Sex and the City: The Metropolitan New Woman

Meaghan Clarke

Several Camden Town paintings show women confidently walking through the city or using public transport. Meaghan Clarke explores the opportunities for increased independence for women at this time, showing how the 1890s concept of the New Woman continued to play a role in framing gender relations in the Edwardian era.

Charles Ginner’s Piccadilly Circus of 1912 (Tate T03096, fig.1) represents a busy metropolitan space with bright red paint marking out motor buses passing by the island with the statue of Eros. Piccadilly Circus had been the site of new building construction and realigned as part of a massive road-building scheme initiated in the 1880s along with the reconstruction of the Thames Embankment, Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue.1 In Ginner’s picture, a green motor taxi appears in the foreground adjacent to the profile of a flower seller. Amidst the hubbub of London and its multiple modes of transport, a young woman dressed in black marches confidently by. A year later Ginner turned to another busy urban scene in The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station (fig.2). A major London terminus, Victoria Station was greatly enlarged between 1902 and 1908. In 1901 the station yard had been described as ‘crowded with omnibuses, hansoms, four-wheelers, private carriages, vans and carts, as if to convince [foreign visitors] of the energy and confusion of London life’.2 In a series of works around 1912, Ginner presented fascinating images of modernity, new architecture and engineering in a vibrant, bustling metropole. Moreover, his paintings offer an intriguing depiction of the modern woman striding purposefully through the city. Indeed, the Camden Town Group artists, although lacking female members, frequently depicted women traversing the city’s streets and squares, waiting at train stations and meeting at cafés. This essay considers the character and evolution of this Edwardian modern woman in relation to the phenomenon of the New Woman of the fin de siècle as represented in contemporary popular culture and fine art.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.1

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Oil paint on canvas

43 x 51 cm

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

By the early 1900s women were becoming increasingly visible in metropolitan London. In politics, calls for democratic enfranchisement were raised at public meetings by ‘platform women’ and suffrage associations. Professionally, women entered the workplace in ever greater numbers; periodicals regularly noted their successes in the fields of medicine, education and journalism to name a few. Moreover, women were active participants in the developing pleasure and leisure economy of the modern city. Their day to day perambulations meant that they too might be regarded as city voyeurs or ‘flâneurs’,3 moving about the city via new modes of transport – bicycle, bus, Underground and automobile – and experiencing the greater mobility the city could offer.

Much writing about the New Woman has focused on her literary representation.4 The phrase itself first appeared in the writings of the feminist Sarah Grand and the popular novelist Ouida in 1894 and was rapidly taken up by the press, quickly coming to be associated with young women pursuing personal freedom and individualism, and symbolised by the latchkey, the bicycle, the cigarette and modern dress.5 While initially mocked on the pages of Punch, these figures were nevertheless widely depicted in public spaces as well as in portraiture. Although the peak of the New Woman phenomenon is generally equated with novels of the mid-1890s, her political, social and cultural impact continued well into the Edwardian period and beyond. The New Woman was not, however, a unified category and the contradictory nature of the visual representations of women across the period 1894–1914 are indicative of wider contemporary tensions relating to gender and labour.

The modern woman and the New Woman

Stanislawa de Karlowska in her artist's smock c.1897–8

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.3

Stanislawa de Karlowska in her artist's smock c.1897–8

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

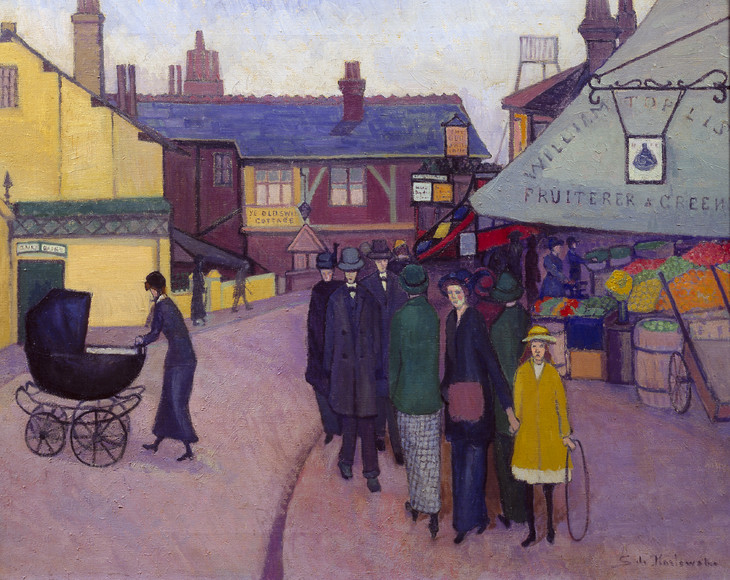

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 337 x 394 mm; frame: 440 x 496 x 72 mm

