A good Hofmann has to have a surface somewhere between ice cream, chocolate, stucco, and flock wallpaper. Its colors have to reek of Nature – of the worst kind of Woolworth forest-glade-with-waterfall-and-thunderstorm-brewing.

T.J. Clark1

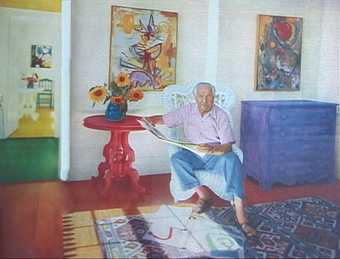

Fig.1

Hans Hofmann

Pompeii 1959

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 2140 x 1327 mm

Tate T03256

© The estate of Hans Hofmann

Art historian T.J. Clark’s colourful description of Hans Hofmann’s work in his 1999 study Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism expresses a reaction to the artist’s style associated, in the art world of his day and beyond, with the concept of the decorative. It is not hard to imagine the lush, impasto surfaces and vibrant palettes of Hofmann’s classic slab paintings – Pompeii 1959 (Tate T03256; fig.1) included – being the target of Clark’s acerbic comments. In this essay, I consider Hofmann’s painting practice in relation to the history of the decorative, a long-maligned aesthetic that artists working in abstract idioms have struggled to negotiate in an art world that has historically privileged the intellectual over the sensual.

As applied to works of art, the term ‘decorative’ is a judgement against objects that are perceived to be minor and subordinate, that revel in surface-level expression and that exemplify good taste over any commitment to intellectual rigour or cultural critique. An equation with physical forms of décor – wallpaper, furniture, textiles – is often implied, reducing the work of art to the status of a common commodity. Clark’s assessment of Hofmann demonstrates how this plays out rhetorically: a good Hofmann, he continues, ‘can have no illusions about its own status as part of’ the ‘visceral-cum-spiritual upholstery of the rich’.2 Related to the decorative as an overly composed, surface-oriented aesthetic, Clark’s description also targets Hofmann’s palette, linking the decorative to the long-standing suspicion of colour as a cosmetic treatment that dissembles or creates the mere ‘look’ of art.3

While nothing quite as hyperbolic as Clark’s reading of Hofmann’s style ever appeared during the artist’s lifetime, his work was, by virtue of its abstraction, vulnerable to dismissal as mere decoration. Coinciding with the rise of abstract expressionism in New York, the decorative reappeared as a term of judgment fuelled by intersecting anxieties over the potential slippage of abstraction into what were perceived as lesser, conceptually empty visual forms like design, and the encroachment of commercially driven cultural forms upon high art generally. The force behind the revival of the term was the American critic Clement Greenberg, who, in his seminal essay ‘The Crisis of the Easel Painting’, described the decorative liability inherent in abstract expressionism as rooted in the ‘all-over’ composition, which, dispensing with traditional principles of composition, flattened space and evenly dispersed pictorial incident across the canvas in a manner akin to a patterned textile or wallpaper. Although his position on the decorative could be contradictory, Greenberg’s overall objective was to reinstate painting’s independence from the world around it.4

More than ‘mere décor’

Hofmann, like many painters of his generation coming of age in artistic circles centred in Munich and Paris in the early twentieth century, was familiar with a more flexible and sympathetic understanding of abstraction’s consonance with decoration. This conception positioned abstract painting as an antidote to the isolated pictorial tableau. Thus, the abstract painting, decoratively understood, was not the antithesis of high art, but rather an alternative to a conception of painting as a window onto another illusory world. Furthermore, this conception suggested an integrated relationship between art and architecture, since the abstract painting, rather than being assimilated to a pre-existing scheme, played an active role in defining or transforming space. Despite these nuances, this conception of the decorative met Greenberg’s through the shared goal of protecting abstract painting from a descent into a dependent status as ‘mere décor’.5

