Mark Godfrey

Several recent artworks have explored the subject of migration and border zones, especially in the region of North Africa and Europe. These pieces raise a number of questions relating to the ways artists tackle the visibility or invisibility of migrants, and to the relationships between documentary and fiction. Why do you think there have been so many important works around this subject?

T.J. Demos

This subject has become a major source of artistic investigation over the past decade, and continues to grow today (the upcoming Manifesta [a European biennale], for example, intends to place Europe and North Africa in dialogue). It marks a shift from the preoccupation with the idea of nomadism in the 1990s, a form of artistic mobility that was quite affirmative and celebratory in the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the liberalisation of China. With the eventual crisis of globalisation and the failure of many of the promises of neo-liberal capitalism, we’ve seen borders emerge everywhere. For many, that has been a poignant sign of a global inequality. Several artists based in Europe have focused on borders as a way of investigating these new conditions that are increasingly defining and dividing our lives politically, economically and socially. For example, for his film Capsular (2006), Herman Asselberghs (who’s based in Brussels) recorded the ferry journey from Algeciras to Ceuta, the Spanish enclave located in Morocco, tracing the geographically ambiguous edge of Europe’s southern boundary, which many Africans attempt to cross illegally.

Mark Godfrey

What is interesting about Capsular is the way Asselberghs describes the lack of anything to see on the journey between one place and another, despite the fact that 1,000 migrants drown on the Strait of Gibraltar each year. In his voiceover he says: ‘For all the constant circulation of explicit media coverage exposing global misery and pain, you note [on the journey to Ceuta] a remarkable lack of truly memorable images of this death zone. Keeping these people off screen as much as possible seems part of a policy to render their lives present as a threat.’ His exploration of the dynamics of visibility and invisibility is fascinating, as he comments later on the constant recording of images around Ceuta: ‘On the outskirts of town runs a fence equipped with video cameras, magnetic, seismic and infrared sensors all uplinked to satellites to allow remote viewing from a central command post. You are of course not allowed to film.’ At this point he revisits the earlier comment and says: ‘Keeping these people on screen at all times seems part of a policy to render their lives invisible.”

Stills from Herman Asselbergh's Capsular 2006

Courtesy Auguste Orts, Brussels © Herman Asselberghs

T.J. Demos

You’re right: his interest lies in the politics of appearance, in terms of tracing a geography where migrants are rendered largely invisible. The people who are desperately trying to get into European space are visually erased; in that sense his film (which shows no migrants) repeats the invisibility that occurs in reality. He compares this system, at least from a European perspective, with ‘capsular’ living, of being contained in a hermetically sealed space, like a greenhouse (his title comes from Belgian philosopher Lieven De Cauter’s book The Capsular Civilisation). The film’s premise is that by rendering invisible those who want to enter Europe, we erase their lives – and their deaths. Capsular attempts to shatter the greenhouse.

Mark Godfrey

Asselberghs’s film ends in Brussels and considers the lives of migrants in the city, but I find it interesting that so many other artists who look at crossings between Europe and Africa, and who are based in places such as Brussels, Berlin, Paris or London, tend not to pay attention to the life of migrants all around them in their home cities, but instead head for the locations of crossings, as if migrants’ struggles take place only at these sites. In so doing, they treat the border as if it is still a single place, or a line that exists on a map.

Ayesha Hameed

I agree. This is the afterlife of migration, and your point calls attention to what extent that part of the journey is rendered visible or invisible. Once migrants reach their destination the discourse in art turns more towards identity politics and culturally specific shows, so that the conversation focuses more on static sites of multiculturality, as opposed to these fluid or mobile zones of crisis which render a certain point of their journey visible. When you talk about borders as a regime of visibility in this afterlife, those that migrants encounter are not necessarily visible. The borders themselves as they operate in the city become more complicated as they are more visible to those that can’t cross them, or they’ve become operationalised around these clusters of multicultural zones, and in the art world, in the organisation of shows that focus on national origin or ethnic identity.

Mark Godfrey

Eyal, your research has shown the spatial complexity of borders – that different kinds exist all around us – and it suggests that the understanding of a border as a line or a single place is now obsolete.