Tate N06238

Presented by the artist's family 1954

© Tate

Fig.4

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Tate N06238

© Tate

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Berkeley Square c.1935

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 510 mm

Tate N04816

Presented anonymously 1935

© Tate

Fig.5

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Berkeley Square c.1935

Tate N04816

© Tate

Challenges to women’s conventional roles were more forcefully articulated in the first decade of the new century as the political agenda of the modern woman moved to the forefront of popular culture. The Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) were frustrated by the slow tactics of Victorian pressure groups and, as a result, helped to establish a militant campaign. By the 1906 election the women’s cause had become a topical issue; however, the indifference of the resultant Liberal government urged the campaign on to greater visibility. As art historian Lisa Tickner has demonstrated in a 1987 chapter on the subject, it was not only militancy that distinguished the Edwardian suffrage movement, but a new politics of spectacle and political propaganda.7 From 1907 more Edwardian women were politicised through the public suffrage demonstrations. The Artists’ Suffrage League was formed ‘to promote the cause of women’s enfranchisement by the work and professional help of artists’.8 Up to 40,000 women at a time took part in a series of elaborately orchestrated demonstrations between 1907 and the suspension of suffrage activity with the beginning of the war in 1914. All of these activities occur in the period of the Fitzroy Street, Camden Town and London Group formations.

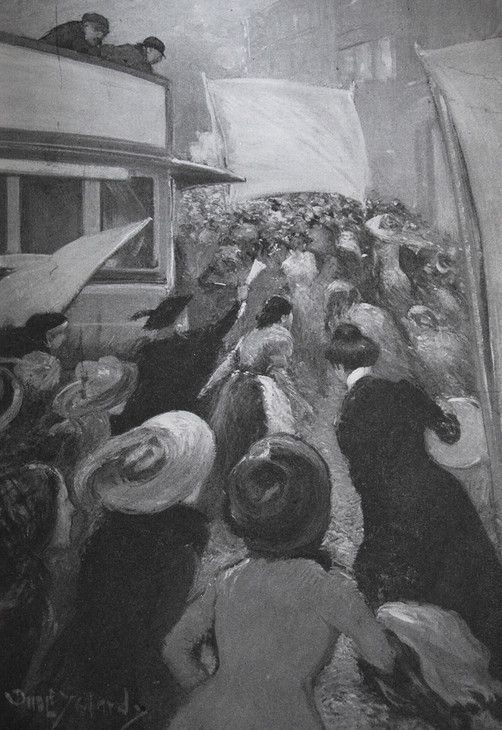

As women increasingly participated in activities ranging from electoral reform to motor car driving, Punch continued to publish mocking representations. Other journals, however, took up the challenge of their defence. In 1911 the editor of the Lady’s Realm handed over the January issue, entitled ‘Quo Vadis’ (Where are you going?), to ‘three women publicists, from England, Germany, and France’ to write on the topic of the ‘general unrest among women’.9 The issue’s cover features a street thronging with women holding aloft banners reading ‘Quo Vadis?’ and ‘We Demand Change’, as well as a barely visible ‘V’ seeming to indicate ‘Votes’. In various forms of dress, ranging from an academic gown and hat to an apron, the women march past two men peering over an advertisement that asks, ironically, ‘Why not spend day at Selfridge’s’. There had been several processions during the parliamentary campaigns of the previous year, including the spectacular joint NUWSS and WSPU demonstration of 40,000 women in June. The Conciliation Bill had had two readings in July, but the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith refused facilities to further the Bill and it was subsequently shelved. This was followed a month before the second election by the ‘Black Friday’ WSPU demonstration on 18 November in Parliament Square when women were violently and sexually attacked by police.10

Whither goest thou? January 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Fig.6

Whither goest thou? January 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Dudley Hardy c.1867–1922

Are the lights in the New Year's sky of 1911 a false dawn, or do they presage the coming of a new and better day? January 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Fig.7

Dudley Hardy

Are the lights in the New Year's sky of 1911 a false dawn, or do they presage the coming of a new and better day? January 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

The Lady’s Realm illustration reappeared inside the journal with the title ‘Whither goest thou?’ (fig.6), along with a frontispiece image of a blindfolded allegorical female figure turning toward a rising sun with the query, ‘Are the lights in the New Year’s sky of 1911 a false dawn, or do they presage the coming of a new and better day?’ (fig.7). Two more illustrations of fashionable modern women mid-speech presumably referenced the primacy of the platform.11 In the accompanying article the correspondent declared:

Those who cry that woman was better off under the old régime are speaking idly to the wind.

The old régime is over.12

The old régime is over.12

Lady's Realm frontispiece April 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Fig.8

Lady's Realm frontispiece April 1911

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

In addition to dress, another shift for modern women was in attitudes to sexuality. The issue of sexual independence had been a feature of writing on the New Woman and in egalitarian feminist politics. Figures such as birth control campaigner Annie Besant crucially advocated new choices for women.16 It was these aspects of New Womanhood that were taken up by several modern bohemian women. Debates were explicitly articulated on the pages of three radical journals, beginning in November 1911 with the Freewoman edited by Dora Marsden and Mary Gawthorpe and followed by the New Freewoman and the Egoist. Both Marsden and Gawthorpe had been active members of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union, but left owing to conflicts with leadership. The Freewoman proclaimed in its opening editorial, ‘woman is an individual and she must be set free’, as opposed to a ‘bondwoman’ who was not a separate entity.17 The journal gave space to frank discussions on sex and marriage. These ‘new moralists’ rejected the ‘womanly woman’ and the ‘old morality’ of marriage, denouncing it as the condition of the ‘bond-woman’, legalised breeding and prostitution. Much debate was provoked on the subject of sex and ‘free love’ and letters to the editor tackled subjects such as ‘Pruriency and Sex discussions’ and ‘Uranians’ (a term associated with a group of late nineteenth-century homosexual poets). ‘A New Subscriber’ offered an extended analysis of recent correspondence on the topic of women, proclaiming:

