Fig.1

Barkley L. Hendricks

Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974

Oil paint on linen

Support: 1681 x 1832 x 35 mm

Tate L02979

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

In 1973 the curator David H. Katzive wrote: ‘If three different people were asked how they responded to the portraits of Barkley Hendricks … it would be entirely possible to have one person reply that they were overpowering, sensual and physically exciting; for another person to reply that they were cool, remote and photographic; and for a third person to reply that they exemplify Black dignity, pride and self-affirmation.’1 Aptly describing the range of aesthetic discourses shaping the circles in which Hendricks matured as a painter – from the political ideals of the black arts movement to the painterly concerns of abstraction – this statement also captures the layered realism of Hendricks’s figurative canvases. Indeed, when first encountering Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 (Tate L02979; fig.1), the viewer’s response could be drawn from all three of these standpoints. The sitter, George Jules Taylor (born Jules Easton Taylor and referred to by Hendricks as ‘Jules’), relaxes unclothed on a white camel back sofa. His smooth oval head, with face outlined by a sharply trimmed beard, rests against the wooden frame as it curves over the soft white upholstery. With his chin raised, Jules holds a hash pipe in his right hand. He looks directly in front of him through small rimless glasses, his gaze perhaps beckoning the viewer closer and daring them to look.

Although we are presented with Jules’s lithe, taut, naked body, it his charisma that draws us in. With his tilted head, the light reflecting from his glasses and the carefully angled pipe, his nonchalant coolness seems to emanate from somewhere deep inside, making his nudity seem almost unremarkable. It is clear from this portrait that a psychological connection exists between sitter and artist, and that Jules allows Hendricks, and the viewer, to approach. He is at once dramatically sensual – an effect heightened by the interplay of colour, pattern and texture – and elegantly regal, coolly balanced across the heavy wooden seat. His impressive physicality is heightened by the composition that underscores his quiet self-confidence and his unique and flamboyant personality.

Depicting Jules

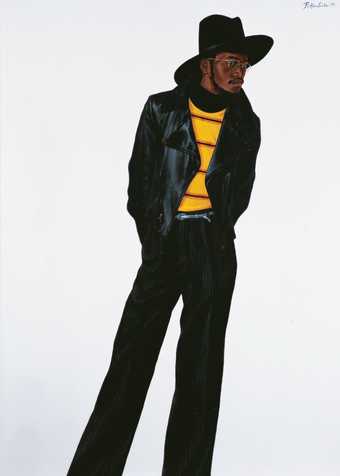

Fig.2

Barkley L. Hendricks

George Jules Taylor 1972

Oil and acrylic on cotton canvas

2323 x 1530 mm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Fig.3

Barkley L. Hendricks

New Orleans Niggah 1973

Oil and acrylic on canvas

1905 x 1321 mm

National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Hendricks painted Jules during his first year in New Haven, while he was studying for his MFA at the Yale School of Art. Jules was an undergraduate student and the pair met in a class run by the painter Bernard Chaet. Their friendship would last until Jules’s death in 1984.2 Hendricks’s first depiction of Jules was a half-length study (Jules 1971, private collection) and a year later he created George Jules Taylor 1972 (fig.2), in which he captured his sitter’s sartorial splendour and distinctive personality. His third painting of Jules, New Orleans Niggah 1973 (fig.3), is a bold study of contrasts which, like Family Jules, explores the effects of black skin against a white background, and the intersections of race and sexuality at a time when deviations from the masculine heterosexual norm were frowned upon, if not risky. Family Jules is the final of the four paintings Hendricks made of Jules. Without sartorial accessories, Family Jules re-enacts something in a similar vein to New Orleans Niggah: the forceful performance of uninhibited racial and sexual identity. Along with New Orleans Niggah it was completed in the artist’s studio in New London, Connecticut, after he had graduated from Yale and taken up a teaching position at Connecticut College. Between its completion in 1974 and its acquisition by Tate in 2015, Family Jules was shown at Connecticut College, New London, in 1978, at the Craftery Gallery, Hartford, in 1979, at the ACA Galleries in New York multiple times between 1980 and 2005, and in the exhibition The Barkley L. Hendricks Experience at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum in New London in 2000.3

