City Visions: The Urban Scene in Camden Town Group and Ashcan School Painting

David Peters Corbett

Like Camden Town painters, the artists of the Ashcan School in early twentieth-century New York depicted scenes of everyday life. While highlighting how both groups were praised for finding beauty in the bleak realities of urban society, David Peters Corbett points to the darker aspects of their vision of the city.

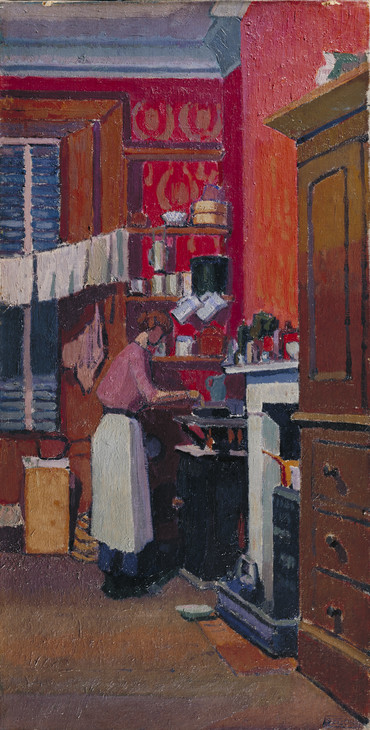

Writing in 1911, the critic of the Illustrated London News observed that Spencer Gore, despite his determination to depict the grimy, everyday world of the modern city and his declared resistance to the ‘æsthetic endeavour’ to ensure ‘actual beauty of shape and material in daily things’, nevertheless ‘still paints with a rare sense of beauty’.

The critic was thus unpersuaded by Gore’s Camden Town assertion that the purpose of modern painting was to record the realities of contemporary life, no matter how bleak these might be and no matter how they might run counter to the canons of good taste and decorum that painting had inherited from its patrician past. Gore’s modernistic demand for grim realism ‘only postpones the moment of capitulation’, wrote the critic: ‘he cries “away with fair and comely sights,” and yields to the fairness and comeliness that is to be found even in a Camden Town bed-sitting-room’ (fig.1).1

This view of Gore and of Camden Town painting in general was widely shared. The reviewer of the Morning Leader, for instance, thought Gore ‘makes one see beauty where one never expected it’;2 and in his obituary of Gore the important art critic Frank Rutter spoke of the painter’s ability ‘to find beauty in the commonplace and romance in the familiar’, so that ‘seen through his poetic temperament even a red-brick suburban villa was transfigured, the streets of Camden Town were touched with loveliness and music-halls were turned into visions of paradisiac refinement’ (fig.2).3

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Gas Cooker 1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 730 x 368 mm; frame: 898 x 556 x 63 mm

Tate T00496

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1962

Fig.1

Spencer Gore

The Gas Cooker 1913

Tate T00496

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond 1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 559 x 686 mm

Tate N03558

Presented by subscribers 1920

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond 1913

Tate N03558

In the spirit of a very similar reading, a 2007 exhibition of the Ashcan School artists – American contemporaries of the Camden Town Group whose major subject was Manhattan and the vivid life of the streets in early twentieth-century New York City – was entitled Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush with Leisure, 1895–1925.4 The first line of the text in the accompanying catalogue refers to the Ashcan artists’ works as ‘the celebration of leisure’, and the essays it presents explore the celebratory attitude they detect in Ashcan art to the modern life and lives of urban America. Earlier scholarship on this important moment in American modernism also saw a fascinated commemoration of the ‘greatest theatre in New York ... the theatre of its streets’ as central to the Ashcanners’ achievement, and wrote with enthusiasm of the commemoration of ordinary lives and subjects in their depiction of working class streets and apartments.5 John Sloan, Everett Shin, George Bellows, George Luks and Robert Henri, the senior artist whose views influenced all the others with his insistence that artists should go to the realities of American life to find their subject matter, stepped aside from the polished academic style taught in art schools of the time and developed a gritty, urgent manner that sought to catch the ebb and flow of life in urban America, and above all in New York City, then a world metropolis second only to London.

This essay aims to explore the nature of this perceived transformation of the grubby or sordid realities of modern city life into something new and strange, both beautified and acknowledged as worthy of celebration, in the Camden Town Group’s work. This process is what Walter Sickert, when in 1889 he introduced the group of painters he called the ‘London Impressionists’, had spoken of as ‘the magic and poetry’ of London, ‘the most wonderful and complex city in the world’.6 That lyrical evocation of the metropolis as a place where metamorphosis could be observed, transforming the ‘sordid or superficial details’ of reality into ‘magic and poetry’, helps us to see the achievement of both Camden Town and their American contemporaries.7 In neither case, however, is that the whole story.

