Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context

Sarah Victoria Turner

Carving was central to Moore’s practice as a sculptor throughout his career. In this essay Sarah Turner examines Moore’s carving through a close engagement with particular works that were carved from a range of materials. She also explores the ways in which carving became an evocative concept for sculptors, writers and critics in the twentieth century.

Throughout his career Henry Moore made carvings from stone, wood, plaster and polystyrene, and he also frequently wrote and commented on this method of making sculpture in his private notes and in numerous published outlets. Critics and art historians, both in his lifetime and after, have focused intensively on this aspect of Moore’s work – perhaps, some have argued, to the detriment of other sculptural processes and methods that he employed.1 Nevertheless, carving was unquestionably central to Moore’s practice and identity as a sculptor: between 1920 and 1940 nine in every ten of his sculptures, it has been claimed, were carved.2 This production attests to Moore’s dedication to the technique of carving, but why carving mattered so much to him – physically, materially andconceptually – is a topic that merits revisiting in some detail.

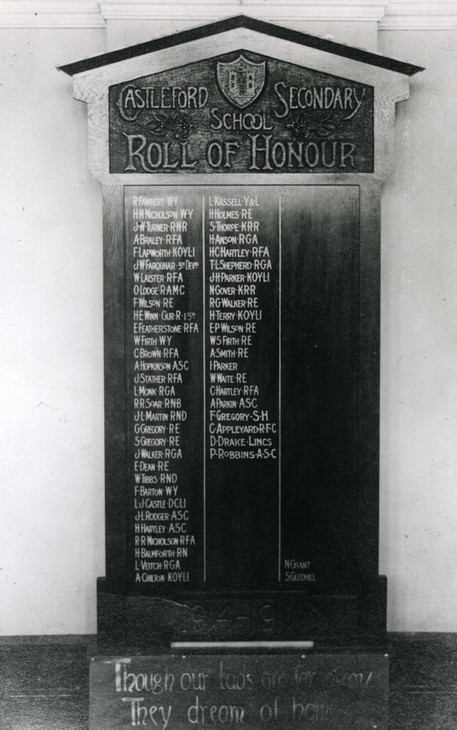

Henry Moore

Roll of Honour c.1916

Castleford High School, on loan to Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Roll of Honour c.1916

Castleford High School, on loan to Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Carving as sculptural practice has a deep, ancient, global history and this connection between a vision for modern sculpture and methods of making and manufacture that had been employed for centuries, millennia even, across the globe appealed deeply to Moore. Art historians have written about Moore’s fascination with the carved sculpture he encountered in the British Museum and illustrated publications as a student (and to which he would return constantly) from Nigeria, Sierra Leone, the Easter Islands, Haiti and many other places far away from his homes and studios in Yorkshire, London, Kent or Hertfordshire, places that he would only vicariously visit through the modern media of the photographic image.5 Learning the lessons of other sculptural traditions, whether they were close at hand, or far from home, was crucial to the development of Moore’s lexicon for sculpture. Eager to fix this connection between his turn to carving and his interest in what he termed ‘primitive sculpture’ (a phrase frequently used at the time to cover a geographically and chronologically vast range of work made outside of Europe), Moore often repeated in interviews that it was these encounters with the global traditions of sculpture that made him more sympathetic to carving over modelling because, he argued, ‘most primitive sculpture is carved’.6 Carving, however, was both local and global for Moore; it was important to the development of his identity as a quintessentially ‘English’ sculptor connected to the local landscape using native stone of the British Isles, and as an artist who associated with a world tradition of manufacture and making by taking a hard piece of material and working away at it to reveal new shapes and forms. Carving, as we shall see, was crucial to the establishment of his reputation, both nationally and internationally.

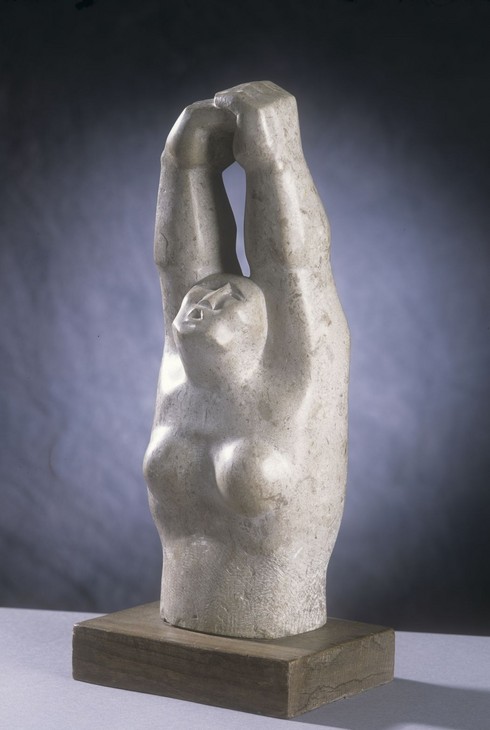

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

Manchester City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

Manchester City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

There is a chronology for Moore’s carved works, by which I mean one can trace different concerns, interests and influences on his practice as a carver at different moments in his career. For example, the primitivism of his carvings of the 1920s feel and look different to, say, the more abstract works of the 1930s and 1940s, or the larger Elmwood reclining figures of the 1950s and 1960s. But carving was also something of a constant, as a pursuit and idea that Moore returned to again and again throughout his life. He refined it, approached it differently and in different materials, and articulated what carving meant to him and his practice differently at times, but carving was always there. If it has been the early works in English stone such as Mother and Child (fig.2) that have received critical attention in relation to Moore’s practice as a ‘direct carver’, the carved work of his mid and late career are nonetheless worthy of serious of attention, not only in exploring how Moore’s approached carving throughout his career but also in charting the persistence of the idea (or concept) of carving from the time of his first carved works as a student through to his later pieces executed when he was one of the most well known and successful artists of the twentieth century. This essay, however, is not intended to be a chronological survey of his carvings, nor a summary of the voluminous pieces of writing about by Moore, or on Moore, and direct carving. Instead, it offers a critical discussion of the centrality of the practice of ‘direct carving’ which, hopefully, neither overplays or romanticises this aspect of his sculptural practice, nor underplays its significance, and even radicalism, for Moore. It makes the claim that we need look at direct carving across the span of his career rather than privileging just the early works and statements about this aspect of his working process, and that we also should view carving within a complex network of other techniques, aesthetic ideas and artistic contexts – as one of many modi operandi rather than in isolation as something which has, at times, accrued an almost cultish association and mystique.

