British Art and the Sublime

Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn

For artists throughout history the sublime has been an expression of the unknowable, and it therefore seems to have escaped definition. Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn look back at the sublime in British art and explore what it has meant in the past and how it continues to be reinterpreted today.

Debating the sublime

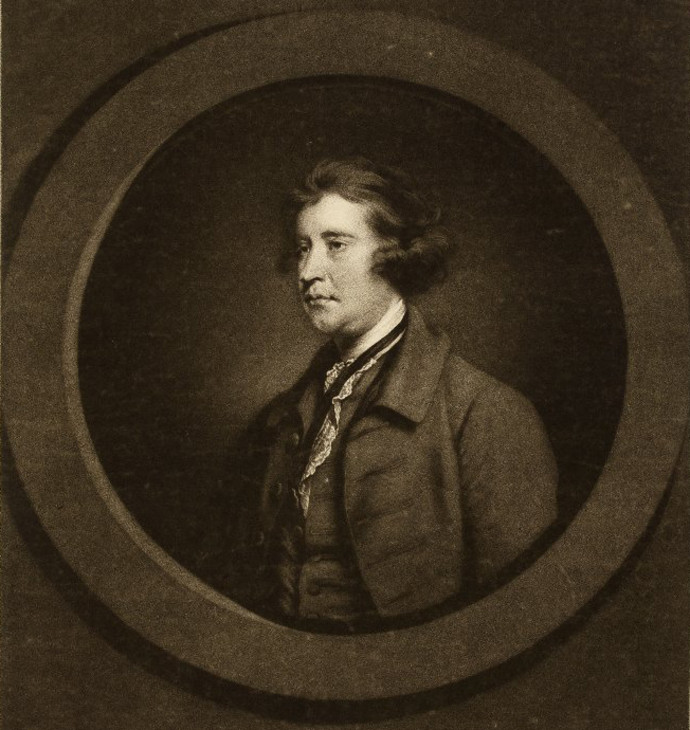

After Sir Joshua Reynolds

Portrait of Edmund Burke 1770

Mezzotint

377 x 275 mm

The British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.1

After Sir Joshua Reynolds

Portrait of Edmund Burke 1770

The British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

By about 1700 an additional theme started to develop, which was that the sublime in writing, nature, art or human conduct was regarded as of such exalted status that it was beyond normal experience, perhaps even beyond the reach of human understanding. In its greatness or intensity and whether physical, metaphysical, moral, aesthetic or spiritual, by the time of the Enlightenment, the sublime was generally regarded as beyond comprehension and beyond measurement.

It was at this point in the history of the word sublime that visual artists became deeply intrigued by the challenge of representing it, asking how can an artist paint the sensation that we experience when words fail or when we find ourselves beyond the limits of reason? The works of art that will be discussed in this introductory essay were conceived and executed in response to the challenge of painting the unpaintable. The sublime is not the only kind of unpaintable subject matter that painters engage with but it is a theme in the history of the visual arts that leads us to the heart of the imaginative process and it is a complex theme. Painters and other artists aspire to address the sublime in their art but, in addition, through their art they aim to create works that will have a sublime effect on the spectator. This essay, and indeed the scholarship that it introduces, is intended to help readers see that this is an issue with two sides: we are seeking to recognise the motivations and devices that artists employed when they painted the sublime and also to understand the response that those devices were intended to elicit.

These days the word sublime is applied in everyday language to almost anything that can be refined to the highest point, such as a perfectly executed tennis shot or a delicious sauce on a dinner plate. This is an interesting contrast with the historic past when sublime was a term that was used in art writing alongside adjectives such as ‘awful’, ‘dreadful’ and ‘terrible’, which today tend simply to denote ‘less than ideal’ but which in the 1700s were understood explicitly as expressions of awe, dread and terror, and were associated with the sublime as standard elements in aesthetic discourse. Authors who used terms like these were seeking to define and differentiate the different kinds of beauty to which visual artists should aspire – ideal, picturesque, classical, sublime and so on. Indeed, the sublime was, and remains, an important matter for visual artists on a number of levels, affecting artists’ choice of subject matter, the nature of the spectator’s response, ideas about artistic creativity as well as offering a yardstick for judging aesthetic excellence.

