Patrick Heron at Eagles Nest, photographed by Delia Heron, c.1965

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

Katharine Heron remembers her father's love of architecture

On a recent visit to Pittsburgh, my husband Julian and I visited Kentuck Knob, the house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and owned by Peter and Hayat Palumbo – now open to the public. We had visited it together with my father, Patrick, some 25 years ago, staying overnight, and had loved it. On this trip we noticed that there, on display in a small sketchbook, was a drawing of another iconic house – the Farnsworth House designed by Mies van der Rohe. The drawing was instantly recognisable as having been drawn by Patrick when he stayed at Farnsworth with Peter. It reminded me of how much he had loved modern architecture and architects.

Patrick Heron's sketch of the Farnsworth House designed by Mies van der Rohe, drawn while staying there with Peter Palumbo in the 1980s

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018, photo: Cheri Wade

Patrick probably had as many architect friends as artist ones. Two of his best friends at school became architects, and as a child he had clearly idolised Wells Coates who had been commissioned by Patrick’s father, Tom, to design a number of Crysede and Cresta Silks shops, and, later, the show area for the new Cresta factory in Welwyn Garden City. One Christmas, when the family were living in St Ives, Wells had given the young Patrick a Meccano set, and together they made a construction.

The dreadful interruption of the Second World War began when he was in his teens, but by its end he had become a young man, married and eager to catch up on time lost in his career. His great friend Hugh Adams had died, but he renewed his architect friendship with Fello Atkinson and made a new and lasting friend in Trevor Dannatt. Architects for the Festival of Britain commissioned artists to make new works, and from one such commission Patrick painted Christmas Eve : 1951 1951. In 1957, Trevor commissioned Patrick to make Horizontal Stripe Painting : November 1957 – January 1958 1957–8 (now in Tate’s collection) for the new offices he was designing for publishers Lund Humphries. Both paintings were the largest he had painted and made specifically for an architectural context.

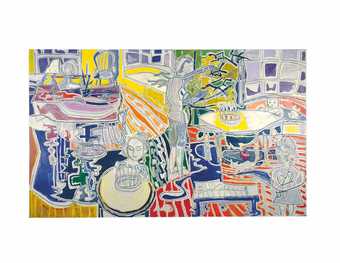

Patrick Heron, Christmas Eve : 1951, oil paint on canvas, 182.9 x 304.8 cm

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018, courtesy The Frank Cohen Collection

Committed to both conservation and new design, he wrote about architecture at intervals throughout his life – Architect’s Yearbook in 1949 and 1953, The Changing Forms of Art in 1953, and in Architectural Review for a piece on the Lloyds’ building designed by Richard Rogers. On a visit to Paris at some point during the end of the 1940s or early 1950s he met Le Corbusier, who was very interested in his surname, saying: ‘In French, it’s the name of a bird’, to which Patrick replied, ‘It’s the same bird in English ’. Patrick was a brilliant storyteller and mimic.

In later years, he served as a Trustee of the Tate Gallery with Richard Rogers. They had much in common, including their brilliantly coloured shirts, and together they visited Russia in an attempt to persuade the museum to make major loans of Matisse paintings to Tate. We would visit Creek Vean in Cornwall, the house Richard designed (as part of Team 4) for Marcus and Rene Brumwell.

Creek Vean in Feock, Cornwall, the house designed by Team 4 for Marcus and Rene Brumwell in 1963–6, which Heron visited regularly with his family

Photo: Richard Einzig - Arcaid

My father would take me on countless trips to look at buildings both old and new. In 1965 he drove me to my interview to study architecture at the Architectural Association in London, on the way pointing out the early construction works for the Centre Point building. We talked about the building and, luckily, it came up in the interview.

Patrick enthused me with his love of architecture and, I suppose, also taught me to draw. He was quite at ease with 2D representations of space in plans and elevations, which he could draw accurately himself, not to mention isometrics. Looking at these and other drawings he made, I recognise versions of them in many of his paintings, in the abstracted arrangements on a flat surface – whether as a representation of space, the drawing within a figurative painting, or in his later hard-edge coloured grounds.