In order to explore the transformative energies of Camden Town art I shall bring Camden Town artists together with the Ashcanners, whose New York was ‘both coarse and inspiring’ and emerged as the ‘city that would define urban life in America’ for the whole of the subsequent ‘American Century’.8 I shall also offer some comparisons between the modernists who succeeded these two groups of realists in both Britain and America and explore how their radical revisionism of visual norms and accepted schemes of representation can help us understand the Camden Town painters’ earlier attempts to characterise the modern city. The work of Charles Sheeler in 1920s New York and the vorticists in pre-First World War London casts a powerful illumination on the range and nature of the Camden Town artists’ achievement. Their interest in the systems and structures of the city allows us to see how focused the American realists were on the city’s inhabitants as the main tool for their diagnosis of the nature of modern life, and also encourages us to perceive that Camden Town painting is different from these contemporary images, harsher and in some ways more radical. In this way the essay will deal with both the contrasts and the similarities to be gleaned from the comparison of British and American realists at this crucial juncture for both countries in the development of an art of the cities and the newly modern lives lived within them in the early twentieth century.

*

As the critics’ comments with which I began suggest, Camden Town painting responds to the visual possibilities of painting as fiction, a construction that orders and composes the world within the medium of painting itself and which is as fully concerned with what Sickert had called in 1889 the evocation of ‘emotion induced by the complex phenomena of vision’ as with the realism of the scene depicted.9 In his obituary of Gore, published after the latter’s early death in 1914, Sickert summed up what he believed Gore had achieved in terms revealingly close to these:

it is not only out of scenes obviously beautiful in themselves, and of delightful suggestion, that the modern painter can conjure a panel of encrusted enamel. ... A scene, the dreariness and hopelessness of which would strike terror into most of us, was to him matter for lyrical and exhilarated improvisation. I have a picture by him of a place that looks like hell, with a distant iron bridge in the middle distance, and a bad classic façade like the façade of a kinema, and two new municipal trees like brooms, and the stiff curve of a new pavement in front, on which stalks and looms a lout in a lounge suit. The artist is he who can take a piece of flint and wring out of it drops of attar of roses.10

With the exception of that wonderful ‘lout in a lounge suit’, who is anyway no more than a generic urban type, Sickert emphasises the architectural environment over the human and evokes a real sense of the way in which the physical city begins to move and stir into life as an active agent in Gore’s pictures (fig.3). But he also rightly emphasises the fictionality of the description, not only by implication through the rhetoric of his own elaborate and highly wrought prose, but by stressing that ‘panel of encrusted enamel’. Gore’s painting is a representation, a conjuring of beauty out of the apparently sterile and rebarbative environments of the modern city. It is a position Sickert had adopted in 1889, asserting Edgar Allan Poe’s quest for ‘beauty’ over any imperative to ‘make intensely real and solid the sordid or superficial details’ of the scene.11 This sets up a dialogue between the realistic and the painterly, between the accidental qualities of observed life and the structuring framework of the composition, and between the observed scene and the character of its representation. It suggests that a truly modern painting as the Camden Town artists interpreted it might be an art of formal intensity and erudition. ‘The attempt to separate the decorative side of painting from the naturalistic seems to me to be a mistake’, wrote Gore, reviewing Roger Fry’s first post-impressionist exhibition in 1910. If he went on to assert that, ‘Simplification ... may be done to produce a greater truth to nature as well as for decorative effect’ that was a way of claiming truthfulness for the formal side of painting rather than deprecating it.12 Both the reality of the scene – that ‘truth to nature’ Gore thought so important – and the statement that the formal or ‘decorative side of painting’ is inseparably involved with any attempt to realise it on the canvas, are fundamental aspects of Camden Town’s conversation with itself about the necessity and practice of a true modern art. This dialogue is central to the Camden Town Group’s response to the modern and how it saturates the city, the countryside and the spectrum of semi-urban places in between in ways that call for novel representation to communicate in visual form.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Houghton Place 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 515 x 614 mm

