Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions

Pauline Rose

Moore’s greatest market was in the United States where he had an influential network of supporters, who saw him as the quintessential Englishman. In the Cold War years his monumental bronzes also provided civic and corporate managers with highly visible symbols of citizenship and leadership.

When considering the acquisition of a sculpture, Henry Moore’s American patrons, whether civic or corporate, shared broadly similar expectations and hopes. Architects, chief executive officers and city mayors alike understood the cultural cachet that came with such a sculpture and how it could be used to improve responses to their buildings, products and ideas. If reservations were expressed concerning the choice of Moore rather than an American sculptor for such commissions, his presence at preparatory meetings or unveilings would almost without exception quell misgivings, such was his charm and warmth. Additionally, the nature of Moore’s sculptures – not explicitly figurative, yet not entirely abstract because of their references to the body and landscape – proved a highly appropriate form of public sculpture in the context of the immediately post-war and Cold War years. Notwithstanding Moore’s leftist leanings, the works offered no overt political content and, radically different from the type of figurative monuments associated with fascist and communist regimes, were promoted as symbolic both of Western democracy and, in their representation of humane qualities, civilised values in general.

An important factor in Moore’s success in the United States was his public image. American journalists tended to emphasise his working class origins when this suited their themes but also just as frequently described him as the perfect English gentleman. Reporters who saw him at his home and studio in Perry Green were also favourably impressed by his domestic environment and life with his wife and daughter. In 1946, after seeing Moore’s solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), an American reviewer visited the sculptor at home and recalled the ‘deep pleasure of knowing the man himself – kind, sincere to a rare degree in a veiled society, alive with ideas and strength, undidactic, in short with all the seldom encountered marks of greatness.’1 Such characterisations of Moore as an extremely personable and even admirable figure featured in a broad spectrum of publications in the post-war years, from art journals and documentary films to mass circulation magazines and newspapers, while photographs of Moore and of his home and sculptures regularly appeared in American mass media journals such as Life, Look and Vogue.

The rise of Moore did not pass unnoticed, of course. In 1967 the art critic Hilton Kramer observed that Moore was the first choice when American institutions were searching for a monumental sculpture to place in or alongside new buildings. The appeal of his work resided, Kramer wrote, in its ‘massive but gentle forms, its bronze glitter and high-style rhetoric, its quality of being at once eminently modern and yet vaguely traditional – that makes it the inevitable choice of civic-minded patronage. Not every such patron manages to get himself a Moore, but everyone seems to want one.’2 This essay aims to explore how a son of a Yorkshire miner came to be the acceptable face of modern art in the minds of key opinion makers and leaders in the civic and corporate spheres in the United States, using narratives of commissions in four major American cities – New York, Chicago, Dallas and Washington D.C. – as case studies.

Sculpture, urbanism and the art of business

American cities have long been conceived as sites of cultural and civic ambition. In the early twentieth century the City Beautiful Movement, for example, sought to refashion and enhance modern cities, and found supporters among local leaders of business and industry.3 In the post-war years there was again much discussion about the nature of public space and about how to improve the quality of city life. Public sculpture, it was thought, could play a central role in these endeavours, and in the 1960s and 1970s cultural developments became overtly linked with urban regeneration plans.4 Attempting to rejuvenate downtown areas and counter the flight to the suburbs, city mayors saw the commissioning of public sculptures as a means of bringing open spaces to life.5 Parks were prime sites for attempts to conceive the American city as a positive, enlightened entity. Early rhetoric about city parks had largely been philanthropic but businessmen quickly realised how their own interests could be served by their involvement in civic culture in public spaces. By the 1960s, however, parks in major cities had become seen as potentially dangerous places and among many possible solutions to this problem the installation of monumental sculptures was thought by some to be likely not only to adorn but also to humanise, and thus generate public respect for, such spaces.

As will be seen, civic and corporate tastes and aspirations came together in a remarkable way in the commissioning of sculptures by Moore for major public sites in cities in the United States. Influential individuals in both spheres (and they often came together in the boards of art museums) promoted the idea of art as adornment and emphasised the value of its integration into contemporary life. The influence of, and relationships between, such figures encouraged other, less wealthy private collectors to purchase Moore’s sculptures for their homes and offices (the taste that was being encouraged for the domestic sphere was easily transferred to the working environment, the ‘home’ for most people for the greater part of their day).

