The British Idea of Italy in the Age of Turner

David Laven

Surveying a broad range of early nineteenth-century texts – including travel guidebooks, plays, poems and personal letters – this paper reveals how the observations and opinions of influential figures such as Lord Byron, Ugo Foscolo and Lady Morgan filtered into the British imagination and shaped views of Italy’s history, culture and politics.

For most of Turner’s adult life, until he reached the age of forty, British citizens were unable to travel freely across great swathes of Europe. Two decades of almost constant military and political conflict with revolutionary and Napoleonic France meant that those parts of Europe under direct French control, or in the hands of France’s satellites and allies, were effectively closed to Britons. The Italian peninsula was no exception: before 1815 access to mainland Italy was extremely limited. Even regions of Italy controlled by sympathetic regimes were often inaccessible, or were considered too vulnerable to French attack to make them attractive destinations.1 In contrast with most of the eighteenth century, an era when Italy had thronged with well-heeled grand tourists, and when most Italian states had welcomed British merchants, diplomats and scholars, during the first decade and a half of the nineteenth century those Britons who reached Italy did so principally as members of military expeditions, as prisoners of war, or occasionally as blockade runners.2

In the Napoleonic era it was only during the year’s peace that followed the Treaty of Amiens of March 1802 that the numbers traversing the Channel significantly increased. Turner himself took advantage of this lull in otherwise near continuous fighting to visit France and Switzerland. And he crossed for the first time into Italy, although he travelled only as far as the Val d’Aosta. Relatively few of those British who rushed to take advantage of renewed access to Italy published accounts of their travels. The most famous were the work of the Anglo-Irish Catholic priest and school master John Chetwode Eustace, and that of the Scottish school master Joseph Forsyth. Significantly, neither Eustace’s A Tour Through Italy (1813) nor Forsyth’s Remarks on Antiquities, Arts, and Letters during an Excursion in Italy (1813) was published until the very eve of Napoleon’s defeat, when the prospect of continental travel once again seemed feasible for civilians.3 While many later travellers had recourse to Eustace, many lambasted him: Byron mocked him, and the evangelical writer of travel works and hymns, Josiah Conder, described his book as marred by ‘unaccountable inaccuracy’.4 Moreover, Forsyth’s experience explained why travel was risky: the Scot was apprehended on his way back to Britain and spent eleven years as a captive of the French. His fate highlighted the dangers of visiting the continent at a time of conflict.5

With the peace that followed Napoleon’s final defeat, thousands of British travellers began to visit Italy. The political map of the peninsula changed dramatically after the collapse of French rule. Napoleon had divided Italy into three political units: the Kingdom of Italy in the north east, with its capital in Milan, but also including Venice and Bologna; the Kingdom of Naples in the south; and a wide area – including Turin, Florence, and Rome – incorporated directly into metropolitan France. The peacemakers at the Congress of Vienna sought in large part to re-establish the status quo ante. The Bourbons returned from the safety of their court at Palermo to rule the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from Naples; the House of Savoy similarly left its Sardinian fastness and re-established the court in Turin, once again to govern mainland Piedmont, now swollen with the acquisition lands from the former Republic of Genoa. Pope Pius VII, back in Rome after being held as a virtual prisoner in France, reassumed authority in the Papal States. Francis I of Austria regained his former Lombard provinces. These he fused into a single Kingdom with the lands of the former Venetian Republic, which he had briefly ruled from 1798 to 1806. Meanwhile, Tuscany once again received a Habsburg Grand Duke, Ferdinand III, brother of Francis I of Austria. The Austrian Emperor’s daughter – Napoleon’s estranged wife, Marie Louise – became Duchess of Parma for life, while another Habsburg, Francesco IV d’Este, became Duke of Modena. The former Republic of Lucca became the fiefdom of the Parmense Bourbons until the death of Marie Louise permitted them to reclaim their former domains. This reorganisation of territory effectively re-established the eighteenth-century ancien régime frontiers, minus the former republics. British travellers, like the engineers of the Vienna settlement, also initially looked back to the eighteenth century, retracing the routes of the grand tourists. A significant minority soon chose to take up residence, benefitting from the cheapness of living and warmer climate. As urban historian Rosemary Sweet has pointed out, Henry Coxe, author of one of the most noted guides to Italy to appear in the immediate aftermath of the wars, prefaced his book ‘with fifty pages of advice, most of which consisted of instructions on how to live economically but genteely without giving the appearance of scrimping’.6 As the century progressed growing numbers of bourgeois and aristocratic Britons began to make the journey south to Italy’s patchwork of states as a cultural rite of passage.

Many of the British travellers who set out for Italy after 1815 were well-informed, at least about historic sites. But they generally arrived in the peninsula with strong and frequently skewed preconceptions, both about the culture and about the politics and society of Italy. One reason for the distorted assumptions of British travellers in the years immediately after the Congress of Vienna was that tourists were often reliant on guidebooks cobbled together in great haste by individuals who had limited knowledge of the country, and certainly no recent experience of it. For example, Henry Coxe’s Picture of Italy, published in 1815, was both highly derivative and full of information that was no longer accurate. As Coxe acknowledged in his introduction: ‘The author has not always trusted to his own personal observations, but has availed himself of every light which he could derive from men as well as books.’7 ‘Every light’ here often meant simply recycling almost verbatim large chunks of Eustace’s Classical Tour, or just translating the writings of the eminent French surgeon Philippe Petit-Radel (1749–1815).8 This practice explains why, for example, Coxe’s description of Venice contains a long (and very tedious) passage on the city’s medical practitioners, including a description of the best resident French physicians, all of whom had quit the city by the time of publication.9 In Hints to Travellers in Italy by the archaeologist and antiquarian Sir Richard Colt Hoare, also published in 1815, the author freely admitted that much of what he said would be out-of-date, based as it was on his own experiences of living in Italy before it had been despoiled by Napoleonic tyranny.10