Tate N03839

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1927

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Houghton Place 1912

Tate N03839

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

St James's Park 1912

Oil paint on canvas

725 x 900 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.4

Malcolm Drummond

St James's Park 1912

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

It is a dialogue which can be observed in many of the Camden Town works that deal with the metropolis of London. Malcolm Drummond’s St James’s Park 1912 (fig.4) takes on a profoundly urban scene and asserts its truthful nature as an account of modern experience, but transforms it in the treatment it receives on the canvas. The art historian Wendy Baron justly observes of this painting that it balances ‘poetry and prose’, the rigid construction enforced by the perspective providing a structure within which the artist ‘set free his poetic imagination’ to represent the subject ‘in a range of rich, unrealistic, confectionary tints’.13 A mundane London scene, realistic and even naturalistic in its selection and character, is set against the capacity of painting to transform that scene by the power of its representation. In Drummond’s hands London becomes not only a city of the everyday but also a place of imagination, creativity and playfulness.

Despite the almost childlike quality of Drummond’s colour, there is also a darker aspect to his vision, and Baron is right to associate the effect the painting produces with one of the great moments of nineteenth-century painterly attempts to capture the subtleties of the new relationships with the world generated by the metropolis, Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 1884–6 (The Art Institute of Chicago).14 Drummond’s painting has something of the hieratic and processional quality that Seurat gave his study of promenading Sunday Parisians. But it is also more playful than Seurat’s rigidly stylised account of urban leisure, and one might see this playfulness as an indication that the painting is partly about the pleasure available to its denizens in the metropolis. But even if Drummond’s depiction of moments of release and enjoyment in London has a celebratory element to it, his figures also possess the mechanical gait and jerky, automatic action that many modernists attributed to the citizens of their highly industrialised societies. The positioning of feet and hands, particularly of the small child to the left and the pill-box wearing soldier who balances the child and its nurse on the right, suggest puppetry and the shuddering movements of wooden limbs on strings. Like Seurat’s figures, these Londoners are rigid, awkward and made over into the visual style and character of their environment. Their pleasure is ‘vitiated’, as the art historian Stephen Eisenman has written of the effects of Seurat’s painting, by the unbending geometry of industrial urban life.15

This opposition is a central modernist concern. Is this the city as disciplined and geometrical, the city that subordinates the interests of the individual to its greater vitality and force? Or is it the city as space of leisure and relaxation? Drummond declines to come down firmly on either side of this opposition; or rather he seeks to deny that they are fruitfully opposed. To put the two into productive relation, he maintains the right of imagination to insert itself into the grimly mundane, and celebrates its capacity to transform, to render as joy or play what might at first appear to be some alienated scene of isolation populated by jerky marionettes. We are left balanced on the cusp: the scene is disturbing, but also childlike, even wondering, and we are invited to work to make sense of that modern duality.