Hendricks enjoyed Jules’s fashion sensibility, intellect and sense of humour: the title New Orleans Niggah, for example, directly references an epithet that Jules created for himself while making fun of Hendricks’s passion for jazz music.4 Each of these aspects of Jules’s character are on display in Family Jules. From his confidence to the detail of the background, the painting presents a carefully staged yet highly personalised enactment of the self. As the final of the four portraits the connection shared by Jules and Hendricks emerges, with the assuredness of the sitter matched by the technical bravado of the painter. A painting that began from the traditional studio method, in its final form Family Jules incorporates elements of photography – Hendricks’s other medium of choice – in the patterned tiles lining the back wall and the ornamental edging of the rug, which he copied from photographs taken during trips to Morocco and in museums in Philadelphia. The inclusion of these patterned surfaces sets Family Jules apart from many of Hendricks’s large-scale portraits, such as Lawdy Mama 1969 (Studio Museum in Harlem, New York) and Misc Tyrone (Tyrone Smith) 1976 (private collection), in which striking women and men face out from monochrome backgrounds. Nevertheless, with its emotional power and Jules’s arresting gaze, this painting is illustrative of the style of portraiture for which Hendricks has become known. As others have noted, Family Jules is particularly unique because it straddles two very different genres: that of the traditional art historical nude and that of portraiture. Furthermore, like most of his paintings it is as much a formalist exercise – addressing the relationships of colour, space and flatness – as it is a portrait remarkable for its depiction of a subject.5

Family Jules can be seen as marking a transitional moment in Hendricks’s oeuvre: a culmination of his academic training and a signalling of the career – and concerns – that lay ahead. Blending his interest in old master techniques and his fascination with conditions of flatness and the materiality of surface, it is a painting that is wholly of its time, yet also timeless. To focus on the multiple layers of this work requires shifting between various historical approaches that draw on contemporaneous debates – in the United States and the black diaspora – around race and subjectivity, as well as questions being raised within art history itself. Painted in 1974 in the aftermath of the civil rights era, at the height of 1970s activism and amid debates within the art world about the value of realism, its subject – a black, male nude – certainly pushes it beyond the frame of the representational, racial and gendered conventions of its time. Historiographically, Hendricks’s exploration of the male nude – not uncommon, but certainly still an unusual subject in Western art history – positions Family Jules alongside other reappraisals of the genre by feminist artists such as Sylvia Sleigh that were taking place in this period. Furthermore, his portrayal of black people (who, notably, were not the only subjects of his paintings), also underrepresented in the Western art canon, emerges alongside other efforts in the United States to challenge this marginalisation and demand equality and inclusion for black artists. Scholarly research projects such as the Texas-based Menil Foundation’s The Image of the Black in Western Art, launched in 1960 and ongoing, aim to systematically investigate the ways that people of African descent have been perceived and represented in art over nearly 5000 years. Amassing a huge archive for aesthetic and scholarly study, The Image of the Black in Western Art was initiated in direct response to the effects of segregation in the United States. Meanwhile, other artist collectives and activists challenged the ethos of cultural and public art institutions, where black art and artists remained underrepresented, seeking greater inclusion.6

A painting like Family Jules may seem to focus self-evidently on black identity – a reading that has often been used to oversimplify Hendricks’s complex portraits. But like many of the artist’s paintings it exists outside the boundaries of convention and sits between multiple artistic and historical contexts. In its colour and composition this portrait, like many of Hendricks’s other paintings, certainly encapsulates the spirit and style of 1970s black cultural movements – that ‘awesome expressiveness’ cited by the Chicago-based African American art collective AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists).7 Yet Hendricks’s artistic practice took him, geographically and philosophically, in a different direction from that of the political aesthetics of the black arts movement. Similarly, his interest in surface, flatness and the figure position him in interesting ways in relation to abstraction, pop art and photorealism, although the final effect is very different from each of these styles. Even in its emphasis on figuration, Family Jules still negotiates some of the complex intersections between abstraction and representation that permeated contemporaneous debates, and that are reflected in current scholarship of the period. This is all to say that Hendricks is an artist whose work is very much in dialogue with wider artistic and political debates, but is not necessarily embedded in them. While his work was, and still is, an intervention, challenging social and historical narratives around race, national identity and constructions of blackness, his portraits – as Family Jules so vividly illustrates – luxuriate in the possibilities of artistic experimentation, in following a work’s formal and compositional challenges and in exploring the possibilities of the medium.

