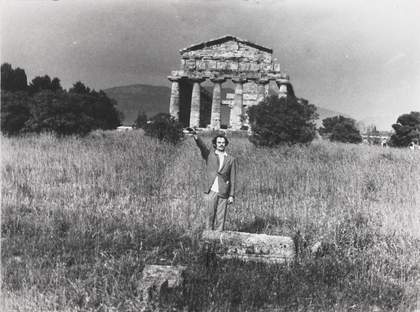

The Heroic Symbols photographs that document Anselm Kiefer’s 1969 performance Occupations hold a distinctive place in his oeuvre. They are unique in centring on the artist’s own figure, as the cultural historian and theorist Andreas Huyssen has described it, ‘performing, citing and embodying the Sieg Heil gesture … the artist seems to have assumed the identity of the conquering National Socialist who occupies Europe’ (Tate AR01171; fig.1).1 Although Kiefer has continued to evoke images of Nazi Germany in his later work, he never again inscribed his own bodily and subjective presence so directly and visibly as in the Occupations actions and the Heroic Symbols photographs. Art historian Matthew Biro has suggested that the performance constituted an ‘existentialist quest for self-identity’:2 Kiefer sought to examine the question of what it means to be a German after Auschwitz not abstractly or rationally, but as a physical experience in his own body. The aesthetic strategies of Heroic Symbols, as well as the project’s dissemination and reception history, convey an intriguing convergence of performance art and conceptualism with post-war German Vergangenheitsbewältigung, a term that translates as ‘coming to terms with the past’. Mimicry and slapstick, the manipulation and recontextualisation of historical symbols and photographic images, as well as methods of sequencing and repetition are put to work on the subject of Germany’s troubled past. A similar convergence of radical aesthetics with German history had first emerged in the performances and installations of German artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) about a decade earlier.

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

A generation older than Kiefer, Beuys has in many accounts been named his teacher. Although this description is inaccurate as Kiefer never actually studied under Beuys at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf while a student there in 1970–2, it points to the shared aesthetic and historical ground explored by the two artists.3 In their confrontation of the Nazi legacy both used performance art to yield certain social, political and psychological effects that they believed would contribute to coming to terms with this past. However, despite these shared concerns, the generational gap between Kiefer and Beuys also stands for a gap between how and with what intentions each confronted German history. For Beuys, who spent his formative years in the Hitler Youth and the Luftwaffe, and who was part of the Tätergeneration (‘perpetrator generation’), ‘the belated aesthetic confrontation with traumatic national history’, as art historian Lisa Saltzman has put it, was ‘essentially a belated experiencing of his own traumatic history’.4 By contrast, Kiefer and the Nachgeborenen generation (those born after the war), although eager to break with their parents’ silence, could not reclaim this history as ‘primary experience’.5 It is this difference in the artists’ experiential relationship with the history of National Socialism that opens a path to understanding where their artistic interventions into post-war German memory diverge, aesthetically as well as politically. This essay will explore how the distinct uses each artist made of strategies of performance art are particularly revelatory of this divergence.

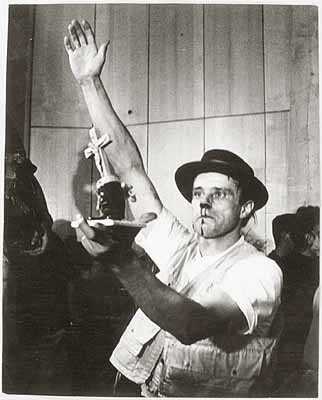

Fig.2

Heinrich Riebesehl

Joseph Beuys photographed during his performance Kukei/Akopee-nein/Browncross/Fat corners/Model fat corners at the Fluxus Festival of New Art, Technical College Aachen, 20 July 1964