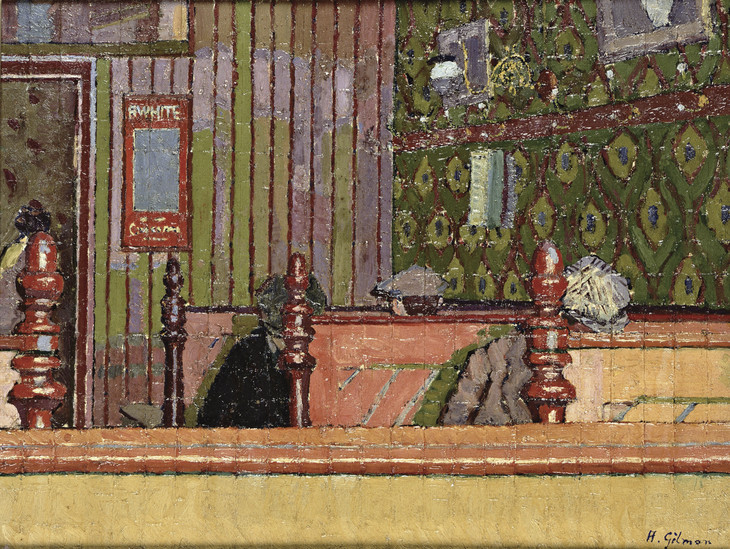

Although it describes them in an abstracted and stylised format, Drummond’s painting presents us with quite a large group of people. Another of the striking characteristics of Camden Town city painting, however, is the frequent absence of crowds, bustle, or sometimes even evident human actors. The packed, frenetic movement and buzzing crowds of pedestrians familiar from contemporary film clips of the early twentieth century are exactly what most Camden Town painting forbears to represent. Charles Ginner’s Piccadilly Circus of 1912 (Tate T03096, fig.5) is an exception, although even this canvas explicitly rejects the representation of movement (for which there were existing painterly conventions) in favour of Ginner’s ‘good eye for intricate arrangement’ in pattern and design.16 Instead of bustle and dynamism, Camden Town painters often saw the city as virtually empty, marked by monumental compositions emphasising architectural mass and form, as in Ginner’s Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841, fig.6) and Evening, Dieppe of 1911 (private collection).17 This could morph into a harsh ejection of the human actors from the scenes they depicted. In Harold Gilman’s An Eating House c.1913–14 (fig.7), the patrons are visible only as detached body parts: a head, crowned with its cap, rising above the edge of the cubicle; half a torso; an anonymous blank face, cut through by the emphatic wooden verticals that define the ends of the booths. Further forward a cap and coat seem to dangle, ambiguously neither inhabited nor empty. The human here is of much less importance than its context. The slicing but shallow diagonal and unexpected colour of the booth from which we view the room, like the contrasting pinks and greens of the wallpaper and the woodwork, are stronger presences than the men hunched over their food and drink.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 664 x 461 mm; frame: 788 x 590 x 50 mm

Tate T03841

Purchased 1984

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.6

Charles Ginner

Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912

Tate T03841

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.7

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

This same neglect of the human spaces of the city can be observed in Ginner’s The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station of 1913 (fig.8) and Gore’s Mornington Crescent 1911 (fig.9). In both paintings the human scale is abandoned for an aerial viewpoint, the concentration on the rhythms of the roofscape and the arresting bulk of the buildings overpowering the scale of the few, rather aimless, people depicted. Ginner deliberately makes the figures in Sunlit Square virtually identical to the street bollards and insists on their rhythm as a series, pairing them with the series of roofs above in a device which effectively places them in the same category of urban objects. This evocation of the scale and presence of the city may derive in part from Sickert’s paintings of the 1880s and 1890s, in which Dieppe, Venice or London become the dominant presences in a haunting visual play of light and volume.18 As in these earlier Sickerts, the city itself is often the major protagonist in Camden Town works. Gore’s painting is one of a series in which he worked and reworked the scabrous façades and shabby gardens of Mornington Crescent to produce what Sickert called ‘a microcosm of the house of life’, although it is the absence of emphasised human activity that is striking.19 In the process, one aspect of what happens is the diminution of the human scale and its replacement by the organised, abstract and patterned motif of the city itself, the city as system and entity, looming into our attention like the raw jerry-built architecture which surrounds Sickert’s abstract ‘lout in a lounge suit’ and suppressing the individuality of its dwindling inhabitants.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Oil paint on canvas

43 x 51 cm

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

Fig.8

Charles Ginner

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Mornington Crescent 1911

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 616 mm

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Fig.9

Spencer Gore

Mornington Crescent 1911

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

If we turn to the contemporaneous imagery produced by the Ashcan School painters, this aspect of Camden Town city painting is thrown into still sharper relief. The mainstream of Ashcan art, its subjects drawn from the streets and dives of the New York cityscape, offers an intimate, sanguine feeling for the pungent, immediate pressure of humanity in the mass, for the crowd and its attributes of low genre or burlesque.20 Such interests underpin much of Ashcan work and on the whole commentators on the Ashcanners have chosen to emphasise these aspects of their art which reflect the lively, diverse and energetic character of New York. Taking their cue from these readings and from the bustling density of human presence in Ashcan images, art historians have seen the Ashcanners as the visual equivalent of Walt Whitman, poets of the humanity and dynamism of the streets and of ‘urban realism’, defined as the registration of those qualities. Their pictures are understood as humane depictions of everyman, evocative observations of ordinary humankind in such a way that we can all identify with that ordinariness.