In corporate offices, however, the display of artworks often represented more than the exercise of good taste – it became a marketing tool, linked to the company mission statement. A number of businesses produced in-house journals that by the 1940s included high quality colour reproductions of artworks. Free and printed in large numbers, these journals reached many people who never visited galleries or museums and promoted an appreciation of (corporation-approved) art on a hitherto unknown scale. In 1956 Art in America published a special issue on the theme of ‘Art and Industry’ where it was stated that ‘the modern corporation is still quite surprised (and in many cases not a little pleased with itself) to find its members meddling in the affairs of culture.’6 In such ‘meddling’ businessmen often co-opted art world clichés for their own purposes. In 1969 a former Chairman of the Board at the Sinclair Oil Corporation described an artist as ‘the prototype of the free-questing individual ... in his works we find the nearest reflection of the human condition, its tensions and its direction. Where there is a vigorous artistic life, innovation, experiment, and challenge irresistibly communicate themselves to every other segment of society. Without these qualities, business would lose its forward thrust.’7 The innovations of avant-garde art supplied companies with a model for the promotion of themselves as progressive organisations, which helps explain why corporations were more interested in acquiring contemporary art rather than seemingly more conventional works by the old masters.8 At the same time, the growing sophistication evident in the modes of display within the retail sector was noticed among museums: sometime before 1970 a president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art apparently asked ‘a group of department store executives to remember that their influence was far greater than that of all the museums combined ... urging them to become missionaries for beauty.’9

The Rockefeller family vividly demonstrates the overlapping of cultural, political and business concerns so prevalent among business leaders in the United States. Born to one of the richest families in the world, Nelson Rockefeller was a businessman, philanthropist, public servant and politician, serving as Governor of New York from 1959 to 1973 and as Vice-President from 1974 to 1977. His mother was one of the founders of MoMA and he became its President in 1939. At the time of Moore’s exhibition there in 1946, Rockefeller, who was a great collector and patron of the arts, struck up a long-lasting friendship with the artist. Aware of the political impact of cultural affairs, Nelson later praised the activities of the British Council in facilitating cultural exchange, describing it as ‘a subtle yet powerful means of propaganda’.10 His brother David also supported the involvement of business in the arts, saying in 1966, ‘bankers and businessmen from the Medici to the Mellons have often been enthusiastic patrons of the arts’. Having ‘developed ideals and responsibilities going far beyond the profit motive [the modern corporation] had become ... a full-fledged citizen, not only of the community in which it is headquartered but of the country and indeed the world.’11

New York

The vision for the Lincoln Center originated in 1955 with plans to clear a slum area to create a performing arts complex ‘that would have seemed praiseworthy even to a high Renaissance Venetian doge.’12 The Centre’s President, William Schuman, declared that the project existed because ‘leaders of the arts, education, business, labor, the professions, philanthropy and government ... believe that the arts are a true measure of a civilisation’,13 and inevitably a major Moore bronze was considered for the new development.

View of Henry Moore's Reclining Figure 1963–5 at the Lincoln Center, New York 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.1

View of Henry Moore's Reclining Figure 1963–5 at the Lincoln Center, New York 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

At one point Shuman was alerted to the possibility that Moore might also be considering other commissions, at the Seagram Building, Chase Manhattan and the new Columbia University Law School Building (the latter was realised in October 1967). The Committee reluctantly began to consider alternative sculptors but Schuman recalled this as a ‘most discouraging exercise. While Moore had been selected unanimously and enthusiastically, finding a replacement was just the opposite.’ It was impossible to agree on an alternative. Frank Stanton – a broadcasting executive, member of the Lincoln Center Board of Directors and chair of the Art Committee – persuaded Moore to visit New York to see the proposed setting at the Center. He remembered everyone doing all they could to encourage Moore to accept the commission and not take on another work in the city. He wryly observed in a letter to Schuman that it had been interesting to see the architects and Committee members ‘work on’ Moore.19 In the event Moore was talked out of the Seagram commission by Bunshaft, who characterised Philip Johnson’s vision of a sculpture for each pool in front of the Seagram building as being like ‘two candelabras.’20

The difficulties were not over. When Moore’s sculpture arrived, Stanton received a telephone call from Newbold Morris, Head of the Parks Commission, who said that ‘he wanted that junk out of there the next morning! I ... told him who the artist was. Didn’t make any difference. That was on city property and he wanted it out. He threatened to have it removed the next day.’ Stanton replied that, if this happened, he would have every television station in the city there, and the dispute was quietly dropped.21

While Moore’s most significant British supporters were university-educated men, typically, art historians, writers and publishers, many of his key American champions were businessmen. George Ablah made his fortune in oil and property and started an art collection in his middle age. (He had reluctantly accompanied his daughter on a trip to Rome where he saw Michelangelo’s Moses and, reportedly disappointed at being unable to purchase this, he started to explore art galleries when he returned to America.) From his friends Ablah knew that Moore’s work was admired around the world and was well represented in museums; the breadth and depth of publications on Moore probably played a part in underpinning his enthusiasm for the sculptor’s work. Ablah saw an opportunity to share his newfound enthusiasm with others by showing his Moore sculptures in public sites. When interviewed in 1985, Ablah described the Moore sculptures in public places as functioning as ‘loss leaders’: he hoped that people would see the sculptures in parks and then want to go into a museum to see more.22