Analysing the sublime

Although the theory of the sublime was discussed across many western cultures, it was especially important in eighteenth-century Britain, mainly because of the increasing importance of landscape as a subject category for artists and critics and because of the impact in the eighteenth century of the best-known theory of the sublime in English, which is found in the Irishman Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, published in 1757. Edmund Burke (fig.1) was not the first philosopher to be intrigued by the power and complexity of the idea of the sublime but his account of it was exceedingly influential. He broke the idea of the sublime down into seven aspects, all of which he argued were discernible in the natural world and in natural phenomena:

Darkness – which constrains the sense of sight (primary among the five senses)

Obscurity – which confuses judgement

Privation (or deprivation) – since pain is more powerful than pleasure

Vastness – which is beyond comprehension

Magnificence – in the face of which we are in awe

Loudness – which overwhelms us

Suddenness – which shocks our sensibilities to the point of disablement

Obscurity – which confuses judgement

Privation (or deprivation) – since pain is more powerful than pleasure

Vastness – which is beyond comprehension

Magnificence – in the face of which we are in awe

Loudness – which overwhelms us

Suddenness – which shocks our sensibilities to the point of disablement

Although the phenomena on this list represent serious challenges to human equanimity, Burke argued that they were benevolent on the grounds that sublime reactions like these would lead to a kind of pleasurable or fulfilling terror. So it was that for an eighteenth-century viewer to be frightened by a sublime effect in a work of art was regarded as a positive experience. Take this passage, which reads like an entry in a Grand Tourist’s diary, but which is, in fact, taken from a novel by Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823):

They quitted their carriages and began to ascend the Alps. And here such scenes of Sublimity opened upon them as no colours of language must dare to paint ... Emily seemed to have arisen in another world, and to have left every trifling thought, every trifling sentiment, in that below: those only of grandeur and sublimity now dilated her mind and elevated the affections of her heart. 2

Referring back to Burke’s list, we can see that many Burkean tropes occur in this passage: the sudden transformative view; a sensation that is beyond expression and which impairs the intellectual faculties; the idea that contemplation of the sublime transports the spectator; and, the association of the themes of grandeur and elevation.

On the simplest level, a sublime experience while crossing the Alps is an engagement with landscape and in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain, the sublime was associated in particular with human responses to the immensity or turbulence of the natural world, as captured by landscape artists. Consequently, sublime landscape painters, especially in the Romantic period, around 1800, tended to take subjects such as towering mountain ranges, deep chasms, violent storms, rough seas, volcanic eruptions or avalanches that, if actually experienced, would be dangerous and even life-threatening. Importantly, during this same period, the relationship between the sublime and other aspects of the ‘beautiful’ was probably the key topic discussed among aestheticians, who tended to refer back to revered poets and artists of earlier periods as the examples to be emulated. Tracing sublime and beautiful tendencies was, therefore, a way of organising the history of art. For example, looking back at seventeenth-century Italy, the Romantic theorists regarded the Neapolitan painter Salvator Rosa (1615–1673) as an able exponent of the sublime, pointing out that he used landscape (to quote the artist Henry Fuseli) as ‘a vehicle of terrour [sic]’, and delighted ‘in ideas of desolation, solitude, and danger’.3 By contrast, the work of the Frenchman Claude Gelée, better known as Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), was regarded as the antithesis of sublime since it exemplified classical beauty through its formal harmony, elegance and subtle luminosity. Claude’s compositions are perhaps the antithesis of ‘disorder’, described so often in the sublime literature as a positive attribute and a potent sign of a sublime effect, for example:

A great mass of rock, thrown together by the hand of nature, with wildness and confusion, strikes the mind with more grandeur than if they had been adjusted to each other with the most accurate symmetry.4

The sublime before Edmund Burke

As was typical of his time, the origins of Burke’s vision of the sublime lay in his study of classical antiquity but his sources were radically adapted to suit the tastes of his early modern readers. Not a lot is known about the theory of the sublime in the ancient world. The key surviving ancient text was a treatise or dissertation on literary criticism, written in Greek sometime during the first century AD, of which some forty sections have survived; it is entitled Peri Hypsous (On the Sublime). The author is anonymous but by convention the work is associated with one ‘Longinus’, who seems to have been a trained rhetor (speech-maker) and was, evidently, well read in earlier pagan Greek literature but also – and unusually – familiar with the Jewish Old Testament. In recognition of its uncertain authorship we will refer to the Peri Hypsous as the work of the Pseudo-Longinus. This remarkable ancient book examines the sublime from a number of angles and cites several dozen ancient poets, dramatists, philosophers and orators to argue that the written and spoken word can have a powerful ‘transporting’ effect on its audience. To use language persuasively is, after all, the main purpose of rhetoric. Pseudo-Longinus thought that these kinds of transformative effect could best be achieved by privileging the elevated and expressive – ‘noble thoughts’ and ‘strong emotions’ – over form and structure. The book is about orally transmitted poetry rather than paintings, sculptures or any other aspect of visual culture, just as Burke’s later theories were also intended to apply across cultural fields, not just in the visual arts. Some passages by Pseudo Longinus are followed very closely in both tone and content in Edmund Burke’s essay, for example, this passage about ‘The True Sublime’ in Book 7 of the Peri Hypsous:

For by some innate power the true sublime uplifts our souls; we are filled with a proud exaltation and a sense of vaunting joy; just as though we had ourselves produced what we had heard.5

