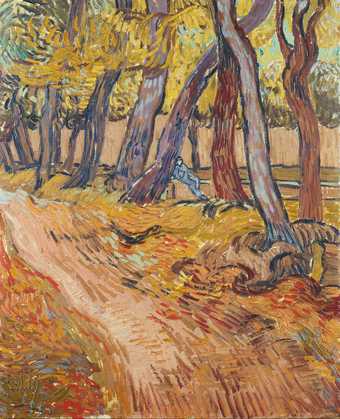

In 1889, the year of his removal to the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence when the rubbing away of the thin mantle between individual and universal consciousness was absolute, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo about experiencing ‘that glimpse into a superhuman infinitude ... that you come upon in many places in Shakespeare’. English literature, with its sentiment and confident address, helped to shape the artist’s mature vision. To the end, Van Gogh pictured himself as an overburdened working man halted between trees on the pilgrim’s road. The motif derived from George Boughton’s painting, Godspeed! Pilgrims Setting Out for Canterbury. Here too was the inspiration for Vincent’s first sermon at Kew Road Methodist church: life as pilgrimage. It is known that Van Gogh visited the Royal Academy exhibition in 1874 at which Godspeed! was hung.

George Henry Boughton, Godspeed! Pilgrims Setting Out for Canterbury 1874, oil paint on canvas, 122 x 184 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

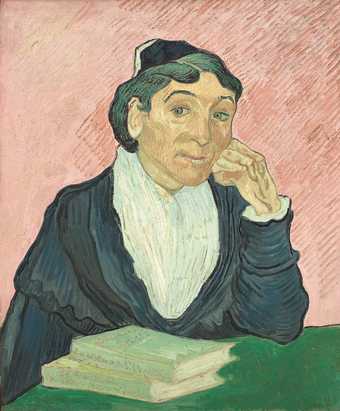

Vincent van Gogh, The Arlesienne 1890, oil paint on canvas, 65 x 54 cm

Collection Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, photo: João Musa

In a portrait painted at Saint-Rémy, the Christmas Books of Dickens are placed beside Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the table in front of a faintly smiling and duplicitous Marie Ginoux, the subject of The Arlesienne 1890. But the paper-covered volumes do not belong to Madame Ginoux. They are realised physical objects carrying Van Gogh back to the innocence of his London days. Vincent had his top hat, but the uniform of international commerce pinched. The shadowy other, that nagging internal voice, had not yet declared itself. The temporary immigrant – no papers or passport required – sold pictures and collected prints, but he did not paint. He sketched in the margin of letters: topographic information, churches, schools and lodging houses. He copied and worked variants on illustrations he admired in the magazines of the day. Returning to his lodgings, he paused. ‘When I was in London, how often I would stand on the Thames Embankment and draw as I made my way home from Southampton Street in the evening, and it looked terrible.’

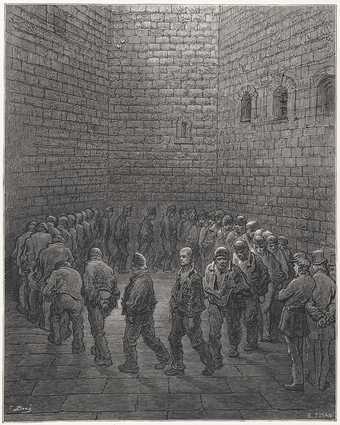

London: A Pilgrimage, a record of walks undertaken by the journalist Blanchard Jerrold and his illustrator, Gustave Doré, was published in 1872. Vincent gathered the prints and pinned them to the walls of his rooms, wherever his migrations carried him. It is a night city, a Stygian narrative. The river is poverty and suicide, pale lamps in the fog. London is bursting at its soiled seams. It is all dust and foul water. The drowned return to life and riches are excavated from filth: the city of Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend.

Gustave Doré's engraving Newgate - Exercise Yard, a plate from London: A Pilgrimage, published in 1872

In good standing after his apprenticeship as a dealer at Adolphe Goupil’s gallery in The Hague, Vincent was transferred to the Covent Garden outlet on Southampton Street in May 1873. That other hobnailed visionary and sun worshipper, Arthur Rimbaud, had returned to London to rejoin Paul Verlaine in the same year. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire, friend and promoter of early modernist painters, arrived at 75 Landor Road – just a few streets from Vincent’s rooms at 87 Hackford Road – in May 1904, hoping to persuade Annie Playden to marry him. But she left for America and never returned.

Vincent’s own failed courtship of Eugenie Loyer, daughter of his landlady, Ursula, devastated him. Eugenie, who may have tolerated or barely noticed his interest, was already engaged when he made his awkward approach. In London, it is thought, Vincent purchased his first experience with a prostitute. He wrote to Theo about his ‘love for those women who are so damned and condemned and despised by the clergymen from the pulpit’. In later times, on behalf of his Dickensian employers, he would collect unpaid school fees in Whitechapel.