There was nothing new about borrowing heavily from other writers. Indeed, the Galignani family – the anglicised Italian printers, who specialised in exploiting the lack of international copyright agreements to publish high-quality, cheap reprints from their base in Paris – made a virtue of plundering guides and travel accounts when in 1819 they published Galignani’s Traveller’s Guide through Italy, or a Comprehensive View of the Antiquities and Curiosities of that Classical and Interesting Country: Containing Sketches of Manners, Society, and Customs [...], carefully compiled from the works of Coxe, Eustace, Forsyth, Reichard and others.11 In addition, when British travellers arrived in Italy they often made use of older guides alongside recently published but often inaccurate newer ones. For example, the visitor to Rome might use J. Salmon’s two-volume An Historical Description of Ancient and Modern Rome (1800) or the work from almost forty years earlier on which Salmon himself was extremely dependent: Giuseppe Vasi’s Itinerario istruttivo diviso in otto stazioni o giornate per ritrovare con facilità tutte le antiche e moderne magnificenze di Roma (1763).12

Travel literature regarding Italy became much more varied during the years after 1815, and gradually came to offer potential visitors to the peninsula a more nuanced picture. But it was not until the publication of Murray’s Handbooks in the 1840s that reliable guides to the peninsula became available in English.13 Until that decade, those seeking to inform themselves often had recourse to a wide variety of texts, often written by native Italians, or Germanophone or Francophone travellers (whether in translation or not) alongside works by English travellers. For example, a traveller to Sicily – one of the few areas of Italy to which the British had maintained access throughout the Napoleonic Wars – might well prepare for a trip by reading, or consulting as a guide while actually on the island, books by a range of authors from the later eighteenth century: Patrick Brydone (1736–1818) and Henry Swinburne (1743–1803) in English, Jean-Claude Richard (Abbé) de Saint-Non (1727–1791) and Dominique Vivant Denon (1747–1825) in French, cicisbeo Leopold zu Stolberg (1750–1819) and Johann Hermann von Riedesel (1740–1784) in the original German or English translation, as well as texts from still earlier periods. Given the tendency of authors to borrow heavily from one another – whether they acknowledged or were even aware of what they were doing – British engagement with Italy was part of a truly transnational but frequently very conservative process.14

If preparation for a tour of Italy was ‘transnational’ in nature, then the principal reason for such a tour, at least ostensibly, was to visit historical and picturesque sites (see fig.1). The overwhelming bulk of travel and advice books emphasised classical remains, and, to a lesser extent, medieval, Renaissance, and some later art and architecture. At the same time travel was informed by a desire to engage with the Italy of a literary imagination, whether that was Horace, Tasso, Petrarch, Dante, or, as Byron suggested when reflecting on Venice in Canto IV of ‘Childe Harold’, the work of non-Italians who had written about the country. Byron playfully pointed to his engagement with Venice through the work of four writers – ‘Otway, Radcliffe, Schiller, Shakespeare’s art’ – not one of whom had set foot south of the Alps.

By the late 1810s British engagement with Italy had come to be shaped heavily by a handful of Romantic poets and writers. Even before the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Germaine de Staël – a bitter critic of the French Emperor – had won a huge British audience with her Corinne ou l’Italie, first published in French in 1807. Immediately attracting the attention of translators, fourteen English-language editions appeared within just three years.15 The novel was incredibly popular: Mary Shelley read the book three times between 1815 and 1818; Elizabeth Barrett Browning had read it three times by the age of twenty-six.16 It also came to function ‘as an unconventional tourist guide’,17 identified by Eustace as ‘the best guide or companion which a traveller can take with him.’18 In her novel, de Staël portrayed Italy as sunk into decadence but nevertheless retaining enormous cultural vitality, a place of talented, over-bearing women but effeminate and apolitical men, which gloried in the fine arts and possessed beautiful landscapes but lacked moral purpose or energy.19 For her ‘The Italians are more remarkable for what they have been, and might be, than for what they are’.20

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Hannibal Passing the Alps, for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 243 x 305 mm

Tate D27666

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Fig.2

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Hannibal Passing the Alps, for Rogers's 'Italy' c.1826–7

Tate D27666

From his self-imposed Italian exile, Byron soon buttressed Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage with other images of Italy and its inhabitants, which rapidly filtered into the British imagination. Sometimes Byron focused on more playful themes, emphasising sexual licence and the role of the cicisbeo (the publicly acknowledged male companion of a married woman) in Italian society.25 The most notable example of such an approach, outside Byron’s personal (but remarkably public) correspondence,26 was in his charming and extremely funny ‘Beppo’ (1817). This tale, the poet’s first experiment with ottava rima, was set in the decadent late Republic, the era of Casanova and Goldoni. Most of Byron’s other work on Italian themes carefully eschewed the (near) contemporary, and was generally grimly dramatic in its engagement with earlier periods of history, most notably in his Venetian plays, The Two Foscari and Marino Faliero. Byron became the touchstone by which British visitors measured Italy. Even those who were not entirely convinced, such as the writer Frances Trollope (1779–1863) – who perversely championed the superiority of Richard Monckton Milnes (1809–1885), even though she systematically misspelled his name as ‘Milne’ – felt the need to quote from and allude to the poet in their accounts of Italian travels.27

Many other romantics echoed the Gothic portrayal of Italy, famously articulated in Ann Radcliffe’s (née Ward) romance The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794).28 This in turn was heavily dependent in its descriptions of cities and landscapes on works such as the Observations and Reflections Made in the Course of a Journey through France, Italy, and Germany (1789) by Samuel Johnson’s friend Hester Lynch (Thrale) Piozzi (née Salusbury), and Travels through France and Italy (1766) by the Scottish author Tobias Smollett.29 The readiness to envisage Italy as a land of Gothic fantasy – made all the more lurid in English eyes because both Catholic and meridional – was manifest in the youthful work of Shelley, who was only seventeen and still studying at Eton when he wrote Zastrozzi: A Romance (1810). The plot of Zastrozzi unfolds between Bavaria and the Venetian terraferma. Shelley was totally ignorant of both. Shelley’s play The Cenci (1819) – a dramatic tale of incest and parricide – was written after he had taken up residence in Tuscany, but it similarly peddled the same historicised and Gothic vision of Italy. The use of past episodes of Italian history as a backdrop or source for exciting dramas was equally widespread among Walter Scott’s many Italian imitators, such as Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi and Massimo D’Azeglio, whose works were known, if not widely read, in the English-speaking world.30 This historical or historicised idea of Italy remained popular with anglophone writers. The consequence was that many British travellers reached the peninsula with their heads filled with ideas derived from such romances: the inspiration to visit Italy might be the classics or Dante, Michelangelo or Palladio, but it could also stem from old copies of Radcliffe plucked from parental shelves, or reprints of such classics, or perhaps the works of her later imitators, such as the swashbuckling novel The Bravo (1831) by the American novelist James Fenimore Cooper, which swiftly appeared in European editions, and was soon adapted as a successful stage play.31