Eyal Weizman

The logic of separation has fractured. Rather than being linear and continuous, as in the geopolitical imagination of the Cold War, borders these days are fragments, splintering across and through ‘deep space’ within cities, between neighbourhoods. Cut apart by border and segregation devices, space is woven together by highly policed and intensely filtered networks of transport and communication. Checkpoints and borders mean that sovereignty (of a state, an institution, a corporation) is exercised in its ability to block, filter and regulate movements across its boundaries. The global politics of separation are embodied in the way in which ‘internationals’ – people with business or security clearance – move swiftly across most borders, but ‘foreigners’ – undesirables without appropriate papers – are stopped, delayed and often detained at most thresholds, physical or national. Within this larger system architecture operates as a valve regulating the flow of passengers under the volatile global regime of security.

The location of government has thus shifted to transport nodes and networks. To a large extent, the function of government is that of valves modulating the ‘mobility regime’. Borders of states (at the airport), much like boundaries of buildings, are thresholds that function both as filters of movement and as media spheres, a combination of sensors and archives that register and store information about everybody and everything that passes through them. Every act of crossing is also always an act of registration. Every act of registration is an act of archiving. It is the crossing of thresholds that we see in the CCTV video of the Israeli assassination team in Dubai issued by the emirate’s police. All movement across borders and boundaries has been registered. Contemporary spaces thus no longer seem fixed; rather, they are elastic, almost liquid.

The linear border, a cartographic imaginary inherited from the military and political spatiality of the nation state, has splintered into a multitude of temporary, transportable, deployable and removable border synonyms – separation walls, barriers, blockades, closures, road blocks, check points, sterile areas, special security zones, closed military areas and killing zones – that shrink and expand the territory at will. These borders are dynamic, constantly shifting, ebbing and flowing; they creep along, stealthily surrounding buildings, infrastructures, villages and roads. They may even erupt into one’s living room, bursting in through the house walls. The anarchic geography of the contemporary space is an evolving image of transformation, which is remade and rearranged with every political development or decision. Some security structures might be evacuated and removed, yet new ones are founded and expand. The location of security apparatus is constantly changing, blocking and modulating traffic in ever-differing ways. Mobile policing stations create the bridgeheads that maintain the logistics of ever-changing operations. The military makes incursions into towns and refugee camps, occupies them and then withdraws. Separation walls are rerouted, their path registering like a seismograph the political and legal battles concerning them. Where territories appear to be hermetically sealed, tunnels are dug underneath them. Elastic territories can thus not be understood as benign environments: highly elastic political space is often more dangerous and deadly than a static, rigid one.

The dynamic morphology of these spaces resembles an incessant sea dotted with multiplying archipelagos of externally alienated and internally homogenous ethno-national enclaves under a blanket of aerial surveillance. In this unique territorial ecosystem, various other zones – those of political piracy, of ‘humanitarian’ crisis, of barbaric violence, of full citizenship, ‘weak citizenship’, or no citizenship at all – exist adjacent to, within or over each other.

To return to art, it seems to me that the ‘design of separation’ is also an intervention in the field of vision, and as such is similar to artistic documentary techniques. A film-maker artist whose work in this area I greatly respect is Florian Schneider. He took five seconds of CCTV video footage showing migrants climbing the Ceuta border fence and asked how this would operate within mainstream media. He was interested in what editing processes this image would go through and reconstructed and somewhat reversed these. CCTV cameras take a much lower rate of frames per second than television, and when transferred to TV the pictures are speeded up. In this case it made the migrants appear like a swarm of ants trying to invade. Schneider’s understanding of the border as a media ecology means he has chosen to work on the ‘source code’ of the image.

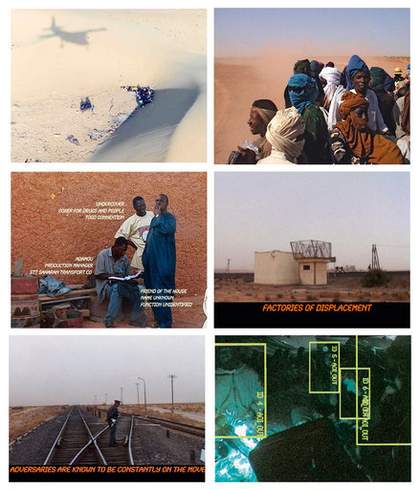

Stills from Ursula Biemann's Sahara Chronicle 2006–7

Multi-screen installation

Courtesy the artist © Ursula Beimann

Mark Godfrey

Another work exploring the movements of migrants is Ursula Biemann’s Sahara Chronicle 2006–7, a multi-screened installation of videos documenting the Saharan exodus towards Europe. Whereas Asselberghs produced no images of migrants in order to indicate the ways in which they are kept invisible, Biemann recorded all sorts of people – migrants, Tuaregs who facilitate passages across the desert, truck drivers and so on. She also interviews those who’ve failed in their attempts to migrate. Since the 1970s there have been many debates about the problems of ‘concerned documentary’ practices – one thinks of Martha Rosler’s critique, for instance. How do you think Biemann copes with those debates that warn one against what it means to take such images of disadvantaged people?