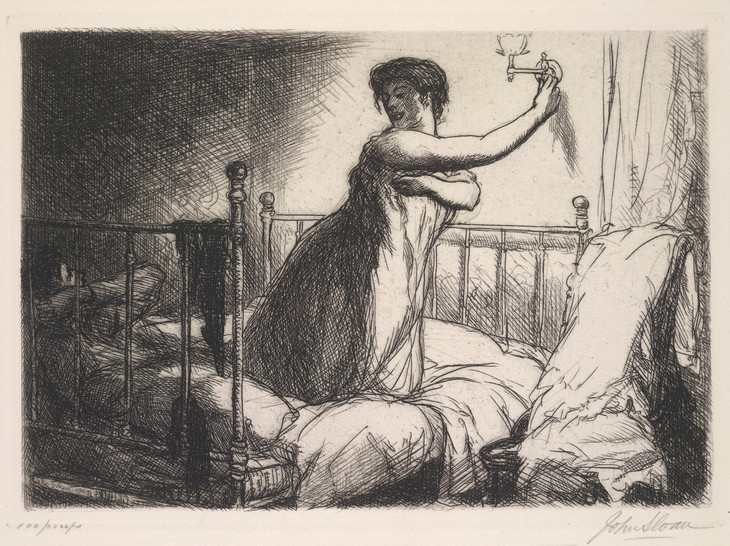

In the Ashcan artist John Sloan’s Turning Out the Light of 1905 (fig.10), we see the interior of a dowdy apartment. Sloan’s etching does a good job of presenting a woman whose attention is all on the expectation of imminent pleasure, and who efficiently but also sensually prepares to enjoy it. The tableau is presented close up against the picture plane so that we are made to feel almost as if we are inside the room ourselves. The woman, kneeling on a double bed that occupies more than half the space, abstractedly rotates the tap of the gas bracket with her right hand while she turns away. The contrapposto allows the outlines of her right hip and thigh to show through the fabric of her nightdress. We see her luxurious enjoyment of the prospect to come. With her left arm the woman reaches across her body in a way that suggests she is releasing the garment, and, following the gesture, we realise why her attention is elsewhere: she glances down towards the bed where we can make out a waiting man, his hands crossed behind his head and his face angled upwards towards his companion. The small size and shabbiness of the room are emphasised by the stockings and other clothes thrown over the bed frame and chair, and by the exposed mattress that pushes towards us out of the picture’s recession. Much of the space to the left is dark and vanishes away into depths which stand for both the intimacy the couple is about to enjoy and the otherness of people we observe to understand the facts of life in the new cities. A comparison with Sickert’s The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? c.1908 (fig.11) highlights the compassion of Sloan’s picture and the emotional ambiguity of Sickert’s. Whereas the American artist offers us an image of a common human act, Sickert’s distraught or perhaps merely bored couple suggests a number of darker readings without clarifying the nature of the relationship.

John Sloan 1871–1951

Turning Out the Light 1905

Etching on paper

125 x 175 mm

British Museum, London

© Estate of John Sloan. ARS, NY / DACS, London, 2010

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.10

John Sloan

Turning Out the Light 1905

British Museum, London

© Estate of John Sloan. ARS, NY / DACS, London, 2010

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? c.1908

Oil paint on canvas

256 x 356 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund B1979.37.1

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.11

Walter Richard Sickert

The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? c.1908

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund B1979.37.1

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Sloan’s etching appeared in a series called New York City Life, and its subject matter is echoed in his other scenes of the metropolis featuring working class entertainment and pleasure. This interest in the bustle and vigour of urban life is common, too, to Sloan’s fellow Ashcanner, George Bellows. But in Bellows’s hands this depiction of the metropolis can take on a different and ferocious aspect.

George Bellows 1882–1925

Stag at Sharkey's 1909

Oil paint on canvas

920 x 1226 mm

The Cleveland Museum of Art. Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection 1133.1922

Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art

Fig.12

George Bellows

Stag at Sharkey's 1909

The Cleveland Museum of Art. Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection 1133.1922

Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art

In these American images, the crowd, the fertile density of humanity, effectively becomes the city and serves as its primary imagery and visual definition. Ashcanners rarely turn their gaze up from the tunnels and sweeping perspectives of the streets.23 When they do, it is most often to gaze down into the maelstrom of human lives that such a perspective reveals to them.24 This dependence on humanity, whether en masse or individually, to structure their understanding of the urban environment gives Ashcan painting a particular interest in empathy, often as a means of asserting the unity of spectator and other urban dwellers the artist depicts,25 but also as a means of forcing the spectator into contact with more rebarbative urban realities.26 Sloan wrote of how ‘the real artist finds beauty in common things’, phraseology that suggests lines of thinking similar to those propounded by Sickert. But unlike Sickert and the Camden Town painters Sloan’s view of art is that it serves as compensation for the lives of the masses and the dwellers in urban poverty. ‘I believe the work of artists ... is a kind of food for starving souls’, he wrote, meaning that he thought it capable of ameliorating the sufferings of the world through the depiction of the richness of observed and experienced life.27

John Sloan 1871–1951

Movie, Five Cents 1907

Oil paint on canvas

597 x 800 mm

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of John Sloan. ARS, NY / DACS, London, 2011

Photo © Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, J0026828

Fig.13

John Sloan

Movie, Five Cents 1907

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of John Sloan. ARS, NY / DACS, London, 2011

Photo © Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum, J0026828

Compare this depiction of a new urban entertainment to Drummond’s In the Cinema 1913 (fig.14). In Drummond’s painting the audience appears more socially coherent and the emotional reaction, which in the Sloan is openly shared, is given a memorable image of separateness and isolation in the constrained but expressive figure of the man whose hand seems raised in an involuntary excitement he immediately inhibits and reserves for himself. In Sloan’s Movies,5 Cents we are invited into the community by the frank glance of one of the women. No one hails us in the Drummond, which seems far more a picture about the separateness of individuals in the city.