Moore himself certainly helped cultivate such a prominent and hallowed place for this part of his sculptural practice. ‘To me, carving direct,’ he observed in a publication in 1986, ‘became a religion.’7 It was something to be believed in.8 Without a doubt, Moore became for many the high priest of the religion of ‘direct carving’ in early twentieth-century Britain but carving needs to be put back into dialogue with the other methods of manufacture and artistic practice that Moore used in his studios to make and think about sculpture.

Beginning, directly

What is ‘direct carving’? And is it different to simply ‘carving’ per se? The simple answer is no. All methods of carving require a direct action of removing material, often with specialist tools such as chisels, claws and mallets, to shape and form a three-dimensional object, whether for aesthetic or practical purposes. But the term ‘direct carving’ came to represent something distinctive and special, especially in the 1920s when Moore was making his name as a sculptor who privileged such a method. Direct carving has become a somewhat inflexible and fraught term in relation not only to Moore’s practice but also to twentieth-century sculpture more broadly. The place of direct carving in the historiography of sculpture in twentieth-century Britain has been discussed extensively elsewhere and I do not wish to repeat what has been so thoughtfully teased out by others. However, it is important to give the tenor of the debate to help articulate why ‘direct carving’ has become such a complicated and sometimes contentious term.

The practice of carving became central to the discussion of modern sculpture in the early twentieth century, first with a generation of artists older than Moore who worked directly into the material, namely the triumvirate of sculptors Eric Gill, Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, who all began work in period before the First World War. Direct carving was then taken up by Moore and his contemporaries, such as Barbara Hepworth, Gertrude Hermes, Frank Dobson and Eric Kennington, not only as a technique and method but also as a kind of doctrine that emphasised a ‘direct’ encounter with the material without the need for intermediaries such as skilled artisans to carry out the physical labour of the carving or equipment such as a pointing machine to translate an idea for a piece of sculpture from a (often modelled) smaller maquette into a larger piece of work in a material such as marble (fig.3). Curator Penelope Curtis has argued that Moore’s dominance within the histories of British sculpture has meant that ‘his history emphasises early twentieth-century-carvers at the cost of modellers’. Even more forceful is Curtis’s assertion that ‘the canonical story of Modern British Sculpture is entirely premised on direct carving.’9 This approach, she argues, has resulted in a straight-jacketing of British sculpture because it ignores not only the wide variety of processes and techniques that modern sculptors often employed alongside carving but also the crucial place of the numerous and often nameless (at least in modernist histories) carvers whose work has not been discussed under the rubric of ‘direct carving’ because it was often carried out in the service of larger projects, such as sculpture on buildings. It also ignores the histories of the countless carvers who worked without public recognition in the employment of named ‘modern’ artists who received the recognition rather than the artisans and skilled labourers who assisted them in the manufacturing of their sculptures.10

If ‘direct carving’ and the associated concept of ‘truth to materials’ became doctrinally enshrined in historical accounts of the period, these were nevertheless lively and controversial issues for Moore as a young artist embarking on a career as a sculptor. It is also worth pointing out that Moore and his contemporaries were very much aware of the dominant hold of direct carving in discussions about sculpture: Moore later said, ‘Now I realise that it doesn’t matter how it is made but it mattered terribly then.’11 What, then, did direct carving mean for Moore when he first decided to take up chisel and mallet as a student? Why was it such a lively and noteworthy subject? According to Moore, he began carving in stone in 1920 and continued to do so, against protocols, when, in 1921, he went from Leeds Art School to the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. Moore’s recollection of his training in the sculpture classes very much sets up an academic versus modernist split over the practice and conception of carving, which largely revolved around those who copied when they carved and those who carved ‘freely’.12 Moore used the process of carving as an organising principal, splitting the carver-copiers and the carver-artists into two separate camps. At the Royal College of Art stone carving was taught by Barry Hart. Hart was, Moore tells us, ‘almost the same age as I was’, as if to underscore that the politics of carving was not a generational battle, but a pedagogical one, which was waged not simply between an old and a new guard but also amongst sculptors like Hart and Moore who were the same age. Hart had been appointed, according to Moore, ‘purely and simply because his family were professional stone carvers. They were not sculptors, but they could, by using pointing machines, copy sculpture.’13 Moore recounts how Royal Academicians would send plaster casts of highly finished portrait busts to the stone carving workshops where the minutiae of detail of the clay or terracotta model would be copied into marble or stone using a ‘pointing machine which would take measurements to within one thousandth of an inch.’14

There is something pretty cavalier about Moore’s assessment that Hart and his like were ‘not sculptors’, but this arguable division of artisan and artist, as Curtis and others have discussed, still holds sway today in discussions about modern sculpture.15 For Moore, this division was not about skill; Hart ‘could handle a hammer and chisel remarkably well,’ Moore tells us.16 It was about the issue of copying, authenticity and originality. Elsewhere, he expanded on this split, noting that:

The difference between a mason and a sculptor is that a sculptor is someone who makes his own ideas. A mason is someone who has technical knowledge of handling tools and how to make measurements and to enlarge, and that has nothing to do with his own ideas and vision – he is only carrying out someone else’s ideas. A sculptor is a sculptor not because he is adept at using wood carving tools or stone carving tools. His technique is his vision – or the mind behind it.17

Carving, therefore, was not simply a method or skilled process of making. To be technically proficient at using the tools of the stone carver was simply not enough in Moore’s eyes. It meant something more than mimetic reproduction of the artist’s idea in material. Today, however, it is sometimes difficult to fully appreciate the critical and cultural charge that Moore and others attributed to carving and the almost evangelical tenor attached to the debates about carving. But thinking about carving as something cultural and conceptual, as well as technical, helps to restore something of the aliveness and investments of these debates.