T.J. Demos

It’s different from the history of socially concerned documentaries because Biemann invites people to speak for themselves on camera. She presents a multiplicity of views, which is crucial to her goal of ‘mobilising complexities’ rather than ‘documenting realities’, as she puts it. Her work is very sophisticated about images, sensitive to the fact that they carry no immanent meaning, but rather gain value via different contexts and usages (in this regard, it’s important to recognise her work’s basis in an interdisciplinary research practice that she organises alongside her videos). We should resist claiming that migrants are invisible in the mainstream media, which tend to produce sensationalised human interest stories. These depictions typically show the living conditions of migrants and the difficulties they encounter on their journeys. What Biemann does that’s so valuable is investigate the larger social, political and economic causes of migration, not simply its anthropological effects. She examines the financial mechanisms (of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, for instance) that have turned African countries into failed, indebted states, dotted with enclaves of protected natural resources commanded by multinational corporations. One sees this in her portrayal of the Tuaregs’ disenfranchised relation to the French control of uranium mining on their traditional lands in Niger, or in her exposure of the European demands for fishing licences off the coast of Mauritania forming a system that economically damages local industry. Her goal in Sahara Chronicle is not to create sympathy with victims, but to allow people to articulate a demand for political inclusivity and economic justice, a demand to enter into a relationship with Europe, rather than being cut off and forgotten.

Mark Godfrey

However, at times the people Biemann films are saying that they wish to enter into a capitalist system for a certain amount of time, to do as well as they can, to work hard and then return to their homeland. Their demand is not so much for political equality, recognition, or justice, but for an economic opportunity. Do you think she pays enough attention to those particular motivations?

T.J. Demos

While it’s true that migrants desire higher standards of living, the problem is that with the increasingly militarised EU-sanctioned border security – as in the high-tech fences around Ceuta shown in Asselberghs’s film, or in Libya’s use of desert surveillance drones in Biemann’s video – they are driven to desperate measures to fulfil their hopes. Security is no answer.

Mark Godfrey

Biemann has particular ways of installing Sahara Chronicle, which seem to be as important as the content of the piece itself…

Eyal Weizman

Yes, I think that the form of the film work, the method of its making and how it is installed need to be considered together. It’s important to bear in mind the filming collectives and research networks she’s set up for it. Not all the footage is actually shot by her. She acts as a director across great stretches of time and space. Often standing at the littoral of the Sahara, that first ‘sea’ that migrants from sub-Saharan Africa have to cross, she manages to populate it with different groups and complex politics.

Ayesha Hameed

I think her work complements that of collectives such as Multiplicity, who also employ multichannel formats. One installation of Sahara Chronicle consists of two large-scale projections of aerial territorial mappings of the space, coupled with monitors screening interviews on the ground with headphones. This allows for a movement between scales and a mutual imbrication of different modes of narrativity, which as you mention is further enabled by different crews who followed their own respective trajectories across the desert. As a result, there’s a simultaneous presentation of these different nodal points. There’s no claim to create a coherent or overarching linear narrative. Multi channel works such as this enable a certain type of mapping of space and of narratives, and shifts in tones.

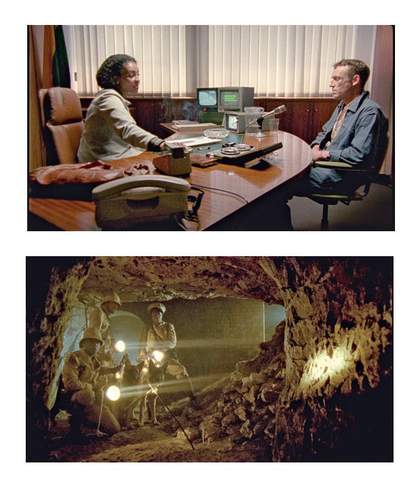

Stills from Omer Fast's Nostalgia 2009, video installation in three parts

Courtesy the artist, gb agency, Paris, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, Postmasters, New York © Omer Fast

T.J. Demos

She is strategic about how she installs her work. Its complexity suggests an analogy for the multiplicity of the site that she’s investigating, which is invariably geographical, militaristic, economic and political. In that sense it’s quite different from the presentation of Omer Fast’s Nostalgia (2009), where you have videos placed one after the other, which proposes a spatial trajectory in the gallery that mirrors the unfolding of the work’s fictional narrative.