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

In the Cinema 1913

695 x 695 mm

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

Fig.14

Malcolm Drummond

In the Cinema 1913

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.15

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

It is true that this depiction of isolation and inwardness seems a far cry from the gawping cluster of music-hall patrons Sickert depicted in Noctes Ambrosianae 1906 (fig.15), but there we have a demonised version of the crowd, as if the communal suggests a sort of frenetic energy or virulent alien life. There is no empathy that the spectator can easily summon up for these grotesque faces and awkward gestures of pleasure and urgent release. It is distinct, too, from Gore’s The Balcony at the Alhambra of c.1911–12 (York Art Gallery),29 which takes a more relaxed view of both pleasure and the audience’s appreciation of a communal spectacle. In the Cinema, however, represents a more important aspect of the Camden Town view of the city. In its depiction of social constraint, distance and submission it is another of their versions of the metropolis as a place where individuals are subject to the palpable pressures of modern technology and the organisation and systematisation of the modern urban environment, and where they are shrunk to a diminished scale.

In contrast to the often empty streets and their lessened inhabitants, Camden Town painting depicts urban dwellers most readily in interiors, as is evident in the many portraits set indoors. In many ways it is these works featuring individuals or occasionally couples in grubby north London bedsits or undistinguished living rooms that approach most closely the more familiar modernist assessment of contemporary urban life. There is an alienated quality to Gore’s portrait of his wife (Tate T03561), Gilman’s sallow and depressive Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15 (fig.16), and Sickert’s study of marital troubles, Off to the Pub 1911 (Tate N05430), that speaks directly to a sense that urban life is melancholy, burdensome and doom-laden. Like Gore’s North London Girl c.1911–12 (Tate T00027, fig.17), these figures are living a complex life within the material world of wallpaper, teacups, mantelpieces and beer glasses. These are images of the other, the isolated self, caught up in a private drama, or preoccupied with unknowable experience amidst the clutter of modern urban living.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Oil on canvas

460 x 610 mm

Private collection

Fig.16

Harold Gilman

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Private collection

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

North London Girl c.1911–12

Oil paint on canvas

support: 762 x 610 mm; frame: 814 x 712 x 102 mm

Tate T00027

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

Fig.17

Spencer Gore

North London Girl c.1911–12

Tate T00027

*

Looking forward only a few years beyond the heyday of the Ashcan artists to the late teens of the twentieth century and in to the 1920s, the photography and painting of the American modernist Charles Sheeler presents the spectator with a more objectified city than his Ashcan predecessors and, importantly, one in which the crowds and human presence so pervasive in Ashcan paintings of the city have entirely vanished. For Sloan, presence can be figured directly in the observers he places in the city.30 But such confidence has not survived in Sheeler. In his photographs taken from atop New York skyscrapers human presence is visible only in temporary imprints that imply the human scale but only by substitution, like the shadow of smoke on the wall in the photographs of New York City he took during the 1920s.

Charles Sheeler 1883–1965

Skyscrapers 1922

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 330 mm

The Phillips Collection

© Estate of Charles Sheeler

Photo courtesy of The Phillips Collection

Fig.18

Charles Sheeler

Skyscrapers 1922

The Phillips Collection

© Estate of Charles Sheeler

Photo courtesy of The Phillips Collection

Such observations might help us understand the implications of the fact that, while the Camden Town painters have their realism in common with the Ashcan School, their depictions of the city also share this quality of absence with Sheeler. Their interests respond to industrialisation as one among the diverse processes of modernisation that Britain inherited in the early twentieth century. Contemporaries described the sense of belittlement that accompanied the huge scale and enormous power of industrial machines.