British interest in Pseudo-Longinus’ treatise seems to have started in the mid-seventeenth century when it was translated and given English titles that emphasise the key sublime theme of striving for elevation: for example, one publisher issued it as The Height of Eloquence and another as The Loftiness or Elegancy of Speech. Informed readers of Pseudo-Longinus during the eighteenth century, when the status of painting was under debate and when the painting market was dominated by portraiture, were also intrigued that the ancient authority suggested a theoretical relationship between sublime experience and history. This was significant because the standard hierarchy of the visual art genres placed portraiture lower in the canon than history, which was considered the most prestigious and demanding genre of art and distinguished from portraiture and landscape through its concern with the ideal and the heroic. The early modern theory of history painting identified its proper subject matter as coming from a restricted portfolio of acceptable and reputable literary sources, notably the Bible and classical literature. For example, Homer’s epic poems The Odyssey and The Iliad were regarded as canonical texts for history painters. Moreover, these ancient literary sources were quoted by Pseudo-Longinus, who – unusually for an author writing in Greek in the first century AD – also referred to the Book of Genesis:

So too the lawgiver of the Jews, no ordinary person, having formed a high conception of the power of the Divine Being, gave expression to it when at the very beginning of his Laws he wrote: ‘God said’ – what? ‘Let there be light: and there was light; let there be land, and there was land’ (Book 9: ‘Nobility of Soul’ referring to Genesis 1:3)

Pseudo-Longinus’ inclusion of this quotation helped establish for the early moderns the credentials of Biblical episodes as paradigms of sublimity, especially Old Testament scenes, but also the apocalyptic visions described in the New Testament’s very last book, The Revelation of St John the Divine. In addition, post-classical texts that emulated the style and subject matter of the Bible were regarded as sources of sublime subject matter in their own right, for example, the Divine Comedy, completed just before his death, by Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). Dante’s poem describes a visionary journey through hell, purgatory and paradise, and portrays vast landscapes and scenes of unimaginable terror. It became increasingly popular in England in the 1600s. It was read and admired by John Milton (1608–1674), the author of another Christian epic, Paradise Lost (completed in 1667), which was seen by the contemporary poet John Dryden (1631–1700) as ‘one of the greatest, most noble, and most sublime poems, which either this Age or Nation has produced’.6

Pseudo-Longinus wrote his book in order to instruct readers dedicated to attaining high standards in literature, which in the eighteenth century came to be known as ‘the grand style’. Being an instructive or didactic dissertation, the text of Peri Hypsous gives the reader practical advice, for example, by listing the ‘Five Sources of Sublimity’, which are described in Book 8. Confirming the long history of the sublime as a phenomenon with manifold aspects, these ‘Five Sources’ are comparable to the seven aspects of the Burkean sublime described above:

The first and most important is the ability to form grand conceptions ... Second comes the stimulus of powerful and inspired emotion ... These two elements ... are very largely innate... [third is] the proper formation of ...figures of thought and figures of speech ...[fourth is] the creation of a noble diction ...[that is] the choice of words, the use of imagery, and the elaboration of the style... The fifth source of grandeur ... is the total effect resulting from dignity and elevation (Pseudo-Longinus, ed cit 108).

But how did artists adapt a theory designed for literature to the visual arts and how did they rise to the challenge of communicating the unimaginable?

The sublime imagination

One episode that captured the imagination of John Milton’s readers was the violent encounter between Satan, Sin and Death that he described in verse in Book 2 of Paradise Lost. William Hogarth’s version of the subject (fig.2, Tate T00790) was painted in the late 1730s, some twenty years before Burke’s treatise was published and the picture has been seen as a forerunner of a major trend in later eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British art, namely, the ‘horrific-sublime’. Hogarth’s painting illustrates Pseudo-Longinus’ first dictum, the requirement for the artist to employ powerful and inspired emotion. A complementary issue – one that reminds us that Hogarth was finding his way as a history painter at this stage in his career – is whether his painting also illustrates Pseudo-Longinus’ fifth dictum, that the work should have the dignity and elevation to support the grandeur of its theme. Some later critics – enthusiasts for the pure rigour of the Burkean model of the sublime – found fault with Hogarth’s characteristic and exploratory mixture of the ‘grotesque’ and the ‘elevated’. In fact, this was a criticism that was often levelled at works of ‘historical’ art in the eighteenth century, even at Shakespeare, who was not regarded as a sublime dramatist in the purest sense, despite the unrivalled power of his tragedies and histories. For most of the 1700s admiration for Shakespeare was qualified, especially in terms of its sublime impact. Some critics felt that the psychological potential of juxtaposing of the sublime and the ridiculous could itself create a sublime outcome. For example the way that Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), in his painting Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers ?exhibited 1812 (fig.3, Tate T00733) paints the tense exchange between Lady Macbeth and her husband, posing awkwardly and almost comically overwrought but still clutching the bloodied daggers with which he has murdered Duncan, smacks of the ‘darkness’, ‘obscurity’ and ‘privation’ recommended by Burke and reminds us of the Burkean precept that terror is the strongest of the passions and therefore the passion best suited to produce a sublime effect.

