From the entry

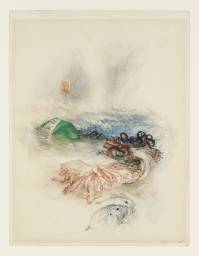

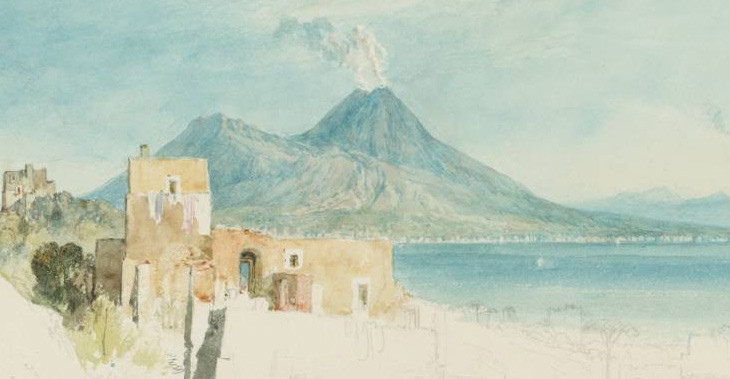

Between 1830 and 1839, Turner produced 150 vignette illustrations to be engraved for publication in works of poetry and literature. The list of authors whose texts Turner embellished includes Lord Byron (1788–1824), Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), John Milton (1608–1674), Samuel Rogers (1763–1855), Thomas Campbell (1777–1844), and Thomas Moore (1779–1852). The Turner Bequest contains nearly complete collections of finished illustrations for Turner’s two most successful vignette series, those for Samuel Rogers’s Italy (1830) and Poems (1834). In addition, the Bequest holds large groups of preliminary studies for both The Poetical Works of Thomas Campbell (1837) and Thomas Moore’s The Epicurean (1839), as well a small body of miscellaneous vignette studies, some of them relating to The Poetical Works of John Milton (1835). The term vignette (literally ‘little vine’) originally referred to a small ...

Watercolours related to Rogers’s Italy

D27518–D27519; D27523; D27525–D27526; D27530–D27531; D27539; D27604–D27605; D27609; D27612; D27618–D27624; D27660–D27678; D27680–D27684; D27710; D41487

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 1–2; 6; 8–9; 13–14; 22; 87–88; 92, 95; 101–107; 143–161; 163–167; 193; verso of 164

D27518–D27519; D27523; D27525–D27526; D27530–D27531; D27539; D27604–D27605; D27609; D27612; D27618–D27624; D27660–D27678; D27680–D27684; D27710; D41487

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 1–2; 6; 8–9; 13–14; 22; 87–88; 92, 95; 101–107; 143–161; 163–167; 193; verso of 164

Watercolours related to Rogers’s Poems

D20817; D25343; D27527; D27529; D27532–D27536; D27578; D27582; D27607–D27608; D27610–D27611; D27616–D27617; D27625; D27679; D27685–D27709; D27711–D27721; D41513; D40175

Turner Bequest CCXXVII a 14; CCLXIII 221; CCLXXX 10; 12; 15–19; 61; 65; 90–91; 93–94; 99–100; 108; 162; 168–192; 194–204; verso of 175; verso of 197

D20817; D25343; D27527; D27529; D27532–D27536; D27578; D27582; D27607–D27608; D27610–D27611; D27616–D27617; D27625; D27679; D27685–D27709; D27711–D27721; D41513; D40175

Turner Bequest CCXXVII a 14; CCLXIII 221; CCLXXX 10; 12; 15–19; 61; 65; 90–91; 93–94; 99–100; 108; 162; 168–192; 194–204; verso of 175; verso of 197

Sketches and inscriptions in an 1827 copy of Rogers’s Poems

D36330

Turner Bequest CCCLXVI

D36330

Turner Bequest CCCLXVI

Watercolours related to Poetical Works of Thomas Campbell

D25419; D27522; D27524; D27528; D27556–D27577; D27579–D27581; D27583–D27589; D27591–D27593; D27603; D27606; D27638; D27654; D27726

Turner Bequest CCLXIII 296, CCLXXX 5; 7; 11; 39–60; 62–64; 66–72; 74–76; 86; 89; 121; 137; 209

Watercolours related to Thomas Moore, The Epicurean, a Tale, and Alciphron

D27594; D27599; D27630–D27634; D27636–D27637; D27639–D27651; D27655

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 77; 82; 113–117; 119–120; 122–134; 138