Henry Moore

Head of the Virgin after Rosselli 1922–3

Marble

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Head of the Virgin after Rosselli 1922–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Domenico Rosselli

The Virgin and Child with Three Cherub Heads 1450–98

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.5

Domenico Rosselli

The Virgin and Child with Three Cherub Heads 1450–98

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Moore was at college to do what he called ‘college work’ – work that was required of him in order to complete the teaching diploma he had registered on at the RCA. One of his earliest pieces of carving, Head of the Virgin (fig.4) can be seen as both the fulfilment of the diploma’s requirement to successfully copy a piece of Renaissance sculpture, in this case a piece attributed to Domenico Rosselli and titled The Virgin and Child with Three Cherub Heads (fig.5), and a playful and purposefully recalcitrant response to frustration he felt at being made to endlessly copy, which was something of standard pedagogic practice within art school training in the early twentieth century (especially at the RCA which drew heavily on the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum for teaching).18 Moore’s marble Head of the Virgin is not the primitivist-inspired, ‘free carving’ associated with Moore’s turn to ‘direct carving’ in the 1920s but it nevertheless has a lot to tell us about his growing commitment to the ideological basis of carving directly, as opposed to copying in stone using the intermediary device pointing machine advocated by his RCA tutors such as Barry Hart and the then Professor of Sculpture, Derwent Wood. Moore persuaded Hart to let him carve the piece without the aid of the pointing machine but had to add false pointing marks to the piece to convince Professor Wood that he had been a diligent student and executed the task as set out in the curriculum. As art historian Margaret Garlake has remarked, Moore chose to omit much of the detail of Rosselli’s carving, namely the background thick with an angelic host and also altered the Virgin’s mouth to give her a knowing, Renaissance smile from one angle, and an altogether more lopsided, petulant look from the other side. In its wilful omission of important detail and the addition of others (such as the fake marks of the pointing machine), it was a work to use Garlake’s phrase, of ‘conscious defiance’.19 With hindsight, the piece seems to openly mock its assessors through the proximity of the smooth surface of the Virgin’s halo and the choppy, hacked-off stony background left very visibly where there should have been three cherubs and its uneven smile. If stone could speak, surely this rough work surrounding the Virgin would say, ‘I am not a slavish copy’. Ultimately, carving for Moore, was not about copying but translating an artist’s ideas into the material without the intermediary of machine or mason. This, as we shall see, was a position that became difficult, even impossible, to hold fast to, but it was this vision of carving as direct, defiant and determined which shaped the narrative of the relationship of carving and British sculpture in the twentieth century.

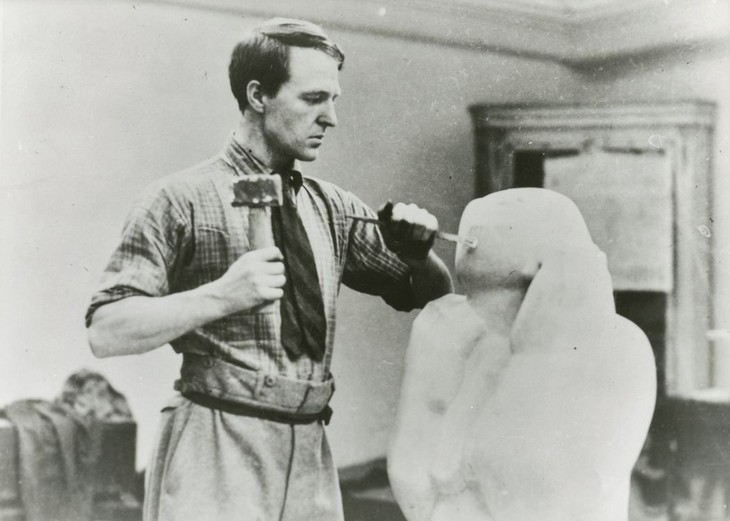

Carving as resistance

The notion that carving sculpture was a difficult process, not something easily translated via a machine, was something Moore was keen to stress in his comments on carving and the images taken of him at work in the studio. In an essay of 1960 in which he again returned to the early days of how he became a carver, Moore described how he began ‘by trying to make sculpture which should be as stony as the stone itself’ but afterwards realised that ‘unless you had some tussle, some collaboration and yet battle with your materials, you were being nobody. The artist must impose some of himself and his ideas on the material, in a way that uses the material sympathetically but not passively.’20 He chose Cornish Serpentine to make one of his first ‘freely’ carved sculptures and had to give up half way through as the stone was too tough.21 This very first ‘battle’ with the material had a profound effect on him and sometimes, he observed, carving felt like ‘you are fighting the material’.22 The notion of sculpture, and carving more precisely, as both tussle and collaboration, helped him to articulate his position as a carver-sculptor, a direct heir to the sculptors of the previous generation he admired, especially Epstein, Gill and Gaudier-Brzeska whom, he said, in 1932, had a ‘hard fight for the practice and recognition of direct carving’ and to whom his cohort of direct carvers, such as Barbara Hepworth, Leon Underwood and Frank Dobson, should thank for ‘the victory’.23 Undoubtedly, in these early comments on carving, Moore was drawing in no small part on the virile rhetoric for the sculptor-carver that had been developed by the earlier generation, and Ezra Pound’s writing on Gaudier-Brzeska in particular.24 Pound’s 1916 memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska was highly influential. For Moore, the text was ‘a great help and an excitement’ and he felt allegiance to the ideas of ‘a young sculptor discovering things.’25 It is not hard to imagine the call that the statements by Gaudier printed in Pound’s book, such as ‘[e]very inch of the surface is won at the point of the chisel’ and ‘every stroke of the hammer is a physical and a mental effort’, would have made to Moore as he was developing his own ideas about carving.26