Visiting Tate Britain in August 2018 to hear something about the complexity of Vincent’s engagement with British art and literature, I remembered 1962 and my repeated walks across the river from Brixton, where I was a film student, in order to grapple with the major Bacon show at the Tate on Millbank. It hit me with the force of a magnetic storm. I wanted to look again at Bacon’s Homage to Van Gogh series, and, in particular, his version of Painter on the Road to Tarascon. The rucksack, the melting, tarry shadows: this moment, like a freeze frame smoking in the projector, was the motif that defined my future relationship with London.

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait of Van Gogh IV 1957, oil paint on canvas, 152.4 x 116.8 cm

© Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2018, photo: Tate

But if Bacon, and Harold Gilman – who was avid for the hurt of colour in a period dominated by Walter Sickert’s chewy tobacco browns – demonstrate the pull of Van Gogh on future generations, then that energy flowed both ways. The heat of the South, those thick gestural strokes, are recoverable from the work of Spencer Gore, Matthew Smith and David Bomberg. But the original cold British exile, with his drawings in the corners of letters to Theo, is still largely untapped.

The address of Van Gogh’s first London perch has not been identified. There were German lodgers and parrots. The move to Hackford Road brought him within walking distance – 45 minutes it is said – of his place of business in Southampton Street. Attempting to retrace his footsteps after my meeting at Tate Britain I can only marvel at the length of his stride. It would force a casual pedestrian into something close to a jog to accomplish the distance in the time allowed. Vincent’s morning commute, the movement between modest domesticity and the never-satisfied engines of commerce so nicely calibrated by Dickens, offered up visions of working London’s ‘Monday-morning-like sobriety and studied simplicity’.

Sometimes in the company of his sister Anna, who was training to be a teacher, Vincent took in the orthodox sights: St Paul’s, the Dulwich Picture Gallery and Hampton Court. Parks and gardens had a special appeal, often with the furtive pull of eavesdropping on those lovers in a conspiratorial quest for privacy against the witness of the streets. This London stayed with the painter: ‘Hampton Court with its avenues of linden trees full of rookeries’.

Vincent van Gogh, Trunk of an Old Yew Tree, Arles: October 1888 1888, oil paint on canvas, 91 x 71 cm

Private collection, photo: Tom Powel Imaging 2018

The address of 87 Hackford Road is now a regeneration site – boxed and posted with optimistic predictions of the good times to come. Van Gogh’s blue plaque is a trompe l’oeil reproduction on the protective shell. Close at hand is a little memorial park dressed with carved quotations. There are laminated notices telling us how Vincent was ‘enchanted by his walks in and around Stockwell’. Attached to a tree at the mouth of Van Gogh Walk is a notice offering a reward for a ‘Lost Bird’, a green parrot. In a tub on the tributary running towards Clapham Road is a gesture of hardy sunflowers.

So I began, unpremeditated, a series of walks through those odd, unreal, summer days while I attempted to connect Van Gogh’s English addresses. Surviving houses and chapels, in the end, feel less significant than the movement between them, when weather and light and random encounters effect an interweaving in the strands of time. Tate Britain both is and is not the panopticon prison of Millbank. The distance between Hackford Road and Southampton Street, or Isleworth and the City of London, doesn’t change, but everything else along the way does. Only in certain moments, catching breath, do we experience the illusion of understanding what Van Gogh felt and saw.

‘I used to pass Westminster Bridge every morning and every evening,’ Vincent wrote, ‘and know how it looks when the sun sets behind Westminster Abbey.’ The bridge has its barriers now, its security negotiations, before I reach unchanging Whitehall and a detour to the National Gallery, where Sunflowers 1888, painted for the Yellow House in Arles, has become a major marketing device. You can’t approach the picture for the blizzard of raised phones. The image is flattened, multiplied and miniaturised a thousand times.

Dispatched from the school on Twickenham Road in Isleworth to collect money due to his employer, Thomas Slade-Jones, in the City, Vincent tramped the Thames like Bradley Headstone, the pinched schoolmaster-stalker from Our Mutual Friend. ‘The suburbs of London have a peculiar charm, between little houses and gardens are open spots covered with grass and generally with a church or school or workhouse in the middle between the trees and shrubs.’ Van Gogh was struck, when he read John Forster’s Life of Dickens (1872), by how the great writer had meditated while on the move, hatching ‘serious plans’ as he headed out into the country.

Vincent van Gogh, Path in the garden of the asylum, November 1889 1889, oil paint on canvas, 61.4 x 50.4 cm

Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

In Isleworth, under the Heathrow flight path, the library is closed, but a useful leaflet on ‘10 Steps to an Active You’ explains how ‘brisk walking can reduce your risk of long-term health conditions like heart disease and cancer’. The blue plaque on the red-brick house across the road offers ‘flexible terms’ for ‘serviced offices’ and boasts that ‘Vincent van Gogh, the famous painter, lived here in 1876’. But of course he didn’t: Vincent was obscure, isolated, estranged – and he wasn’t yet a painter.

