“The Big Five” is what scientists call the earth’s major known extinction events, during each of which more than half of the planet’s species were destroyed. The most recent was 65 million years ago. According to a survey conducted in 1998 by the American Museum of Natural History, seven out of ten biologists believe the world is now entering a sixth.

In 1796 the French paleontologist Baron Georges Cuvier delivered a lecture on the fossil of a giant sloth recently discovered in Paraguay. In it, he effectively proved the existence of extinction; animals once walked the earth, he said, that today are no more. He became a proponent of the theory of catastrophism, according to which mysterious cataclysms had intermittently wiped parts of the planet’s biological slate clean.

It is not known when John Martin first encountered Cuvier’s ideas. The painter arrived in London from Northumberland in 1806, at the age of seventeen. He was the son of a farm labourer and a devout Protestant mother, and the filthy, bustling city must have widened his young eyes. But by the 1830s, when Martin had become internationally famous as the painter of thunderous, apocalyptic tableaux, Cuvier was a personal acquaintance and an occasional visitor to his studio. It was not uncommon for scientists and engineers to commingle with artists, writers or even theologians; early nineteenth-century England was a society in flux, subject to forces of rapid change that threw together disciplines and beliefs in a maelstrom of uncertainty. A growing metropolitan populace was eager to enjoy the conveniences and entertainments of industrialisation, but was also bitterly conscious of the gulf between their own lives and the extravagant Regency aristocracy. Neither side of the social divide had yet decided whether progress was something to fear, or something to embrace. It was, in short, a time not wholly unlike our own.

Despite Cuvier’s refusal to admit religious doctrine into his work, he must have been influenced by the era’s vogue for millenarianism – that is, the belief that seismic global change is imminent. In its Christian form, it derives from the Book of Revelation, which predicts Jesus’s second coming, his defeat of Satan and the establishment of heaven on Earth for 1,000 years (“Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land”, as millenarian William Blake put it in 1804). It reflected popular anxieties over modernity: fear of the coming apocalypse tempered by anticipation of the utopia that would follow.

Whether Martin was a millenarian or not is still the subject of dispute. Certainly his eccentric brothers – collectively known as the “Mad Martins” – were, and indeed his older brother Jonathan was also genuinely mad, setting fire to York Minster and subsequently being institutionalised in St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics. Ruthven Todd, Martin’s biographer, unearthed an advertisement from 1848 for a book on the British Israelites (a fringe group of millenarians) “with designs by John Martin”, though neither the book nor any other link has been found. On the other hand, Martin’s friend Ralph Thomas described him as a “thorough Deist” – that is someone who saw proof of God’s existence not in scripture, but in the marvellous workings of turnerthe natural world. Martin also devoted the majority of the last two decades of his life to schemes for the betterment of London, particularly its smelly and polluted river; as historian Lars Kokkonen points out in an essay for Tate’s show catalogue, he made no connection in these projects to his own religious beliefs. Nor, apparently, did he disapprove of London’s industrial modernity, but thought it “the most wealthy, civilised, and enterprising city in the world”.

Whatever Martin’s private convictions – or lack of them – there was undoubtedly something in the air. Random occurrences took on portentous significance. When, in 1815, a giant volcano erupted in Indonesia, the dust cloud obliterated the following year’s entire summer, and street hawkers sold pamphlets announcing the death of the sun. Percy Bysshe Shelley and his teenage mistress Mary fled London for Geneva where they stayed with Byron (much of Mary’s novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was written there). Also, in 1816, Martin exhibited Joshua commanding the sun to stand still upon Gibeon at the Royal Academy. Although received dubiously by the Academy’s members, the painting was a hit among the viewing public, perhaps because its depiction of the prophet, marshalling with raised arms the elemental forces that swirled about him, was a tonic for the helplessness most people felt at the time. Martin became renowned for giving his public what they wanted, and was often derided because of it. He was an accomplished printmaker, and his affordable mezzotints hung in homes all around the world. But he was never elected as a Royal Academician, and was condescended to by the artistic establishment. (John Constable called him a “painter of pantomimes”.) By and large, he rose above such sneers. There is evidence, however, that the ambitious working-class artist was conflicted about his social standing: some, such as the painter Charles Leslie whom Martin once embarrassed at a concert by hissing throughout the National Anthem, saw him as something of a radical. This was despite Martin’s close friendship with Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and even Prince Albert, whom he reportedly received at his house in dressing gown and slippers.

