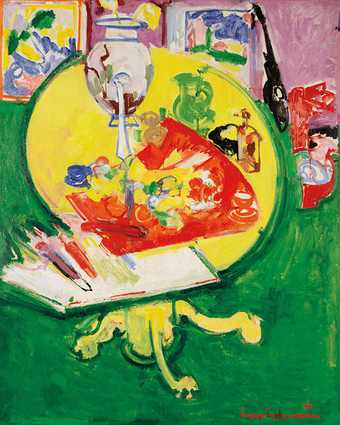

Fig.1

Hans Hofmann

Pompeii 1959

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 2140 x 1327 mm

Tate T03256

© The estate of Hans Hofmann

How do we make sense of Hans Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959 (Tate T03256; fig.1) – a vibrating, flowering canvas, thick with accreted paint slabs and blotches of colour? Like other ‘slab’ works – the name used for the paintings of rectangles that the artist began making in the eighth decade of his life – Pompeii offers us a collection of vertical and horizontal slabs, each its own solid colour, floating on the canvas. The painting possesses a kind of logic: rectangles abut yet never overlap, and are gathered and stacked in ways that suggest a play with modular construction, their heights halving or thirding the heights and widths of their neighbours, or protruding ever so slightly beyond another slab’s horizon. Yet this logic evaporates, above and below the slabs, in open seas of colour: a swathe of aqua blue spreads out in thick, oily smears, and blurry patches of reds and browns offer only the barest hints of geometry. Small daubs and dots of bright colour – green, orange, royal blue, red – hover at the interstices of various passages, as though inchoate slabs themselves that are yet to assume the definition and right angles of the composition’s major shapes.

Surface and depth

Fig.2

Cover of Prolog: Programming for Artificial Intelligence by Ivan Bratko, 3rd edn, Essex 2001, featuring Hans Hofmann’s Pompeii 1959

Does Pompeii suggest expression and subjectivity? Perhaps the slathered aqua blue and simmering reds are signs of emotion and expressiveness: the turbulent contours of the artist’s self. Or does Pompeii lead us in a different direction, to the structure and order of the modern world: bright but impersonal, cheery but systematic? Gracing the cover of a 2001 programming textbook, the hovering slabs of Pompeii appear as the bounded but flexible components of a language or data set, with the potential for dynamic but logic-oriented configurations (fig.2). Or perhaps Pompeii suggests a more physical modernity: not the artificial intelligence of present-day computer science, but the city grids and skylines of mid-century urbanism. The painting’s palette is no less suggestive. These could be the lush colours of nature, a Matisse-inspired pastoralia for the post-war moment, or the slick and gelatinous colours of kitsch – the shades of a commodified world offered up for delectation.

Hofmann’s Pompeii compels the viewer in large measure because it fails to resolve such questions with any finality. The painting’s immediacy – its sensual appeal through colour and texture – is matched by an equal obstinacy and opacity with regard to interpretation. It is not that Pompeii resists analysis, but that it tends to sustain competing, even highly contradictory readings at once. Like Hofmann’s oeuvre at large, Pompeii holds several of modernism’s competing philosophies in suspension, as though in a chemical solution: floating within its bright palette we glimpse modernism’s various romances with materialism, spirituality, expressionism, logic, transcendence and banality. Before our eyes, it vacillates between something with deep reservoirs of meaning and something that is all surface; it points back to the histrionics of the abstract expressionist canvas and ahead to the cool, smooth forms of colour field painting and, beyond that, to the psychedelic colours of 1960s design.

