Ai Weiwei

Study of Perspective – Tiananmen Square 1995–2003

Gelatin silver print

38.9 x 59 cm

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

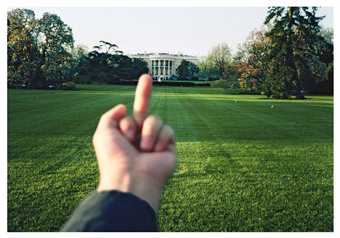

Ai Weiwei

A Study of Perspective – White House 1995–2003

C-type print

38.9 x 59 cm

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

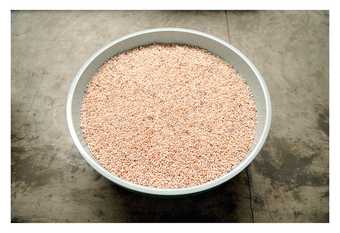

Ai Weiwei

Study of Perspective – Mona Lisa 1995–2003

Gelatin silver print

38.9 x 59 cm

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei has his reservations about the idea of ‘the masses’, although there is certainly a sense of immensity to many of his works. His large-scale sculptural installations, from his chandeliers (Chandelier 2002, crystal and scaffolding, to Template 2000), the 1,001 wooden doors and windows from destroyed Ming and Qing Dynasty houses (1368–1911) and Bowl of Pearls 2006, (porcelain and freshwater pearls), are all labour-intensive productions. But there is a lot more to his works than the pure expansion of scale and accumulation of volume that fittingly lend a monumental and handsome quality to them.

Ai Weiwei’s Template in his studio, Beijing 2007

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei

Bowl of Pearls (detail) 2006

Porcelain bowls and freshwater pearls

Each 43 x 100 cm

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

One of his most well-known endeavours, Fairy Tale 2008, involved taking 1,001 Chinese volunteers, mostly first-time visitors to a foreign country, to Kassel, Germany, in five groups throughout the course of the 2007 Documenta 12. The logistics were almost unthinkable and dauntingly complicated. He had their wristbands, outfits, suitcases, beds and sheets designed, manufactured and shipped from China. They were accommodated and fed in a former textile mill, with chefs being flown in from Ai’s Beijing neighbourhood. His team had to deal with every detail of this grand adventure – the passports, visas, transportation, accommodation and food – and recorded it to produce a 150-minute film. The project could be best described by a dazzling array of impressive numbers, peaked by its budget of $4.1 million. The implausibility of the idea, as far-fetched as a fable, dissolved itself in the power of one man to mobilise so many resources and trust in the art world to make it happen.

Ai Weiwei

Descending Light 2007

Installation view, at Mary Boone Gallery, New York

Glass, crystal, lights and metal

400 x 663 x 461 cm

Photo: Adam Reich

Courtesy the artist and Mary Boone Gallery, New York © Ai Weiwei

Yet Ai’s relationship to mass is more thorny than smooth. He has a deep-rooted distrust in the political system, or any system in fact, that operates on conditioning and manipulating the consciousness of the mass population who have gradually become docile, unquestioning and self-censored. His father, the famous poet Ai Qing, and his family fell victim to the political movements of the 1950s, in which the population was fully mobilised and misled to launch a ruthless and unstoppable revolution. The great potential and extreme atrocity of a mass movement were both released at the same time. Having left China for America in the early 1980s, Ai Weiwei was exposed to – and took snapshots of – some of the most dynamic activist movements for civil rights in the United States, particularly on the streets of New York, which helped to instil an unwavering belief in individual freedom and social justice in his young mind. As he realised back in the 1980s and the early 1990s, the following decades would be the period when the individual was at war with the system.

Ai Weiwei

Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo 1994

Han Dynasty urn, paint

25.4 x 27.9 x 27.9 cm

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

Since he returned to Beijing in the 1990s, Ai has consciously expanded his role as an artist to be actively engaged in projects that contribute to the growth of his artistic and social clout. He edited and published collections of fellow artists’ concepts and proposals, wrote catalogue essays for them, curated exhibitions and co-founded an art space. Aware and wary of the smallness and economic limitations of the art industry, he diversified his practice to include architectural designs and urban planning. Among the dozens of projects his design studio FAKE Design took on, there was the consultancy for the Beijing Olympics national stadium, in collaboration with Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron. His subsequent denouncement of the 2008 Games, after having played such a key role in the conception of the stadium, was further proof of the contradictory and difficult position he’s placed himself in towards the power system, which consistently energises his thinking and work.