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure 1938

Green Hornton stone

object: 889 x 1327 x 737 mm, 520 kg

Tate N05387

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The shape of some of his earliest stone carvings, such as Mother and Child 1924–5 (fig.2), perhaps betrays some of this anxiety that Moore felt before embarking on a piece of sculpture. Although the rectangular, blockish quality of Moore’s early work has often been interpreted as an adherence to a ‘truth to materials’ creed and a formalist choice for the shape of the quarried block of stone, there were also the issues of his skill and developing technique of carving directly into what could be unpredictable stones, often riven with marks, air pockets and veins made in the process of the hard press of geological formation. Looking back at this work much later in life, Moore recalled his trepidation at working in this way. The sculpture had, according to Moore, the ‘pressed, compressed sense of a block’, which ‘although monumental in a sense’, was a result of not having ‘enough command of direct carving to give the forms a full three-dimensional existence.’29 Stone offered ‘resistance’, a resistance that Moore claimed that he enjoyed working, but this way of working also presented the carver with challenges, choices and limits. Under the surface of what many have seen as a celebration of the physicality demanded by stone carving, Moore also signalled a certain anxiety about working with what could be unpredictable, and even dangerous, material. He was at times ‘frightened to weaken the stone’ which at times led to what he saw in later years as ‘an exaggerated respect for the material’.30

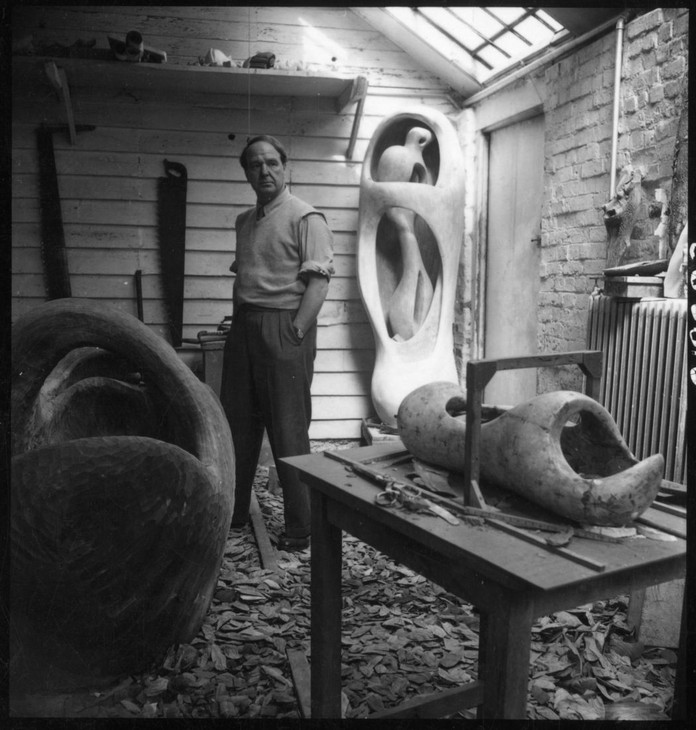

Carving an image

Photograph of Henry Moore at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Photograph of Henry Moore at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph of Henry Moore carving at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Photograph of Henry Moore carving at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Woman with Upraised Arms 1924–5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Woman with Upraised Arms 1924–5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Carving is in many senses a limited method (the carver can only push the material so far before it becomes weakened and likely to snap or break off), and it can also be limiting. Moore increasingly attached a great deal of importance to the studio and workshop spaces in which he worked, but at times he also felt being a carver rooted him to the spot. Writing to his friends, Raymond and Gin Coxon, he teased them with more than a spot of envy about what he perceived to be the mobile life of the painter in comparison to sculptors: ‘You painters, you can trot all over the globe and say it’s for work – I can’t lug lumps of stone all over the country, set a chunk down in the pleasant looking spot, tickle away on it for an afternoon.’33 However, the studio was not only a place of work, but a store of potential ideas and a repository for the ‘random blocks’ he would pick up on visits to stonemasons’ yards which would then sit in his studio ‘waiting for an idea that would suit the shape and texture of that particular stone.’34 These pieces ‘of good stone’ could occupy studio space for longer periods of time. As Moore observed, even when he came up with an idea that ‘would fit their proportions and materials perfectly, their size was wrong.’35 Carving was a waiting game.

Photograph of Henry Moore carving the West Wind 1928 on the façade of the London Underground headquarters

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Photograph of Henry Moore carving the West Wind 1928 on the façade of the London Underground headquarters

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Stone Figures in a Landscape Setting 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Stone Figures in a Landscape Setting 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Travertine marble

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Stone carving, as Moore was well aware, had long been a public art, and even though he had reservations about the ways in which sculpture on buildings was often treated by modern architects, he always had the longer history of carving outdoors in his mind. Huge monoliths and stone sculpture on great medieval cathedrals – powerfully-charged sculpture for ritual and religious purposes which he had encountered in institutions such as the British Museum in London and the Musée Guimet in Paris – these were always very much at the forefront of Moore’s cultural imagination when envisioning a role for his carved sculpture in the public landscape of the mid-twentieth century. Moore also worked through these ideas in drawings such as Stone Figures in a Landscape Setting executed in 1935 (fig.11). Large-scale commissions made at the height of his reputation, such as the UNESCO Reclining Figure 1957–8 (fig.12) in Roman Travertine marble, set against the architectural setting of the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris and yet released from what Moore saw as the tyranny of architectural dominance, demonstrate Moore’s commitment to these ideas about the public role of sculpture, especially in the context of the international politics post-war period. Such ideas about the universal humanism and palliative power of public art, as Lyndsey Stonebridge has pointed out, espoused not only by Moore but also by key supporters such as the critic Herbert Read, are responsible in part for why Moore’s work is seen by some today as nostalgic, overloaded with an ‘ideological turn to a late-romantic humanism, coupled with its political failure.’41 Direct carving is perhaps always in some ways always a nostalgic art; a turn back to a method of making to create works in the hope of a better sculptural, and in the case of the carving outside the UNESCO building, even political, future.