There is probably a far greater range of variation sexually among women than among men, and the sister or friend of a cold-blooded woman may be capable of intense sexual emotion.18

The writer went on to reference the theorist of sexology Havelock Ellis, determining that very few women engaged in total ‘sexual abstinence’. While Ellis, with his exaggerated emphasis on motherhood, might be seen to have had negative implications for feminists, one viewpoint that emerged with particular resonance for the Freewoman was that women were sexual beings.19 It was this new perspective that was emancipatory not only for women readers of the journal, but also female members of London’s bohemian set.

The origins of Edwardian female radicalism can be clearly traced back to the 1890s, with the cultural, political and spatial shifts increasingly evident in women’s lives. Indeed, the changing structure of British society was in good part a result of the collective identities and struggles of women that had emerged on a national scale in that decade.20 As Lynne Walker has demonstrated, by the late nineteenth century the intersection of gender, space and new experience offered opportunities for independent middle class women to develop new identities.21 Despite this, some writers, such as Talia Schaffer, have questioned whether New Women were largely the creation of the publicity of the period.22 The press was certainly an important facet, being instrumental both in women’s visual representation, and in itself a viable career option for women. The creation of the Society of Women Journalists in 1894 coincided with the emergence of the New Woman, and female journalists became increasingly visible both in print and in the city. Consequently, changes in women’s social and sexual roles became identified with what was radically new in the press.23

In the 1890s the New Woman had frequently been portrayed in Punch in a series of stereotypes of unattractive single women. ‘Donna Quixote’, for example, gleans radical notions from the books surrounding her: ‘A world of disorderly notions picked out of books, crowded into his (her) imagination.’24 Punch ridiculed these new female figures, but at the same time drew attention to their existence; women were subsequently instrumental in moulding that visual caricature. One such was Ella Hepworth Dixon who had published The Story of a Modern Woman in 1894 and as an independent woman journalist fitted the stereotype of the New Woman, much like the protagonist in her story, Mary Erle, the daughter of a prominent academic. Like a Punch caricature, Hepworth Dixon rode a bicycle around the city and wrote for periodicals such as the Lady’s Realm. Her own memoirs, however, contradict the image of the mannish figure with pince-nez and latchkey, intent on reading rather than socialising. Instead she describes how, in the ‘untidy, happy-go-lucky Bohemia of the nineties’, her early ‘journalistic activities were mixed up with a great deal of dancing and dining out; white tulle skirts and natty little laced up bodices took the place of an evening of inky fingers’.25 Hepworth Dixon’s description of her lifestyle has more in common with a type of independent New Womanhood often conflated with decadent ‘femmes fatales’ or highly sexualised women who showed their independence by pursuing free sexual relations.26 These women disregarded scientific discourses that promoted the role of women in heterosexual reproduction; but the fear of unmarried, childless women fed into those popular stereotypes in Punch as well as in contemporary eugenics.27 Some women had earlier pursued a genuine scientific interest in sexology and ‘free love’ as members of the early socialist and later eugenicist Karl Pearson’s Men and Women’s Club (founded in 1885) and their debates were later articulated in the Freewoman, while others pursued both glamour and independence.28 The social life and career of women such as Hepworth Dixon indicate the choices available to the modern woman in the following decade.

As the social historian Penny Tinkler has underlined, cigarette smoking was to be an important symbol of social independence among those who were identified as New Women or supported the suffrage movement.29 Smoke curls up the border of the poster advertising Sydney Grundy’s 1894 play, The New Woman.30 Cartoons and articles in Punch inevitably mocked the smoking New Woman, and in one series of ‘Letters to the Editor’ smoking and transport are conflated as signifiers of female defiance:

I notice in the columns of a popular newspaper a discussion under the heading ‘The Ladies’ Invasion’ in which it is asked whether women have any right to invade the men’s smoking compartments. This suggests a wider question. Why should women want to travel by train at all?31

In a Punch cartoon two women dressed in shirts and ties lounge on chairs in front of a table of books, chatting over cigarettes while a man makes for the door, off for a ‘cup of tea in the servant’s hall. I can’t get on without Female Society, you know!’32 Here Punch represents anxieties about the breakdown of traditional social hierarchies; the women have assumed masculine roles and the man is feminised by contrast. Not all descriptions of women smoking were negative, however; the art critic Gertrude Campbell remarked in 1893 that tobacco was particularly suitable for women as they coped with the demands of ‘multitudinous modern developments and exigencies’.33

Miss Marie Tempest August 1912

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Fig.9

Miss Marie Tempest August 1912

Courtesy of St Peter's House Library, University of Brighton

Photo © Tate

Stanislawa de Karlowska smoking in the doorway of Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.10