Collaborative self-construction

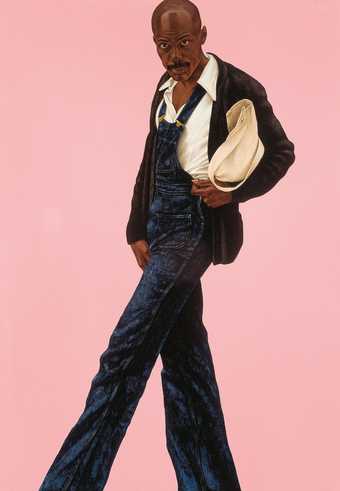

Fig.4

Barkley L. Hendricks

Misc Tyrone (Tyrone Smith) 1976

Collection of Reggie Smith

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

While painting a black subject might have been innovative in the 1960s and 1970s, Hendricks took his cues from his sitters in framing his aesthetic innovations. Hendricks’s understanding of portraiture was not as a form of mimetic interpretation but as a process of identity creation, enacted collaboratively through the performance of a sitter and its interpretation by an artist. What a portrait can express about an individual is not some inherent character or subjectivity that exists separately to what is being represented; rather, identity for Hendricks is a process of (ongoing) production.8 This should not surprise us given his clear interest in the subject of individual self-fashioning and urban style: fashioning a sense of self, experimenting with a language of expression and articulating this narrative requires – in Hendricks’s own words – an understanding of how ‘we react to the world as visual human beings’.9 His Misc Tyrone (Tyrone Smith) 1976 (fig.4), for example, is a portrait of a long-legged man in overalls carrying a cloth bag under his left arm. Dressed in blue and white, Tyrone is striding across the pink background and has turned to look directly out at the viewer. His hands rest against the deep blue denim and his face is calm. His raised eyebrows – like Jules’s tilted head – rather dramatically signal Tyrone’s awareness of our presence. Yet as Hendricks describes it, the theatricality of this painting also reflects Tyrone’s own street ‘performance’ of simply walking along Broad Street in central Philadelphia: ‘we’re on a street in Philadelphia and he was coming towards me … so I asked can I photograph you, and he said yeah. So we’re out there in the middle of center city … and I guess I took about maybe fifteen shots of him and he went through all kinds of different poses … No one crossed in front of us, they all kind of went around and when we stopped and shook hands we got an applause from the people in the street.’10 As Hendricks indicates here, his paintings are inspired by the visual facility of his subjects – friends, lovers, relatives, strangers – who required from him a corresponding visual vocabulary.

It is this collaborative act that underpins Hendricks’s form of portraiture and its emphasis on self-creation, both of which permeate Family Jules. Yet Hendricks approaches the performativity of portraiture slightly differently in this work, in that the painting functions as both a portrait and a nude. Traditionally in art history both genres revolve around a certain kind of idealisation and an assumption of authenticity: the ideal depiction of the essence of a subject or form. Family Jules in its composition and subject matter moves between more canonical art historical genealogies while also occupying a significant place amid debates around abstraction and figuration that remain central to scholarship about the period. It also raises important questions about the intersections of race, gender and sexuality in a complex sociopolitical period. Following a discussion of the making of Family Jules and its formal and stylistic properties, this In Focus will show how this painting brings together Hendricks’s interests in self-presentation and urban street style, along with the aesthetic formulations of the nude and the portrait, to reconfigure and revise their significance in the context of a renewed interrogation of self, identity and collective organisation in the 1970s.

