The Psychiatric Sublime

Nicholas Tromans

Traces of sublime rhetoric can be found in the discourse on mental illness in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nicholas Tromans looks to the visual culture of medicine to explore the history of a sublime aesthetic in psychiatry.

In January 1789, during the first madness of King George, Francis Willis, the Lincolnshire mad-doctor treating him, was called to a parliamentary committee to explain his methods which had been reported as being both amateurish and intimidatory. The King had apparently been allowed to use a cut-throat razor to shave himself even during periods of disturbance. One of Willis’s examiners was the Rt. Hon. Edmund Burke, who, we are told,

was ... very severe on this point, and authoritatively and loudly demanded to know, ‘If the royal patient had become outrageous at the moment, what power the Doctor possessed of instantaneously terrifying him into obedience.’ ‘Place the candles between us, Mr. Burke,’ replied the Doctor, in an equally authoritative tone – ‘and I’ll give you an answer. There Sir! by the EYE! I should have looked at him thus, Sir – thus!’ Burke instantaneously averted his head, and, making no reply, evidently acknowledged this basiliskan authority.1

Burke, it seems, was already finding less pleasure than he had once believed there was to be found in the tremors of fear.

Willis’s application of ‘the eye’ to lunatics, and Burke’s assumption that they regularly required ‘terrifying ... into obedience’, were standard features of the eighteenth-century mad-doctor’s therapeutic kit.2 That range of treatments had in fact dramatically shrunk since Elizabethan times. The political, religious and medical élites’ profound aversion to enthusiasm had led to an insistence upon interpretations of mental illnesses that totally eschewed the traditions of demonic possession, and to the rejection of all the astrological and para-magical interventions which were still current in the seventeenth century. Michael Macdonald concluded his famous book on seventeenth-century English psychiatry, Mystical Bedlam, with this assessment: ‘The rise of psychological medicine [during the eighteenth century] has often been represented as a saga of scientific progress. It was not. It was instead a tale of religious hatred, political conflict, social antagonism, and, at last, intellectual advancement.’3 The élite acceptance of a psychological understanding of madness, underwritten by John Locke’s labelling of lunacy as reasoning from wrong premises, opened the way, in the eighteenth century, to a phase of mental doctoring during which the physician felt bound directly to manipulate the patient’s feelings using all the ingenuity they could muster. Lunatics continued to be bled, vomited and purged according to the ancient tradition of the anti-inflammatory regime which would dilute the damaging excesses of their vital fluids.4 But now their minds, too, would be worked upon with comparable interventions, interventions informed by the categories of eighteenth-century psychology, among them the sublime.

Let us recall that the sublime was essentially healthy. The eighteenth-century debates around the aesthetics of transporting sensations were, as Frances Ferguson stressed in her book Solitude and the Sublime, conducted precisely in order to define an appropriate place for the sublime in a shared culture. For Ferguson, later Romantic emphases on uncompromised subjectivity obscured this point until recent theory, especially Deconstruction, reduced the arrogant subject back down to size.5 To be alive to the massive possibilities that seem to exist beyond one’s capacity really to grasp them might be an exercise in existential humility. (And, Burke added in his Enquiry, the sublime offers a sort of work-out for the finer fibres of the nervous system).6 To actually start believing in the possibility of living the sublime was madness. Žižek, paraphrasing Kant, explains that the sublime prompts astonishment, a reasonable enthusiasm, as opposed to the ‘insane visionary delusion that we can immediately see or grasp what lies beyond all bounds of sensibility’.7 Such confusion is conventionally attributed to the mad, but in a political context was attributed also by Burke to the French Revolution, and by Žižek and Lyotard to the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century.8

William Hogarth 1697–1764

Four Prints of an Election, plate 2: Canvassing for Votes, engraved by Charles Grignion 1757, published 1758

Etching and engraving on paper

image: 405 x 537 mm

Tate T01796

Transferred from the reference collection 1973

Fig.1

William Hogarth

Four Prints of an Election, plate 2: Canvassing for Votes, engraved by Charles Grignion 1757, published 1758