Stanislawa de Karlowska smoking in the doorway of Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Although prevalent in the popular press, smoking women were most frequently depicted as prostitutes or radicals, until the Edwardian period. The Lady’s Realm of 1908 includes an image of a fashionably dressed young woman with the heading, ‘Don’t be shocked, Aunt Cathie, but I occasionally smoke’.34 In 1912 a glamorous photograph of the actress and singer Marie Tempest was featured on the frontispiece, smoke curling upwards from the cigarette held in her right hand (fig.9).35 A photograph of Stanislawa de Karlowska from c.1917–18 likewise signals her modernity; she stands in the doorway of the cottage she shared with Robert Bevan near Clayhidon in Devon dressed in a skirt and blouse and a long light smock tied at the waist smoking a cigarette (fig.10). Unlike Tempest, Karlowska’s portrait was not a publicity shot; she is an artist just turned away from her work for a cigarette. By the early 1910s smoking was common across London’s bohemian culture and for its female members it indicated independence and participation in artistic circles.

Related to this developing independence, late Victorian and Edwardian women’s clubs, like those of men, offered social comfort and professional networking. Founding members of the Literary Ladies Club, begun in 1889, were later identified as New Women. The club claimed equal status and privileges as those enjoyed by male authors and was part of the larger entrance of women into the public spaces of London. Likewise, Constance Smedley’s Lyceum Club, which opened in 1904 into a citadel of masculinity in Piccadilly, the men-only Imperial Service Club, literally invaded male space and metaphorically the masculine public sphere. For the cultural historian Erika Rappaport, these women’s clubs developed out of a feminist critique of a male-oriented city; they combined shopping with other activities such as debating the suffrage or tariff reforms. Some helped create a community of women, while others helped to legitimise heterosocial amusement. They all confirmed a place for women in the urban centre.36

Despite all of these developments from the 1890s, however, the Camden Town Group, by contrast, remained a male-only preserve.37 Associated female artists and writers were forced to find alternative spaces and networks at home or in the city. Karlowska, for example, exhibited with the Women’s International Art Club, originally the Paris Art Club, which facilitated international cooperation among established artists and countered those institutional and critical strategies that were displacing women from definitions of modernity in art.38

The Café Royal in Regent Street was particularly associated with an artistic clientele; its interior was painted by Charles Ginner (Tate N05050, fig.11), Harold Gilman, Adrian Allinson, Sidney Starr and William Orpen. Weekly Saturday gatherings took place there of Lucien Pissarro, Walter Sickert, Augustus John, Spencer Gore, Gilman, Bevan and also Karlowska. According to the playwright, Ashley Dukes, the Camden Town Group models often attended too, so there was no lack of women.39 While at one time women were not allowed to enter the café unaccompanied, the wife of C.R.W. Nevinson famously walked in alone and blithely ordered a meal for herself.40 The rule was eventually relaxed. In addition to Karlowska, other women artists and writers frequented the café in the pre-war period, including the writers Katherine Mansfield and Nancy Cunard and the artist Nina Hamnett.41

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.11

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

Adrian Allinson 1890–1959

The Café Royal 1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

102 x 127 cm

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

Fig.12

Adrian Allinson

The Café Royal 1915–16

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

Cunard and Iris Tree’s entrance into the café was legendary in contemporaries’ accounts;42 they wore their hair short, with theatrical make-up, and one was dressed in pantaloons narrowing at the ankle, the other in a patched skirt. Both were financially independent, able to adopt a rebellious bohemian lifestyle while still in their teens; they soon became habitués of the café. The pair is depicted in Adrian Allinson’s painting of 1915–16 (fig.12): Cunard is seated in the foreground opposite Alan Odle, her cropped fair hair in bold contrast to her dark suit; behind her on the left is seated Tree with Horace de Vere Cole and Evan Morgan, while Dorelia John is to the right of centre conversing with Augustus John; the fourth woman on the far right is supposedly Allinson’s mistress, the ceramicist Molly Mitchell Smith.

Hamnett similarly wore provocative outfits and was stared at on Tottenham Court Road: ‘I wore white stockings and men’s dancing pumps ... One had to do something to celebrate one’s freedom and escape from home.’43 Having already witnessed the Ballets Russes in Russia in 1909, she rapidly became the centre of bohemian coteries in London and Paris,44 drinking crème-de-menthe frappées at the Café Royal, moving onto the late-night cabaret club, the Cave of the Golden Calf, frequented and decorated by members of the Camden Town Group, and attending Sickert’s ‘At Homes’ at 19 Fitzroy Street. She was indeed the subject of one of Sickert’s paintings in 1915–16 (Tate N05288), seated on a chaise longue smoking a cigarette beside her husband (for three years), Roald Kristian. In addition to wearing her hair short, she also frequently wore trousers. Bohemian women like Hamnett, Tree and Cunard were engaged in a life of masquerade where their leading art exhibit was their own public image.45 It was fundamentally their radical dress and a stridently independent lifestyle that was unique to those modern women who frequented the Café Royal in the early 1910s.