Edward Wadsworth 1889–1949

The Port circa 1915

Woodcut on paper

image: 187 x 127 mm

Tate P07119

Purchased 1970

© The estate of Edward Wadsworth

Fig.19

Edward Wadsworth

The Port circa 1915

Tate P07119

© The estate of Edward Wadsworth

Lewis’s depictions of the city, as in The Crowd or Workshop c.1914–15 (Tate T01931, fig.21), with its vivid urban forms striking into the single blue orthogonal of the sky, explore the tensions between modern liberation and oppression through the wild urban geometry of skyscrapers and the fleeing workers who are diminished in comparison to their towering scale. In this perception, characteristic as it seems of radical modernism rather than of the preceding perceptions of realism, the vorticists are perhaps indebted to the Camden Town Group’s imagery. Lewis was himself a temporary member of the Group, but his ‘advanced’ radicalism speedily found itself out of temper with its surroundings. Nevertheless, despite its advanced modernism, Lewis’s The Crowd seems indebted to Drummond’s earlier canvas of St James’s Park (see fig.4). The Crowd’s rigid, automaton-like figures revise the marionettes of St James’s Park, while that picture’s anti-naturalistic colour is transformed into what the art historian Paul Edwards has called the ‘grimy textures and mechanical forms of vorticist abstraction’, the acid, dirty hues favoured by the modernists to convey the mechanised contexts of their world.32 St James’s Park, like Lewis’s later paintings, posits the ambiguity of modern city life, acknowledging its mechanised, alienated qualities at the same time as its opportunities for liberation and pleasure.

Wyndham Lewis 1882–1957

The Crowd ?exhibited 1915

Oil and pencil on canvas

support: 2007 x 1537 mm; frame: 2195 x 1740 x 60 mm

Tate T00689

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1964

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Fig.20

Wyndham Lewis

The Crowd ?exhibited 1915

Tate T00689

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Wyndham Lewis 1882–1957

Workshop circa 1914–5

Oil on canvas

support: 765 x 610 mm; frame: 915 x 760 x 75 mm

Tate T01931

Purchased 1974

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Fig.21

Wyndham Lewis

Workshop circa 1914–5

Tate T01931

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Like Sheeler, the Camden Town artists already perceive this aspect of the world of early twentieth-century modernity. Their empty streets and quizzing of the human scale make the same point: that it is the systems of modern life that are most pressing and that most need to be given a visual expression. Unlike their Ashcan contemporaries they do not see the warm intimacy of the crowd or the possibilities of human sedulity as a means of redemption, or as a sufficiently convincing alternative to the mechanical world around them. It is no surprise perhaps that Lewis published works by Gore in his modernist little magazine Blast (1914) and wrote a powerfully melancholy and admiring obituary of his old friend and sparring partner.

*

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Leeds Market c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 610 mm; frame: 690 x 790 x 75 mm

Tate N04273

Presented by the Very Rev. E. Milner-White 1927

Fig.22

Harold Gilman

Leeds Market c.1913

Tate N04273

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Beanfield, Letchworth 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 305 x 406 mm; frame: 462 x 562 x 57 mm

Tate T01859

Purchased 1974

Fig.23

Spencer Gore

The Beanfield, Letchworth 1912

Tate T01859

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth Station 1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Fig.24

Spencer Gore

Letchworth Station 1912

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

But, as I am suggesting, this aspect of Camden Town may not be at all at odds with perceptions of the city. It in fact displays an understanding of modern life that is closer to modernism in its more radically revisionist forms of a few years later than it is to contemporary urban realists like the Ashcanners. Intriguingly, among the most formally experimental of Camden Town works are depictions of rural scenes or the new Garden Cities like Letchworth that occupied an intermediate state between town and country without fully belonging to either. Gore’s The Beanfield, Letchworth of 1912 (Tate T01859, fig.23), with its zigzag description of the ploughed field in the foreground, The Icknield Way 1912 (Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney),35 in which a jagged track of acid green plunges towards the sunset jigsaw of rhomboid clouds, and the flattened sky and patterned surface of The Cinder Path (Tate T01960) of the same year, are significant examples of this interest in making strange the experience of the landscape; while William Ratcliffe’s Hampstead Garden Suburb from Willifield Way c.1914 (Tate T12260) and, above all, Gore’s 1912 Letchworth Station (fig.24) bring the city with its infrastructure of roads and railways into the country via a geometric and systematic landscape. This interest in depicting not only the city as the place where modern life is most intense, but also the spectrum of places between the countryside and the urban, is one of the Camden Town Group’s most important achievements. Modern life is recognised in the suburbs as fully as in the metropolis.