It should be highlighted here that since the act of painting portraits was a dialogue of sorts for Hendricks, this In Focus is structured, in part, around Hendricks’s own words and memories of knowing and painting Jules. A substantial and previously unpublished personal interview with Hendricks, conducted by the author in August 2016 in New Haven, Connecticut, is central to the project, forming primary research material in order to enrich the account of Family Jules. The artist’s comments and insights provide another perspective through which we can read the painting – although no interpretations given in this In Focus should be taken as the final word. Given the recency of Hendricks’s death at the time of publication – Hendricks passed away on 18 April 2017 in New London, Connecticut – incorporating his voice into this project adds a crucial dimension: it provides a deeper context for our interaction with Family Jules and is invaluable as an archival source for interpreting and analysing the work’s ongoing significance.11

Making Jules

Hendricks’s purposeful disinterest in abstraction – ‘you can’t really look at the world in an abstract fashion and get along well’ – stems in part from his commitment to representing the style of his sitters.12 Self-fashioning is an act of assemblage: an intricate process of combining colours, textures and poses that may borrow from a variety of sources.13 In this sense, Hendricks’s aesthetic of quotation – the ways in which he draws on and reformulates a range of art historical genres, particularly that of portraiture and the nude – owes as much to his subjects as it does to a painterly tradition predicated on displays of technical mastery. In this representational style that he developed in the 1970s Hendricks was also acutely sensitive to the psychological drama of self-creation, a sensitivity that Jules clearly shared. Jules was ‘provocative subject matter for me’, says Hendricks. He recalls that he was like a ‘black Dracula who would float around on campus barefoot’ – a vision he gave expression to in the striking painting George Jules Taylor (fig.2).14

In this painting Jules stands against a sombre metallic grey background. His glasses are slightly off-balance, rhyming with his outstretched bare feet and the hands on his tilted hips. His dark blue, stone-washed denim bell-bottoms and jacket are framed by a voluminous black cape that flares around his arms and into the negative space of the flattened background. Like a bat, Jules is suspended in space, an effect heightened by his moving feet that appear to lift away from the canvas. In George Jules Taylor Hendricks uses the texture and gloss of oil to recreate the dramatic effect of cloth – as material object and psychological cipher. In the grand sweep of the cape the heightened possibilities of shadow take on an emotional intensity that attests both to Jules’s flamboyant personality and a certain vulnerability. The solid black of the cape, like a darkly floating shadow, isolates Jules’s figure against the monochrome background and heightens his immediacy; yet simultaneously, like a curtain dropping at the end of a play, it threatens to close in around the length of his body as if to protect him from prying eyes.

In Family Jules this sense of staging is explored through the physicality of the body; the naked form becomes another kind of expressive material and a site of pleasure, making this painting unique both in Hendricks’s oeuvre and within the genre of the nude, as this In Focus will show. As Hendricks recalls, Jules was tall and lithe: ‘He towered over me’. The artist goes on to explain:

Jules was about six-six, six-eight… I mean, he’s a majestic figure as far as that’s concerned, and I wanted that. I’m five-nine, and [when painting George Jules Taylor] I had to use a five-gallon bucket of paint to keep jumping on it to get the right proportions … He was unashamed of his body, and knew that I appreciated it. It wasn’t anything sexual. It’s just he had a wonderful, as I said, physique.15

Fig.5

Marie-Guillemine Benoist

Portrait of a Negress 1800

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Hendricks wanted to find a way of representing his ‘Watusi-like’ body – a now-dated collective name for the Tutsi peoples of Rwanda and a term Hendricks uses to describe Jules’s physicality. Since Jules was a friend and a regular visitor to Hendricks’s studio, they had discussed the possibility of a nude portrait on earlier occasions. On the day Jules came in to sit for the painting, Hendricks remembers draping a white sheet over an old sofa (neither of which are actually depicted in the painting) on which Jules settled into a pose that felt most comfortable to him. Hendricks says: ‘I told him to get comfortable. [Find a pose] that he would hold for a while. And that’s usually the way that my compositional … situations would come about. If you consented to pose for me, I wanted you to be as comfortable as possible.’16 There was no specific direction from Hendricks in this respect, and it was Jules’s decision to keep his small hash pipe with him. As he prepared the surface of his canvas, Hendricks would have engaged Jules in conversation – his usual method for settling models’ nerves – although by now he had painted Jules several times such that their ‘bromance’, as Hendricks called it, was well established.17 Although they met in New Haven during the city’s political unrest in the early 1970s, according to Hendricks these issues were not part of their conversation, and neither was Jules’s homosexuality. Hendricks recalls that they spoke about art quite often, and Jules gave him a small reproduction of Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Negress 1800 (fig.5) that remained pinned to his studio door until his death. Although Jules was not a jazz fan, Hendricks was, and perhaps there was a record playing in the background as the artist and his model worked.