Mark Godfrey

Nostalgia is an installation in a sequence of three separate spaces. First one sees a video of a British park keeper constructing a trap to catch game. Then you move into a darkened room with two screens showing a reconstruction, using actors, of an interview between Fast and a British-based, African-born immigrant whom the artist talked to in London. During the course of the interview the guy remembers being taught how to make a trap like the one we saw being made in the previous video. After listening to the conversation for five or so minutes you move into a third space where there’s a much larger single projection which is a fictional film. This is set in the future: there is a tunnel between Africa and Europe, and white Europeans are attempting to flee for economic reasons towards Africa, while encountering different problems on the way.

Eyal Weizman

I have looked at this work in terms of narrative structure, rather than the theme of immigration. For me, it isn’t an obvious political allegory. There is this physicality of the trap that is seen through the knowledge transference, in terms of the way it is orally described and replicated across time. It is constantly being misplaced in conversation and in another situation. In a sense, the building of the trap is continually located in a different social relation, and it is the trap that is a hinge that makes constant inversions. The shift between Africa and Europe I think is just one of the inversions that occur around that physical and social apparatus. So it is more intricate than a simple way for us to understand what it would be like to be a migrant in a different place.

T.J. Demos

But does the film set a trap for the viewer, inviting us to imagine ourselves in the position of the asylum seeker? As Susan Sontag writes in Regarding the Pain of Others, the documentary tendency to create sympathy for victims produces an imaginary proximity to those who are suffering, one which allows viewers to forget their responsibility for participating in the larger situation (via our representative governments) that perpetuates the conditions of violence. Think of the action sequence in Fast’s film when the African security guards hunt down a group of British trespassers in the tunnel. Once they’re caught, the soldier pours gasoline on a young woman and appears poised to set her on fire. But just before it happens the film loops back to its beginning, to a scene where an interrogator is lighting her cigarette. Borrowing from Hollywood techniques, Nostalgia lets you imagine yourself as a migrant, but at the cost of overlooking our own participation in the system of exclusion.

Mark Godfrey

I think the idea of the trap worked very well in a number of ways. It was just this tiny fragment of the conversation Fast had with the migrant that became useful for him as the structuring device for the whole piece. The man’s description of the trap allowed the artist and the viewer in turn, to think about the traps of making works about this kind of subject matter. Perhaps one of the main traps is the idea that if a work tries to tackle the questions around migration in the most factual ways possible, it will somehow be a more legitimate response to the situation.

Fast’s introduction of fantasy in Nostalgia certainly negotiates this trap. In this respect we can connect his work to Francis Alÿs’s project in Gibraltar, where he asks questions about what the role of the poetic might be in relation to the political. In August 2008 he organised an action which took place simultaneously on a beach in Morocco and in Spain. Groups of children were given a series of shoe boats – little constructions that Francis had made from cheap sandals or Moroccan babouches, with sails on them. The children were asked to carry the shoes out in a line into the waves. Of course they would never be able to form a bridge to the other coast and were constantly rebuffed by the waves. However, underlying the action was a fantastical proposition about the desire of the younger generation to ignore or transcend the types of borders that keep apart Europe and Africa.

T.J. Demos

It is fantastic to have an image of a bridge, as the idea of a two-way connection has become so alien to the political reality in which we live. In this regard, it’s important to point out that all the artists we’re discussing are opposed to these increasingly conservative politics, and are developing ways of visualising a different future. Also, the fact that the boats don’t ultimately connect represents an acknowledgement that this is not a pragmatic solution to a problem. Alÿs’s is a productive use of utopia – not escapist or apolitical, but one where utopia is latched on to as a critical force against the intolerable reality that exists, and as a creative proposal for an imaginative alternative, expressing the power of what could be, and what might yet be.

