When I visited John Baldessari, the first thing he showed me after introducing me to his dog, Giotto, was a reproduction of a Velázquez he saw recently at the Prado – a painting he appreciates for the way its representational imagery yields to a kind of embedded abstraction. Such an interest in Old Masters might seem odd for an artist who famously burned most of the paintings in his studio four decades ago. That radical gesture marked the end of what one might call Baldessari’s first career (that of an abstract painter) and the beginning of his second career and emergence as a conceptual artist. But that career would come back to an intensive studio practice and an intimate involvement with making things by hand.

In the late 1960s, having studied during most of the 1950s at a handful of art schools and universities in California, Baldessari was back in the town of his youth. National City, a place he describes as not much different now than it was then, is a crossroads off the highway south of San Diego on the way to Tijuana, populated largely by servicemen and workers connected to the Navy. He returned to the town where his parents (a Danish nurse who had made her way to San Diego and an Austrian entrepreneur and jack-of-all-trades who had emigrated to the US after the First World War) had raised him and his sister. Here, he set up his studio in a failed movie theatre that his father had built. “I was filling the place up,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘If I continue this, I am going to be inundated with paintings,’ so I just called up a few friends and said, ‘If you want anything, you can have it; I am going to cremate the rest of them.’”

He saved works representing a new direction he was exploring. The rest were reduced to ashes and became the contents of a defining work in the emerging conceptual art movement. Heavily influenced by artists including Sol LeWitt and Marcel Duchamp, as well as composer John Cage, Baldessari had come to identify with the conceptual art designation. A sampling of titles from exhibitions he participated in at the time reveals both the momentum of the new movement and his immersion in it: Konzeption– Conception at the Stadtischen Museum in Leverkusen, Germany (1969), Conception–Perception at the Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles (1969), Art by Telephone at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (1969), The Appearing Disappearing Image Object at the Newport Harbor Art Museum, California (1969), Information at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1970) and Software at the Jewish Museum in New York (1970), where a plaque commemorating the cremation was displayed and an urn containing the ashes was temporarily embedded in a wall.

Shortly thereafter, Baldessari moved to Los Angeles, where he still lives in Santa Monica. Matters of timing and place are not unrelated to the shift in his work. He remembers National City as a cultural blank spot, where his contact with other artists and access to an art scene was limited: “I think the good part about it was that I had this idea of what my life might be, and I said, ‘Nobody’s ever going to see this stuff, so I’ll just do what I want.’ I didn’t feel anybody looking over my shoulder, anyway. So it was good, because I had to figure out what art was for me and what I believed, rather than receive wisdom.”

Part of what he wanted to do was renegotiate his relationship with making art, and with photography: “I was doing some sort of visual looping. I would photograph stuff that looked like the paintings I had just done, and then I would feed that back into the paintings, and then take photographs again of the paintings and keep doing this. Photography also was visual note-taking. I would pin these photographs up on the wall, just to look at for inspiration for my paintings. Then I thought: ‘Why do I have to translate this photograph into a painting? I mean, this takes a lot of time.’ And that’s where I made the leap to say, ‘Why do this? Why can’t I just use photography?’”

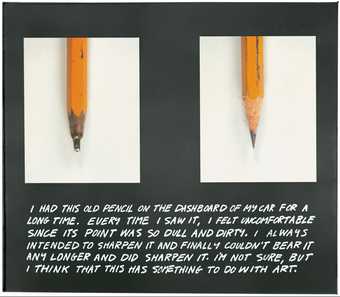

John Baldessari

The Pencil Story 1972–3

Colour photographs, with coloured pencil, mounted on board

Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © John Baldessari

That epiphany – part philosophical, part practical – went beyond the use of photography to the larger issue of removing the artist’s hand from the practice, and led to the works that were spared from the National City cremation. These were works that combined photographic images, printed directly on canvas, accompanied by simple, caption-like texts; and works that consisted entirely of painted texts which variously established narratives, or stated descriptive terms, that conventionally would appear in paintings as imagery, or would be attached to the painting by way of labelling, discussion, or documentation. Related inclinations were further explored in subsequent photographic works, as well as “commissioned paintings” made by amateur artists to Baldessari’s specifications.

John Baldessari

Hitch-hiker (Splattered Blue) 1995

Colour photograph, acrylic, maquette

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © John Baldessari

Defining of his practice was an embrace of humour, and a tendency towards producing art that, while it may appeal to more cultivated sensibility, is also accessible. For example, in his video I Am Making Art 1971 we see him repeatedly reciting the title as he raises one arm after the other consecutively, while in Baldessari Sings LeWitt 1972 he sings 35 of Sol LeWitt’s conceptual statements each to a different tune. It’s a hallmark of his work, from the earliest to the most recent, that even viewers who might be unwilling to consider it as serious art, or perhaps as art at all, can still understand his humour and his approach. That long-present quality is something the artist sees as deriving from an interest in pulling away from a more cloistered idea of art practice. “What would happen if you just gave people what they want?” he recalls of his early thoughts on the matter. “And I think the other thing that’s informed my work a lot was teaching. I did it just to support myself, but then it fitted back into my art, in that I realised that art was about communication… you wouldn’t be a closet artist. I thought, ‘Why not? What’s wrong with communicating?’