However, it would be misleading not to acknowledge aspects of Ashcan painting that relate to novel diagnoses of modern life such as these. Among the Ashcan painters, George Bellows was never only a painter of the city. He travelled in the north-east and mid-west of America, and painted New York’s parks and environs, rural areas like Zion, New Jersey, where he spent time in 1909, and scenes along the Hudson. In 1911 he followed Robert Henri and Henri’s pupil Rockwell Kent to Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine, the coastline where Winslow Homer had painted. There he produced several series over the subsequent few years that take the landscape and the sea as their subject matter without direct reference to the urban.36 There is a tendency to downplay the importance of these works in comparison to the gritty depictions of city life for which the Ashcanners are better known. Bellows’s aestheticised paintings of Monhegan and the Hudson do not fit in with conceptions of urban realism.

George Bellows 1882–1925

The Palisades 1909

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 968 mm

Daniel J. Terra Acquisition Endowment Fund, 1999.10 Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, IL.

Photo Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Fig.25

George Bellows

The Palisades 1909

Daniel J. Terra Acquisition Endowment Fund, 1999.10 Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, IL.

Photo Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Bellows’s 1923 Fisherman’s Family (private collection) produces a forceful reading along these lines from Bruce Robertson. Robertson thinks of the painting as ‘a hybrid work, it awkwardly integrates the past and the future, staking a claim to tradition and modernity’, and concluding that ‘this middle ground’ indicates that Bellows ‘stands tentatively, pulled both ways’.39 But this is an unduly negative way of putting it. We should not imagine some sort of competition between Camden Town, the Ashcanners and the modernists for the palm of most radical or most modern. Instead it is worth observing the ways in which both Camden Town and urban realist painting more widely are perceptive about the nature of life in the most modern cities of their time.

Notes

Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush with Leisure, 1895–1925, exhibition catalogue, Detroit Institute of Arts 2007.

Robert W. Snyder, ‘City in Transition’, in Rebecca Zurier, Robert W. Snyder and Virginia M. Mecklenburg (eds.), Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and their New York, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 1995, p.29. See, for example, John Sloan, Picture Shop Window 1907 (Newark Museum, New Jersey).

Walter Sickert, ‘Preface’, A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London, December 1889, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.60.

Spencer Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’, Art News, 15 December 1910, p.19.

Reproduced in The Art Institute of Chicago, http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/27992 , accessed August 2010.

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (1).

See, for example, The Statue of Duquesne, Dieppe 1902 (Manchester City Art Galleries), reproduced in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992 (31).

See, for example, John Sloan, Election Night 1907 (Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, NY), http://magart.rochester.edu/Obj707?sid=18604&x=341082 , accessed August 2010.

Reproduced at The Phillips Collection, http://www.phillipscollection.org/research/american_art/artwork/Sloan-6OclockWinter.htm , accessed August 2010.

Reproduced at Corcoran Gallery of Art, http://www.corcoran.org/collection/highlights_main_results.asp?ID=61 , accessed August 2010.

See, for example, Robert Henri, Snow in New York 1902 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC), http://www.nga.gov/fcgi-bin/timage_f?object=42929&image=7629&c=gg71 , accessed August 2010.

See, for example, George Luks, Street Scene (Hester Street) 1905 (Brooklyn Museum), http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/609/Street_Scene_Hester_Street , accessed August 2010.

See, for example, George Bellows, Business-men’s Bath 1923 (British Museum) http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectId=698819&partId=1 , accessed August 2010.

John Sloan, The Gist of Art: Principles and Practices Expounded in the Studio (1939), revised edition, London 1977, pp.41, 26.

See, for example, John Sloan, Sunset, West Twenty-Third Street 1906 (Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska), http://www.joslyn.org/collections-and-exhibitions/permanent-collections/american/john-sloan-sunset-west-twenty-third-street-23rd-street-roofs-sunset-/ , accessed February 2012.

Reproduced at National Gallery of Art, Washington, http://www.nga.gov/fcgi-bin/tinfo_f?object=46557 , accessed August 2010.

Reproduced at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, http://www.metmuseum.org/works_of_art/collection_database/all/up_the_hudson_george_bellows/objectview_enlarge.aspx?page=1&sort=0&sortdir=asc&keyword=george%20bellows&fp=1&dd1=0&dd2=0&vw=1&collID=0&OID=210000746&vT=1&hi=0&ov=0 , accessed August 2010.

David Peters Corbett is Professor of Art History and American Studies at the University of East Anglia.

How to cite

David Peters Corbett, ‘City Visions: The Urban Scene in Camden Town Group and Ashcan School Painting’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www