If British travellers often arrived in Italy with their ideas shaped by drama, poetry and prose fiction, they also came to engage seriously with the country’s history. This was often the classical past, encountered through innumerable Roman and, for the south, Greek texts, as well as later accounts of the same, including Gibbon’s substantial The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–89).32 But a newer historiography dealing with the middle ages and more recent periods also began to appeal to a wider readership. One especially significant work was the vast study of medieval Italy by the Genevan economist and historian Simonde de Sismondi. The influence of Sismondi’s Histoire des Républiques Italiennes du Moyen Âge (1809–18) was twofold. Not only was the book widely read – or, probably more accurately, given its enormous length, widely sampled – but it also had a profound effect when mediated through or recycled by British writers.33 Byron made use of it as a source for his Faliero;34 it was translated into a popular, heavily-abridged, pocket-sized, single volume;35 Ruskin unreasonably bade Effie copy all the passages from the vast work that ‘to the remotest degree’ dealt with Venice.36 Sismondi’s book cast medieval Italy in a positive light in the centuries before the peninsula succumbed to decadence and defeat. The Histoire des Républiques emphasised that, despite their frequent internecine strife, the common political structures and practices of the Italian comuni represented a shared Italian political culture, which fostered a profound sense of liberty and independence. It is perhaps surprising that Sismondi’s prolix and often rather repetitive volumes had a huge influence on the way in which British historians wrote about Italy, but this influence cannot be denied. For example, the Whig historian Henry Hallam was heavily dependent on Sismondi for the Italian sections of his survey of medieval Europe, View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages (1818). Hallam’s book in turn remained the standard English language account of the middle ages for decades, widely read and also influential in shaping the content of guidebooks and histories, and providing background information for the writers of fiction.37

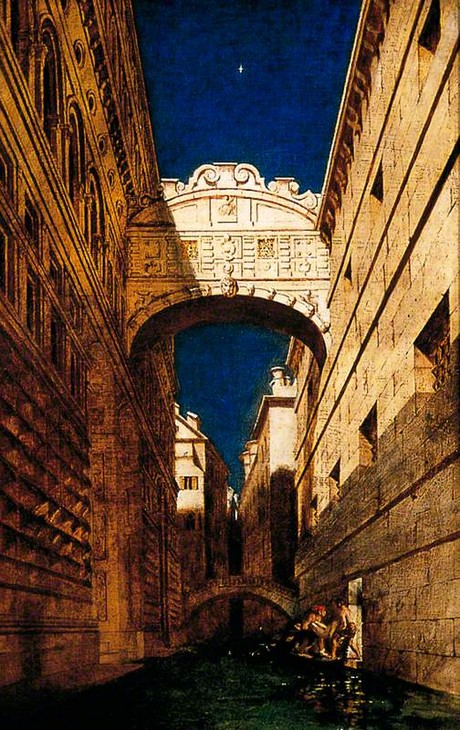

William Etty

Bridge of Sighs, Venice 1836

York Art Gallery

Fig.3

William Etty

Bridge of Sighs, Venice 1836

York Art Gallery

The influence of works by the likes of Daru and Sismondi highlights the degree to which British views of Italy – past and present – in the years between the Congress of Vienna and the revolutions that shook the peninsula in 1848 were the product of a dialogue, which was not only transnational, but shaped by the relationships between different creative arts and academic disciplines.42 A key role in this process of construction of British attitudes to Italy during Turner’s lifetime was the presence of Italian exiles, many of whom came to play a significant part in the cultural life of Restoration Britain. Many arrived because of their involvement in the failed 1820–1 revolutions in the southern Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and in Piedmont, or to escape reprisals following the widespread conspiracies and insurrections of the early 1830s.43 A smaller number had fled in the aftermath of Napoleon’s fall, many simply to escape from the sometimes stifling nature of Italy’s Restoration governments. One of the first major figures to arrive in England was the Greek-born Venetian and Italian patriot Ugo Foscolo, best known as the author of the epistolary novel Le ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis (1798–1802) and the poem ‘Dei Sepolcri’ (1807). Foscolo had been assiduously courted, if not trusted, by the Austrian authorities before his flight to England. From 1822 he lived in St John’s Wood, his luxurious cottage a magnet for Italian exiles and British literati alike. Foscolo became ‘the petted and spoilt Marmozet of the upper circles of London’,44 widely-admired and massively-disliked in equal measure.45 Foscolo was simply the most famous of many Italians whose presence in England helped shape attitudes to the peninsula. British journals and magazines not only published articles about the man and his literary production, but also employed him as an essayist and reviewer, thus allowing this atheist, democrat, and nationalist to receive a wide British audience, even though his views were extremely unrepresentative of those of most of his compatriots.46

Something similar would occur with another charismatic and talented exile, the patriot and conspirator Giuseppe Mazzini, who took Foscolo as a role model.47 Resident in London from 1837,48 Mazzini would prove ‘unique among early exiled democrats in his ability to disseminate his ideas on Italy across Britain’.49 Notwithstanding his skill at reaching very varied constituencies, and his close connections with leading British intellectuals and writers (the Carlyles, Browning, Macauley, Dickens, Mill), Mazzini only came to real prominence in 1844 because of the scandal over Sir James Graham’s order to intercept Mazzini’s mail at the request of the Austrian ambassador.50 A brooding and romantic figure, who had travelled less in his native Italy than the vast majority of British visitors to the country, Mazzini exercised a disproportionate influence over the image of Italy in the British imagination. For example, Mazzini inspired Robert Browning’s poem, ‘Italy in England’ (later called ‘The Italian in England’). This poem, probably composed in 1844, described the aftermath of a completely fictitious anti-Austrian insurrection in Venetia. While Venice would be at the centre of some of the fiercest revolutionary resistance in 1848, in 1844 Austrian Venetia had not only long been renowned for political passivity, but was quite possibly the single most quiescent region of Europe in the post-Vienna Settlement era.51