Portraying New to Modern Woman: modernity and fashionability

For Erica Rappaport, by the end of the nineteenth century:

middle-class women played two roles in the glamorous metropolis. They acted the part of the voyeur who travelled in, gazed at, and wrote about the urban spectacle. They were also among the desirable objects on display in this marketplace.46

The advent of the New Woman had coincided with the zenith of society portraiture and the world of fine art embodied the glamorous metropolis for women; yet portraits also reflected an ambiguity, revealing anxieties around the specificity of male and female roles and relationships.47 Moreover, the independent identities of women members of artistic and literary circles subverted their role as ‘desirable objects’.

![Sir William Rothenstein 'Mrs Meynell [Part IX]' 1897](https://media.tate.org.uk/art/images/research/57_9.jpg)

Sir William Rothenstein 1872–1945

Mrs Meynell [Part IX] 1897

Lithograph on paper

image: 136 x 152 mm

Tate P11041

Presented by Sir John Rothenstein through the Friends of the Tate 1981

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.13

Sir William Rothenstein

Mrs Meynell [Part IX] 1897

Tate P11041

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Sargent’s 1897 portrait of Edith Newton Phelps Stokes epitomises the New Woman of that era, another striking antecedent for the Edwardian modern woman. She stands hand on hip, in a shirt-waist, tie, skirt and jacket. With her frontal pose, direct gaze and with a straw hat balanced on her hip, she exudes confidence and vivacity (fig.14). In her memoir Stokes reported that it was Sargent who changed his initial plan of painting her in a formal evening dress, deciding instead to paint her looking just as she had arrived one morning, full of energy from a brisk walk. Her husband, a later addition, recedes into the background emasculated by the positioning of her hat.54 However, Stokes was a wealthy American, not a woman of modest means pursuing an artistic career in London or Paris. It was the latter that went on to offer challenging representations of New Womanhood in the Edwardian period.

John Singer Sargent 1856–1925

Mr and Mrs I.N. Phelps Stokes 1897

Oil paint on canvas

2140 x 1010 mm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Edith Minturn Phelps

Photo © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

Fig.14

John Singer Sargent

Mr and Mrs I.N. Phelps Stokes 1897

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Edith Minturn Phelps

Photo © 2011. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

Gwen John 1876–1939

Self-Portrait 1902

Oil on canvas

support: 448 x 349 mm

Tate N05366

Purchased 1942

Fig.15

Gwen John

Self-Portrait 1902

Tate N05366

Gwen John is a key example. One of several women who studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in the 1890s, later moving to Paris to study at Whistler’s Académie Carmen, John’s independent lifestyle and the character of her self-portraits identify her with the New Woman of the period. A striking self-confidence is evident in her Self-Portrait of c.1900 (National Portrait Gallery, London),55 which makes use of conventions of society portraiture while also presenting an alternative femininity. In her 1999 study of the artist, Alicia Foster sees John’s 1902 self-portrait as an image of a self-contained woman of psychological depth (Tate N05366, fig.15).56

Artists of John’s generation increasingly favoured smaller portraits on a domestic scale. John follows this trend in this work, using a half-length composition more akin to male artists’ self-portraits. Her self-presentation in a working blouse and bold tie also distinguishes her from the spectacular portraits of wealthy female sitters portrayed in luxurious fabrics.57 She was followed at the Slade by a generation of modern women, some of whom also cut their hair short, such as the ‘crop-heads’ Iris Tree and Dora Carrington.

Both male and female artists associated with the Slade and later the Camden Town Group were concerned with diverse representations of the modern woman rather than large spectacular portraits of society beauties. They attended to the multiplicity of types across class and social status in the metropole, ranging from working class women, flower sellers and coster women to portraits of the artists themselves and their families. The market for these smaller portraits was also distinctly different from that of the portraits of the wealthiest members of London society. The works were targeted at middle class buyers with financial means more similar to those of the artists themselves.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Artist's Wife 1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 765 x 636 mm; frame: 918 x 790 x 80 mm

Tate T03561

Presented by Frederick Gore, the artist's son 1983

Fig.16

Spencer Gore

The Artist's Wife 1913

Tate T03561

Several female members of avant-garde circles were experimenting with dress by this period. In newspaper photographs from the vorticist Rebel Art Centre, Kate Lechmere, for example, appears in a gown in the fashionable tubular shape popularised both by Poiret and the Ballets Russes.58 The art historians Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry observe that the gown could have been purchased in Paris or, like many women artists, Lechmere may have designed or made it herself.59 Kerr’s apparel clearly registered her as a woman of advanced artistic taste. Her hair is also bobbed, a daring cut more widely popularised by the American dancer Irene Castle around 1914. The artist and model Nina Hamnett similarly had her hair cut in a bob by the sculptor Ossip Zadkine so that she resembled one of his statues.60

Urban mobility

The transformation of modern women as circulated visually through portraiture signals the dramatic changes to their physical presence in the city. Not only were there radical sartorial alternatives for women, their movement through the metropolis was facilitated by the growth in public transport, as exemplified by the omnibus in Ginner’s Piccadilly Circus (Tate T03096, fig.1). For women, the possibility of urban mobility had emerged in the previous decade and became a crucial feature in their developing independence. The expansion of cheap public transport had transformed the experience of late Victorian Londoners. During the 1890s the railways had allowed suburbs to grow out from the city, which were connected between the radii by horse-drawn buses and trams. It has been estimated that by 1900 these trains carried 500 million passengers a year in Greater London. The growth of electric tramways, buses and the Underground offered further travel options that rapidly expanded after the turn of the century.61 Atlases and other guidebooks encouraged visitors to use some form of transport because the city was not negotiable for the pedestrian. The Lady Guide Association, as early as 1888, for example, had hired unemployed women as tour guides, chaperones, travel agents and professional shoppers.62