Carving networks

Photograph of Henry Moore and assistants at Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Photograph of Henry Moore and assistants at Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph of the Henraux Quarry 1958

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: David Lees, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Photograph of the Henraux Quarry 1958

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: David Lees, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Carving wood

Direct carving has become very much associated with stone, not only in the case of Moore but also with other carvers in the first part of the twentieth century. However, wood was an important material in Moore’s sculptural practice and conception of carving. Curator David Mitchinson acknowledged that although the total number of wood sculptures only represented a fractional proportion of his output but they nevertheless ‘show many vital aspects of his development as a sculptor.’49 Wood was the foundation on which his subsequent career as a carver was built. It was the material he carved into to make the Roll of Honour for Castleford Grammar School (fig.1), his alma mater, using woodcarving tools lent to him by the school art teacher who was to have a profound influence on him, Alice Gostick. This first recorded piece of direct carving that Moore did is significant, yet it is rarely written about in the narratives of modernist sculpture. That is perhaps because it does not easily fit into the category of modern sculpture with which Moore has most frequently become associated with. It contains no representational forms and no hint of the human form. The Roll of Honour was commissioned to record the names of all Old Legiolians, the name given to pupils of Castleford Grammar School, who served in the war’.50 This was a serious commission – one that would have perhaps instilled a sense of the public role of the sculptor’s craft even at this nascent stage of his career. Moore described it as the ‘first serious wood carving’ that he had executed.51 In 1917, he would serve on the Western Front in the Civil Service Rifles and later his own name would be added to the third column.

Moore stored great importance by the right kind of tool for the job. He wrote of carving in wood:

Wood carvers, and workers in wood, over the years have developed the tools that are most useful for dealing with wood. If you don’t use the right tools things take longer, so you learn which tool suits ... For carving in stone, the chisel is a flat one, but if you dig a tool inside the wood it can split it, so your tool has to be a curved gouge so that the two ends come out of the wood and don’t bury themselves in it ... You have to work in a slightly different way, too, and you may have to take off smaller pieces at a time.52

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.15

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

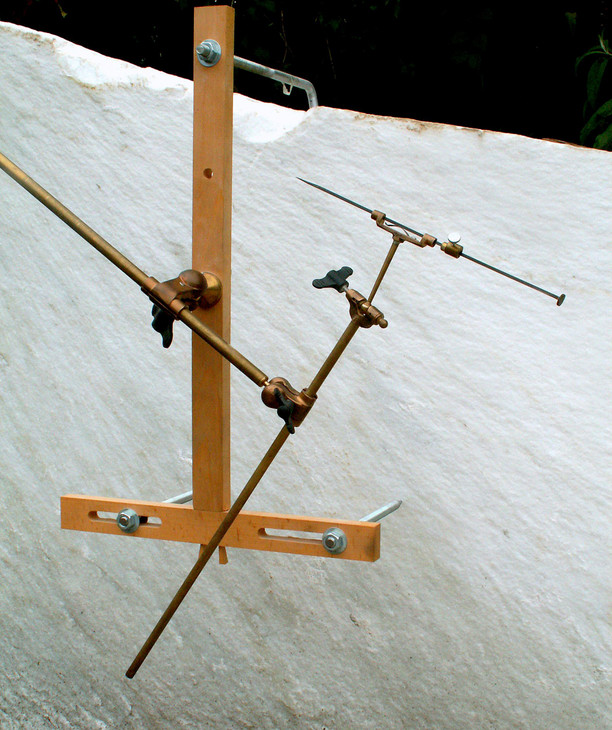

Photograph of Moore's tools

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Photograph of Moore's tools

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Herbert Read wrote in his introduction to his book on Moore in 1934 that what was important was ‘that the effects of one set of tools on one kind of material should not be imitated in another material by another set of tools’, it sounds as if he might be repeating verbatim something Moore had said to him – a snippet of the craftsman’s wisdom.53 Moore was also photographed with his tools, and made photographs of them (figs.15, 16). These images convey what the philosopher Richard Sennett, writing about photographs of tools in his book The Craftsman (2008), calls a ‘message of clarity, of knowing which act should be done with which thing.’54

Although he carved just six sculptures in wood after 1945 compared to the thirty-nine pieces he executed before the war,55 Moore’s series of large reclining figures carved from Elmwood was started in 1935 and culminated in 1978, suggesting that his interest in woodcarving should not be limited to one period of his career. When working on his final Elmwood sculpture in 1976 (Reclining Figure: Holes 1976–8, Henry Moore Foundation), he corresponded with a tool manufacturer. Although not able to help with the ‘major problem you have with your elm wood sculpture’, the manufacturers were able to recommend tools for cutting into non-wood materials such as ‘a carbide tipped circular saw blade for fitting to your Bosch machine and a carbide tipped handsaw which will cut concrete, marble, etc.’56 The nitty-gritty world of manufacture and tool supplies is rarely discussed by art historians. The make of the blades, the angle of the chisel, the lengths artists go to find the right tool – these details often remain within the walls of the studio. But these sculptures would not have been made without these tools; direct carving is done ‘by hand’, but only through the necessary use of the tools that transfer the action of the sculptor’s body into the material. These exchanges about tools between Moore and manufacturers, now preserved in his archive, also complicate the notion often upheld that ‘direct carving’ is also somehow antithetical to mechanisation. Moore’s early protestations about the pointing machine and the many images of him at work using only a hammer, chisel and his muscles have held such sway in discussions of sculpture and carving that they have obscured the way in which Moore and his assistants used mechanised and electrically-powered tools, especially to remove large pieces of wood and stone in the early stages. One only has to look carefully at the photographs to see the power cords.

