Digital image of a portrait of Marlow Moss, thought to have been taken by Stefan Nijhoff, A.K.A Stephen Storm

Private collection

Image courtesy of Florette Dijkstra

Marlow Moss (1889–1958) settled in Lamorna in the far west of Cornwall in 1941, some time after she had fled the outbreak of war in Europe. As a radical modernist artist, to say nothing of also being Jewish, a lesbian and dressing like a man, her escape via fishing boat to England had been somewhat urgent. However, she was familiar with Cornwall, and the light was not dissimilar to that of the southern Netherlands where she often spent time with her lifelong partner, the novelist A.H. Nijhoff.

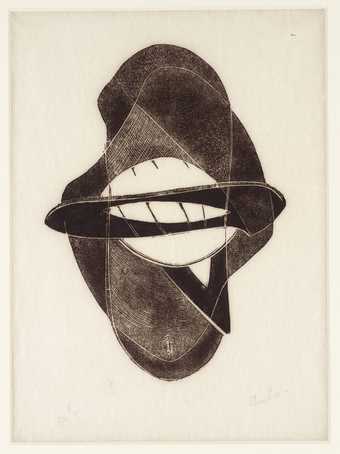

Moss must have cut a striking figure in the village, dressed in riding breeches and hunting jacket, with a silk cravat and her hair cut short. Local children, and even her own nieces on the occasion they had met, assumed she was a man – and an exotic one at that, given her foreign accent. Being an artist wasn’t unusual in Lamorna, but her austere geometric Constructivist artworks certainly were.

Marjorie Jewel Moss (Marlow was a name she adopted to suit her androgynous persona) was born to a middle-class family in London. She moved to Paris in 1927, attending the Académie Moderne at the relatively advanced age of 38 and being taught by Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. But it is the influence of Piet Mondrian that is most obvious in her art. She met ‘the master’ in 1929 and immediately co-opted his approach, limiting her palette to the primary colours and her compositions to orthogonal grids. Her recorded aim for her work was to create space, movement and light.

In 1931 Moss was a founder member of the Association Abstraction-Création – a loose collection of non-figurative artists brought together by Georges Vantongerloo, Theo van Doesburg, Jean Arp and Auguste Herbin. The original membership of 41 included Mondrian, Naum Gabo and Kurt Schwitters. Eventually many others joined, among them Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. As an exhibiting and publishing organisation, it represented the unification of numerous factions of international abstract art, growing as it did from previous movements: De Stijl, Cercle et Carré and Art Concret. Throughout the 1930s Moss exhibited regularly in Paris with various societies: the Association 1940, Les Surindépendants, Les Salon des Réalités Nouvelles and the Groupe Anglo-Americain. In her early paintings of the period, especially those exploring the effects of close parallel lines (the so-called ‘double line’), the dialogue is certainly with Mondrian. Indeed, she spent time with him in his studio, not far from her Montparnasse apartment. In later work there are more similarities with her other close contemporaries and friends: Vantongerloo, Jean Gorin and Max Bill. Along with these international artists, she developed a Constructivism from the Russian movement synthesised with Parisian Purism and Neo-Plasticism. This was a vibrant and flourishing scene, and Moss was at the heart of it, showing her work at the 1937 exhibition Konstruktivisten in Basel and in the 1938 Tentoonstelling Abstracte Kunst at the Stedelijk, Amsterdam.

On her arrival in Lamorna, she set about transforming her temporary studio (lent to her by the Impressionist painter Stanley Gardiner) into her favoured clean white space, and, following Mondrian’s advice, wrote to Ben Nicholson in St Ives. She wanted to initiate some sort of association with a view to exhibiting, and explained that she would like to discuss ‘the possibilities for Abstract work in England at this moment’. Although the two of them had previously shown side-by-side under the umbrella of Abstraction-Création, they had not yet met. Nicholson didn’t respond. She wrote again a year later before receiving a reply. For reasons that can only be speculated upon, they did not collaborate.

Moss did not let this disappointment deter her and continued to pursue opportunities to make connections with British artists. In 1949 she exhibited locally in Mousehole, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that she achieved more significant recognition in England, with two solo shows at Erica Brausen’s Hanover Gallery in London.

There was a brief moment in 1954 when it seemed a community could be formed. Paule Vézelay invited Moss to join her in the organisation of a British branch of the Groupe Espace, a pan-European association with an interest in the synthesis of art and architecture. Moss responded with enthusiasm, but sadly Espace UK became a dispiriting debacle of clashing egos and quibbling, as British artists such as Henry Moore, Robert Adams, Victor Pasmore and Kenneth Martin resisted the authority of Vézelay, and perhaps also a perceived kowtowing to Europe. She contributed to the one exhibition at the Royal Festival Hall in 1955, which, in its presentation of painting, sculpture and architecture, anticipated the Whitechapel’s This Is Tomorrow.

So through misfortune rather than design, Moss ended up working in isolation. As well as her painting, she continued with constructions and reliefs - work that she had started in the Netherlands prior to the Nazi invasion. She has since somewhat erroneously been characterised as a peripheral figure and an eccentric recluse. Some members of a younger generation of Cornwall artists did try to seek her out, and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham even described her as a phenomenon, but no contact was made.

Not surprisingly, Moss is far more widely known in the Netherlands, with major retrospectives in the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s. Her works are held in several national collections there, as well as elsewhere in Europe, New York and Jerusalem. Sadly, she remains little known in England, her home country. Maybe this would not have perturbed her; in 1955 she wrote:

Art is – as Life – forever in the state of Becoming.