The painter Sidney Starr had addressed this modern theme of mobility at an early stage.63 He joined a group of artists including Mortimer Menpes who developed the habit of travelling around London on the top of an omnibus in order to record the bustling metropolitan life, a practice later highlighted by the character of Clarissa Dalloway in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) and Miriam Henderson in Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage (1915–67).64 Walter Sickert and other artists had similarly worked from the driver’s seat on top of a hansom cab during the 1880s and 1890s.65 Starr’s City Atlas 1889 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa)66 shows the back view of a young woman on the upper deck of an omnibus running through St John’s Wood in London. This followed Sickert’s dictum in the 1889 preface to the London Impressionists exhibition that the group had chosen their subjects from within a four-mile radius of London:

for those who live in the most wonderful and complex city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them.67

The art historian Anna Gruetzner Robins has suggested that the young woman in Starr’s painting is in fact a servant girl, since she occupies one of the cheaper seats on the top deck.68 However, by the late 1880s and early 1890s many women were travelling via omnibus. And, indeed, Lady magazine published a series in 1891 entitled ‘London Locomotion’ that proclaimed that not only was it now respectable for women to travel around London, viewing its sites from the top of a bus, ‘but by 1891 the “fair sex” had forced the “sterner sex” ... to take refuge inside!’69 Female custom ensured that the buses and trains remained full after the early morning commute. Consequently, transport companies targeted the market for female passengers, ensuring that middle class women and children were comfortable on the vehicles. Magazines and periodicals provided women with updates on transport routes and services. These articles assumed that ladies were travelling alone and that they required easy and comfortable routes across the city. The view from the top of an omnibus offered a particular vision from above and across, gazing almost unseen into the upper floors of private residences or down onto pedestrians. Artists and writers were intent on describing this alternative perspective on London life, and women such as Meynell and later Woolf and Richardson described women’s engagement with this new mobile ocular economy.

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Swiss Cottage exhibited 1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 762 mm; frame: 788 x 940 x 90 mm

Tate N06239

Presented by the artist's family 1954

© Tate

Fig.17

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Swiss Cottage exhibited 1914

Tate N06239

© Tate

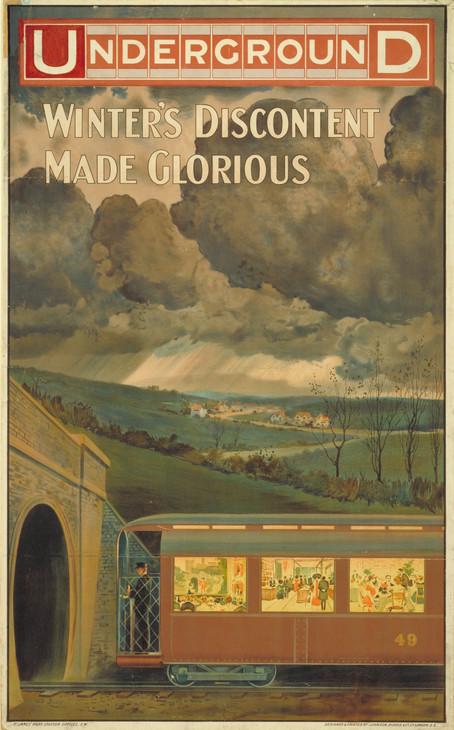

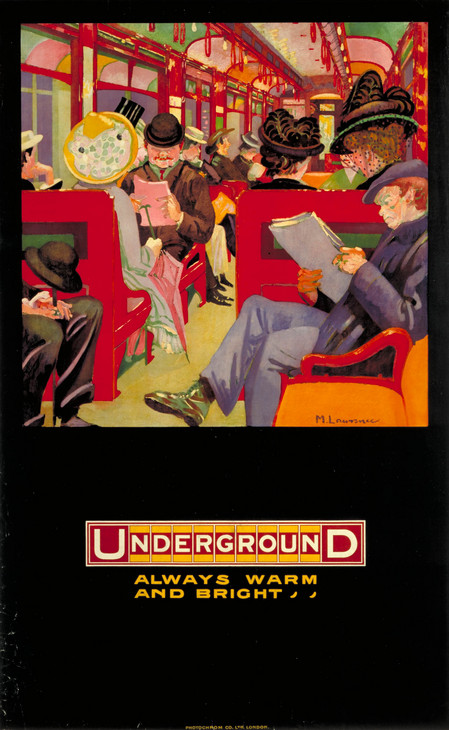

London Underground posters from 1908 frequently stressed the importance of travel for women. In the 1909 poster Winter’s Discontent Made Glorious (fig.18), women appear in three paintings on the side of a train just entering a tunnel: attending the theatre, shopping and dining in a restaurant. The red and green colours of the interior of an Underground car in Always Warm and Bright 1912 (fig.19) echo the brilliant colours of both Karlowska’s and Ginner’s representations of London. Women and men sit reading or chatting on their way into the city. Illustrations of busy London scenes thronging with people and buses also appear in a series of humorous posters by Tony Sarg where the city streets and leisure venues are teeming with people in pursuit of pleasure at the theatre, shopping or at the Royal Academy.71 Although the publicity images for the London Underground reflect the pleasures offered by the metropolis, the women in Swiss Cottage engage in work-related activities, caring for children and shopping for food. Similarly, Ginner’s Victoria Station and Piccadilly Circus indicate a wider spectrum of modern women’s use of public transport in the city, for work as well as play.