Sympathy for those Italians who wished to drive out the Austrians and to overturn the generally conservative post-1815 regimes grew steadily during the Restoration era. Indeed, at the fall of Napoleon most politically aware Britons had been indifferent to the fate of lands south of the Alps, and few Britons had challenged the new territorial and political order imposed at the Congress of Vienna. When, for example, Lord William Bentinck, who had been British commander in the Mediterranean and de facto governor of Sicily in the final years of the Napoleonic Wars, called in Parliament for the restoration of Genoese independence, his appeals fell on deaf ears.52 But British indulgence to Italian political exiles coupled with the influence of radical and liberal romantics, such as Shelley and Byron, contributed significantly to a growing British critique of the political situation in post-Napoleonic Italy. This was fed by the often ill-informed comments of British travellers who had an axe to grind. Byron, a Foxite Whig whose politics were always more to do with posturing and self-fashioning than any approximation to informed political observation, calumnied the Austrian authorities in Lombardy-Venetia (from whom he received considerable hospitality): his only significant example of Austrian ‘tyranny’ was about the difficulty of acquiring English newspapers (itself a lie).53 Shelley, a more thoughtful and less self-serving political observer, but equally parti pris in his politics, was similarly happy to throw around accusations about the oppressive Habsburg government and excessive taxation in both his correspondence and his poetry.54

Romantic poets were not the only Britons to attack the new order in Italy, even while the British government upheld Metternichian Austria as a force for stability. Some of the commentators were simply shrill. A good example of this is the work of Catherine H. Govion Boglio Solari, an Englishwoman married to an Italian aristocrat who wrote under the nom de plume of ‘A Lady of Rank’. Railing against both the French and the Austrians, she complained furiously of those who ignored the plight of ‘the forlorn sisterhood of Italian states’.55 A more measured and effective critic of the new status quo was Lady Morgan (1781–1859), whose Italy – written, as the author frankly admitted, to make money – was innovative both in its readiness to view the current state of the peninsula, and in the remarkably fresh approach which it took to its subject matter, even while acknowledging the debt to other authors. Morgan, an Irish novelist who more than wearing her patriotic and liberal opinions upon her sleeve brandished them like a standard in battle, wrote her two volume book based on her travels with the conscious intention of being political.56 Thus, for example, she was forthright in her condemnation of the British betrayal of the Genoese ‘to their ancient foe, their inveterate rival, and long-detested neighbour – the King of Sardinia’,57 contemptuous of Maria Luisa of Parma’s charity to the church but failure to reform her prisons,58 dismissive of Murat’s inability to control his generals’ rapacious requisitioning,59 and systematically hostile to the ‘false and cruel paternal policy’ of the government of Naples, which, ‘always purely and frankly despotic’, had ‘assumed the character of eastern tyranny’.60 Nor was she scared to make predictions of future developments, arguing for example, that ‘When the epoch of Italian deliverance shall arrive, the central position of this city [Bologna], and the awakened character of its inhabitants, will render it the nucleus of public opinion, and will give to it a decided influence upon the destinies of the Peninsula’.61

Morgan was scholarly and well informed, capable of making judicious and generally less hackneyed assessments of art and architecture than her peers; her lively and often funny prose was rich in detail. She was often prejudiced, but she backed up her position by appeal to contemporary detail, and ranged widely over issues as varied as the impact of tariffs on the economy to the treatment of religious orders, from the quality of libraries and universities to the nature of censorship, from agricultural practices to the quality of musical performances. Hers was a richly informative book. It outshone even the thoughtful commentary of the translator of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, William Stewart Rose (1775–1843) in his Letters addressed to the historian Henry Hallam.62 Morgan’s Italy also had a capacity to convey local colour that no other Anglophone author matched until Charles Dickens published Pictures from Italy in the 1840s.63 As J.H. Whitfield remarked, what set Morgan apart from most of her peers was her ability to capture ‘the living, moving, breathing Italy’.64

If Morgan’s Italy was exceptional in its boldness of opinion and engagement with recent history and modern politics, it is striking that those accounts of travel that dealt most effectively with contemporary Italian mores were more often than not the work of female authors. Women travel writers who described Italy during the Restoration era built on a tradition already established in the eighteenth century by such figures as Lady Anna Miller (née Riggs; 1741–1781),65 Hester Thrale Piozzi (1741–1821), and Mariana Starke (1761–1838), whose travel writings bridged the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras.66 But it is also clear, when looking at the writing about Italy from the years between 1815 and 1848, that British women were frequently more interested and astute observers than their male companions. Whether it was Fanny Trollope’s attempts to replicate the success of her Domestic Manners of the Americans,67 the Irish-born novelist Countess Marguerite Gardiner of Blessington (née Margaret Power; 1789–1849) in her Idler,68 the governess Anna Jameson (née Murphy; 1794–1860) in her lightly fictionalised Diary of an Ennuyée,69 or the writing of Charlotte Anne Eaton (née Waldie; 1788–1859), best known for her account of Waterloo,70 the accounts given by women were less likely to focus simply on displaying a scholarly knowledge of the classics or medieval history, or to indulge in set-piece rhetorical attacks on the political status quo or the Catholic Church. Thus Eaton’s study of Rome is full of fascinating detail, a virtual ethnography of the papal city, in which the reader learns of the locals’ reluctance to sing, of the blessings of horses on St Anthony’s day, of superstition and trials for witchcraft. Jameson’s book is similarly informative on a huge array of topics ranging from the reasons behind the decline of Venetian trade, conditions of the peasantry in different regions, the negative impact of Austrian censorship, modes of agricultural production, fireflies, and, of course, Italy’s artistic heritage, even if she felt the need – like Blessington and Trollope – to refer repeatedly to Byron to give her work authority.