Part of his popularity might be attributed to his skill at sanitising the decadent and raw products of Romantic culture. He absorbed Edmund Burke’s theory of the Sublime – that sensation of delightful terror elicited by vast, rugged vistas – and tailored it for mainstream tastes. J.M.W. Turner, fourteen years Martin’s senior and an acquaintance, though hardly a friend, achieved the critical recognition that the younger artist craved. The two men were markedly different: Martin was, by all accounts, a charismatic conversationalist and a snappy dresser; the reclusive Turner, according to Martin’s son Leopold, was “untidy; a sloven and unwashed”. Compare, as author Barbara Morden does, Turner’s vaporous Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning After the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis 1843 with Martin’s painting of the same subject, The Assuaging of the Waters 1840.

Turner’s is a disorientating vortex of figures and symbols swept up in rich pigment and atmosphere; Martin’s, though also dynamic, proffers its symbols – a white dove, a raven, a snake, some shells and fossils – up front and crisply rendered. It does not take long to decipher.

John Martin

Plate from Illustrations to the Bible: Belshazzar's Feast 1835

Mezzotint on paper

19 x 29 cm

Photo: Tate Photography

Which was fortunate, for people queued up in droves for the chance to view Martin’s paintings. When William Collins purchased Belshazzar’s Feast in 1821, more than 5,000 people paid to see it. Appealing to the zeitgeist, the painting describes the moment during one of King Belshazzar’s lavish, drunken parties that the writing appeared (literally) on the wall. The receding colonnades and vertiginous viewpoint (what Martin called “a perspective of feeling”), combined with dispersed areas of detail, left many viewers not knowing where to look. So Martin told them, publishing a numbered diagram listing not only the characters, but the order in which one’s eye was to apprehend them. He was, essentially, anticipating the manipulative effects of cinema while still constrained to a single, painted image.

Belshazzar’s Feast was also a set. Its imposing columns and ornate decoration established the tone, and then terraces and plazas, separated by flights of steps, provided stages on which the action could unfold. When filmmaker D.W. Griffith needed a template for the “great gate of Babylon in the time of Belshazzar” for his epic Intolerance (1916), it was to Martin’s painting that he turned. His camera’s point of view was necessarily static (this was before the days of dollies or Steadicam), so the set had to do the job of directing the viewer’s attention about the screen. In fact, Martin had been doing this from the beginning. He was a poor figure painter, and an even worse portraitist, but he compensated by telling his stories through landscape and weather.

For film producer and animator Ray Harryhausen, Martin’s paintings were an important and acknowledged influence. Because Harryhausen’s innovative Dynamation technique, which he developed in the 1950s, required a locked-off shot for the superimposition of monsters or other special effects, it suited him to approach the design of a set as if it were a picture. And Martin’s architectural fantasies (which were themselves influenced by John Nash’s grandiose Regency schemes) provided rich source material for films such as Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Clash of the Titans (1981). (In fact, among Martin’s prints are also some sensational pictures of monsters – produced for paleontologist friends who commissioned him to flesh out their fossilised dinosaur bones.)

Disaster movies have always been popular, but in recent years their themes have increasingly migrated from the fanciful to the prophetic. The Day After Tomorrow (2004), Inception (2010) and, notably, 2012 (2009) have all ripped up panoramic (in their case computer-generated) landscapes to conjure the cataclysms of the near future, much as Martin did in his own late-period blockbuster The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3. Even real-world disasters such as tsunamis, earthquakes, or extreme weather events, not to mention terrorist atrocities, are now filmed by their victims at the vividly close quarters that previously only Hollywood productions could achieve. Ever since the collapsing World Trade Centre exceeded what anyone thought possible, cinematic catastrophes have had to be bigger and more convincing. IMAX and 3D cinema are no longer solely the preserve of documentaries on Sublime subjects such as space travel or undersea exploration. Martin’s paintings, with their dizzying detail and macro-perspectives, were the IMAX films of their day.