Patrick had an experiential spatial approach to paintings. I have a vivid memory of going to Paris with him and my mother, Delia, in 1970 to see the centennial exhibition of Matisse at the Grand Palais. Here were the rarely seen (and never before by Patrick) great paintings collected by Sergei Chtchoukine in Russia – La Danse 1909 and La Musique 1910 – each measuring 2.6 metres in height and 3.91 in length. Patrick walked up and down the space before them, his figure close enough to their surfaces to paint them himself, immersed in their majestic size and absorbed by their colour.

Katharine Heron is Professor of Architecture, and recent Head of the Department of Architecture, at the University of Westminster. She is the founder and director of Ambika P3, London.

Susanna Heron responds to her father's work through four images from her personal collection

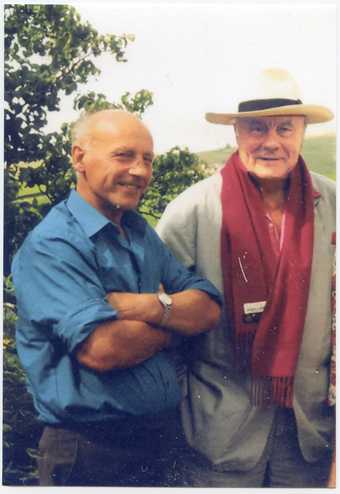

In the garden at Eagles Nest, May 2017

© Susanna Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

Patrick liked looking at things: the light on the sea, the sun setting over the horizon, the garden at Eagles Nest, white walls, the colour in his paintings, a bunch of violets, a rock, a jug, a fox. When I first hung Patrick’s large paintings in my house in London, I was struck by the change to the light in the room. It was as though the light reflecting from the sea at Eagles Nest was regenerated by light emanating from the paintings themselves.

Detail of 26 – 28 January : 1998

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018, photo © Susanna Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

Words were important to Patrick. His paintings have descriptive titles. They describe what is in the painting, but selectively, as in titles such as Still Life with Black Bananas : 1948 and Complicated Reds, Five Discs : March 1965. Later paintings recorded the length of time it took for him to make them, and the time of year. 26 – 28 January : 1998 was painted in winter light – whiter, more spare, sharper. Like the paintings, these titles need no interpretation and mean nothing but themselves.

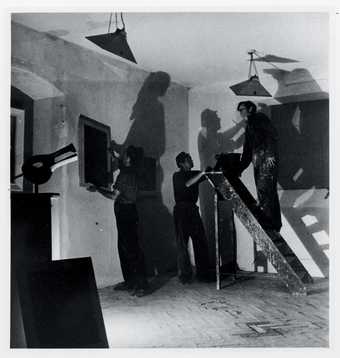

The finished painting 26 – 28 January : 1998 at Porthmeor Studios, St Ives, 1999

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018, photo © Susanna Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

Patrick’s later garden paintings appear daringly unfinished. The title 26 – 28 January : 1998 indicates that it was painted over three days, but he would have looked at it for longer, even for years, and this painting remained in his studio until he died. He wrote to me, ‘Is it finished?’ Every day it engaged his eye and his inner eye before he could conclude there was nothing to be added. It was an activity that engaged his mind and his eye.

Samples of red oil paint on paper painted by Patrick, c.1958

© The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018, photo © Susanna Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

I found this sample when I was examining Patrick’s stockpiled paint after he died. His stock of paint was a conservationist’s dream, dating back more than 50 years. Just as he liked the Latin names of plants, he loved the names of colours almost as much as colour itself. Was it Cadmium or Vermilion? Cadmium Deep or Cadmium Light? You can see his fingerprints where he has rubbed the paint to soften the edge. Unusually, you can see them in 26 – 28 January : 1998 too, although here it feels different – as though he got paint on his fingers by accident and tried it out, with no less certainty in the act. There is nothing like the real thing – the physical presence of paint, the scale, the real painting, seeing it now and in the moment.

Susanna Heron is an artist based in London. She is currently working on a large-scale stone relief for the western façade of a new Study Centre at St John’s College, Oxford, due for completion this year.

Patrick Heron, Tate St Ives, 19 May – 30 September. The exhibition tours to Turner Contemporary, Margate, 19 October – 6 January 2019.