Tate T01796

Jacob More c.1740–1793

The Deluge 1787

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1504 x 2046 x 37 mm

Tate T12758

Purchased with assistance from Tate Patrons and Tate Members 2008

Fig.2

Jacob More

The Deluge 1787

Tate T12758

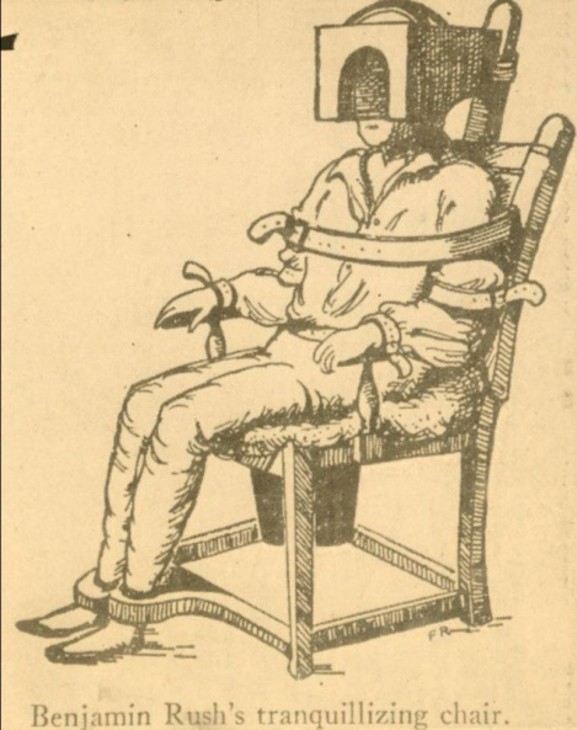

Benjamin Rush

'Tranquillizing' Chair 1811

Engraving in Philadelphia Medical Museum

Photo © University of Pennsylvania Archives

Fig.3

Benjamin Rush

'Tranquillizing' Chair 1811

Engraving in Philadelphia Medical Museum

Photo © University of Pennsylvania Archives

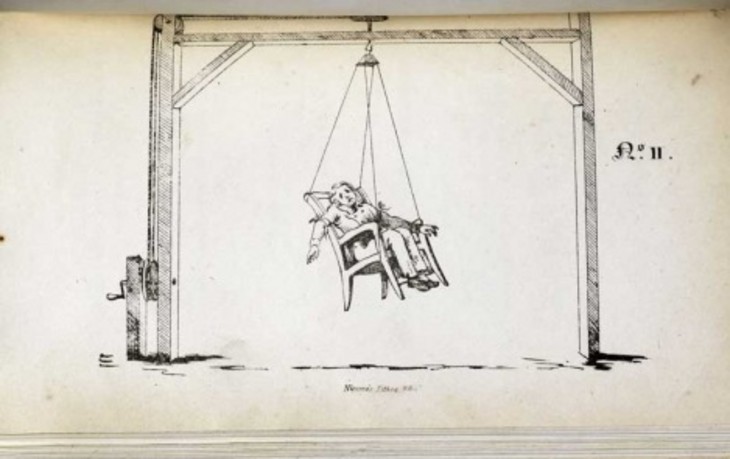

Rotatory Machine From Alexander Morison, Cases of Mental Disease, 1828

By permission of The British Library (1172 H6)

Fig.4

Rotatory Machine From Alexander Morison, Cases of Mental Disease, 1828

By permission of The British Library (1172 H6)

The rotatory chair was particularly advocated by Joseph Mason Cox, who owned a large private asylum near Bristol, and whose Practical Observations on Insanity contains some of the more flamboyant techniques to be recommended in the literature of the period. Cox suggested various elaborations on the use of the swinging chair; for instance, it might be ‘employed in the dark, where, from unusual noises, smells, or other powerful agents, acting forcibly on the senses, its efficacy might be amazingly increased’.13 For patients particularly resistant to such interventions, Cox recommended to the alienist an even more daring strategy. If the patient could not be recalled from his or her world of sublime delusion, then the doctor must go in and get them. This meant acting up to the delusional drama, the doctor assuming a role within it.

It is certainly allowable [Cox suggested] to try the effect of certain deceptions, contrived to make strong impressions on the senses, by means of unexpected, unusual, striking, or apparently supernatural agents; such as after waking the party from sleep ... by imitated thunder or soft music ... combatting the erroneous deranged notion, either by some pointed sentence, or signs executed in phosphorus upon the wall of the bedchamber, or by some tale, assertion, or reasoning by one in the character of an angel, prophet, or devil.14

There are plenty of comparable cases recorded in classical and early-modern literature, and in the latter cases particularly the notion of the physician as performer seems to have been associated with materialist medicine seeking alternatives to narratives of supernatural possession. The doctors’ performances are undertaken as pure charade, any ‘supernatural agents’ having no actual role in any part of either the delusions or the affect that will form part of their cure.15