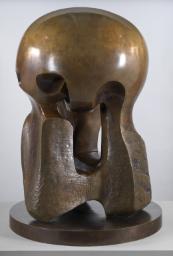

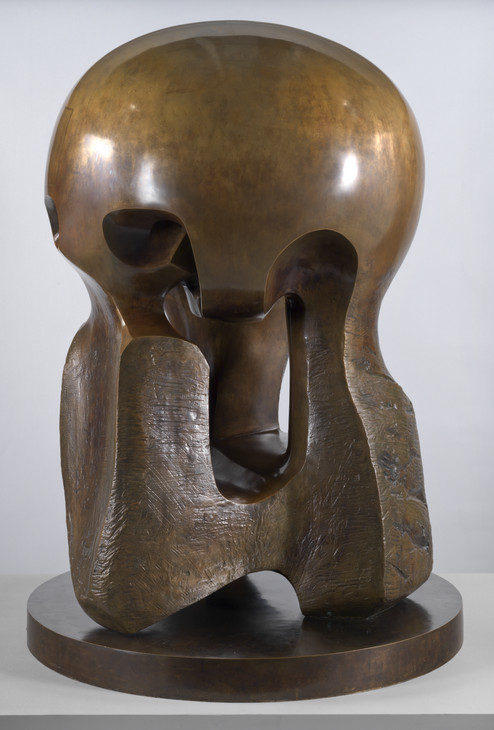

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Bronze

object: 1270 x 920 x 920 mm

Tate T02296

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore OM, CH

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Composition 1932

African wonderstone on oakwood base

object: 445 x 457 x 298 mm

Tate T00385

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Henry Moore OM, CH

Composition 1932

Tate T00385

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In both wood and stone Moore often left traces of the mark of the tool, especially the groves made by a claw. He also sometime carved into his plaster maquettes before they were sent to the foundry so that these physical marks of making would appear on the surface of works in bronze as can be seen in Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5 (Tate T02296; fig.17).57 The use of the tools was not just part the process of making for Moore but an essential part of the aesthetic appreciation of the finished piece. ‘In sculpture the surface textures should be the result of the way you make the piece, of the tools you use’, he observed in an interview in the 1980s.58 Moore thoroughly exploited the natural grain of wood in achieving the final form. Take, for example, Composition 1932 (Tate T02296; fig.18), where the dense rings of the African wonderstone coalesce around the prominent, round swellings, encouraging the viewer to follow the shape of the sculpture and move around the piece. Following the undulating grains of the wood also encourages our haptic sense of vision – in other words, looking evokes touching. This was certainly true for the first purchaser of Moore’s third Elmwood reclining figure, the surrealist painter Gordon Onslow-Ford: for him, the surface was ‘subtle and invited the touch.’59 Moore was tremendously skilled in using the grain of the wood and making it an essential part of the overall effect of the sculpture. Again, Onslow-Ford seems alive to these effects when he described walking around the sculpture and catching ‘the essence of well-loved rolling landscapes that had been transposed into anthropomorphic forms’. This fusion of natural material and the symbolic forms of Moore’s female figure had a powerful effect on the painter. ‘I felt that I was in the presence of the Mother Earth Goddess,’ he later recalled.60

Carving and the ‘world tradition’ of sculpture

John Russell, in his essay on Moore’s carvings written for the 1961 exhibition Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings at Marlborough Fine Art Ltd. in London, listed the materials from which Moore had made carvings between 1922 and 1939:

marble, Portland stone, Mansfield stone, Pynkado wood, Cumberland alabaster, ironstone, African wonderstone, Corsehill stone, Travertine marble, Ancaster stone, ebony, beechwood, Ham Hill stone, Horton stone, Hopton-wood stone, verde di prato, walnut wood, serpentine, Bath stone, painted slate.61

It is an impressive list of British, European and African materials. The ways in which Moore’s carving practice was connected with admiration for the sculptural traditions of Africa, Asia and the Pacific regions has been well documented, inspired by serious study in the British Museum and publications such as Roger Fry’s Vision and Design, which gave Moore a language of form to describe his emotional and aesthetic response to viewing African sculpture in particular and encouraged him in his rebellion from the strictures of academic sculpture as taught in the European art school system that he had come through. If Moore was persistently celebrated as an ‘English’ sculptor in his own lifetime and after, he consciously positioned his work on the global map of sculpture making at an early stage in his career. In 1926 he pencilled in his notebook: ‘Keep ever prominent the world tradition – the big view of sculpture.’62 Discussions of the primitivism of Moore’s carving have tended to focus on formal attributes, drawing similarities between his works and those often found in the ethnographic collections on the British Museum in an empirical search for direct comparisons between shape and form. For example, the exhibition and accompanying catalogue Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, held at Leeds City Art Galleries in 1982, placed sculptures such as an Aztec carving of a seated man from 1400–1500 A.D. from the British Museum alongside Moore’s Maternity 1924, in Hopton Wood stone.63

These sculptural researches in the museum were undoubtedly of tremendous important to Moore as he was developing his ‘big view of sculpture’, but art historical accounts often fail to mention the geo-political networks of colonialism which made such comparisons possible in the first place. However, in Moore’s notebooks and memoirs, traces of empire are most certainly there. Going back to Russell’s list of materials, we are made aware that it was not just subject matter that Moore was sourcing from other cultures but materials, too. Moore told an anecdote about acquiring some ‘samples of wood from the Commonwealth which were being discarded by the Natural History Museum, where I knew the Director.’ In this colonial cache, from which he made Standing Woman 1923 (walnut wood, City Art Gallery Manchester), they were also examples of wood from many of the British colonies. Such survey collections of the natural resources of the empire were popular in museums in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet in an erosion of place and identity common in the narratives of British colonial attitudes to imperial territories, Moore recalled that he was not told the name of this dense, hard, resinous and heavy wood and so ‘could only call it dark African wood.’64 Temporary exhibitions were also an important feature of the imperial cultural landscape of London well into the twentieth century and these also provided Moore with access to carving from across the globe. In 1951, during the Festival of Britain, an exhibition called Traditional Art from the Colonies was held at the Imperial Institute, sponsored by the Colonial Office. Moore was interviewed while visiting it. African tribal carving, he said, should ‘be preserved from destruction so that it can be put on show in wonderful exhibitions like this – here and in the colonies – to teach young artists what real vitality is’.65 Moore was speaking at the Imperial Institute, which was established at the end of the nineteenth century as a result of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, at an exhibition held under the auspices of the Festival of Britain, itself an event re-imagined for the twentieth century in the long line of Victorian great exhibitions and world fairs. Such a moment – a British sculptor surrounded by African sculpture in an imperial exhibition in London – reminds us that the correspondences between British sculpture and the rest of the world are always about much more than shape and form. As he gave this interview, Moore might have also cast his mind back to the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924 in which he had been involved as a student, carving some heads in plaster for the cotton exhibit.66 Whilst there, he also apparently viewed some African sculptors at work and admired their tools, especially the use of the adze (a tool similar to an axe used in many cultures since ancient times). The somewhat conservative focus on direct carving as a ‘native’ craft tradition of the British Isles fails to confront the ways in which the practice of carving in early twentieth-century Britain was shaped conceptually and materially not only through the supposedly ‘liberating’ visits made by the young western artist to the colonial museum but also through the very real and asymmetrical networks of the British imperial system. These brought carved objects and materials and also sometimes the sculptors who made them to the imperial centre, to be put on display.