William Hogarth 1697–1764

Satan, Sin and Death (A Scene from Milton's 'Paradise Lost') c.1735–40

Oil paint on canvas

support: 619 x 745 mm; frame: 803 x 935 x 80 mm

Tate T00790

Purchased 1966

Fig.2

William Hogarth

Satan, Sin and Death (A Scene from Milton's 'Paradise Lost') c.1735–40

Tate T00790

Henry Fuseli 1741–1825

Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers ?exhibited 1812

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1016 x 1270 mm; frame: 1213 x 1454 x 100 mm

Tate T00733

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1965

Fig.3

Henry Fuseli

Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers ?exhibited 1812

Tate T00733

The idea that sublime art could not be achieved by slavishly following rules, but rather was an experience that existed above and beyond rules in the realm of artistic imagination, was first explored by a predecessor of Burke’s, the painter and critic Jonathan Richardson (1665–1745) in his book An Essay on the Theory of Painting (1715). This was the first English publication to encourage artists to aspire to the sublime and in Richardson’s argument we start to hear the claim – one that recurs regularly through the 1700s – that the sublime is not only desirable but is indeed the highest level of artistic attainment. As Richardson put it: ‘the Sublime, where-ever ’tis found, though in Company with a thousand Imperfections, transports and captivates the Soul; the Mind is filled, and satisf’d’7. According to Richardson, what made Michelangelo a paradigm of perfection for modern (post-antique) art was the fact that he was an explicitly sublime artist rather than simply the supreme history painter. This viewpoint was reinforced by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), whose longstanding admiration for the ‘divine’ Michelangelo was restated in extravagant terms in 1790 in the last of his famous series of presidential lectures (or ‘Discourses’) to the Royal Academy. Reynolds describes Michelangelo as sublime over-and-over again despite having a concern that the study of Michelangelo presented dangers to the aspiring student since his art required sophistication and experience on the part of the onlooker and critic. In terms of practice rather than theory, in the hands of an accomplished portraitist such as Reynolds, sublime effects could be used to enhance the narrative and dramatic content, especially the Burkean device of ‘obscurity’, for example, in the swirling smoky battleground behind Admirable Viscount Keppel 1780 (Tate, N00886, 1780) or in other mature portraits.

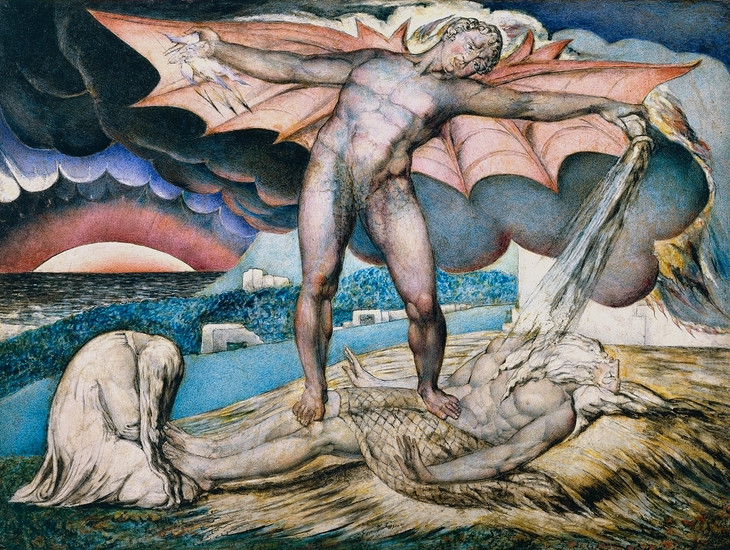

William Blake 1757–1827

Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils c.1826

Pen and ink and tempera on mahogany

support: 326 x 432 mm; frame: 380 x 483 x 37 mm

Tate N03340

Presented by Miss Mary H. Dodge through the Art Fund 1918

Fig.4

William Blake

Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils c.1826

Tate N03340

Frederic, Lord Leighton 1830–1896

And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It exhibited 1892

Oil paint on canvas

support: 2286 x 2286 mm

Tate N01511

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Fig.5

Frederic, Lord Leighton

And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It exhibited 1892

Tate N01511

Contemporarily with Reynolds, the artist, poet and visionary, William Blake (1757–1827) was, by contrast, unhesitating in his praise for Michelangelo, hailing him for his selfless, spiritual dedication to art and for showing a level of commitment that paralleled his own. Blake produced hundreds of drawings, watercolours and paintings on biblical themes, some of which were indebted to Michelangelo, in particular the much admired Last Judgement 1537–41 in the Sistine Chapel. In Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils 1826 (fig.4, Tate N03340), an extraordinary scene of Burkean ‘privation’ or suffering, Blake explores his own idiosyncratic interpretation of what he called ‘the sublime of the Bible’.8 Through the nineteenth century, the emulation of Michelangelo’s sculptural and highly expressive figurative compositions, usually with the barest possible landscape setting, was a means for British artists to engage with the aesthetic of the sublime. A monumental painting by Frederic Leighton (1830–1896), And the Sea Gave Up the Dead which Were In It exhibited 1892(fig.5, Tate N01511), is just such a Michelangelesque work on a subject – the Last Judgement – that by very definition, has never been witnessed and which, therefore, defies the imagination.