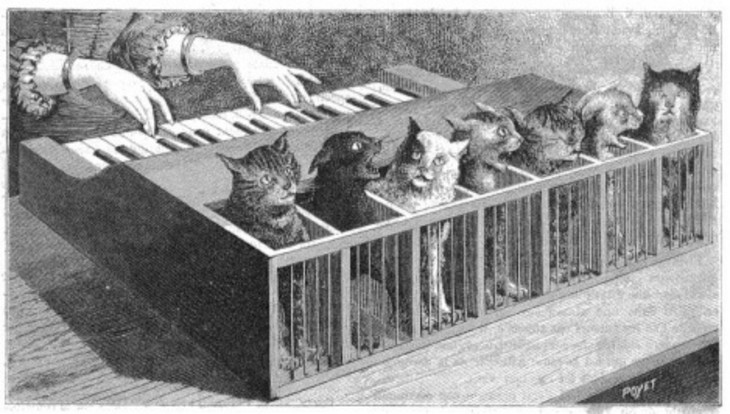

Poyet

Cat-Keyboard (Katzenklavier) Wood engraving from La Nature, 1883, p. 283

Bibliothèque du Cnum 4° KY 28.

Photo © Cnum – Conservatoire Numérique

Fig.5

Poyet

Cat-Keyboard (Katzenklavier) Wood engraving from La Nature, 1883, p. 283

Bibliothèque du Cnum 4° KY 28.

Photo © Cnum – Conservatoire Numérique

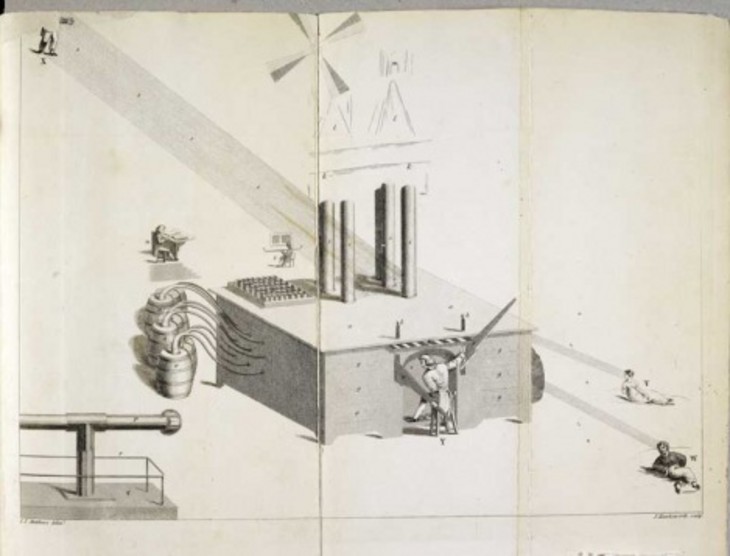

The Air Loom From Haslam, Illustrations of Madness p.181

By permission of the British Library (1191 I 7)

Fig.6

The Air Loom From Haslam, Illustrations of Madness p.181

By permission of the British Library (1191 I 7)

John Robert Cozens 1752–1797

Satan Summoning his Legions c.1776

Watercolour on paper

support: 288 x 334 mm

Tate T08231

Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996

Fig.7

John Robert Cozens

Satan Summoning his Legions c.1776

Tate T08231

Rod Dickinson

The Air Loom, A Human Influencing Machine 2002

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle

Photo © The artist

Fig.8

Rod Dickinson

The Air Loom, A Human Influencing Machine 2002

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle

Photo © The artist

Haslam’s arrogant dismissal of just about every other British opinion concerning lunacy extended also to the new experiments being made in ‘moral therapy’. Pioneered by Quakers from the 1790s, this new ideal in caring for the mentally ill embraced the tradition of engaging with the delusions of patients so disapproved of by Haslam and added to it a zero-tolerance approach to the physical punishment or restraint of patients.27 The entire project was underwritten by an Evangelical rhetoric of love and hope, but, wedded as it soon became to the state’s determination to remove the unstable from society and ‘warehouse’ them in asylums, moral therapy and the non-restraint movement wear, for Foucauldian historians, the smiling face of a malignant and coercive apparatus. Certainly, the new doctrine of loving confinement brooked no opposition, swiftly crushing those side-tracked by the new consensus.28 Bethlem, as the symbol of the psychiatric ancien régime, found itself, despite Haslam’s claims as a moderniser, in the firing line in 1814. The Quaker MP Edward Wakefield forced his way into the collapsing hospital and made the country shudder with his reports of what he saw there.29