© Heinrich Riebesehl

Five years before Kiefer embarked on his project Heroic Symbols in 1969, the student Heinrich Riebesehl took the now-famous photograph of Beuys with a bleeding nose, holding a wooden cross towards the camera and with his right arm extended upwards in an ambiguous salute (fig.2). The photograph was taken during Beuys’s performance Kukei/Akopee-nein/Browncross/Fat corners/Model fat corners at the Fluxus Festival of New Art at the Technical College Aachen on 20 July 1964.6 The date of the festival coincided with the twentieth anniversary of the 1944 Hitler assassination attempt, which the festival organisers declared ‘an excellent background’,7 promoting the event as ‘a commemorative ceremony of international artists’.8 The violent disruption of the festival halfway through the evening, when the enraged audience stormed the stage during Beuys’s performance, led to its location ‘between incomprehension, aggression and scandal’.9 It was the artists’ political disposition that was at the centre of the controversy. The evening opened with Joseph Goebbels’s infamous 1943 speech ‘Do you want total war?’ blasting from loudspeakers, on top of which the first performer, Bazon Brock, spoke a senseless seminar paper composed of fragments from texts by Karl Marx and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Confronted with this aggressive transgression of what was an ethical-moral and political taboo in post-war Germany, namely the public dissemination of Nazi propaganda, the audience grew increasingly agitated. The critic Dorothea Solle observed that from the outset the artists tried to confuse, provoke and intimidate, writing that their intention was to ‘fight Fascism with the methods of Fascism’, but that the desired illumination of consciousness had the opposite effect: ‘helplessness and rage’.10 By the time Beuys entered the stage, the tension in the auditorium had reached its peak. After he had melted two blocks of fat on a burner and lifted a copper staff wrapped in felt, a small explosion occurred, caused by chemicals left carelessly on the stage. This was the trigger: the audience stormed the stage, with one student hitting Beuys in the face.

Kiefer’s re-enactment of the Hitler salute in historically and politically charged settings is no doubt indebted to Beuys’s Aachen performance. In particular, it was Kiefer’s challenge to established German memory politics: his attempt to come to terms with the history of German fascism by physically and psychologically re-experiencing it, which owed much to Beuys. Heroic Symbols stands at the beginning of Kiefer’s development of a pictorial language that thematises the history of National Socialism not through absences and silences, as prescribed by the post-war West German dictum of abstraction, but through occupying precisely those cultural symbols and icons that the Nazis had brutally appropriated from German art and cultural history. The title he chose for the 1975 publication of eighteen of the Heroic Symbols photographs, ‘Besetzungen’ (‘Occupations’) indicates this intention.11 Huyssen has suggested that rather ‘than seeing this series of photos only as representing the artist occupying Europe with the fascist gesture of conquest we may, in another register, see the artist occupying various framed image-spaces: landscapes, historical buildings, interiors’ – that is, precisely those ‘image-spaces’ of the German cultural tradition (ranging from the tree and forest mythology to Romanticism) which the Nazi propaganda machine had exploited for its own ends.12

The transportation of Germany’s haunted cultural images into contemporary art was a path that Beuys had already begun to take in the performances – or Aktionen (‘actions’) as he branded them – that he had conducted in the context of the Fluxus movement. Beuys entertained an ambiguous relationship with Fluxus.13 Although he adopted much of the Fluxus format, including the performance-as-concert, the improvised adaptation to settings and events and the experimentation with artist-audience relations, he filled his actions with symbolically laden content that alluded to his own biography and national history.14 Unlike the Fluxus artists Beuys did not aspire to the total abandonment of art, but instead he sought to break down the barriers between art and life and between art and politics. This approach is expressed in his Erweiterter Kunstbegriff (‘expanded concept of art’), which he began to develop in the early 1960s (drawing on the social theories of German anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner) with the aim of initiating a new kind of art that would reshape society.15 For Beuys performance art was an artistic medium that could have such a transformative effect.

Through direct contact with his audience Beuys sought to move people into emotional and cognitive activity, to unleash their individual creativity (‘everyone an artist’), heal their sense of alienation and, ultimately, to awaken their social-political agency. His intention was to trigger a catharsis in his audience that would lead not only to a heightened awareness of history – incited by Beuys’s ‘heavy, complicated and anthropological’ symbolism – but also, and more importantly for Beuys, to a heightened sense of being in the world today.16 Thus, commenting on the injury he sustained during the Aachen performance, Beuys observed of the student who hit him in the face: ‘I can imagine that our Happenings awaken emotional centres of which the man didn’t have any control, any insight until now’.17 Echoes of the Fluxus concept of provocation as a means of creating a more engaged audience can be found in this comment.18 However, the Riebesehl photograph and its multi-layered symbolism suggests that the ‘emotional centres’ Beuys sought to awaken also stood for the process of coming to terms with the Nazi past and Auschwitz.19 While Beuys’s right outstretched arm conjures up the memory of Germany’s fascist past, his bleeding face and the cross connote religious imagery of Christ’s suffering and scenes of salvation, a reference that was further enhanced by Beuys’s giving out chocolate to the audience after his injury.20