Sublime spectacle

During the later eighteenth century, the precepts set out in Burke’s treatise became more and more influential as they entered the cultural mainstream. Not all his recommendations could be readily converted from their literary context to become applicable for painters but artists evidently seized on Burkean aspirations about grandeur and profundity of impact on the spectator. For Pseudo-Longinus grandeur or greatness had been virtually synonymous with the sublime; in around 1800 British painters started to explore how viewers could be overwhelmed or transported by greatness, which in itself was understood in a number of different ways. Sublime grandeur in Blake is about conception but for other artists, the material scale or size of the work was, in itself, the distinguishing factor. The painting by James Ward (1769–1859) of Gordale Scar in North Yorkshire (fig.6, Tate N01043), is on a scale – over three metres high by over four metres wide – which is colossal and unprecedented at that date in British landscape painting. It was looked upon ‘with Awe and a kind of Reverential Expectation’ by visitors to the Royal Academy when it was exhibited there in 1815. Ward manipulates the scale of the cattle and also uses contrasts of light and shade to emphasise the primordial bank of limestone cliffs. Gordale Scar was but one of a number of massive paintings that started to be exhibited in public from the 1780s onwards, including works by Benjamin West (1738–1820), Henry Fuseli, Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786–1846), John Martin (1789–1854), Francis Danby (1793–1861) and others.9 The subjects of these works were invariably histories or historical landscapes and were often on show at the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy, which was from 1769 the nation’s premier public space for exhibiting contemporary art, especially art that aspired to create sublime effects. Because of the crowded walls, with paintings hung frame-to-frame, artists had to vie with one another for the visitors’ attention and the exploitation of scale and the manipulation of sublime effects became essential means of securing notice. Within visual culture more broadly, these questions of scale and effect were not restricted to the high art of painting. In the world of theatre and popular entertainment, panoramas, dioramas and ‘Phantasmagorias’ were invented to trade specifically on pleasurable awe and horror. For example, the Royal Academician Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812), renowned for his highly dramatic landscapes and battle scenes such as An Avalanche in the Alps 1803 (fig.7, Tate T00772), also worked for the actor-manager David Garrick at the Drury Lane Theatre as a set designer and invented the Eidophusikon, an animated stage-set first deployed in 1781 and intended to generate sublime sensations in its audience.

James Ward 1769–1859

Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale) ?1812–14, exhibited 1815

Oil paint on canvas

support: 3327 x 4216 mm

Tate N01043

Purchased 1878

Fig.6

James Ward

Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale) ?1812–14, exhibited 1815

Tate N01043

Philip James De Loutherbourg 1740–1812

An Avalanche in the Alps 1803

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1099 x 1600 mm; frame: 1562 x 2052 x 175 mm

Tate T00772

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1965

Fig.7

Philip James De Loutherbourg

An Avalanche in the Alps 1803

Tate T00772

A second level of grandeur could, as we have seen, be attained through the appropriate choice of subject matter, for example, epic scenes from history using orthodox biblical or classical sources and, increasingly as time passed, using modern subjects from national literature and history. This development took place in the wake not only of the publication of Burke’s treatise but also of the instigation in 1760 of art exhibitions at the Society of Artists designed to attract the public in large crowds. The series of paintings and prints by George Stubbs (1724–1806) depicting a violent encounter between a horse and a lion (Figs.8, 9 and 10; Tate T06869, T01192 and T02058), two examples of which were exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1763, was a direct response to Burke’s promotion of the theme of ‘Frightening Nature’ and offered a thrilling visual experience aimed at appealing to a broad, less ‘high-minded’ public, able to sympathise with the terror of the scene without having to know classical languages or any particular highbrow literary source.

George Stubbs 1724–1806

Horse Frightened by a Lion ?exhibited 1763

Oil on canvas

unconfirmed: 705 x 1019 mm; frame: 885 x 1208 x 85 mm

Tate T06869

Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1994

Fig.8

George Stubbs

Horse Frightened by a Lion ?exhibited 1763

Tate T06869

George Stubbs 1724–1806

Horse Attacked by a Lion 1769

Enamel on copper

support: 241 x 283 mm; frame: 514 x 560 x 74 mm

Tate T01192

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1970

Fig.9

George Stubbs

Horse Attacked by a Lion 1769

Tate T01192

George Stubbs 1724–1806

Horse Devoured by a Lion ?exhibited 1763

Oil paint on canvas

support: 692 x 1035 mm; frame: 897 x 1243 x 80 mm

Tate T02058

Purchased 1976

Fig.10

George Stubbs

Horse Devoured by a Lion ?exhibited 1763

Tate T02058

Joseph Wright of Derby 1734–1797

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples c.1776–80

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1220 x 1764 mm; frame: 1461 x 1941 x 95 mm