“One of the things that had interested me was trying to sidestep my own good taste,” says Baldessari of his move towards working with found images, “because each time you do something, you get more acute in your visual sensibility. And so I said, ‘I will somehow have to find ways to block myself, because a sensibility is going to bubble up to the surface anyway; so why not?’” Such thinking has infused his art ever since, and is evident in the practice of intuitively and calculatedly reworking and recombining found images that has shaped works of the past three decades. “I guess you can only do so much of what I call armchair philosophy,” notes Baldessari, who comments that he doesn’t see the term conceptual art describing what he now does. “You just have to try it out and see if it works. And sometimes a really dumb idea works, and conversely a really good idea doesn’t work.

“I get really attracted to details and parts of things. I used to tell people I would feel happy if there was just one square inch of a painting I liked. I wouldn’t even have to like the whole painting.” Such a fondness for fragments, combined with a general dislike of how photography imposes formats on images and a tendency to think of words and images as interchangeable, drives his practice. “That’s where my interest in writing comes in; it’s getting the right word next to the right word that’s important… it’s syntax,” he says about the juxtapositions in his work.

“Clutter, I think,” he answers when asked what he needs around him to work, tracing his fondness for mining society’s endless supply of pre-existing imagery to his days in National City, both as a young artist who looked to books and magazines as a way to “import” his culture, and as a boy growing up with a father who, prone to salvaging and recycling, saw use-value in everything. “I would drive my studio assistants crazy,” says Baldessari, unable to kick habits born of a childhood often spent pulling nails out of used lumber and reconditioning old hardware. “I would fish paper out of the trash and I’d say, ‘This is usable paper. Why are you throwing it away?’” It is of little surprise that dumpster diving is among the methods he has used over the years to obtain the images he works with. The scavenger is also a constant worker. “A friend of mine once called me a nine-to-five artist, and he was right,” smiles Baldessari, comfortable in the house/studio compound he’s currently expanding in anticipation of the loss of his other studio of many years in a building slated for redevelopment. He takes pleasure in a routine that begins with early-morning reading followed by exercise, and then work until the dinner hour. He maintains this schedule seven days a week, interrupted only by art excursions and travel, community obligations such as sitting on the board of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and projects including curating and designing exhibitions and, more recently, redesigning the logo for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – activities the artist attributes to perpetual restlessness and a desire to continue challenging himself.

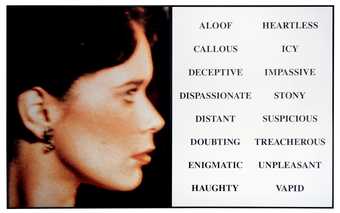

John Baldessari

Prima Face (Third State): From Aloof to Vapid 2005

Archival digital photographic print, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © John Baldessari

This routine also used to involve teaching. His presence was a major factor in the ascendancy of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in the 1970s and 1980s. And following a hiatus from the classroom in the early 1990s, Baldessari, at a time when he certainly didn’t need to do it to support himself, took up a post at UCLA, which he only recently ended. “I think it’s selfish,” he says of a teaching career that is in fact defined by generations of artists who count him as a generous mentor and a major influence. “I get a lot out of talking to young artists. You know, they’ll be the first to tell you you’re full of… you know, they’re not your peers, and they’re the future, so it’s interesting just to hear what they’re thinking about. And what I give back is that, I think, I’m pretty adept at helping students to get to where they want to go faster.”

It was early in his teaching career that Baldessari recalls catching his first glimpse of some social purpose of art. The realisation came when, working as a fill-in teacher at a camp run by the California Youth Authority, he swung a deal with his students. If they would try to pay attention in class, he would get them after-hours access to the facility’s arts and crafts shop. “Here were these kids, and we had no shared values – you know, they were criminals. And yet they had more of a need for art than I did. And I said, ‘Art must do them some good.’ Before that, I thought I would become a social worker. I had kind of a religious background as a kid growing up, and I had thought, what good did art do? It didn’t help anybody. And now I thought, well, I guess it does help somehow.

“I haven’t got beyond that,” laughs the artist when asked what he thinks art does now, “just that I guess it provides some kind of spiritual nourishment, as corny as that sounds, for people, I guess.” Baldessari shrugs, hinting at his Protestant ethic when asked about his devotion to making art: “Again, that’s very religious. I figure whatever you do, you should do the best you can.”