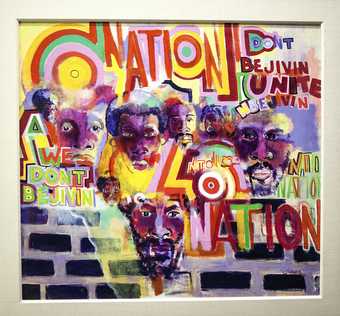

Gerald Williams, Nation Time 1969, acrylic paint on canvas, 121.9 × 142.2 cm

© Gerald Williams, courtesy Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All rights reserved

I grew up in Cabrini-Green, the Chicago public housing project based on the post-war modernist vision of the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, at 500 W Oak Street. We called the 19-storey building, with its white and red brick façade and rear concrete hallway ramps walled in by steel lattices, ‘Five Hundred’. In the 1990s the elders, including my grandfather Sammy, sat like sentinels, stylishly, on ‘the corner’, some sporting Afros in trench coats, drinking Colt 45 malt liquor. When I sat on that corner with my grandfather, they gossiped about the 1960s and Black Power, which produced in my mind a competing image of contemporary black life compared with the one I knew. A time before crack, when marches for civil rights turned into clenched fists and black lives mattered. When there was a real sense in Black America that by using our experience, the community could uplift itself and all of the nation. They talked about the time Martin Luther King Jr came to Chicago to fight poverty and was run out of town by ‘them white boys’. But it was aight because Fred Hampton, Bobby Seale and the Panthers didn’t take no shit. When they got drunk, they rapped feverishly, about the music – jazz and Chicago house – and what the activists and artists did ‘out south’.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power captures what the activists and artists did ‘out south’. It’s an exhibition that starts in 1963 and spans two decades of cultural activity by a decentralised group of individual Black artists and collectives working around the country who became associated with the Black Arts Movement (BAM), the aesthetic sister organisation of the Black Power Movement that took root after Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965. They used what poet Amiri Baraka, a key figure in BAM, called ‘Black art’ as a way to make various empowering statements about black identity and community. This was a new kind of socially engaged American art that established a willingness by Black artists to create imagery that matched the heft and contradiction of black nationalism by teasing out culturally specific representation of an American experience that started in slavery. Black artists came together and decided that black people no longer had to fit their desires, ideas and selves into white constructions. They needn’t imagine themselves as anything but themselves.

Carolyn Lawrence, Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free 1970s, acrylic paint on canvas, 124.5 × 129.5 cm

© Carolyn Mims Lawrence

Out south, Hoyt W. Fuller, the educator and author, founded the Organisation for Black American Culture (OBAC) in the mid-1960s. The multidisciplinary collective’s aim was to use, according to its manifesto, ‘cultural expression as a useful weapon in the struggle for black liberation’. In 1967, on 43rd Street and Langley Avenue in Chicago, OBAC unveiled the Wall of Respect, a mural depicting leading black radical politicians, writers, athletes, musicians and spiritual leaders. The ever-evolving work reflected the community’s changing understanding of itself. (Eugene ‘Eda’ Wade, one of the project’s principal artists, updated the wall to include the Black Power salute, signifying the shifting focus from the integrationist Civil Rights Movement to the separatist group.) Black heroes such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Muhammad Ali, Ornette Coleman, Malcolm X and Amiri Baraka were among those painted by lead muralist William Walker, artist Jeff Donaldson and OBAC members. Photographer Robert A. Sengstacke hung pictures of members of the community and collective on the wall. OBAC’s public art project focused on building the self-esteem of the local black community. The Wall of Respect inspired similar shrines around the country and became, according to Donaldson, ‘a national symbol of the heroic black struggle for liberation’.

Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary 1972, screenprint on paper, 86.4 × 67.3 cm

© Wadsworth Jarrell, photo: Tim Safranek

In 1968, after the completion of the mural, Donaldson, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Wadsworth Jarrell and Gerald Williams, members of OBAC’s Visual Workshop, formed a new artistic collective called the Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists (COBRA). A year later the group changed its name to the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA) to reflect the pan-Africanism sweeping the country that envisioned black liberation as a global struggle. AfriCOBRA continued OBAC’s call for a people’s art by producing positive images of black leaders and everyday people. Its members created art that reflected the revolutionary period that my grandfather and his friends reminisced about all those years later in Cabrini.

Williams’s Nation Time 1969, Carolyn Lawrence’s Uphold Your Men 1971 and Jarrell’s Revolutionary 1972 depicted leaders of the 1960s and 1970s paired with vernacular messages the group wanted to impress upon black people on the streets. Nation Time, for instance, features warm multicolour text that reads ‘DON’T BE JIVIN UNITE’ and Revolutionary is a groovy portrait of the Black Panther Angela Davis emerging from words such as ‘love’, ‘black’, ‘nation’, ‘full of shit’, ‘revolution’ and ‘beautiful’ painted in what Jones-Hogu called, in the 1973 Inaugurating AfriCOBRA: History, Philosophy and Aesthetics manifesto, ‘pure vivid colours of the sun and nature. Colours that shine on Black people’.

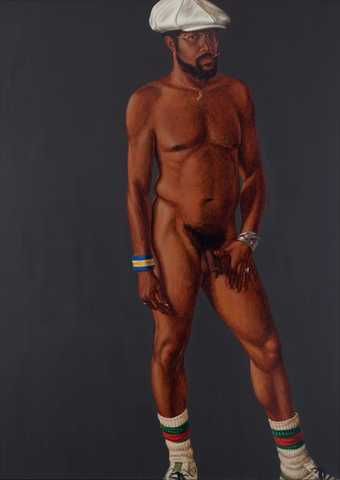

AfriCOBRA’s positive heroicised images, which functioned between abstraction and figuration, represented only one way artists incorporated the revolutionary themes of Black Power into their practices. Barkley L. Hendricks’s realistic and less essentialist self-portraits from the 1970s stood in contrast with AfriCOBRA’s art. He seemed less concerned with instructing black people to act than presenting raw, realistic and highly stylised reflections of black identity. His Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait) 1977, a full-frontal nude self-portrait, accessorised with a white hat, socks and shoes, shows the un-fashioning of his body. It displays a comfortableness that challenges America’s fantastical degrading presentation of black male sexuality. The work uses established Eurocentric notions of representation slyly to deconstruct gender and sexual stereotypes which furthered the freeing and empowerment of the black image.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait) 1977, oil and acrylic paint on canvas, 167.6 × 122.6 cm

© Barkley L. Hendricks, courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

AfriCOBRA artists made their paintings into poster prints and sold them at their exhibitions for $10 dollars. It reflected a strategy artists such as Faith Ringgold and Emory Douglas employed in the 1970s to get their art and the message of liberation into the streets and the hands of the people. AfriCOBRA’s vision of Black art functioned as a kind of agitprop against the popular self-referential modernism and negation of black experience in the museum and mainstream life. Its members’ humanistic portrayals of their subjects escaped the history of white America’s fantasies and fears that informed the erasure and racist depictions of black life in popular culture. Their art depicted the beauty, desire and humanness of their generation and black historical figures by using their circumstances to signify their subjects’ universality. It represented what Black Arts Movement theorist Larry Neal described as ‘a radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic’.

The art revealed interior black thought and life and imaged the complexity of men like my granddaddy, whose sitting on that corner was seen as being mired solely in narratives of black poverty. The fraternity of those on that Cabrini corner told a different story. I remember saying once: ‘All y’all do is talk about the old days.’ ‘Bucket head,’ my granddaddy said, taking in his surroundings, ‘we are more than this.’

Al Fennar, Rythmic Cigarettes, Greenwich Village, New York 1964, photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

© Albert Fennar

Antwaun Sargent is a writer living and working in New York City. His work has appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker and The Nation.