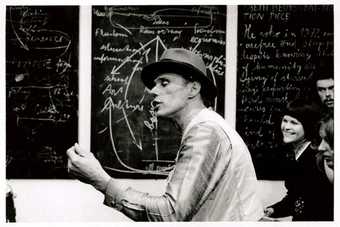

Fig.1

Joseph Beuys

Information Action 1972

Performed at the Tate Gallery, 26 February 1972

Photo: Simon Wilson

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Seven Exhibitions 1972

On 26 February 1972, Joseph Beuys presented a lecture and discussion as part of his contribution to a group show, Seven Exhibitions, held at the Tate Gallery. He titled this artwork Information Action and Tate’s internal and external communications described it as a performance.

Staged in the Duveen Galleries, the large central space in what is now Tate Britain, the work consisted of Beuys lecturing on innate human creative capacity and the potential power of direct democracy to shape society. He illustrated his ideas by chalking his conceptual schema on three blackboards and engaged the assembled crowd in free-form, often tense, discussion (fig.1). The participating audience seems to have numbered in the dozens (precise numbers are unavailable, as the show was free of charge and unticketed). We know from photographs and a surviving audio recording of the proceedings that the artists Richard Hamilton and Gustav Metzger were among those attending (and among Beuys’s most aggressive interlocutors).

Joseph Beuys

Four Blackboards

(1972)

Tate

Subsequent viewers are most likely to encounter Information Action through photographs or in the form of the blackboards he used on the day, which after resting in the store of Tate’s Education Department for eleven years were accessioned into the museum’s permanent collection in 1983 and thus deemed artworks themselves. They are pictured here along with a fourth board Beuys used for a similar performance on 27 February 1972 at the Whitechapel Gallery (fig.2). Read conventionally, these elements can only gesture back towards Information Action – as a photograph frames a fleeting moment, the blackboards bear the tenuous residue of the artist’s vanished presence. They are reminders that we missed the action.

Speaking from the present moment, the action-based quality of the work poses a problem of access, an existential threat to the performance itself and, therefore, it would seem, to the viability of the work for later audiences. Moreover, usual modes of art historical investigation and gallery display – ones that might pair the blackboards with a photograph or an explanatory text as an aid to a spectator’s time travel – run the risk of radically altering the nature of the performance, turning it into an inert object of contemplation about a discrete event that occurred in an extinct past. Or, expressed more simply, the symbolic remnants of the artists’ own purported (and equally irretrievable) subjective intentions.

By focusing, however, on the role played by the various media in and through which Beuys conducted his lecture – precisely those artefacts to which we do have access – analysis can do greater justice to the piece, both as it was and as it is. The blackboards were not innocent bystanders: far from functioning as mere receptacles of ideas or energies, they anchored and specified a relation between artist, audience, and artwork. Such social relations, moreover, were the performance’s primary area of concern; interrogating their configuration leads to what is arguably the still-beating heart of the work.

Much has been said about Beuys’s pedagogical mode and his self-understanding as a messenger of special knowledge. For example, in an interview with Beuys conducted a few months after Information Action, Richard Hamilton asked him about potential similarities between that work (in which he lectured on politics to a crowd of people) and another performance, the deceptively literally titled How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare 1965.1 Hamilton’s implication was that Beuys’s missionary pose verged on condescension. In 1980 art historian Benjamin Buchloh echoed this suspicion, couching a critique of the notion of politics as performance in an ad hominem attack: ‘Beuys’s magnetism seems to result from a psychic transfer between his own hypertrophic unconscious processes at the edge of sanity and the zombie-like existence of his followers’.2 Marianne Wagner posed the problem more delicately in an essay of 2009, stating that, ‘To what extent Beuys’s forms of teaching were in practice actually able to achieve audience participation in an open forum … or whether he just gathered an audience around himself, is something that has to be critically appraised’.3