After working up the canvas, Hendricks sketched Jules using oil paint. In his preparatory sketches, made on the canvas itself, he used oil as if it were watercolour (something he also did with great effect in his small landscapes in the round) and with wet, loose brushstrokes created the outline of a composition. For this painting the outline began with Jules seated in the pose used for the final painting, while the details of the sofa, the red and blue silk shirt featuring a white woman’s face, the tiles and the trim of the rug were all added later. In the following audio, excerpted from the 2016 interview with the artist, Hendricks explains this process:

Barkley L. Hendricks interviewed by Anna Arabindan-Kesson, 25 August 2016

In the painting Jules spreads out on the camel back sofa, and where his body gently sinks into the plush material, shadowed indents mark its contours: the outline of his foot, the curve of his shoulder and the round of his thigh. Where his body emerges from the sofa linear angles mark its movement: from the triangular edge of his bent right leg to the sharp points of his right elbow, underarm and slightly raised shoulder. In this angular arrangement, Jules – half splayed and reclining – is firmly grounded within a triangular composition that is itself anchored by the wide base of the sofa. While traditional nudes such as Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque 1814 (Musée du Louvre, Paris) might lounge or lie down, Jules is installed at the pinnacle of a pyramidal composition. Supported in this manner, Jules’s position – looking out and down at the viewer – is reinforced while his statuesque form is fully accentuated.

Jules’s skin is a rich coffee colour. Along his thin limbs, as if caught by a sudden light, we see flashes of copper and bronze hues, which stand out against the creamy white couch. His elongated torso is layered with burnished umber and sienna flecks, giving him the smooth, polished form of a sculpture rising from a base. The rich texture of the bands of brown and white activate the tiled surfaces above his head, as their cool geometry solidifies the background into a dynamically reflective space. The red, blue and pale yellow of the art nouveau patterned shirt that rests on the leftmost part of the sofa provides a startling contrast to the patterned tiles and the oriental-like border of the rug beneath Jules’s feet.

Ceramics glisten above the vivid sheen of silk. The shirt slips across the hard wooden sofa edge and onto its velvety surface, while a thin edged border of gold, red and blue hints at the plushness of the carpet underfoot. Simulating the effect of different materials, Hendricks builds up an added illusion of depth, ironically, through the foregrounding of surface. This sheen effect is heightened by the reflections in Jules’s glasses, which reveal a small source of light shining in from his right. In response, subtle shadows work their way across the tiles, outlining Jules’s rounded head and the curvature of his arm. Shadows settle across his body, too: dark bands fall along and under his right thigh, across his left arm, over his right arm and into a circular shape on his torso. Beneath the left side of his body, a shaded outline draws him further back and down, into the protective embrace of the sofa. Jules seems to both emerge and retreat from the recesses of his support, replicating the guarded theatricality seen in George Jules Taylor.18

Jules’s gaze is unflinching, softened only by the flecks of light in his glasses. In this negotiation of sightlines between subject and viewer, a question of recognition also emerges. As is shown elsewhere in this In Focus, Hendricks drops clues, making references and suggestive allusions.19 Like the wordplay in the title – a pun on ‘the family jewels’, a nickname for male genitalia – the painting is also an exercise in decoding layers of meaning. Hendricks’s commitment to representational painting – especially to the figure – compels us to navigate between multiple frames of reference. This is particularly true of Family Jules, where it is possible to trace these intersecting influences by working through the aesthetic quotations and stylistic homages that he inserts into the frame: Hendricks’s modelling of form through the contrasting elements of colour creates a linear clarity that recalls the smooth precision of a painting by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441); the intense tonality he uses to create emotional depth is reminiscent of the evocative chiaroscuro of Caravaggio (1571–1610). This process is also an exercise in calibration that eventually forces us to consider the process of recognition itself – how someone comes into view, how they become recognisable and, finally and perhaps most provocatively, how we can begin to recognise ourselves reflected in them.