On carving: writing about making and process

Moore wrote in 1937, ‘It is a mistake for a sculptor or a painter to speak of write very often about his job. It releases tension needed for his work.’67 However, many people asked him about his work, and, polite and well-mannered, he probably often felt obliged to respond. But, he also, I think, felt an obligation to communicate something about how he conceived of a role for the sculptor, and especially the modern sculptor-carver, in the twentieth century. Moore’s published statements on the act of carving give a sense of the importance and deep belief he attributed to it. Of these early statements, some appeared in specialist journals, such as his first article printed in the Architectural Association Journal in May 1930, but others were contained within the pages of more widely circulated, less art-world oriented periodicals such as the Listener and the New English Weekly. These set the terms of much of the debate that has shaped our understanding of modern sculpture in twentieth-century Britain, especially in the ways that carving was pitted against modelling, and sculpture in the round was exalted above the commercial doggerel of the architectural relief.

The ‘On Carving’ article published in the New English Weekly was subtitled, in brackets as if not to remove the force and focus of the main title, ‘(A Conversation: Henry Moore and Arnold Haskell)’. In the tradition of artist-in-conversation pieces, the questions and answers are batted back and forth with something of a formality and stiffness that may, or may not, have been present in the actual circumstances of this ‘conversation’. Halfway through what is a relatively short exchange, Moore appears to take control of the direction of the dialogue. His words are recorded thus: ‘Perhaps I can explain more clearly some of my ideas about carving by telling you something of my own development.’68 Here, Moore wraps together his ideas about practice with his own biography. The anecdotes about Moore and carving are many and, thus method becomes something intimate and personal. Moore is making clear that these are not abstract, academic thoughts, but part of the very fabric of his life. He looks back over the first, fleeting decade or so of his becoming a sculptor. ‘When I started carving about twelve years ago my work had this limitation of relief,’ he tells Haskell, and after a series of experimentation, he arrives at a ‘realisation of block rhythm instead of only linear and surface rhythm.’ The article is also a narrative of the influences and interests that Moore wanted to emphasise in his development as a carver. First, there is nature and pebbles, flints, stones and bones gathered from the beaches of Norfolk and viewed in the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London. ‘Of course one does not just copy the form of a bone, say, into stone, but applies the principles of construction, variety, transition of one form into another, to some other subject – with me nearly always the human form, for that is what interests me,’ he is noted as saying, setting out the patterns of influence and also setting the record straight. He pays his dues to other artists, too; the ‘Negro’ sculptors who remains nameless, but from whom he has learnt ‘the full realization of form in the round’ and Jacob Epstein, who is mentioned more than once, exalted here with the artistic power of ‘imbuing with life whatever he touches, bronze or stone.’69

There is, as with much of Moore’s observations on sculpture, a matter-of-factness about his views recorded in ‘On Carving’ that he was keen to promote in much of his writing throughout the course of his career. He is eager to not get distracted and wander along conversational tangents – and when he is at danger of doing so, he says to Haskell that he will ‘return more concretely to your question.’70 Somewhat fittingly, the article ends with a discussion of materials and materiality. Haskell wants to know how far a carver is ‘bound by his materials’. The carver, replies Moore, should not force his materials or ‘weakness is the result.’ He continues: ‘At the completion of the work the material should retain its own inherent qualities. Sculpture in stone should look like stone, hard and concentrated. To make stone look like flesh and blood, hair and dimples, is coming down to the level of the stage conjurer.’71

This language of the ‘hard’ as opposed to the ‘weak’, the conception of a ‘truth to materials’, and the vision of the carver-sculptor as somehow more noble than the ‘stage conjurer’ modeller that Moore mobilised in the 1930s inherited much from his predecessors, especially Epstein and Gaudier. The language of carving in relation to Moore’s work was developed in particular by two contemporary writers, and close associates, Herbert Read and Adrian Stokes. Carving and stone played a central role in their discussion of Moore’s work.

Read authored the first monograph on Moore in 1934 when he was also editor of the Burlington Magazine. The book, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawing, was a collaboration between the Yorkshire-based firm Lund Humphries and Anton Zwemmer in London. This landmark text, which was the foundation of the first catalogue raisonée of Moore’s work, emphasised Moore’s work as a carver. The list of illustrations was divided by material, with fifty-six stone sculptures coming first, followed by a section on terracotta and concrete sculpture, then sculptures in wood. Next came plates of Moore’s stringed figures, then sculpture made from metal, and the final section was dedicated to sketches and drawings. Read’s text presents Moore’s carving as a hybrid negotiation of abstraction and figuration, situating it both within a global history of form (Read was heavily influenced by the German writer on aesthetics Wilhelm Worringer) – within the space of two consecutive pages Read cites examples from Cycladic Greece, West Africa, Roman Britain and Mexico – and alongside the work of contemporary avant-garde artists in Europe, especially Brancusi and Naum Gabo. Read conceptualised Moore’s practice as one of essentially a negotiation between idea, material and form: ‘The aim of a sculptor like Henry Moore is to represent his conceptions in the forms natural to the material he is working in. I have explained how by intensive research he discovers the forms natural to his materials. His whole art consists in effecting a credible compromise between these forms and the concepts of his imagination.’ (The italics are Read’s own.)72 Vitality was a key word for Read in trying to articulate these relationships.73 Moore also wrote that he wanted to make work with a ‘vitality of its own’74 and to ‘make sculpture as big in feeling and grandeur as the Sumerian, as vital as Negro as direct and stone like as Mexican as alive as Early Greek and Etruscan as spiritual as Gothic’75. For both Moore and Read, it was through the process of stone carving that a modern art could be vital, big, direct and spiritual all at the same time. The job of the artist, they believed, was not to impose form on material but to release an inner vitality contained within the block of stone.

Drawing conclusions

If stone presents the carver with many practical considerations before work began, wood is by no means an easier option. The drying-out process of a piece of timber must be thorough to avoid cracking at a later stage. Moore worked on his Elmwood sculptures in incremental stages to allow the inner layers of this wood, which was then the largest timber native to the British Isles, to dry out. Again, this was not work that could be ‘thrown off’ in an afternoon. Carving is a slow process but Moore was also quick as a visual artist. Creative ideas came to him thick and fast (over fifty in one afternoon was not uncommon). Why would such a speedy, spontaneous visual thinker put so much effort into carving? Why make the methodical, rhythmical thud-thud-thud of the carver’s mallet on the round and smooth head of the chisel the chief way of making art?