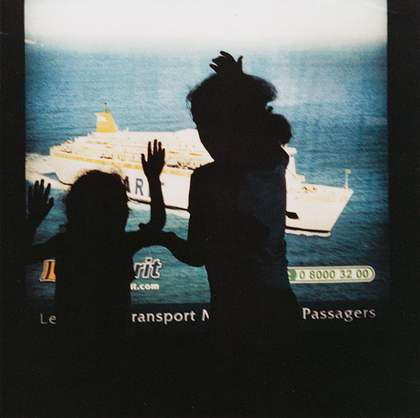

Yto Barrada

Advertisement lightbox, Ferry port transit area, Tangier 2003

C-type print

70 x 60 cm

Courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris © All Yto Barrada

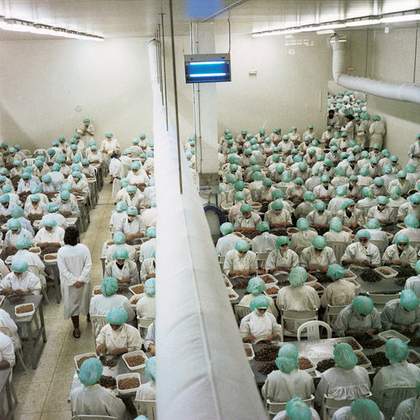

Yto Barrada

Prawn processing plant in the Free Trade Zone, Tangier 1998

C-type print

100 x 100 cm

Courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris © All Yto Barrada

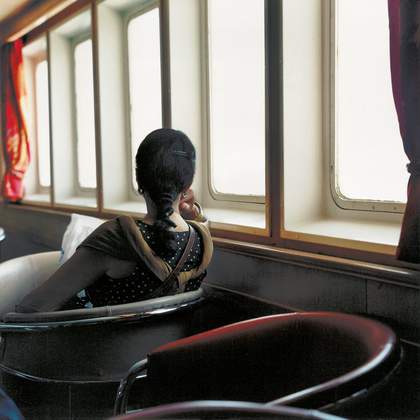

Yto Barrada

First class lounge, ferry from Tangiers to Algeciras 2002

C-type print

70 x 60 cm

Courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris © All Yto Barrada

Yto Barrada

The Strait of Gibraltar, reproduction of an aerial photograph, Tangier 2003

C-type print

70 x 60 cm

Courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris © All Yto Barrada

Ayesha Hameed

I wonder what these failed gestures mean if you reconfigure them in terms of the motif of childhood and the ephemeral materials that he’s using. What does it mean for these boats not to cross? What does that do in terms of inflecting the discourse of crossing or failed migration? More ‘serious’ work enables a certain kind of discourse. But then what happens if you transpose this discourse on to these fragile objects and utopian impulses that, say, Walter Benjamin locates within the consciousness of children? This brings us back to our previous consideration of inversion and displacement in Fast’s work. There’s this other harsh reality that haunts the background of such playfulness. In ‘la jungle’ in Calais, for example, a lot of the migrants are children travelling on their own and facing specific legal issues and forms of detention. The utopic in this instance has a materiality that invokes the very non-utopic materiality of these journeys.

Mark Godfrey

We have been talking about artists who are mainly based away from this region, but I thought it would be important to end with Yto Barrada, who works in Morocco. Her photographic book and series The Strait Project: A Life Full of Holes (1998–2004) is an extraordinarily interesting book in which several kinds of photographs are juxtaposed – images she has taken, found aerial views of the Strait of Gibraltar, almost abstract landscape shots and so on. She writes very well about the ‘metonymic character’ of the Strait and the tension between its real identity as a ‘harsh’ place and its ‘allegorical’ identity as a place which inescapably stands for something larger – the crossing point of continents and cultures; she describes her ambition to explore this tension.

T.J. Demos

As she points out in her accompanying statement, as a Moroccan artist she’s very aware that it was only in the early 1990s, with the construction of the EU’s Schengen zone and the fortification of its borders, that the Strait effectively became a one-way passage, restricting African access to Europe. Despite this fact, she’s made the passage back and forth. Her photographs powerfully portray the often contradictory and paradoxical reality of Moroccans’ thwarted desire to be elsewhere. We see people from behind, turned away from the camera as if they’re departing. Often she focuses on walls, which appear as visual barriers. One has been repeatedly marked with a football that people have kicked, expressive of an aggression towards borders. A shot of the side of a rusty steel container suggests an imaginative cartography. The visual field, in other words, becomes a surface on which are projected the desires for liberation as well as the frustrations of enclosure.

Mark Godfrey

There is a real sadness to the book which is in very sharp contrast to the kind of playfulness and hope in Alÿs’s work. In her text on the project, Barrada describes the desire of Moroccans to leave for Europe as a ‘fatal drive’.

T.J. Demos

Yes, but Barrada’s practice is also very important because she’s maintained her basis in Tangier, where she runs a cinematheque – a site for independent film screenings and distribution in North Africa. She remains committed to local production and brings cultural resources to her region. This commitment to staying in itself brings with it a kind of hope.