It is instructive to compare what Shelley’s widow had to say about Italy with Byron’s poetry and letters. Dickens’s friend, the Daily Telegraph journalist George Augustus Sala wrote many years later:

Byron gushes tremendously in Childe Harold ... In his letters, however, to Murray, and in his conversations with his friends, Byron showed that he had a very shrewd, practical, and even humorous appreciation of Italy as a land inhabited, not by poetical abstractions, but by substantial human beings; and there can be little doubt that, had Lord Byron chosen to do so, he might have written one of the best prose works on Italy or the Italians which it was possible to endow his country’s literature.71

Sala is unfair on Byron’s poetry, but it is true that it tells the reader little about Italy, with which it engages principally through referencing great literature. But Sala is also gravely mistaken about Byron’s letters. Although Byron resided in Italy from 1816 to 1823, his correspondence tells the reader almost nothing about the country. Instead it is concerned overwhelmingly with the poet’s favourite topic: himself. The letters tell us about his sexual conquests, his writing, his dogs and other animals, about his financial worries, about his involvement in Italian politics. But it is almost impossible to learn anything about Italy from Byron’s pen. Indeed, perhaps the British obsession with Byron as a key to understanding Italy lay precisely in the way in which he seemed to create a template for visiting the country and enjoying it, without really ever getting to know it.

Admittedly, Mary Shelley’s early letters often focused on personal relationships, and generally displayed a marked antipathy towards Italians. In one letter to her friend Maria Gisborne (née James, later Reveley; 1770–1836), a resident of Livorno, she even expressed a universal Anglo-Saxon loathing for the peninsula. Advising Gisborne that she should move to Marlow, Shelley continued ‘I am sure that you would be much happier than in Italy. How all the English dislike it’.72 Yet by the time Mary Shelley was in her early forties, she had become a much more sympathetic and sensitive observer of the Italian political situation and the needs and aspirations of its population. In her Rambles in Italy and Germany, she lambasted the anti-Italian sentiments of other travel writers, suggesting that the durability of such negative views reflected not reality but ignorance and indolence on the part of the authors.73 Deeply aware of the risks of succumbing to clichés, she also warned that ‘When we visit Italy, we become what the Italians were censured for being – enjoyers of the beauty of nature, the elegance of art, the delights of climate, the recollections of the past, and the pleasures of society, without a thought beyond’.74 It was this awareness of the pitfalls of writing about Italy that permitted Mary Shelley to engage with the modern Italians. Echoing Sismondi, she saw the shortcomings of Italians as a product of bad government, their vices the product of misrule and ‘a misguiding religion’.75 Shelley’s Rambles demonstrated an astute judgement of the international situation, which so determined the nature of Italian political life; the book applauded the ‘new aspect’ of the country that ‘was struggling with its fetters’,76 and argued that if Italy wished to achieve freedom and independence its population needed first to ‘learn to practise the severer virtues; their youth must be brought up in more hardy and manly habits; they must tread to earth the vices that cling to them as the ivy around their ruins’.77 Yet she also bewailed the absolute inability of Italians from any part of the peninsula to construct a decent flower garden.78 There is no doubt that Mary Shelley viewed the Italians with the same sense of patronising superiority that characterised the bulk of British travellers (especially the vast majority whose prejudices were reinforced by anti-Catholic sentiment), but her account, like Lady Morgan’s, was an attempt to do more than show her own learning and her virtuoso skills as a wordsmith, or to mock Italian decadence and superstition. It is an engaging, sometimes passionate, opinionated, and very personal account.

British women’s descriptions of Italy were more inclined to engage sensitively with contemporary Italy than those of their male compatriots. But, regardless of gender, most authors were not only critical of the supposedly oppressive nature of Italian governments, but also of their failure to accommodate the expectations of foreign visitors. Almost all accounts of Restoration Italy at some point mention the annoyance of dealing with the police or border guards or the absurdities of over-vigilant censorship. Rose, for instance, wrote with irritation of the obstructive nature in which he was refused entry to Habsburg Lombardy in the summer of 1817 because he had failed to get either the Austrian Minister in London or a Habsburg diplomatic agent in Genoa to sign his passport.79 Although Murray’s Handbook of 1842 advised that ‘travellers have only themselves to blame, if they omit to furnish themselves with the needful credentials which are obtained without the slightest difficulty’, annoyance with officious, inefficient, or corrupt frontier guards became something of a set-piece in British travel writing about Italy, and perhaps contributed to the growing antagonism towards the Restoration order.80 Another common theme was to stress the diversity of Italy, whether in terms of artistic style or social conventions, of topography or language. Thus, the Italian-educated, reactionary, former officer from the British army, André Vieusseux, wrote in 1821:

I think the Italians are but imperfectly known, and often unjustly abused, and are generally included by foreigners in one common description of character, while, in fact, the inhabitants of the various states of that much divided country, form so many distinct nations. A Tuscan and a Neapolitan, a Lombard and a Genoese, a Venetian and a Roman, are as different from one another, as the Germans are from the English, or the Dutch from the French.81

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner

A Cricket Match in Rome Between Eton and the Rest of the World in the Gardens of the Villa Doria Pamphili 1850

Private collection

Fig.4

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner

A Cricket Match in Rome Between Eton and the Rest of the World in the Gardens of the Villa Doria Pamphili 1850

Private collection

Notes

For example, few Britons visited the former Venetian mainland provinces in the period 1798 to 1805, despite their being part of the Austrian Empire. On the fate of the few British residents in Venetia during the first Austrian domination of the region, see David Laven, ‘The Fall of Venice: Witnessed, Imagined, Narrated’, Acta Histriae, vol.19, no.3, 2011, pp.341–58.

The British did maintain a presence in Sardinia and, especially, Sicily, neither of which ever fell under French control because of protection by the Royal Navy.