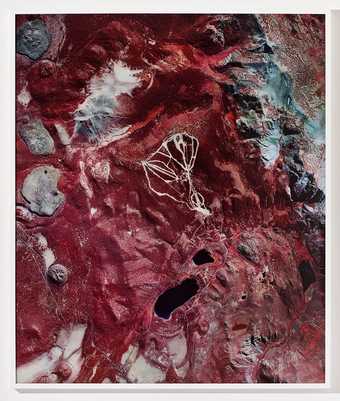

Edward Burtynsky

Oxford Tire Pile #8, Westley, California, USA 1999

Dye coupler print

68.6 x 86.4 cm

Courtesy Flowers Gallery, London © Edward Burtynsky

Florian Maier-Aichen

Above June Lake 2005

C-type print

218.4 x 184.2 cm

Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles © Florian Maier-Aichen

Mike Nelson

TripleBluffCanyon

Installation view of at Modern Art Oxford 2004

Courtesy Modern Art Oxford and Matt's Gallery © Mike Nelson

It is not only cinema that uses a Martinian sense of bigness to make its viewers feel small. Now that digital photographs can be printed at the scale of large paintings without losing clarity or detail, it is natural that the medium should suggest itself to artists exploring the contemporary Sublime. Andreas Gursky might be seen as the principal of a certain school of dystopic vastness that also includes Florian Maier-Aichen and Edward Burtynsky. All these photographers, like Martin, favour elevated perspectives on to vistas that recede to infinity. Burtynsky in particular shares Martin’s inclination to compose his images around a central void or recess, as with his photographs of quarries or tyre piles. His pictures from 1996 of bright red nickel pollution in Ontario instantly recall Martin’s lurid visions of fiery damnation.

For the most literal experience of immersion, however, pictures cannot rival installations. Is it a coincidence that the main exponents of the genre of hyperrealist “total installation” (Ilya Kabakov’s term) – Mike Nelson, Christoph Büchel, Gregor Schneider and Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe – all have a taste for the pre- or post-apocalyptic? Or that their work is equally popular with exhibition visitors? Critic Roger White, in his title for an essay on these artists, categorised their approaches as “aesthetic edutainment”, which is also an apt phrase for what Martin intended with his paintings.

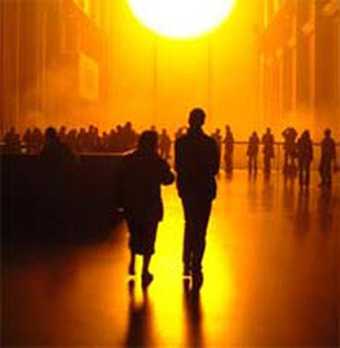

The Weather Project, Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson’s installation for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2003, prompted many viewers to lie on the floor, gaze up at the mirrored ceiling, and imagine themselves floating in the immersive, yellow space. When Martin submitted his painting Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion to the Royal Academy in 1812, he was amused to hear that the framers could not at first tell which way round to place it in the frame. In this, and other works, Martin used the pictorial device of a waterfall to twist the horizontal plane of a conventional landscape into an up-down proposition (up to heaven, down to hell). When Eliasson installed The New York City Waterfalls, in 2008, he left all the nuts and bolts showing – creating secular, but no less awesome, models of the Martinian Sublime.

Photograph of Olafur Eliasson's New York City Waterfall (2008)

Courtesy Public Art Fund, New York © Olafur Eliasson

Some artists might not consider comparison with the sensationalist and shrewdly careerist Martin much of a compliment. Anish Kapoor’s sculptures and installations elicit the “ooh wow” response that drew nineteenth-century viewers to Martin’s work. Inspired (ominously) by the Tower of Babel, Kapoor’s ArcelorMittal Orbit will loom over London’s Olympic site in 2012, at twice the height of Britain’s current tallest sculpture. It will be an icon of funfair-Sublime, with a restaurant at the top. Other artists, such as the Los Angeles-based Marco Brambilla, knowingly pastiche the melodramatic absurdity of both Martin’s brand of apocalypse and its contemporary, cinematic equivalent. Evolution (Megaplex) 2010 is Brambilla’s history of mankind retold in a 3D collage of Hollywood blockbuster imagery; the video Civilization (Megaplex) 2008 scrolls slowly upward through kaleidoscopic fireballs and furnaces to the plains of heaven.

Towards the end of Martin’s life, Cuvier’s catastrophism was slowly superseded by uniformitarianism, a theory that subscribes to cumulative, incremental changes in geology and ecology. That paradigm persisted until the latter decades of the twentieth century, when primeval catastrophes such as meteor strikes, floods or sea-level changes were once again entertained in evolutionary debate. The consensus today is that a combination of the two applies, but also that, when reflecting upon mankind’s ruinous impact on the earth, it is no bad thing to submit our imaginations to the kinds of hellish – and heavenly – visions of the future that Martin brought into the world.