Crucial to the impact of his evidence was the reproduction in the press of a drawing of a Bethlem patient commissioned by Wakefield from the landscape artist George Arnald.30 James Norris was an American marine and, according to Haslam, a ferociously dangerous patient, whose unusually jointed wrists meant that ordinary manacles could not restrain his violent impulses. This special harness was therefore constructed especially for him. Here, in the hands of the lunacy reformers, the structure of fear has been turned inside out. Rather than the patient being improved through terror, now the psychiatric profession will be reformed through the dismay artfully generated in the public by imagery such as this.

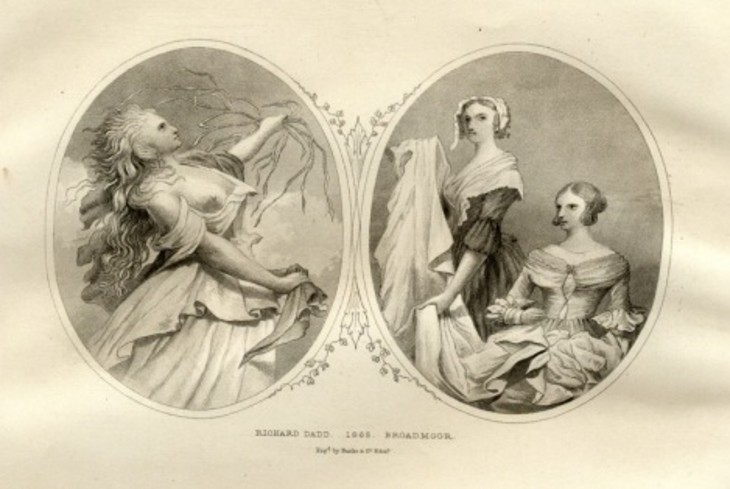

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

Engraving

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

Fig.9

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

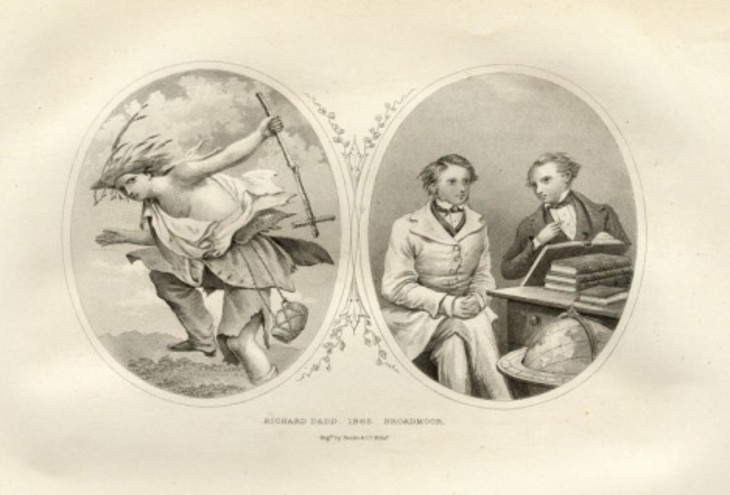

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

Engraving

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

Fig.10

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

As a coda I should like to jump forward to the 1860s and to one further image by a psychiatric patient facilitated by a doctor (fig.9). This is the certificate awarded by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh to recipients of the Morison Prize, asylum attendants who had demonstrated humane attention to their patients over long periods of service.31 The award was named after Alexander Morison who had been another Bethlem physician and a patron of Bethlem’s most famous Victorian inmate, the painter Richard Dadd. In 1864 Dadd was moved to the new State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Broadmoor from where he must have sent Morison the two pairs of designs used for the male and female versions of the certificates (fig.10). In each, an image from the Elizabethan stage forms the ‘before’, and a pair of calmly productive figures forms the ‘after’ – one of these is the patient and the other the attendant, but it is not at all clear which is which. Dadd’s designs appear to follow Victorian orthodoxy in celebrating the suppression of the lonely, sublime maniac and the patient’s entry into socialising moral therapy. But Dadd’s images seem also to prophesy the development within asylum medicine of the new genus of psychosis – the schizoid paradigm that was to inform the psychiatric profession, and the anti-psychiatry movements, of the twentieth century.32

Notes

Frederick Reynolds, The Life and Times of Frederick Reynolds, Written by Himself, 2 vols., London 1826, vol.2, pp.23–4: the anecdote has been reprinted several times, e.g. Ida Macalpine and Richard Hunter, George III and the Mad Business (1969), London 1991, pp.271–2, and Andrew Scull,The Most Solitary of Afflictions. Madness and Society in Britain, 1700–1900, New Haven and London 1993, p.69 n.89. Burke’s political interest was in supporting the proposed Regency and he was therefore not impatient to see the King cured.