His prominent architectural track record and open criticism of the government, which was voiced on his blog since 2005, alongside visual evidence of his thriving art career internationally, began to attract more and more public attention. He had 17 million readers in its four-year lifetime. It was eventually shut down by the authorities after Ai continuously published findings from an investigation he helped to launch and support to track down the exact number and individual names of the students buried underneath badly constructed schools in the deadly earthquake in the south-western province of Sichuan in May 2008. Corruption of the governmental officials involved in commissioning the construction of these schools was covered up, while Ai and his fellow activists wanted to expose the hidden truths and the darkness and absurdity of their public disguises. He was also a strong advocate of boycotting the government’s installation of software, ‘the Green Dam’, in every computer sold in the country to filter and censor content deemed sensitive. His heated opposition cost him the closure of his blog, yet it was such a successful and influential self-publishing platform that Ai developed a heartfelt commitment to communicate to a mass population of internet users, mostly youngsters, in China. He has since turned to Twitter, the instant messaging social network, on which he now spends eight hours a day browsing and writing. In addition to making announcements about his upcoming exhibitions and uploading pictures of his latest travels, events and visits, Ai has quickly adapted his mode of communication to the nature of Twitter, which allows only 140 characters for each entry. There are now more exchanges between Ai Weiwei and his thousands of followers that are online around the clock. He’s named the online community he’s created on Twitter ‘Cao Ni Ma Guo’, the sound of which is tantamount to ‘the kingdom of fuck’, evoking a clearly defiant attitude that runs through his character.

Ai Weiwei

Rooted Upon 2009

Installation view at Ai Weiwei’s studio, Beijing

Courtesy the artist © Ai Weiwei

Ai has come to appreciate the enormous potential of such internet tools to reach a large number of young readers. He has been distributing more than 10,000 copies of documentary films he’s made about the private investigations he’s involved in to expose the problems of the political and legal system in the country, his petition for a Chinese activist lawyer, his confrontations with the police and so on. The receivers of these films will show them to their families and friends, and the size of the audience immediately doubles, if not triples. It’s no wonder that he considers his communications on Twitter as a form of education for a younger generation of Chinese people, who had otherwise received a simplified and unified view of the world from schools. ‘I almost see it as a school,’ he has said.

The complex and multifaceted nature of Ai’s thinking and practice challenges anyone’s understanding of art and the role of an artist. It’s becoming harder and harder to differentiate his public activities from his art-making, and any attempt to make such a distinction seems rather pointless and unimaginative. Ai Weiwei fluidly translates some of his discoveries and perceptions of life through his social engagements into his artistic practice and fuses them with emotion and force. In his solo exhibition at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, ‘Ai Weiwei: According to What?’, he created Snake Ceiling, a serpentine installation comprising hundreds of black-and-white backpacks for elementary and junior high school students in memory of the children killed in the Sichuan earthquake. At Munich’s Haus der Kunst, he used 9,000 children’s backpacks to spell out on the façade the sentence ‘She lived happily for seven years in this world’ in Chinese characters, a quote by one of the earthquake victim’s mothers. It was the centrepiece for his solo exhibition, So Sorry.

Ai Weiwei

Snake Ceiling 2009

Installation view at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Photo: Watanabe Osamu

© Ai Weiwei

A woman stands amongst the debris of the earthquake in Sichuan Province, South West China as rescue workers look for survivors, May 2008

Ai’s determination to identify each individual name of the 5,000-plus school children among the earthquake victims has clashed with the government’s self-contradictory claims and the deep-seated paradox of the country. In name, the people have been given the foremost importance in the founding principle of this communist country. Yet in essence, the people as a collective are both faceless and powerless, living in the shadow and at the mercy of the privileged few. Ai’s work looks at the profundity and complexity of such a reality in its face.