Fig.3

Joseph Beuys

Information Action 1972

Performed at the Tate Gallery, 26 February 1972

Photo: Simon Wilson

Tate Archive Photographic Collection: Seven Exhibitions 1972

Crucially for Information Action, the extent to which Beuys did ‘achieve’ participation had to do with how he staged a collision of two institutional frameworks – university and museum – in the name of democracy. The blackboards supported Beuys’s role as instructor; as props they carried this message even before the first lines of chalk struck their surface. Tate’s own formats of presentation and preservation also served to position Beuys at the work’s centre. Photographs feature the artist surrounded by onlookers, while a microphone projected his voice to the edges of the space and traced it onto the recording soundtrack (fig.3). It is no accident, then, that when people have approached this work from a later moment, it is Beuys’s activity that seems its most salient aspect, even though it is also – paradoxically – the very thing that cannot be re-presented and can only be retrospectively suggested. This has resulted in the sense that Beuys’s works exist now principally as remains that offer clues to what it was like to be in the presence of the man himself and what effects it might have wrought on those who were with the self-styled teacher-politician at the Tate Gallery.

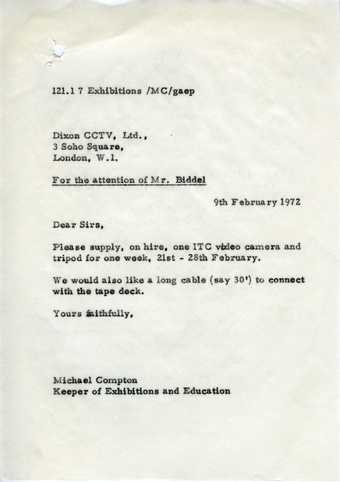

Fig.4

Michael Compton

Letter to Dixon CCTV, 9 February 1972

Tate Archive TGA 931/53

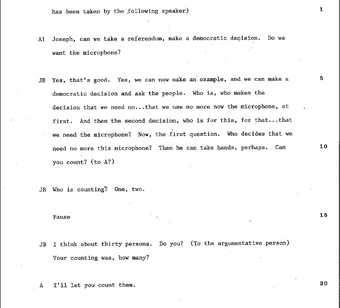

Fig.5

Transcript of Information Action 1972 (excerpt)

Tate Archive TAV 616AB

Download the full transcript as a pdf here.

At the same time, however, this collision of frameworks heightened the audience’s awareness of how the nominal content of Information Action was shaped by its material modes of delivery (fig.4). In the intersection of classroom and gallery, the way institutional forms engendered social relations became visible. Even on 26 February 1972 there was no immediate conduit through which to receive Beuys’s ‘psychic transfer’, only the experience of how such an interpersonal exchange was conveyed through the material elements of the specific situation. One audience member suggested that the use of a microphone worked at cross-purposes with Beuys’s stated aims in that it distributed the power of speech unequally among those present. The notion found considerable traction with the audience and eventually the assembled held a referendum to decide on the fate of the microphone (fig.5). They voted – and Beuys was quick to frame the decision-taking as an object lesson in direct democracy – to continue using it.

In the end, however, the precarious microphone played the protagonist not because it survived its referendum to deliver a complete accounting of what transpired on the day but because the fact of its having been imperilled points to the work’s most profound lessons. Whatever Beuys’s intentions, democracy was put forward not as an abstract ideal or a practice that could be willed into existence at any moment but, rather, was made visible as the ways and means through which relations between people were organised. The microphone did not merely amplify or record what happened but structured what could happen in the first place. Far from dematerialising art by placing a lecture in its frame, Beuys’s performance materialised social relations. Politics and pedagogy became more than the content of a discussion, and the gallery became more than a mute container for experience. By bringing his pedagogical methods into the space of art, Beuys continues to say more about democracy than could have been contained in a single lecture.

When we look at photographs of Information Action or behold Four Blackboards in a gallery setting, we should not see remnants of an artwork that once was or the relics of a saint of the church of performance. What we see are embodiments of fundamental problems of political and social life – who gets to speak, by whose authority, and in what manner of address? Beuys’s outsized proclamation that ‘everyone is an artist’, that all people have the power to shape the world, was at its root a search for form. The irony of Information Action’s legacy is that it stands as testament to the fact that he had not found the right one. This realisation suggests that the work is far from over. What is more, it reminds us that content can never be separated from form, especially when dealing with art’s most evanescent actions.