D25419; D27522; D27524; D27528; D27556–D27577; D27579–D27581; D27583–D27589; D27591–D27593; D27603; D27606; D27638; D27654; D27726

Turner Bequest CCLXIII 296, CCLXXX 5; 7; 11; 39–60; 62–64; 66–72; 74–76; 86; 89; 121; 137; 209

Watercolours related to Thomas Moore, The Epicurean, a Tale, and Alciphron

D27594; D27599; D27630–D27634; D27636–D27637; D27639–D27651; D27655

Turner Bequest CCLXXX 77; 82; 113–117; 119–120; 122–134; 138

Miscellaneous Vignette Studies

D25465; D25466; D27520–D27521; D27537; D40315; D27540–D27541; D40316; D27542; D27590; D27597–D27598; D27601; D27613–D27615; D27635; D27652–D27653; D27657–D27659; D36159

Turner Bequest CCLXIII 342–343; CCLXXX 3–4; 20; verso of 20; 23–24; verso of 24; 25; 73; 80–81; 84; 96–98; 118; 135–136; 140–142; CCCLXIV 302

D25465; D25466; D27520–D27521; D27537; D40315; D27540–D27541; D40316; D27542; D27590; D27597–D27598; D27601; D27613–D27615; D27635; D27652–D27653; D27657–D27659; D36159

Turner Bequest CCLXIII 342–343; CCLXXX 3–4; 20; verso of 20; 23–24; verso of 24; 25; 73; 80–81; 84; 96–98; 118; 135–136; 140–142; CCCLXIV 302

Between 1830 and 1839, Turner produced 150 vignette illustrations to be engraved for publication in works of poetry and literature. The list of authors whose texts Turner embellished includes Lord Byron (1788–1824), Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), John Milton (1608–1674), Samuel Rogers (1763–1855), Thomas Campbell (1777–1844), and Thomas Moore (1779–1852). The Turner Bequest contains nearly complete collections of finished illustrations for Turner’s two most successful vignette series, those for Samuel Rogers’s Italy (1830) and Poems (1834). In addition, the Bequest holds large groups of preliminary studies for both The Poetical Works of Thomas Campbell (1837) and Thomas Moore’s The Epicurean (1839), as well a small body of miscellaneous vignette studies, some of them relating to The Poetical Works of John Milton (1835).

The term vignette (literally ‘little vine’) originally referred to a small ornamental printer’s device of grapes and vine leaves. By the nineteenth century, it had gained its modern meaning, namely a small scene, often borderless, that is integrated into the text, usually as a head- or tail-piece.1 John Landseer elaborated on the function of the device in his Lectures on the Art of Engraving (1807), describing it as a: ‘sort of midsummer-night’s dream, where Fancy, unrestrained by time or place, indulges in the revelry of fairy fiction:– But, whether its subject be a stern and stubborn fact; or a mere painter’s reverie; the objects introduced should always be of a subordinate and accessory kind, and the main subject of the work should never be thus represented.’2

The first decades of the nineteenth century saw a dramatic increase in the market for illustrated books of literature, topography and antiquities. The publication of large editions was made possible by the innovation of steel engraving, which came into use in the 1820s. The hardness of steel meant that engraved plates could carry an unprecedented degree of detail and variety of tones while also yielding an enormous number of fair impressions, although the disadvantage was that it was a more laborious, and therefore more expensive metal to engrave than copper. The aesthetic advantages of steel engraving are nowhere seen more clearly than in the prints made after Turner’s vignette illustrations, particularly those for Rogers’s poems. W.G. Rawlinson would later write: ‘It is doubtful if the ethereal beauty and delicacy of the famous illustrations to Rogers’s Poems and Italy could have been obtained from copper. Certainly they would have vanished with the first few impressions printed.’3

Although Turner’s work on Rogers’s poems marked his first significant foray into literary illustration, he had long been involved in the production of watercolours for engraving. By 1830, he had already built strong working relationships with a number of highly skilled engravers and had developed a significant understanding of the engraving process. Turner is often said to have fostered a ‘school’ of engravers, which included John Pye (1782–1874), Henry Le Keux (1787–1868), Edward Goodall (1795–1870), Robert Wallis (1794–1878) and William Miller (1796–1882). All of these men engraved at least some of Turner’s vignette illustrations, though Goodall was undoubtedly the most prolific contributor. He engraved a large number of plates for Italy and Poems, as well as all the plates for The Epicurean and all but three of those for Campbell’s Poetical Works.