John Chetwode Eustace, A Tour through Italy, exhibiting a view of its scenery, its antiquities, and its monuments; particularly as they are objects of classical interest with an account of the present state of its cities and towns and occasional observations on the recent spoilations of the French, 2 vols., London 1813; Joseph Forsyth, Remarks on Antiquities, Arts, and Letters during an Excursion in Italy, in the Years 1802 and 1803, London 1813. Both works were reprinted regularly over the next two decades. It is known that Turner certainly consulted Eustace on his Italian travels on account of the notes he made. See, for example, Nicola Moorby, ‘Notes by Turner from Eustace’s ‘A Classical Tour Through Italy’ c.1819 by J.M.W. Turner’, catalogue entry, July 2008, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/joseph-mallord-william-turner-notes-by-turner-from-eustaces-a-classical-tour-through-italy-r1138764 , accessed 22 September 2015.

See Keith Crook, ‘Joseph Forsyth and French Occupied Italy’, Forum for Modern Language Studies, vol.39, no.2, 2003, pp.136–51.

Henry Coxe, Picture of Italy; being a guide to the antiquities and curiosities of that classical and interesting country: containing sketches of manners, society and customs to which are prefixed dialogues in English, French & Italian, London 1815, p.vi. Coxe’s real name was John Millard.

Philippe Petit-Radel, Voyage historique, chorographique et philosophique dans les principales villes de l’Italie en 1811 et 1812, 3 vols., Paris 1815.

On the Galignani family’s publishing practices, see: Giles Barber, ‘Galignani's and the Publication of English Books in France from 1800 to 1852’, The Library, series 5, vol.16, no.4, 1961, pp.267–86; James J. Barnes, ‘Galignani and the publication of English Books in France: a postscript’, The Library, series 5, vol.25, no.4, 1970, pp.294–313; William St Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period, Cambridge 2004, pp.293–9.

The first to appear was Handbook for travellers in Northern Italy, London 1842, compiled by the eminent mediævalist, Sir Francis Palgrave. To a degree the Handbook built on earlier guides as such as the laconic if reasonably comprehensive guide by the prolific travel writer Mariana Starke, Travels in Europe between the years 1824 and 1828 adapted to the use of travelers, London 1828.

The major English language works on Sicily was Patrick Brydone, A tour through Sicily and Malta in a series of Letters to William Beckford, Esq. of Somerly in Suffolk, 2 vols., London 1772, and Henry Swinburne, Travels in the Two Sicilies in the years 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780, 2 vols., London 1783–5. A French edition of Swinburne soon appeared, translated by the precocious and brilliant Louise-Félicité Guynement de Kéralio, Voyage dans les Deux Siciles en 1777, 1778, 1779 et 1780, 2 vols., Paris 1785; a second translation followed, this time by Benjamin de Laborde, Voyage de Henri Swinburne dans les Deux Siciles, en 1777, 1778, 1779 et 1780, 5 vols., Paris 1785–7, which included notes and extracts from Denon’s Voyage (see below); the German edition was translated by Johann Reinhold Forster, Hamburg 1785. Key French texts on Sicily, which were widely available in Britain, included: Jean-Claude Richard de Saint-Non, Voyage pittoresque ou description des royaumes de Naples et de Sicile, 5 vols., Paris 1781–6; Dominique Vivant Denon, Voyage en Sicile, Paris 1788; Jean-Pierre Houël, Voyage pittoresque des Isles de Sicile, de Malte et de Lipari, où l’on traite des antiquités qui s’y trouvent encore; des principaux phénomènes que la nature y offre; du costume des habitans, & de quelques usages, 4 vols., Paris 1782–7. Among German works consulted by British travellers were: Johann Heinrich von Bartels, Briefe über Kalabrien und Sizilien, 2 vols., Göttingen 1789; Friederich Leopold, Graf zu Stolberg, Reisen in Deutschland, der Schweiz, Italien und Sizilien in den Jahren 1791 un 1792, 4 vols., Königsberg and Leipzig 1794, translated as Frederic Leopold Count Stolberg, Travels through Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Sicily, 2 vols., London 1796; Johann Hermann von Riedesel, Reise durch Sicilien und Großgreichenland, Zurich 1771; Graf Michal von Borch, Briefe über Sicilien und Malthe, Bern 1783. Earlier books about the island included: Tomaso Fazello, Le due deche dell’Historia di Sicilia, trans. by Remigio Nannini, Venice 1574 (Münter gives the date as 1573); Jacques-Philippe d’Orville (Jacobi Philippi d’Orville), Sicula, 2 vols., Amsterdam 1764; Giuseppe Maria Pancrazi, Antichità siciliane, 2 vols., Naples 1751–2. More recent English accounts were: William Wilkins, The antiquities of Magna Græcia, Cambridge 1807; Francis Collins, Voyages to Portugal, Spain, Sicily, Malta, Asia-Minor, Egypt, &c, &c from 1796 to 1801 with historical sketches and occasional reflections, both moral and religious, self-published 1807 and 1813; John Galt, Voyages and travels in the years 1809, 1810, and 1811 containing statistical, commercial, and miscellaneous observations on Gibraltar, Sardinia, Sicily, Malta, Serigo, and Turkey, London 1812.

Madame (Anne-Louise-Germaine) de Staël Holstein, Corinna or Italy, 3 vols., London 1807; another translation appeared in the same year by Dennis Lawler, 5 vols., London 1807. Isabel Hill’s translation, which became the standard English version of the text, was first published in 1833. Madame de Staël, Corinne, London 1833. Numerous later editions testify to the continued popularity of the work.

Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850, London 1987, p.161; Maureen McCue, British Romanticism and the Reception of Italian Old Master Art, 1793–1840, Farnham 2014, p.43. Angelica Goodden, Madame de Staël: The Dangerous Exile, Oxford 2008, p.175.

Eustace, ‘Preliminary discourse’, Classical Tour, 6th edn, Paris 1837, vol.1, p.8. William Thomas Lowndes cited Eustace in his sole comment on Corinne, besides the fact that De Staël’s novel had been ‘frequently reprinted’. The Bibliographer’s Manual of English Literature, London 1834, vol.4, p.1727.

On British responses to de Staël, see Robert Casillo, The Empire of Stereotypes: Germaine de Staël and the Idea of Italy, Basingstoke 2006.

The translation is that of Isabel Hill, de Staël, Corinne (1833), p.16. The original French reads: ‘Les italiens sont bien plus remarquables par ce qu’ils ont été, et par ce qu’ils pourroient être, que par ce qu’ils sont maintenant.’