Hofmann’s trajectory

Hans Hofmann occupies a curious role in the history of American painting, at once central and peripheral, well-studied and undervalued. Part of the New York School of painters from its beginnings in the mid-1940s, Hofmann was the first of his peers to be described as an ‘abstract Expressionist’,1 and was lauded as a quintessential practitioner of mid-century painting by both Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, arguably the two most influential critics of the era. Hofmann was one of the ‘irascible eighteen’ painters who penned the now-famous letter to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, protesting the institution’s ‘hostil[ity] to advanced art’, an episode that launched the signatories into public consciousness as a defined artistic group.2 Yet Hofmann was not present for the iconic photograph that Life magazine ran in their coverage of the group eight months later (he was at his second home in Provincetown, Massachusetts), an absence emblematic of the artist’s ambivalent status within abstract expressionism throughout his life.3

Aged fifty-two when he immigrated to the United States from Germany in the early 1930s, Hofmann was an established painter and teacher well before he joined the abstract expressionist milieu. When a youthful Jackson Pollock was posing, James Dean-like, in the pages of Life magazine under the question ‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’, Hofmann was sixty-nine.4 Furthermore, Hofmann’s primary identity, especially in his early years in America, was that of teacher, not artist. After teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and the Art Students League in New York, Hofmann established his own art school, with locations in Manhattan and Provincetown, where he instructed an extraordinary range of artists – Burgoyne Diller, Ray Eames, Allan Kaprow, Lee Krasner, Marisol and Joan Mitchell among them. During his own lifetime, reviews and articles often noted how, despite being ‘a painter of some reputation in Munich before coming to this country, [Hofmann] has been known here chiefly as a teacher’.5 The Museum of Modern Art in New York did not acquire a canvas by Hofmann until 1956, nearly a decade after it purchased Pollock’s She-Wolf 1943.6

Fig.3

Hans Hofmann

Still Life – Yellow Table on Green 1936

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas

© The estate of Hans Hofmann/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.4

Hans Hofmann

Spring 1944–5

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2017 Estate of Hans Hofmann/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.5

Hans Hofmann

The Window 1950

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Compounding the generational and pedagogical issues was (and is) Hofmann’s own diversity of style. He created fauvist-like landscapes, Matissean interiors (such as Still Life – Yellow Table on Green 1936; fig.3), explosive drip paintings, as seen in Spring 1944–5 (fig.4), thick clotted swirls (see, for instance, Liebesbaum 1954, R. and H. Batliner Art Foundation, Vaduz) and cubist-inspired abstractions structured by the tracery of overlaid lines and angles (as in The Window 1950; fig.5). Like other abstract expressionists, he found his way to something of a ‘signature’ style, in his case in the slab paintings of the late 1950s and the 1960s such as Combinable Wall I and II 1961 (fig.6) – although he did so comparatively late and he continued to make and exhibit other kinds of works alongside them. The question of how to synthesise this body of work into a coherent reading of the artist – let alone into a reading of his role in abstract expressionism or American modernism – continues to vex scholars. One element that connects Hofmann’s various styles is his bold and original use of colour, which gives the works (from the early landscapes to the gestural impasto paintings to the late slabs) their bold, dazzling and sometimes even harsh appearance. But Hofmann’s use of colour has introduced its own set of problems for the artist’s reputation. Are the colours perhaps too bold and vibrant, as critics have suggested?7 Do they align his work rather closely with pleasures too easy, literal and sensual? Do they suggest that most fraught of concepts – decoration – and thus consign the paintings to something less than serious high art – to the realm of the feminine, the trivial or the commercial?

Fig.6

Hans Hofmann

Combinable Wall I and II 1961

University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

© The estate of Hans Hofmann

Pompeii opens onto a host of divergent directions and interpretive paradigms. This In Focus travels along several of those routes, allowing the painting to shed light on four distinct issues. It examines Pompeii’s (and Hofmann’s) transnational dimension, arguing that questions of travel and translation are central to its meaning and reception. It discusses Hofmann’s role within the critical genealogies of abstract expressionism, showing how he served as a limit case for critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg in their writings. The study explores Hofmann’s three mural commissions, two of them realised and extant on New York buildings, in relation to slab paintings like Pompeii, and a contribution from curator and art historian Elissa Auther analyses how Hofmann’s colour, facture and rhetoric played into period concerns about decoration. Pompeii, and this In Focus, thus leads us into several issues at the heart of modern American art, from its transnationalism, to its critical construction in the early post-war years, to its role in the built environment and, finally, to its hierarchies of taste.