Tate T05846

Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, Friends of the Tate Gallery, and Mr John Ritblat 1990

Fig.11

Joseph Wright of Derby

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples c.1776–80

Tate T05846

Richard Wilson 1713–1782

Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris ?exhibited 1774

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 730 mm

Tate N05596

Presented by Sir Edward Marsh 1945

Fig.12

Richard Wilson

Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris ?exhibited 1774

Tate N05596

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

The Shipwreck exhibited 1805

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1705 x 2416 mm; frame: 2085 x 2795 x 235 mm

Tate N00476

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.13

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Shipwreck exhibited 1805

Tate N00476

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 1222 mm; frame: 1120 x 1425 x 105 mm

Tate T01585

Purchased 1972

Fig.14

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796

Tate T01585

Sublime effect achieved a high point of theatricality in the work of John Martin: a blood-red sun contrasts with a single bolt of white lightning that rips across the scene of devastation in The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3 (fig.15, Tate N05613). In The Last Judgement (fig.16, Tate T01927), the damned topple into a black abyss, above which Jesus Christ is enthroned, bathed in ‘celestial’ light. Infinity is the theme of the second part of the trilogy, The Plains of Heaven (fig.17, Tate T01928), with its extraordinary luminosity and its ethereal representation of the kingdom of God in the form of a classical city in the background. Martin had introduced this new and extremely popular form of apocalyptic sublime in the 1820s, achieving considerable acclaim in Britain, France and later the United States (the Last Judgement trilogy toured to New York in 1856). However, the ambition of Martin’s compositions could equally provoke derision and alarm: in the late 1820s, the American landscape painter Thomas Cole, an admirer of both Martin and Turner, was warned by an art critic against the pitfalls of being seen to imitate ‘Pandemonium Martin’.11 Pandemonium or not by the 1840s, in the hands of Martin and others, by the 1840s, the pictorial language of the sublime in British landscape painting was moving towards the formulaic and clichéd.

John Martin 1789–1854

The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1965 x 3032 mm; frame: 2400 x 3470 x 175 mm

Tate N05613

Purchased 1945

Fig.15

John Martin

The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3

Tate N05613

John Martin 1789–1854

The Last Judgement 1853

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1968 x 3258 mm; frame: 2400 x 3685 x 175 mm

Tate T01927

Bequeathed by Charlotte Frank in memory of her husband Robert Frank 1974

Fig.16

John Martin

The Last Judgement 1853

Tate T01927

John Martin 1789–1854

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1988 x 3067 mm; frame: 2415 x 3485 x 175 mm

Tate T01928

Bequeathed by Charlotte Frank in memory of her husband Robert Frank 1974

Fig.17

John Martin

The Plains of Heaven 1851–3

Tate T01928

William Dyce 1806–1864

Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 889 mm; frame: 950 x 1200 x 125 mm