One can see this at work in Hofmann’s practice. While he demonstrated flexibility with regard to abstraction as a decorative form, as evidenced by his three architectural mural commissions, he still worked to distance his easel painting from the concept of decoration.6 In his writings, and presumably in his teaching, the term ‘decorative’ frequently appeared and he defined it in opposition to ‘decoration’. In a 1952 artist’s statement Hofmann made a series of points regarding the decorative that are representative of the complex meanings of the term in relation to his work. He wrote:

There is a difference between ‘decorative’ and ‘decoration’. Decoration is based on design. Design in the usual sense results from taste only. Taste is not a creative faculty. The function of design is ornamentation. As such it is either art or it is not … To be truly decorative presumes the faculty of plastic and esthetic creativeness. A decorative work is basically always a plastic work of art. It is de facto two-dimensional in concept and de facto two-dimensional in execution. Design that does not result from plastic and esthetic experience will only produce empty flatness … This is then bad design.7

The plasticity Hofmann was looking for in his own work, and which he believed distinguished the decorative as a form of abstraction from a lesser design solution, is further revealed in his theory of colour interaction known as ‘push and pull’. In Hofmann’s words,

Push and Pull is a colloquial expression applied for movement experienced in nature or created on the picture surface to detect the counterplay of movement in and out of depth. Depth perception in nature and depth creation on the picture-surface is the crucial problem in pictorial creation.8

Hofmann’s application of his push and pull theory is exemplified in his ‘slab’ paintings, such as Pompeii. In this work, the juxtaposition of coloured areas – primarily rectangles – create movement within the canvas as passages of the composition recede away from or move towards the viewer, resulting in his signature effect: the floating rectangle. Hofmann viewed this type of movement as essential to the creation of authentic compositional form in opposition to abstraction that he defined as more akin to design, the opposite of the ‘plasticity’ he hoped to achieve. Yet Hofmann’s technique, which involved pinning coloured paper rectangles to the surface of the canvas to test their interactions, was a practical, problem-solving approach that would not be out of place within the field of design. In fact, Hofmann was introduced to the use of movable coloured rectangles for composition planning by a studio assistant who was helping him scale up his preparatory drawings for the mosaic mural at 711 3rd Avenue in New York – a practical design requirement of the commission.9

Colour: Sensation and suspicion

If Hofmann’s theory of push and pull had connections to his experience working on architectural commissions that tested his acumen for design, as seems likely, it might also have been shaped in part by a desire to rehabilitate the status of colour in painting, which is intimately linked to the decorative in the history of art. The prominence of colour in Hofmann’s work was (and remains) an oft-noted aspect of his practice, from his own extensive writing on the subject, to Clark’s cutting comparison of his palette to Woolworth kitsch, to a 1957 Life magazine profile that introduced him as ‘a painter of explosively coloured abstractions’.10 Pompeii’s raucous palette of hot, high-key yellows, pinks, reds and blues is an ideal illustration. There is a longstanding association of the decorative with the excessive pleasures of colour in the history of art, inherited from classical philosophy, that characterised it as cosmetic, decorative, seductive and thus a dangerous force. In the seventeenth-century disegno vs. colore debates, colour was more explicitly associated with the feminine body and positioned as a moral and aesthetic threat to masculine line, which was associated with an opposite set of values – language, reason, perfection and thus truth.11

These suspicions of colour and its association with the decorative were inherited in turn by modern artists, who, like Hofmann in his theory of push and pull, did their best to reposition its compositional role as central to the creation of form rather than a subordinate element that poses a threat to order. Although in Hofmann’s philosophy colour is privileged over line, thus overturning the hierarchy that historically suppressed it, colour was nevertheless still discussed as a ‘problem’. Colour, Hofmann insisted, is ‘not a creative means in itself. We must force it to become a creative means’.12 Considered in relation to the history of colour’s inferiority, Hofmann’s push and pull theory, which harnessed colour for constructive purposes, also looks like a disciplinary tool used to tame colour’s excesses. Hofmann’s approach elevates colour’s function, differentiating it from its unbridled use in decoration or design where it cannot play a constitutive role in the determination of form.