There is perhaps something to be said about the tension, or to go back to an earlier point, the discipline, between the speed with which Moore generated ideas and the primary mode through which he chose to execute them. Moore had ways of dealing with a build-up of ideas. As Anne Wagner has recently written, Moore used drawing to mediate between getting the idea and selecting it to be further worked on. As she notes, he had so many ideas that he had to work out a process for getting rid of a few. ‘Hence,’ she writes, ‘we should consider the artist’s process as aiming not only to collect but also to eliminate; it was comparative as much as accumulative, reflective as well as productive, and relied on the artist’s critical relationship to his thought and work.’76 Each piece of carving did not exist in isolation, but was part of a process of idea making, selecting, rejecting, reusing and refining that relied on other processes, especially drawing, but also modelling and writing, too. Moore’s copious sketchbooks and drawings are full of connections to his carved works; he also drew on his sculptures to make graphic marks to guide the placement of his chisel.

It now seems surprising that in 1961 John Russell would worry that Moore’s carving might be under appreciated and that Moore would be seen as ‘essentially, or predominantly, a sculptor in bronze.’77 At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the opposite was true for Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell who argued that, in fact, it was his carvings that had been singled out from the rest of Moore’s practice. They stated that carving is privileged as significant in histories of Moore’s work ‘because of its combination of strength, action, trace and incision on the material, and for its associations with the virtues of craftsmanship and a notion of honest labour, concepts all tied to masculine subjectivity.’78 Admittedly, a lot that can be said about Moore and carving now sounds like truisms, but it is important, I think, also to place carving and writing about carving in context. In the early and mid twentieth century, these claims about the ethics of carving rang out with a radicalism and critical force which it is perhaps all too easy to be cynical about today. Moore’s carving practice needs to be viewed within the cultural and critical formations of which it was a part.

Notes

See in particular Penelope Curtis, ‘How Direct Carving Stole the Idea of Modern British Sculpture’, in David J. Getsy (ed.), Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, c.1880–1930, Aldershot 2004, pp.291–306.

http://www.henry-moore.org/pg/interactive-tours/virtual-perry-green/buildings/g , accessed 14 February 2014.

This phrase is Anne Wagner’s. See Anne Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, p.16.

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, p.69; selected quotes of Moore’s from this publication are reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002.

See Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1982, and more recently Rupert Richard Arrowsmith, Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde, Oxford 2010.

Henry Moore in Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture, commentary by Henry Moore, photographs by Gemma Levine, London 1983, p.17.

‘We all began to believe that carved sculpture was better than modelling’. Henry Moore in Wilkinson 2002, p.231.

See also Charles Harrison, ‘Sculpture and the “New Movement”, in Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, , exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981. Harrison points out that carving was also practised by many sculptors that were not considered to be ‘modernists’ who often associated with and exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, but also ‘the persistence of monumental and ecclesiastical carving’. Harrison, p.103.

It is worth pointing out that this division was a professional, not a personal one. Barry Hart was Moore’s best man. Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, London 1987, p.63.

I have drawn on Margaret Garlake’s detailed discussion of this sculpture and its exhibition here. See Margaret Garlake, ‘Two-Faced: Henry Moore’s Head of the Virgin, 1922’, Sculpture Journal, vol.15, no.2, 2006, pp.269–72.

Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor’, Horizon, 1960, in Wilkinson 2002, p.202.

For more on the issue of modernist sculpture and masculinity, see David Getsy, Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905, New Haven and London 2004; Lisa Tickner, ‘Now and Then: The Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.16, no.2, 1993, pp.55–61; and the author’s work on Gaudier-Brzeska and wresting, Sarah V. Turner (ed.), In Focus: Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965, by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, July 2013, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/gaudier-brzeska-wrestlers , accessed 30 January 2015.

Henry Moore quoted in Henry Moore Looking at his Work with Philip James, London, New York and Toronto 1975, p.

Jon Wood, ‘A Household Name: Henry Moore’s Studio-Homes and Their Bearings, 1926–46’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.17–42. See also Jon Wood (ed.), Close Encounters: The Sculptor’s Studio in the Age of the Camera, Leeds 1999.

Henry Moore, Letter to Gin and Peachum (Raymond) Coxon, 3 September 1933, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Henry Moore quoted in Richard Cork, ‘Overhead Sculpture for the Underground Railway’, in Nairne and Serota 1981, p.98.

‘Sculpture in the Open Air’, a talk by Henry Moore, British Council, London 1955, in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.97.

Margaret Garlake has explored Moore’s shifting relationship to architectural commissions from his wary reserve to a firm believer in the social power of public art. She suggests that this was in no small part due to the influence of Herbert Read. See Margaret Garlake, ‘Moore’s Eclecticism: Difference, Aesthetic Identity and Community in the Architectural Commissions 1938–58’, in Beckett and Russell 2003, pp.173–93.

Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘A Love of Beginnings: Henry Moore and Psychoanalysis’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.42.

This very hard stone was chosen as Moore originally thought that the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which had intimated it wanted a large work from him, might buy the sculpture. Robert Melville (ed.), Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites, recorded by the British Council, 1955, in Berthoud 1987, p.208.

Henry Moore quoted in Carlton Lake, ‘Henry Moore’s World’, Atlantic Monthly, vol.209, no.1, January 1962, p.42–3.

David Bangham, Marketing Manager, Finished Product Division, letter to Henry Moore, 15 March 1976, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

I should like to thank Emma Stower, Archive Manager at the Henry Moore Foundation for suggesting that I also think about Moore’s ‘direct carving’ in plaster.

John Russell, Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carving, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art Ltd. London 1961, p.7.

Henry Moore Sketchbook 1926 (facsimile edition reproduced by Daniel Jacomet and Cie), Paris 1976. The original is in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, p.20.

Sarah Victoria Turner is Assistant Director for Research at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London.

How to cite

Sarah Victoria Turner, ‘Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www