Tate N01407

Purchased 1894

Fig.18

William Dyce

Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60

Tate N01407

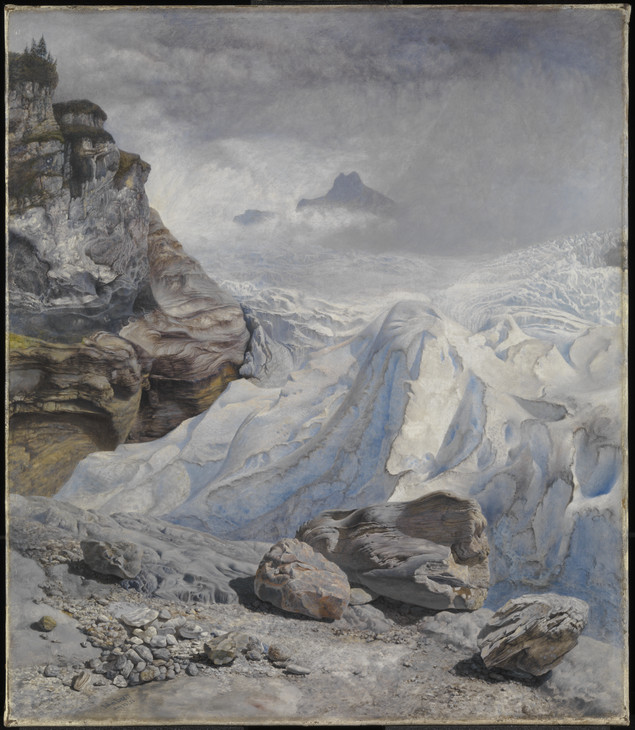

John Brett 1831–1902

Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

Oil paint on canvas

support: 445 x 419 mm; frame: 690 x 603 x 71 mm

Tate N05643

Purchased 1946

Fig.19

John Brett

Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

Tate N05643

Dawning realisation

That this enquiry had a deeply spiritual dimension – a search for a higher truth – and a sublime aspect, is demonstrated most clearly in Thomas Seddon’s Jerusalem 1854–5 (Tate N00563). Seddon and his friend William Holman Hunt had travelled to the Holy Land in the 1850s with the express purpose of seeking inspiration to undertake a subsequent reform of British religious art. Landscape painting in the mode adopted by Seddon was aimed at a new aspect of sublimity, one quite different to earlier traditions of Burkean obscurity and the titanic pandemonium of John Martin. By studying the people and natural landscapes around Jerusalem, which were assumed to have remained unchanged since the time of Jesus Christ, Seddon combined an almost forensic attention to the specifics of the location with powerful biblical allegory. For example, the painting shows the Mount of Olives as an element in the landscape although anyone aware of the Gospel narrative would recognise it as the site of Christ’s temptation and despair after the Last Supper. Furthermore, since there was a tradition that identified the Vale of Jehoshaphat, outside Jerusalem, as the site for the Last Judgement, we can interpret the inclusion of the shepherd with his sheep and goats, as a reference to Jesus’ own description of the end of days. This new mode of sublime reference is the sublimity of dawning realisation through symbolism.

Seddon’s Jerusalem was executed a few years prior to the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), with its famous thesis based on his meticulous observations as a naturalist. Nevertheless, the metaphorical and even visionary language that Darwin used to set out his arguments drew inspiration from the Romantic sublime. The sublimity of his scientific and literary achievement lies in the reader’s dawning realisation of the full implications of the theories of evolution and natural selection, which were so profound and far-reaching that they fundamentally challenged near universal perceptions of the relationship between nature and humankind. In ways that parallel the time it takes for the true scale of John Martin’s titanic visions to dawn upon the viewer, a reading of the On the Origin of Species slowly unfolds the profound antiquity of the earth. The dramatic life cycles of the species that inhabited that world could also be presented to elicit sublime effects. George Stubbs’s visions of savage, impersonal nature, such as Horse Attacked by a Lion 1769 (fig.20, T01192), is concerned with portraying the struggle for existence and, closer to Darwin’s own day, the paintings by Edwin Landseer (1802–73) of hunted deer and stags in the Scottish Highlands, for example, Deer and Deer Hounds in a Mountain Torrent (‘The Hunted Stag’) ?1832, (fig.21, Tate N00412), have been seen to embody the paradox of ‘man as nature’s chief aggressor’ and ‘man as anguished spectator of nature’s sufferings’.13 Critical responses like these echo some of the qualities that Burke found in the sublime – vastness or privation (with pain more powerful than pleasure) or the suddenness that shocks the sensibilities.

George Stubbs 1724–1806

Horse Attacked by a Lion 1769

Enamel on copper

support: 241 x 283 mm; frame: 514 x 560 x 74 mm

Tate T01192

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1970

Fig.20

George Stubbs

Horse Attacked by a Lion 1769

Tate T01192

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer 1802–1873

Deer and Deer Hounds in a Mountain Torrent ('The Hunted Stag') ?1832, exhibited 1833

Oil paint on canvas laid on wood

support: 405 x 908 mm

Tate N00412

Presented by Robert Vernon 1847

Fig.21

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer

Deer and Deer Hounds in a Mountain Torrent ('The Hunted Stag') ?1832, exhibited 1833

Tate N00412

The Hon. John Collier 1850–1934

The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson exhibited 1881

Oil paint on canvas

support: 2140 x 1835 mm

Tate N01616

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1881

Fig.22

The Hon. John Collier

The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson exhibited 1881

Tate N01616

Moving closer to our own day, twentieth-century historical subjects – World Wars, revolution and famine – have provided painters with sublime subject matter with connotations of futility, ruin and waste. In a letter to his wife dated 1917, the artist-soldier Paul Nash attempted to convey the horrors of the battlefield and in so doing touched on the sublime theme of indescribability: the devastation is ‘unspeakable, utterly indescribable’, he writes, alluding to a ‘Godless’, ‘blasphemous’, ‘nightmare’ of a landscape ‘more conceived by Dante or [Edgar Allan] Poe than by nature’.15 The following year William Orpen, an official war artist, painted Zonnebeke (fig.23, Tate T07694), representing the battlefield not only with frankness and brutal realism but also for the sheer magnitude of what he had witnessed and in so doing resorted to the ‘language’ of the sublime in a vision that approximates to that of a biblical apocalypse by Martin or Turner’s Death on a Pale Horse c.1825–30 (fig.24, Tate N05504)16.