Turner is famous for having worked closely with his engravers throughout the lengthy process of translating his designs from paper to print. Rawlinson observed that ‘probably no painter before him – unless possibly Rubens – ever so completely controlled the engraving of his own pictures, or ever so set himself to educate the engravers who worked for him; certainly none ever bestowed the same infinite pains on every detail of every plate.’4 Turner would review trial proofs of each vignette, marking, or ‘touching,’ them with further instructions to the engraver. This process was repeated at least once, and often two, or even three times before the prints were approved for publication.

Turner’s deep involvement in the engraving of his works stemmed in large part from his appreciation of the complexity of the process. Rather than conceiving of engraving as a form of straightforward imitation, he viewed it as an act of translation: ‘Engraving is or ought to be a translation of a Picture, for the nature of each art varies so much in the means of expressing the same objects, that lines become the language of colours.’5 This statement sheds some light on Turner’s apparently counter-intuitive decision to execute his vignettes in colour knowing all the while that they would be published in black and white. The task of the engraver was to capture the mood and effects of Turner’s design in the tones and textures of his own medium.

The bright colouring of the vignettes was often at odds with contemporary sensibilities. Rawlinson observed that ‘many are so unnatural or exaggerated in colour that they strike an unpleasant note.’6 This criticism may help to explain why contemporaries ascribed a relatively low value to the original vignette drawings. Thomas Campbell encountered unexpected difficulties when he attempted to find a buyer for Turner’s illustrations: ‘My illustrated edition was no sooner out than I found myself in a mess about disposing of the drawings ... I had been told that Turner’s drawings were like bank notes, that would fetch always the price paid for them, but when I offered them at £300, I could get no purchaser.’7 Samuel Rogers also observed in reference to Turner’s vignettes for Italy and Poems that ‘the truth is they were of little value as drawings.’8 However, given the praise lavished on Turner’s illustrations (often at the expense of Rogers’s poetry), this remark may also reflect a degree of resentment on the part of the poet.

In truth, it was the engraved version of Turner’s vignettes that brought the artist so much acclaim. These were the images that readers of his illustrated books saw, and these were the images that Turner set out to create. The watercolour studies, though beautiful in their own right, were primarily conceived as the first step in the production of a fine engraved image. It is therefore unsurprising that the engraved vignettes have been so intensely admired. Rawlinson considered them to be more beautiful than the original watercolours.9 However, the magnitude of Turner’s achievement was perhaps best described by the art critic P.G. Hamerton:

Of all the artists who ever lived I think it is Turner who treated the vignette most exquisitely, and if it were necessary to find some particular reason for this, I would say that it may have been because there was nothing harsh or rigid in his genius, that forms and colours melted into each other tenderly in his dream world, and that his sense of gradation was the most delicate ever possessed by man. If you examine a vignette by Turner round its edges, if you can call them edges, you will perceive how exquisitely the objects come out of nothingness into being, and how cautiously, as a general rule, he will avoid anything like too much materialism in his treatment of them until he gets well towards the centre ... Turner’s [vignettes] never seem to be shaped or put on the paper at all, but we feel as if a portion of the beautiful white surface had in some wonderful way begun to glow with the light of genius.10

The cataloguing of watercolours in the Turner Bequest related to Turner’s vignette illustrations (Turner Bequest CCLXXX) is as follows: watercolours related to Rogers’s Italy (1830); watercolours related to Rogers’s Poems (1834); watercolours related to Campbell’s Poetical Works (1837); watercolours related to Moore’s The Epicurean, a Tale, and Alciphron (1839); and miscellaneous studies.

Note: Following ongoing research across the Bequest, the following works have been introduced into this section: Tate D20817, D25343, D25419, D36159, D36330 (Turner Bequest CCXXVII a 14, CCLXIII 221, 296, CCCLXIV 302, CCCLXVI). They are noted individually in the checklists setting out the various projects at the beginning of this Introduction, which otherwise remains unchanged.

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner’s Vignettes and the Making of Rogers’ “Italy” ’, Turner Studies, vol.3, no.1, 1983, p.3.

From Turner’s second lecture on perspective, circa 1810. Quoted in John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth, New York 1969, p.196.

How to cite

Meredith Gamer, ‘Vignette Watercolours c.1826–1842’, August 2006, revised by Matthew Imms, September 2016, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www