‘Living in a Painting’

Fig.2

Lead image from the article ‘Living in a Painting: Hans Hofmann Has Made His House a Series of “Still Lifes”’, Look, 28 July 1953, pp.52–5

Photo © Michael A. Vaccaro

Paradoxically, the carefully theorised, anti-decorative position Hofmann created for his painting was complicated by activity that seemed to directly undermine it, especially his documented predilection for a domestic environment in which his painting was integrated into a larger decorative scheme of brightly coloured furniture and arrangements of objects.13 In the 1950s the interiors of Hofmann’s homes were featured in two lifestyle profiles in mass publications. In 1953 Look magazine ran the story ‘Living in a Painting: Hans Hofmann Has Made His House a Series of “Still Lifes”’, that conflated his art and domestic life (fig.2). ‘The unleashed colors of his paintings have come alive again in the furniture, the walls, the floors’, stated the anonymous author of the article. ‘As Hofmann uses it, colour becomes a simple sensation – like tasting a rarely flavored fruit for the first time.’14

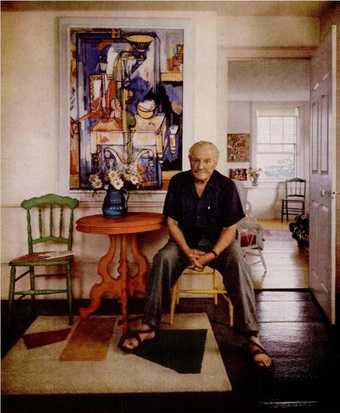

Fig.3

Full-page photograph featured in ‘A Master Teacher: Hans Hofmann Influenced Three Decades of U.S. Art’, Life, 8 April 1957, pp.72–6

© Time Inc. 2017

Photograph © Arnold Newman

The patterned rugs, painted floors and flower arrangements featured in this piece reappeared in the aforementioned 1957 Life magazine profile, which introduced Hofmann alongside photos of his students with their work, and captions that included testimonials about the influence of his teaching on their development as artists.15 Titled ‘A Master Teacher: Hans Hofmann Influenced Three Decades of U.S. Art’, the piece also included an eye-popping, full-page photograph of Hofmann in his home in Provincetown (fig.3). In it Hofmann is seated next to a semi-abstract still life painting from 1935 with a palette dominated by primary colours, which is mirrored, complemented and amplified by the colours of the interior décor of the space itself. The artist is seated on a painted yellow chair next to a table upon which sits a blue ceramic vase with white daisies. On the opposite side of the table is a painted green chair, and the floor of the room is painted a royal blue. To the artist’s left the photograph opens onto another room with more painted furniture against white walls, another flower arrangement and a patterned rug against a painted floor of a contrasting colour. The identification of abstract art with décor, implied throughout the house, is literalised in the hooked rug at Hofmann’s feet. The red, yellow and green trapezoidal shapes, arranged on a white ground, are derived from a painting that Hofmann made in 1950 for the proposed mural project in a public plaza in Chimbote, Peru; translated from paint on canvas into the yarn hooks and warp of a rug, they become part and parcel of the decorated interior. The photograph’s caption supports a reading of the interior as a three-dimensional extension of the painting: ‘Hofmann at home in Provincetown lives in a world of color provided by his own paintings and the many-hued floors and furniture painted by his wife’.16

In both of these profiles, Hofmann’s theory of colour as exemplified in his push and pull method was replaced by a more decorative reading: colour as a ‘simple sensation’, extended and brought to life in space. These reductions and generalisations are unsurprising given the popular audiences these magazines were designed to reach, and they complemented storylines about the couple’s creative approach to interior decoration designed around Hofmann’s paintings. Like Hofmann’s utilisation of coloured rectangles as a design aid, these magazine profiles complicate our understanding of Hofmann’s relationship to the decorative. Although he might have theorised the distinction between art and decoration in his published writing as definitive, in actual practice his position appears much more ambiguous. While this ambiguity might not have served him well in posterity – as evidenced by his unstable place in the abstract expressionist canon or reactions to his work such as those of Clark – it mirrors a post-war context in which the distinction between the art and the decorative was, in fact, open to debate.