Syon Park grants the tolerated passerine a glimpse of long, shaded avenues, figures retreating or advancing, ghosts from earlier times. Vincent was captivated by that motif, poplars framing a road at sunset, shadow bars trapping solitary walkers. Beside the Thames, at Strand on the Green, I photographed the beautifully kept ‘Dutch House’. A notice announced classes in St Michael’s Church at £90 for three sessions: ‘All about Drawing – for adults.’

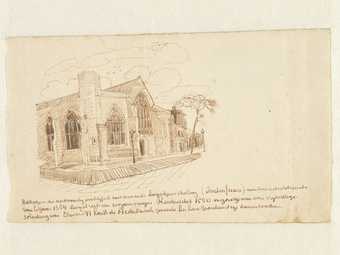

Drawing by Van Gogh of Austin Friars, a Dutch church in the City of London, possibly enclosed in a letter to his sister Anna, July 1873 – May 1874

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Not knowing the precise route the novice preacher took, I came away from the Thames at Hammersmith Bridge and cut across the chain of Royal Parks. And I made my own destination in the City, the Austin Friars church that Vincent is known to have sketched on one of his excursions from Isleworth. ‘The Dutch Reformed Parish has held gatherings here’, he wrote on his drawing. Accessible still by a white-tiled passage with notices for ‘Stock & Share Brokers’, the church is dwarfed by indifferent and unrelated towers.

It was by accident that I found myself on the shared road of Van Gogh’s longest, most driven English walk. We coincided at Canterbury: he had come from his unpaid employment at the school in Royal Road, Ramsgate and I was tracking Watling Street from Dover to London. Buffeted by traffic on the unforgiving stretch between Faversham and Gillingham, I envied Vincent the ride he caught on a cart, leaving it only when the carrier settled in a public house.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees 1889, oil paint on canvas, 51 x 65.2 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, photo: Antonia Reeve

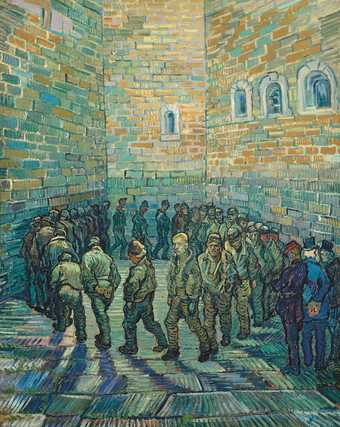

No sooner in Lewisham than the restless visionary was off again, rising before first light to tramp to Welwyn where his sister was employed as a teacher. I followed him on the day that rain returned after those parched months. Passing the Poor Clare Monastery beyond High Barnet I thought of the other inextinguishable figure of the Great North Road: the poet John Clare. Poor John. Now drenched, ditched by an endless stream of commuters, reps and white vans dodging in and out of the motorway system, I empathised with Clare’s delirious account of his ‘Journey Out of Essex’, the four-day trudge from Epping Forest to the new cottage in Northborough, where he would be ‘homeless at home’. Clare’s urgent report reads like a one-breath confession, spontaneous and uncensored. Van Gogh’s London letters can be set beside Clare’s as announcing the coming era of ‘mad walkers’, fugue walkers and deep topographers. Looking at Prisoners Exercising (after Doré), painted in Saint-Rémy in 1890, I think of Clare in the Northampton asylum and the despairing abdication of the sonnet, ‘I am’: ‘And plod upon the earth, as dull and void: / Earth’s prison chilled my body with its dram / Of dullness’.

Drawing on the Doré print from London: A Pilgrimage, Van Gogh has one man turn to confront us, his accusers. Perhaps this is indeed a self-portrait: the pre-traumatic face of the faceless man from the road to Tarascon. The position of the troubled walker’s stride is identical in both paintings. The pilgrim is doomed to tramp on, as if caught in the circuit of the stars, only to arrive back where he started.

Vincent van Gogh, Prisoners Exercising (after Doré) 1890, oil paint on canvas, 80 x 64 cm

State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow/Scala, Florence

The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain, 27 March – 11 August, curated by Carol Jacobi, Curator British Art 1850–1915, Tate and Chris Stephens, Director, Holburne Museum, Bath with van Gogh specialist Martin Bailey and Hattie Spires, Assistant Curator Modern British Art, Tate. The exhibition is part of The EY Tate Arts Partnership, with additional support from the Van Gogh Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Members.

Iain Sinclair is a writer and filmmaker, and a compulsive London walker. His latest book, Living with Buildings, is published by Wellcome Collection and road tests the thesis that staying on the move delays mortality.