Compared with Kiefer’s salute, the overlaying of fascist icons with religious motifs positions Beuys’s gesture in a somewhat different relation to post-war Vergangenheitsbewältigung and its conflicting dispositions of victim and perpetrator, suffering and guilt. The Riebesehl photograph soon assumed its place in art history as ‘heroic icon of the bleeding artist’.21 The translation of the religious motif of the wounded body of Christ into the wounded body of the artist has been a leitmotif in German art since Albrecht Dürer (1471–1524).22 Beuys revived this tradition, creating for himself a myth of the suffering artist and an iconography of the wound that addressed the collective historical trauma of Nazism and the destruction of the war. The mythologised story of his plane crash as a Luftwaffe pilot in the Crimea, which – so the story goes – he survived miraculously under the care of Tartars who wrapped him in fat and felt, portrayed Beuys as shaman and Christ-like redeemer: a soldier who had returned from the dead as artist and who, cleansed from his sins and suffering at war, would heal the German people.23 Critics such as Donald Kuspit have suggested that ‘Beuys’s art acts out every German’s wartime suffering in symbolic form … in his painful struggle to understand his personal suffering, he enabled other Germans to acknowledge their suffering’.24 Beuys propagated a view of art as therapeutic, creating a body of work that moved within the topos of the wound and healing. Metaphors of trauma, sickness and death, on one side, and rescue, cure and rebirth, on the other, abound in his work. The most characteristic is his signature Braunkreuz emblem, which has the colour of dried blood and is an unmistakable allusion to the Red Cross.25

In Beuys’s art the experiences of suffering and guilt and the roles of perpetrator and victim are difficult to separate. Correspondingly his art has at one and the same time been described as a ‘refutation and antidote to Nazi history and ideology’ and as ‘an unconscious reflection of the teachings of that time’.26 While a growing cohort of critics and art historians today speaks of a ‘secret’ Holocaust narrative and gestures of mourning in Beuys (referring above all to his choice of materials, colours and objects),27 the thesis that Beuys never managed to entirely liberate himself from the ‘völkisch’ and authoritarian ideas with which he was indoctrinated during his youth in National Socialism has recently also received new impetus.28 This divided reception is reflective of Beuys’s position as someone who experienced the Third Reich and who after 1945 became a leading figure of the West German student movement and its calls for social reform and a thorough working through of the Nazi past. However, in contrast to many of his student disciples, for Beuys Vergangenheitsbewältigung meant not only the confrontation of German guilt, but also working through one’s own and others’ suffering, since only then would the people be free to accept collective guilt.29 It is here that Kiefer’s aesthetic project sharply diverges from Beuys’s position and that the generational gap between the two artists becomes visibly manifest.

In line with the critical memory agenda of the Nachgeborenen generation, Kiefer’s re-enactment of the Nazi salute directly confronts the viewer with German responsibility for the horrors of the Second World War. Assuming the role of the perpetrator, his performance is an act of ‘moral self-incrimination’,30 which gives expression to his concern with the legacy of fascism in contemporary Germany and the question of intergenerational guilt. As Kiefer explained in an interview from 1987: ‘In those early pictures … I wanted to evoke the questions for myself. Am I a fascist? That’s very important, you cannot answer so quickly’.31 The art historian and critic Sabine Schütz has argued that Kiefer’s re-experiencing of fascism constitutes a critical process of self-questioning, through which he probes ‘the potential Nazi elements of his own character and possibly attains insight into the mental and psychological background of everyday fascism’.32 The choice of the title ‘Occupations’ for the 1975 publication of his earlier photographs confirms this view. The title bears not only obvious military connotations, but it also stands for the Freudian psychoanalytic concept ‘Besetzung’ that literally translates into English as ‘occupation’ but has been redefined as ‘cathexis’ to describe emotional and psychic attachments, as well as to theorise notions of loss, trauma and mourning.33

Intriguingly, despite Kiefer’s taking a distance from Beuys’s concern with suffering and healing, the reception of Kiefer has often pointed to a similar therapeutic intention in his work. The characteristic burned and damaged surfaces of Kiefer’s later paintings and photographs, as well as his use of blood and ash as artistic materials, position him in close proximity to Beuys’s aesthetic of woundedness. However, although Kiefer no doubt shares Beuys’s concern with historical trauma, and although much of his art appears to be driven by the same desire to overcome the horrors of the German past, he never confessed to the curative and cathartic powers Beuys ascribed to art.34 The utopianism that is so central to Beuys’s ‘expanded concept of art’ and his programme for a future society based on the ideals of individual freedom, creativity and responsibility is absent from Kiefer.35 Without undermining Beuys’s position, the critic Kim Levin has carefully suggested that his convergence of art and politics bears faint echoes of Hitler’s will to power, but with a twist. Like Hitler, Beuys cultivated a self-image of the Christ-like redeemer of the German people and humankind; and, like Hitler, he engaged in mesmerising performances that captivated his audiences.36 However, Levin observes that in contrast to his evil counter-player, Beuys’s flirtation with the political was directed at progressive democratic ends: ‘Instead of molding a master race, Beuys wants to make everyone an artist. Substituting internationalism for nationalism, creativity for destruction, humankind for the Volk, “living-feeling” for “race-feeling,” Green for Brown, and warmth for cold’.37