Italy. A poem. Part the first, London 1822, p.62. The first edition did not carry Rogers’s name. The second part was published to little acclaim in 1828.

Samuel Rogers, Italy a poem. With illustrations after J.M.W. Turner and T. Stothard, London 1830. The 1838 edition is usually considered the definitive version because of the higher quality of the plates. McCue, British Romanticism, p.128.

‘My Venice, like Turner’s, has been chiefly created for us by Byron.’ John Ruskin, Praeterita: The Autobiography of John Ruskin, Oxford 1978, p.268. Praeterita was first published in twenty-eight separate sections between 1885 and 1889. The OUP edition is a version of the 1899, three-volume edition.

The Italian institution of the cicisbeo or cavaliere servente was widely ridiculed across northern Europe, and seen as the embodiment of Italian decadence. Roberto Bizzocchi, Cicisbei: morale privata e identità nazionale in Italia, Rome and Bari 2008. For the English translation: A Lady’s Man: The Cicisbei, Private Morals and National Identity in Italy, Basingstoke 2014.

Much of Byron’s personal correspondence was made public after the poet’s death through Thomas Moore, Life of Lord Byron, London 1830. In addition, many of Byron’s letters from Italy were read out to a wider audience of friends. ‘His [Byron’s] tendency to treat correspondence as performance was now boosted by Byron’s consciousness that Murray would be reading out his letters proprietorially to the gathering of literary cronies beneath Thomas Phillips’ portrait of Byron in the Albemarle Street drawing room.’ Fiona MacCarthy, Byron: Life and Legend, London 2002, p.323.

British readers of journals were well-aware of the Italian interest in historical novels as a genre. Even though most works did not find their way into English translation, they were regularly reviewed. Thus, for example, novels by Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi – La battaglia di Benevento, L’assedio di Firenze, Isabella Orsini, duchessa di Bracciano – or Massimo D’Azeglio’s Ettore Fieramosca, o la Disfida di Barletta may not have found a large readership in Britain, but were certainly known to the reading public. See, for example, reviews of La battaglia di Benevento, Isabella Orsini, and Ettore Fieramosca respectively in ‘Article XIV’, The Foreign Quarterly Review, vol.4, no.7, April 1829, pp.321–3 and ‘Journal of Italian literature’, The Critic, vol.2, no.38, 20 September 1845, pp.418–20 and ‘Ettore Fieramosca; o, La Disfida di Barletta: racconto, di Massimo D'Azeglio, (‘Ettore Fieramosca; or, The Challenge of Barletta: a tale, by Massimo D'Azeglio’), The Athenæum, no.302, 1833, pp.525–6.

The Bravo, Paris 1831; J.B. Buckstone, Jacopo, the bravo: a story of Venice. A drama in three acts, London n.d., first produced at the Adelphi Theatre, 11 February 1833. This adaptation echoed that of the popular Covent Garden play Rugantino (1807) based on Matthew Gregory ‘Monk’ Lewis, The Bravo of Venice, London 1805, itself a loose translation of Heinrich Zschokke’s Abällino der grosse Bandit. Heinrich Zschokke, Abällino der grosse Bandit, Leipzig and Frankfurt 1795. On these transformations and on the works of Shelley and Radcliffe see Kenneth Churchill, Italy and English Literature 1764–1930, Basingstoke 1980, pp.21–45.

Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi, Histoire des Républiques Italiennes du Moyen Âge, 16 vols., Paris 1809–18.

Byron, remarking on the sources for his play in a letter to his publisher Murray, dated Ravenna, 17 July 1820, wrote: ‘History is closely followed. [...] I have consulted Sanuto – Sandi – Navagero – & an anonymous siege of Zara – besides the histories of Laugier Daru – Sismondi &c.’, Byron to Murray, Ravenna, 17 July 1820. Leslie A. Marchand (ed.), ‘Between two worlds’: Byron’s Letters and Journals, vol.7, 1820, London 1977, pp.131–2.

C.J.L. De Sismondi, A History of the Italian Republics. Being a view of the origin, progress, and fall of Italian freedom, London 1832.

Henry Hallam, View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages, 2 vols., London 1818. Hallam remarked that ‘The publication of M. Sismondi’s Histoire des Républiques Italiennes has thrown a blaze of light around the most interesting of European countries [...] during the middle ages. I am happy to bear witness [...] to the learning an diligence of this writer. [...] I cannot express my opinion of M. Sismondi in this respect more strongly than by saying that his work has almost superseded the annals of Muratori [the great eighteenth-century historian of Italy’s middle ages].’ From the note at the opening of Chapter III. Much more critical of Sismondi because of his chronological scope, prolixity, and interpretation, was George Perceval, who sniped at Hallam’s over-dependence on the Genevan. George Perceval, The History of Italy from the Fall of the Western Empire to the Commencement of the Wars of the French Revolution, 2 vols., London 1825, vol.1, pp.viii–x. On the relationship between nineteenth-century histories of Italy and the use of historical episodes in fiction, see C.P. Brand, Italy and the English Romantics: the Italianate Fashion in Early Nineteenth-Century England, Cambridge 1957, pp.187–9.

Pierre Antoine Noël Bruno Daru, Histoire de la Répblique de Venise, 8 vols., Paris 1819. Daru was also widely praised: Perceval lauded his conscientious use of primary sources, and ‘the judgment and ability with which he has used his resources’. Perceval, Italy, vol.1, p.64.

Claudio Povolo, ‘The creation of Venetian historiography’, in John Martin and Dennis Romano (eds.), Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilisation of an Italian City-state, 1297–1797, Baltimore 2000, pp.491–519, 492–9.

Some indication of the British awareness of contemporary Italian historiography can be derived simply from the way in which works of Italian history were reviewed in British journals. For example, in October 1837 one well-known publication reviewed a range of histories of Genoa, Florence, Naples, and more general works on Italy’s past, distant and recent. ‘Art. VI’, London and Westminster Review, vol.6, no.1, 1837, pp.132–68.