Winter's Discontent Made Glorious 1909

Poster

1004 x 622 mm

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Fig.18

Winter's Discontent Made Glorious 1909

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Mark Laurence

Always Warm and Bright 1912

Poster

1016 x 635 mm

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Fig.19

Mark Laurence

Always Warm and Bright 1912

London Transport Museum

Photo © TfL from the collection of London Transport Museum

Conclusion

As we have seen, the New Woman was not limited to the satirical image repeated across the pages of Punch in the 1890s. She exceeded the caricature of a woman with a latchkey who rode bicycles and smoked cigarettes. Smoking clearly was an important marker of autonomy and women lived independent lifestyles while travelling about the city’s public spaces. However, the vast array of images of women in the press, in portraits, cafés and urban spaces, points to the heterogeneity of possible interpretations of modern women after the turn of the century. Those associated with the new bohemian circles that overlapped with those of the Camden Town Group, in particular, presented a range of individual expressions of modernity that variously encompassed self-fashioning, artistic production and sexual emancipation.72 The origins of the modern woman in Piccadilly Circus existed in the public spaces of the metropole. In lifting the figure from her literary context, images of the New Woman result in a progressive diversity in the Edwardian era.

Notes

See Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry, ‘Reconceptualizing Vorticism: Women, Modernity, Modernism’, in Paul Edwards (ed.), Blast: Vorticism 1914–1918, Ashgate, Aldershot 2000, pp.59–72.

Arthur Henry Beaven, Imperial London, J.M. Dent, London 1901, p.294; quoted in Alastair Service, London, 1900, Crosby Lockwood Staples, St Albans 1979, p.79.

As described by Deborah Longworth, ‘The Urban Observer’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/deborah-longworth-the-urban-observer-r1105660 , accessed 21 August 2013.

See, for example, Sally Ledger, The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle, Manchester University Press, Manchester 1997; Ann Heilmann, New Woman Fiction: Women Writing First-Wave Feminism, Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000; and Carolyn Christensen Nelson (ed.), A New Woman Reader: Fiction, Articles, and Drama of the 1890s, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario 2001.

Sarah Grand, ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question’, North American Review, vol.158, no.448, March 1894, pp.270–6, http://dlxs.library.cornell.edu/n/nora/ , accessed 1 July 2010.

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, Unicorn Press, London 2008, pp.59, 134–5.

Lisa Tickner, ‘Suffrage Campaigns: The Political Imagery of the British Women’s Suffrage Movement’, in Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry (eds.), The Edwardian Era, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1987, pp.100–16.

The Editor [Mr. Vere Smith], ‘Quo Vadis? The Question of the Day’, Lady’s Realm, vol.29, no.171, January 1911, p.255, http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/pdf/december1910/Ladys.pdf , accessed 1 July 2010.

Tickner 1987, p.109; June Purvis, ‘“Deeds, not words”: Daily Life in the Women’s Social and Political Union [WSPU] in Edwardian Britain’, in June Purvis and Sandra Stanley Holton (eds.), Votes for Women, Routledge, London 2000, p.139.

Lady’s Realm, vol.29, no.171, January 1911, pp.260–1, http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/pdf/december1910/Ladys.pdf , accessed 1 July 2010.

M. Storrs Turner, ‘Quo Vadis?’, Lady’s Realm, vol.29, no.171, January 1911, p.259, http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/pdf/december1910/Ladys.pdf , accessed 1 July 2010.

Furthermore, the politicisation of vice and prostitution by social purity campaigners such as Sarah Orminston Chant enabled women to achieve a strong public profile in the debate. See Lucy Bland, Banishing the Beast: English Feminism and Sexual Morality, Penguin, London 1995.

Lynne Walker, ‘Home and Away: The Feminist Remapping of Public and Private Space in Victorian London’, in Rosa Ainley (ed.), New Frontiers of Space, Bodies and Gender, Routledge, London 1998, p.66. See also Lynne Walker, ‘Vistas of Pleasure: Women Consumers of Urban Space in the West End of London 1850–1900’, in Clarissa Campbell Orr (ed.), Women in the Victorian Art World, Manchester University Press, Manchester 1995, pp.70–85.

Talia Schaffer, ‘“Nothing But Foolscap and Ink”: Inventing the New Woman’, in Angelique Richardson and Chris Willis (eds.), The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact, Palgrave, London 2001, pp.39–52.