Sir William Orpen 1878–1931

Zonnebeke 1918

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 762 mm; frame: 820 x 953 x 75 mm

Tate T07694

Presented by Diana Olivier 2001

Fig.23

Sir William Orpen

Zonnebeke 1918

Tate T07694

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Death on a Pale Horse (?) c.1825–30

Oil paint on canvas

support: 597 x 756 mm; frame: 776 x 940 x 68 mm

Tate N05504

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.24

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Death on a Pale Horse (?) c.1825–30

Tate N05504

Architecture

As we have seen, the first reference to the Bible as a source of sublimity was found in Pseudo-Longinus’s Peri Hypsous, which explores the rhetorical power of the word. In this essay we have explored the application of these and derivative ideas proposed by Burke and other Enlightenment theorists to the art of painting. However, they are also applicable to architecture and indeed to other forms of visual culture such as cinema. For example, buildings of many styles and periods have emphasised grandeur of scale and conception and have been designed to excite, elevate and ultimately overpower their audiences. In vast interior spaces such as the Vatican basilica of St Peter’s or the Roman temple dedicated to the Pantheon, the relationships of scale and human size are so disparate that the capacity to measure space can become impaired. This was an aspect of the vast interior of St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London that was exploited in 2009 by the artist Bill Viola, who was commissioned to create two altarpieces in the form of video installations to be placed on either side of the High Altar (due for completion in 2012). Viola’s work, which has been described as sublime, focuses on ‘universal human experiences – life, death and rebirth’,17 drawing particular inspiration from devotional art.

Douglas Gordon is another contemporary artist whose output responds to many of the themes discussed in this essay, from the eternal struggle played out in the video installation A Divided Self I and II 1996 and the stream of personal fears represented in the wall texts of From God to Nothing 1996 (FRAC Languedoc-Roussillon), to the sequential photographic images entitled Monster 1996–7 and Monster Reborn 1996/2002, in which the artist seems to cast himself as a latter-day Jekyll and Hyde. In 2009 Gordon was commissioned to create a site-specific work at Tate Britain in the context of the research project that lies behind this website. It was to be installed in the Octagon and alongside a display of historic works on sublime themes in the adjacent gallery. The Baroque revival spaces of this part of Tate Britain were utilised by Gordon, who animated the architecture with a supremely complex yet cohesive installation of over eighty passages of text entitled Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from 1989... 2010. These texts were applied directly to the stone surfaces of walls, piers, floors and ceiling. On one level, the effect seems to articulate Gordon’s idea of art operating as ‘a dialogue between artist and viewer’; hence many of the texts address us directly, employing ‘I’, ‘You’ and ‘We’.18 On another, the assemblage as a whole underlines the artist’s fascination with language and its potential for ambiguity, obscurity and multiple meanings. As the title suggests, the origins and style of these texts are wide-ranging, both personal and universal. Some have a rhetorical or biblical tone, such as the declamatory ‘We Are Evil’ writ large on the floor of the Octagon, or the contemplative rendering of ‘Read the Word ... Hear the Voice’ on the ceiling in the adjacent gallery. The latter was positioned opposite, and thus in dialogue with, another text set as an ellipse that quotes one of the sayings of Jesus Christ, ‘truly I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise’, spoken during his crucifixion, as related in the Gospel of St Luke (23:34) and here installed in powerful juxtaposition with John Martin’s Last Judgement trilogy, then hanging in the nearby display. Other texts are quotations from popular culture but with appropriately grave associations, for example, ‘This May Be The Last Time’ on the domed ceiling, a line taken from a song recorded by The Rolling Stones in 1965.

The act of looking up into the dome to engage with Gordon’s work takes us back to the core definitions of the word sublime discussed at the start of this introductory essay: that is, something weighty, set up high or raised aloft. The dome itself has powerful cultural and spiritual resonances, being a signature feature of many European and Middle Eastern styles of architecture – ancient, Byzantine, Renaissance, Baroque and neoclassical – occurring in temples, churches, mosques and endless kinds of public buildings, including Tate. Had he been concerned with architecture, Pseudo-Longinus would perhaps have understood the dome as an archetypal form – lofty, often obscurely lit, immeasurable in its dimensions, incomprehensible in its stresses and structures and magnificent in its effects. In contemporary culture, the wonder expressed by visitors to London as they gaze aloft at the summit of the Shard obscured by cloud is but one communal expression of a sublimity found in visual experience. The possibilities for the sublime continue to be beyond enumeration and the material that follows offers but a taste of sensations that will remain beyond description and comprehension.

Notes

Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer, American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States 1820–1880, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2002, p.12.

Longinus 'On the Sublime' in Classical Literary Criticism, trans. by Penelope Murray and T. S. Dorsch, London 2000, p107.

Quoted in Mark Hallett and Christine Riding, Hogarth, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2006, p.44.

Carol Gibson-Wood, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment, New Haven and London 2000, p.174.

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Part Two, Section VIII

Quoted in Robert Hewison, Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 2000, p.218.

Diana Donald and Jane Munro (eds.), Endless Forms: Charles Darwin, Natural Science and the Visual Arts, New Haven and London 2009, pp.91–2.

Acknowledgements

This essay, revised by Nigel Llewellyn, is based upon the text of Christine Riding’s pamphlet, Art and the Sublime: Terror, Torment and Transcendence, which was published to accompany the collection display at Tate Britain 2009–10.

How to cite

Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn, ‘British Art and the Sublime’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013, https://www