For another self-congratulatory description of a mad-doctor’s use of ‘the eye’, see William Pargeter, Observations on Maniacal Disorders, Reading 1792, pp.49–52.

Michael Macdonald, Mystical Bedlam. Madness, Anxiety, and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England, Cambridge 1981, p.230: the next sentence reads, ‘The eighteenth century was a disaster for the insane.’ Macdonald’s title is borrowed from a 1615 sermon equating religious enthusiasm with madness. On the place of Lockean psychology in the history of British psychiatry, see Michael V. DePorte, Nightmares and Hobbyhorses: Swift, Sterne and Augustan Tales of Madness, San Marino, California 1974.

A mad-doctor such as Willis confidently retained a humoural component to his treatments: he apparently favoured applying blisters to the ankles to draw the humoural excess away from the brain down to the lower parts of the body (Macalpine and Hunter, George III, 1991, p.273).

Frances Ferguson, Solitude and the Sublime. Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Individuation, New York and London 1992, ch.2. Burke’s Enquiry of course opens with an introduction ‘On Taste’ defending the notion that questions of feeling might properly be formally argued over.

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757), ed. James T. Boulton, London 1958, p.136: ‘a mode of terror is the exercise of the finer parts of the system’. For other writers, however, the sublime was entirely distinct from terror: see, for example, Joseph Priestly in Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla (eds.), The Sublime: A Reader in British Eighteenth-Century Aesthetic Theory, Cambridge 1996, p.122. For a parallel discussion of the interactions between Burke’s sublime and physiological medicine, see Aris Sarafianos, ‘The Contractility of Burke’s Sublime and Heterodoxies in Medicine and Art’, Journal of the History of Ideas, vol.69, no.1, 2008, pp.23–48.

Ibid., p.127; Philip Shaw, The Sublime, London and New York 2006, p.126 (on Lyotard). In earlier periods the delusional certainties of the insane were regularly compared to the supposedly fanatical religious beliefs of non-Western cultures, especially Hinduism and Islam.

Scull, The Most Solitary of Afflictions, p.73. Various sorts of dramatic water-treatments were suggested and implemented, and in Romantic Germany there seems to have been a quasi-baptismal enthusiasm for them, for example, at La Charité at Berlin where early in the nineteenth century Ernst Horn drenched his patients in epic quantities of water (he was also keen on rotatory machines). Among the classical writers advocating shock therapies was the second-century AD Alexandrian anti-Christian polemicist, Celsus.

Macalpine and Hunter, George III, p.78 (January 1789); during the King’s later illness, in 1811, Rush’s chair was considered for use but not adopted (ibid., p.279).

Cox describes, or imagines, cases ‘where a frog, snake, or toad, &c. is believed to inhabit the stomach, and the maniac refuses to take nourishment’: here, he says, vomiting should be induced, and a live specimen of the appropriate animal hidden in and then produced from the bucket. Compare the earlier similar deception in Macdonald, Mystical Bedlam, pp.153–4 (see also another charade at p.196); and for the famous case of Pinel in Paris pretending to try and acquit a man convinced he would become a victim of the Terror, see Mike Jay, The Air Loom Gang, London 2003, pp.243–4.

This is the translation of the title given by Robert J. Richards, ‘Rhapsodies on a Cat-Piano, or Johann Christian Reil and the Foundations of Romantic Psychiatry’, Critical Inquiry, vol.24, no.3, 1998, pp.700–36, p.702: I know of no full English translation of the book.

Reil imagines a resolution of all madness as part of general human progress led by the romantic philosophers: ‘Over all of this, a sublime group of speculative Naturphilosophen soars like an eagle. They assimilate their earthly booty into the purest ether and return it again as beautiful poetry’ (Reil 1803, p.53, trans. and quoted Richards, ‘Rhapsodies on a Cat-Piano’, p.723).

Scull, The Most Solitary of Afflictions, p.73, n.106. Richards doubts the Katzenklavier was ever constructed, although there are various literary references to it. Richards, ‘Rhapsodies on a Cat-Piano’, p.721, n.50.