When asked about his relationship to Beuys in interviews, Kiefer has on multiple occasions rejected the older artist’s engagement with the troubled German past under the sign of self-renewal and anticipated social-political transformation. Instead, Kiefer has explained his adaptation and manipulation of the Nazis’ image-world as directed at critically examining its hold on his own and the collective German consciousness. Speaking in an interview in 1990, he described his art as ‘processing history … I attempt in an unscientific manner to get close to the centre from where events are controlled.’38 This difference between the two artists’ social-political aspirations also surfaces in the aesthetic format of their performances. Whereas the therapeutic and cathartic intentions of Beuys’s actions depended on his direct contact and exchange with his audiences, Kiefer’s re-enactments of the Nazi salute are spatially and temporally removed from the viewer. Rather than live events they are documented and mediated through photography. The camera functions as an inquisitive device and as witness to the critical process of self-inquiry and self-reflection. In 1969, the same year that Kiefer produced his artist book Heroic Symbols, he created another book with the title You Are a Painter (in German Du bist Maler). Together with his performances of the Nazi salute, You Are a Painter attests to Kiefer’s attempt to examine critically his position and responsibility as an artist and intellectual in relation to the history of National Socialism. For Kiefer the role of art and the artist in post-war Germany is not to alleviate suffering but to dig for the cultural origins of National Socialism and to reveal its afterlife in contemporary culture.39

In the work of both Kiefer and Beuys, the National Socialists’ Führer cult takes a central place. Beuys appropriated elements from Hitler’s personality cult, albeit for different social-political ends. Kiefer, for his part, mimics its embodiment in the Sieg Heil gesture with the intention of visualising its paradoxical location between the powerful and the absurd. In the Heroic Symbols photographs the absence of the cheering crowds, the quirkiness of Kiefer’s figure and its dwarf-like appearance through the distorted relations of scale render the salute ridiculous and banal. Beginning his artistic career in the late 1960s Kiefer was part of an emerging generation of artists who enrolled the previously taboo tropes of humour and parody in their engagement with the Nazi past.40 His performances involve an element of irony and self-mockery that cannot be found in Beuys, who cultivated an image of the artist as healer and saviour – a variation of the nineteenth-century concept of the artist-genius. One object that stands at the beginning of Beuys’s oeuvre, and which later also appears in Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols, namely the bathtub, illustrates this difference in artistic self-presentation particularly well.

Fig.3

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

In Kiefer’s artist book Heroic Symbols 1969 two sequential photographs that are both captioned ‘Gehen auf Wasser. Versuch in der Badewanne zu Hause im Atelier’ (‘Walking on water. An attempt in the bathtub at home in the studio’) show the artist first finding his balance on a small stool in a water-filled tub (see Tate AR01174; fig.3), and then, in the second image, performing the Nazi salute. The stool that is clearly visible to the viewer comically reveals the miraculous act as farce. Taken in Kiefer’s studio, the photographs are not only an ironic commentary on the Nazis’ delusional grandeur and their emulation of religious imagery, but they can also be read as parodying the concept of the artist-genius. By contrast, Beuys’s work Bathtub 1960 (Lenbachhaus, Munich) and its exhibition history seem to perpetuate this very notion. The piece is a small tub for a newborn baby that is bandaged up and smeared with fat. In his fictional curriculum vitae, Lebenslauf/Werklauf (in English Life Course/Work Course), which narrates Beuys’s mythologised life story as a series of exhibitions, Bathtub embodies the first line, which reads: ‘1921 Cleves: Exhibition of a wound drawn together with plaster’. Beuys described the tub as representing ‘the wound or trauma experienced by every person as they came into contact with the hard material conditions of the world through birth’.41 This universal interpretation was made historically more specific with the exhibition of Bathtub in Beuys’s retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1979. Also structured as a Life Course/Work Course, the show was divided into twenty-four stations, beginning with Bathtub, which was positioned next to the vitrine Auschwitz.42 Mario Kramer has suggested that by pairing the two works Beuys related the epitome of individual trauma – birth – to the collective trauma of Auschwitz.43 Framed by Beuys’s Life Course/Work Course, the message of this arrangement seemed to be that Beuys, who was reborn as an artist in the Crimea, considered it his task to heal post-war German society from the historical trauma of the Third Reich and the Holocaust. It is this grandeur that is absent from Kiefer’s performances, which examine mythmaking as an historical phenomenon and process, rather than trying to emulate it.