On the significance of exile see especially the work of Maurizio Isabella, most especially Risorgimento in Exile: Italian Émigrés and the Liberal International in the Post-Napoleonic Era, Oxford 2009. See also Donatella Abbate Badin, ‘Lady Morgan, an ambassador of goodwill to Italian exiles’, in Barbara Schaff (ed.), Exiles, Emigrés and Intermediaries: Anglo-Italian Cultural Transactions, Amsterdam 2010, pp.87–116, 87–90.

Walter Scott recorded on 14 November 1825: ‘Ugly as a baboon, and intolerably conceited, he spluttered, blustered, and disputed, without even knowing the principles upon which men of sense render a reason, and screamed all the while like a pig when they cut his throat.’ Eric Reginald Vincent, Ugo Foscolo: An Italian in Regency England, Cambridge 1953, p.22.

Foscolo published articles in a wide range of reviews, on topics that were largely linguistic, literary, or historical, and rarely overtly political. Articles and essays appeared in journals including: The Edinburgh Review, The Quarterly Review, New Monthly Magazine, European Review, Retrospective Review, London Magazine, and The Westminster Review. For a full list of Foscolo’s publications during his ten year residence in England, see ‘Appendix III’ in Vincent, Foscolo, pp.218–9. On Foscolo’s ability to reach an English audience with his lectures on Italian literature, see Glauco Cambon, Ugo Foscolo: Poet of Exile, Princeton 1980, p.305. More generally on Foscolo in England, see John Lindon, Studi sul Foscolo inglese, Pisa 1987. Despite being dated, Margaret C.W. Wicks, The Italian Exiles in London, 1816–1848, Manchester 1937, remains a judicious assessment of the rôle of Italians in England.

Marcella Pellegrino Sutcliffe, Victorian Radicals and Risorgimento Democrats: A Long Connection, Woodbridge 2014, p.4.

Maurizio Masetti, ‘The 1844 Post Office Scandal and its Impact on English Public Opinion’ in Barbara Schaff (ed.), Exiles, Emigrés and Intermediaries: Anglo-Italian Cultural Transactions, Amsterdam 2010, pp.203–214; F.B. Smith, ‘British Post Office Espionage, 1844’, Historical Studies, vol.14, no.54, 1970, pp.189–203.

On ‘Italy in England’ see John Woolford, Daniel Karlin, Joseph Phelan (eds.), Robert Browning: Selected Poems, Abingdon 2010, p.245. What is often overlooked is that the account of events in Browning’s poem cannot refer to any actual insurrection: the poem is set on the mainland of Venetia near Padua, and no risings took place on the Venetian terraferma between 1815 and 1847. Browning – inspired by the Bandiera brothers and by Mazzini – simply fantasises in the poem about the sort of anti-Austrian revolt of which Mazzini dreamed. On Venetian political quiescence, see David Laven, Venice and Venetia under the Habsburgs 1815–1835, Oxford 2002.

David Laven, ‘Punti di vista britannici sulla questione veneziana 1814–1849’, in A. Lazzaretto Zanolo (ed.), La «primavera liberale» nella terraferma veneta 1848–1849, Venice 2000, pp.35–49, 35.

On Byron’s wilful misrepresentation of the political situation in Italy, see David Laven, ‘Lord Byron, Count Daru, and anglophone myths of Venice in the nineteenth century’, MDCCC ‘Ottocento, vol.1, no.1, 2012, pp.5–32, 7–9. More generally see Malcolm Miles Kelsall, Byron’s Politics, Brighton 1987.

Frederick L. Jones (ed.), The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 vols., Oxford 1964, vol.2, p.41. See also Shelley’s ‘Lines written among the Euganean Hills’ (1818).

Venice under the yoke of France and of Austria with memoirs of the courts, governments, and people of Italy, London 1824, vol.1, p.2.

Donatella Abbate Badin, Lady Morgan’s Italy: Anglo-Irish Sensibilities and Italian Realities, Bethesda, MD 2007. The book was commissioned by her publisher. Lady Morgan (née Sydney Owenson), Italy, 2 vols., London 1821. Colburn almost immediately published a three-volume edition of the same work. Before 1821 was out, Italy had also been published in three volumes by A. & W. Galignani in Paris.

J.H. Whitfield, ‘Mr Eustace and Lady Morgan’, in Charles Peter Brand, Kenelm Foster, and Uberto Limentani (eds.), Italian Studies presented to E.R. Vincent, Cambridge 1962, pp.166–89, 182.

Lady Anna Miller, Letters from Italy describing describing the manners, customs, antiquities, paintings, &c. of that country, in the years MDCCLXX and MDCCLXXI, to a friend residing in France. By an English woman, 3 vols., Dublin 1776. The work was published by Edward and Charles Dilly as late as 1827.

Mariana Starke, Letters from Italy, between the years 1792 and 1798 containing a view of the Revolutions in that country, 2 vols., London 1800; Travels in Italy between the years 1792 and 1798 containing a view of the late revolutions in that country, London 1802. G. & S. Robinson published another edition of the Letters in 1815, cashing in on the renewed interest in travel to Italy. During the 1820s and 1830s, Phillips, John Murray, and the Galignani in Paris would release several new and expanded editions of this work.

Mrs Julian Marshall (Florence Ashton Marshall), The Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, 2 vols., London 1889, vol.1, p.225.

‘Time was when travels in Italy were filled with contemptuous censures of the effeminacy of the Italians – diatribes against the vice and cowardice of the nobles – sneers at the courtly verses of the poets ... and of late years travellers ... parrot the same, not because these things still exist, but because they know no better.’ Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Rambles in Italy and Germany in 1840, 1842, and 1843, 2 vols., London 1844, vol.1, pp.ix–x. Shelley excluded Lady Morgan from her general criticism.

Ibid., vol.1, p.97. See also p.87: ‘Their habits, fostered by their governments, alone are degraded and degrading; alter these, and the country of Dante and Michael Angelo and Raphael still exists.’

Ibid., p.x. Later she asserted: ‘ [...] the present governments of Italy know that there is a spirit abroad in the country, which forces every Italian that thinks and feels, to hate them and rebel in his heart.’ Ibid., p.123.

David Laven is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Nottingham.

How to cite

David Laven, ‘The British Idea of Italy in the Age of Turner’, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, September 2015, https://www