The explosion of British literature on lunacy is sometimes seen to have been initiated by the appearance, a few months after Burke’s Enquiry, of William Battie’s Treatise on Madness. Battie sought to expand the discourse around the alienist’s profession and to remove its practice in London from the exclusive hold of the Monros of Bethlem. Battie’s painstakingly precise book, however, concludes with little more than a plea to minimise depleting treatments and an acceptance that a patient’s passions must be managed contrapuntally in the manner of humours so as to produce, for example, ‘fear substituted in the room of anger, or ... sorrow immediately succeeding to joy’ (William Battie, A Treatise on Madness by William Battie, M.D., and Remarks on Dr. Battie’s Treatise on Madness, by John Monro, M.D. A Psychiatric Controversy of the Eighteenth Century, introduced and annotated by Richard Hunter and Ida Macalpine, London 1962, p.84.)

See John Haslam, Illustrations of Madness (1810), ed. Roy Porter, London 1988, and Jay, The Air Loom Gang, 2003.

On the ‘Monro school’, see Andrew Wilton, ‘The Monro School Question: Some Answers’, Turner Studies, vol.4, no.2, Winter 1984, pp.8–23.

The plate in Haslam, Illustrations, 1810/1988 was ‘sketched by Mr. Matthews’ (p.42) and engraved by J. Hawksworth.

See Thomas Röske and Bettina Brand-Claussen (eds.), The Air Loom and Other Dangerous Influencing Machines, Heidelberg 2006, pp.69 ff.

On the Quaker tradition of non-restraint in the treatment on lunatics, going all the way back to George Fox, see Macdonald, Mystical Bedlam, pp.228–30. On the innovations of the 1790s, see Anne Digby, Madness, Morality and Medicine: A Study of the York Retreat, 1796–1914, Cambridge 1985.

There were comparable initiatives all over Europe at this period: see Erwin H. Ackerknecht, A Short History of Psychiatry [1959] rev. ed., trans. Sula Wolff, New York and London 1968, pp.34–5. In Britain, the defining moment signalling the beginning of the non-restraint movement was always taken to have occurred in Paris when Pinel removed the chains from the lunatics of the city’s asylums during the Revolution – a myth of very ambiguous political implications. Once ‘non-restraint’ had achieved full hegemony by around mid-century, the supposed earlier excesses of romantic psychiatry were held up to ridicule, and in the self-consciously outraged hands of a campaigner such as John Conolly, the recycled stories of ‘sublime’ treatments generate yet another layer of literary elaboration around the subject (John Conolly, The Treatment of the Insane before and after the Advent of Moral Management, London 1856, pp.12–16).

See Andrews et al., The History of Bethlem, ch.23; the Parliamentary enquiry that followed led to both Thomas Monro and Haslam losing their jobs.

Arnald made a first sketch at Bethlem in May 1814 which he published himself as an etching surrounded by an account of the case (Scull, The Most Solitary of Afflictions, p.94; Andrews et al., The History of Bethlem, pl. 23.1); subsequently a second drawing made by Arnald in June 1814 was etched by George Cruikshank for the Radical publisher William Hone (published July 1815 and illustrated here). That the reformers did not trouble to get Norris’s name right (they call him William) seems revealing: what counted was the image.

See Joy Pitman, ‘Papers of the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Insane’, Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, vol.24, 1994, pp. 420–7.

Within clinical psychiatry today the sublime may have as little meaning as ‘awesome’ in the American sense: see H. Steven Moffic, ‘In Search of Sublime Psychiatry’, Clinical Psychiatry News, vol.36, no.5, May 2008, p.66. Clarkson and her contributors, meanwhile, use the sublime as a peg on which to hang a woolly tapestry of Jungian typologies. Petruska Clarkson, On the Sublime in Psychoanalysis, Archetypal Psychology and Psychotherapy,London 1997.

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was first presented at the conference The Sublime in Crisis: New Perspectives on the Sublime in British Visual Culture 1760–1900 held at Tate Britain in September 2009, organised by the AHRC-funded research project ‘The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language’.

A version of this paper was first presented at the conference The Sublime in Crisis: New Perspectives on the Sublime in British Visual Culture 1760–1900 held at Tate Britain in September 2009, organised by the AHRC-funded research project ‘The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language’.

Nicholas Tromans teaches at Kingston University.

How to cite

Nicholas Tromans, ‘The Psychiatric Sublime’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www