Margaret Stetz, ‘The New Woman and the British Periodical Press of the 1890s’, Journal of Victorian Culture, vol.6, no.2, 2001, p.273. See also Margaret Beetham, ‘Periodicals and the New Media: Women and Imagined Communities’, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol.29, no.3, May–June 2006, pp.231–40.

Reproduced in Meaghan Clarke, Critical Voices: Women and Art Criticism in Britain 1880–1905, Ashgate, Aldershot 2005, p.117.

Ella Hepworth Dixon, ‘As I Knew Them.’ Sketches of People I Have Met on the Way, Hutchinson & Co., London 1930, p.31.

Angelique Richardson, Love and Eugenics in the Late Nineteenth Century: Rational Reproduction and the New Woman, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003.

Penny Tinkler, Smoke Signals: Women, Smoking and Visual Culture in Britain, Berg, Oxford and New York 2006, p.31.

Reproduced in John MacKenzie (ed.), The Victorian Vision: Inventing New Britain, exhibition catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2001, p.106.

Reproduced in Beckett and Cherry (eds.) 1987,p.99. See also Dolores Mitchell, ‘The “New Woman” as Prometheus: Women Artists Depict Women Smoking’, Woman’s Art Journal, vol.12, no.1, Spring–Summer 1991, pp.3–9.

Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 2000, p.100.

For more on this, see Nicola Moorby, ‘Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.),The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/nicola-moorby-her-indoors-women-artists-and-depictions-of-the-domestic-interior-r1104359 , accessed 21 August 2013.

Guy Deghy and Keith Waterhouse, Café Royal: Ninety Years of Bohemia, Hutchinson, London 1955, p.129.

See, for example, C.R.W. Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice, Methuen, London 1937, p.58; Hugh D. Ford (ed.), Nancy Cunard: Brave Poet, Indomitable Rebel, 1896–1965, Chilton Book Co., Philadelphia 1968, p.26; Hugh David, The Fitzrovians: A Portrait of Bohemian Society, 1900–1955, Joseph, London 1988, p.112.

Nina Hamnett, Laughing Torso: Reminiscences of Nina Hamnett, Ray Long and Richard R. Smith, New York 1932.

Peter Brooker, Bohemia in London: The Social Scene of Early Modernism, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2004, p.108.

See Valerie Fehlbaum, ‘Ella Hepworth Dixon: New Woman, New Image?’, Nineteenth-Century Feminisms, vol.4, Spring–Summer 2001, pp.47–74.

See Talia Schaffer, ‘A Tethered Angel: The Martyrology of Alice Meynell’, Victorian Poetry, vol.38, no.1, Spring 2000, pp.49–61; Linda H. Peterson, Becoming a Woman of Letters: Victorian Myths of Authorship, Facts of the Market, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 2009, p.204.

Talia Schaffer notes that Woolf came to see Meynell as the emblem of everything against which she was rebelling. See Schaffer, The Forgotten Female Aesthetes: Literary Culture in Late-Victorian England, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville 2000, p.191.

NPG 2221. Reproduced at National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?search=sp&sText=Alice+Meynell&rNo=0 , accessed 27 January 2011.

Meaghan Clarke, ‘(Re)viewing Whistler and Sargent: Portraiture at the Fin-de-Siècle’, Revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, vol.30, nos.1–2, 2005, pp.74–86.

Alice Meynell, ‘A Woman in Grey’, The Colour of Life, and Other Essays, Etc., John Lane, London 1896.

Holly Pyne Connor, ‘Not at Home: The Nineteenth Century New Woman’, in Off the Pedestal: New Women in the Art of Homer, Chase, and Sargent, exhibition catalogue, Newark Museum, New Jersey 2006, p.46. See also Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings, vol.2, Yale University Press, New Haven 2002, p.122; Ellen Wiley Todd, The ‘New Woman’ Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street, University of California Press, Berkeley 1993, pp.9–11.

NPG 4439. Reproduced at National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?mkey=mw03484&search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=gwen+john&LinkID=mp02438&role=sit&rNo=0 , accessed 27 January 2011.

Alicia Foster, ‘Gwen John’s Self-Portrait: Art, Identity and Women Students at the Slade School’, in David Peters Corbett and Lara Perry (eds.), English Art 1860–1914: Modern Artists and Identity, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2000, p.176.

Denise Hooker, Nina Hamnett: Queen of Bohemia, Constable, London 1986, p.37. Like the portrait of Kerr, the cropped hair and hand-on-hip pose of Hamnett’s 1913 self-portrait emphasises her modernity. Reproduced ibid., p.29.

Reproduced ibid., p.86, and Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005 (24).

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, in London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, p.7, in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.60.

Anna Gruetzner Robins, A Fragile Modernism: Whistler and his Impressionist Followers, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2007, p.145.

Ana Parejo Vadillo, Women Poets and Urban Aestheticism: Passengers of Modernity, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2005, pp.13, 127–60.

See Andrew Stephenson, ‘Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/andrew-stephenson-questions-of-artistic-identity-self-fashioning-and-social-referencing-in-r1104367 , accessed 21 August 2013.

Meaghan Clarke is a Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of Sussex.

How to cite

Meaghan Clarke, ‘Sex and the City: The Metropolitan New Woman’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www