Flying by Concorde with David Finn from the public relations firm Ruder Finn and a close friend of Moore’s, Ablah travelled to England to visit Moore at Perry Green in 1983. Shortly afterwards Ablah sent agents all over the world to scout out available works, and bought one hundred pieces for his collection (to avoid raising the market price, the works were reportedly purchased in just ten minutes). Ablah wanted ordinary people to have the opportunity to see art, and suggested to the mayor, Edward Koch, an exhibition of Moore’s works in the parks of New York’s five boroughs in 1984.23 Koch responded favourably to the proposal but worried that this would be an expensive project because of the need for guards, fencing and insurance. Determined to avoid delays, Ablah paid for these additional costs himself. He knew that having low security was a risk as any damage to the sculptures would be bad for New York’s reputation and would ‘prove once and for all that all of its open, public places are jungles, and therefore, New York itself is literally a jungle’. By contrast, a successful exhibition without major damage would be ‘an event worthy of a standing ovation’.24

View of Henry Moore's Reclining Figure: Angles 1979 in the Doris Freedman Sculpture Plaza, New York 1984

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

View of Henry Moore's Reclining Figure: Angles 1979 in the Doris Freedman Sculpture Plaza, New York 1984

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although there had been a minor amount of graffiti on the works, the park authorities were impressed by the overall success of the project and the number of visitors.28 Mayor Koch was quoted as saying, ‘Isn’t it wonderful? Now, if we can only do that for the trains.’29 At the end of the exhibition Ablah donated to the city Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure: Points 1969–70 that had been sited in Central Park’s duck pond. In the following year, however, the New York Times reported that the sculpture’s raft had come loose and floated to shore; no attempt to remedy this was made as the six-month period granted by the Art Commission for the sculpture to remain in the duck pond had passed.30 The sculpture became covered in bird droppings, and this situation continued for several years much to Ablah’s concern. Writing to Finn in 1989 he said that he would like to remove it from the park and find another suitable site.31 The Art Commission approved the removal of the work in 1989 but where it went remains unknown, a somewhat inglorious end to the successful promotion of Moore in New York.32

Chicago

The acquisition of a major Moore sculpture for the University of Chicago in 1967 took place in the context of a notorious local scandal, that of the alleged misuse by the Art Institute of Chicago of the Benjamin F. Ferguson Fund for Sculpture in Chicago. Ferguson was a wealthy Chicago businessman who made a fortune in lumber and bequeathed a one million dollar endowment fund for the erection and maintenance of public sculptures in the city. Having travelled through Europe he was impressed with the statuary that he saw in fountains and squares, and wanted to see the same in Chicago. At its inception in 1905 the Fund was the largest such bequest made to any city in the world and thus it was expected that within a generation Chicago would become the most beautiful city in the world.33

The early faith that had been placed in the Art Institute’s handling of the Ferguson Fund was severely tested when on 22 May 1933 the Institute controversially sought a reinterpretation of Ferguson’s will.34 It wanted to use income from the Fund to undertake a major building project and successfully argued that the word ‘monument’ could be interpreted as an extension to the Institute itself. Newspaper coverage was scathing, arguing that this represented ‘the low ebb of appreciation for sculpture in public life.’35 Over subsequent years the funds accumulated and no sculptures were commissioned. In 1955 the Art Institute asked the court to consider a five-storey administration building to be paid for from the Fund, and in 1958 the Benjamin F. Ferguson Memorial Building was opened.36 An even more precise stipulation in Ferguson’s will had been his wish for the creation of public sculpture that commemorated important events in American history. However, money was spent on sculptures which did not take the form of traditional figurative memorials: in the early 1980s the observation was made in a guide to the city that the donor’s wish ‘had been winked at as surely, if not as audaciously, as it was in the construction of the Art Institute’s Ferguson Wing.’37

Moore’s Nuclear Energy 1964–6 (fig.3) was the first sculpture to be commissioned after the controversy over the Institute’s extension and thirty-five years after the previous Fund commission. Unusually within Moore’s work, the sculpture commemorated an important event. On 2 December 1942 Italian-born American physicist Enrico Fermi, working in a converted subterranean squash court on the University of Chicago’s campus, carried out the first controlled nuclear chain reaction that led to the atom bomb and the development of nuclear energy. While the working model was referred to as Atom Piece, the final sculpture was titled Nuclear Energy in order to emphasise the positive rather than the destructive aspects of the scientific breakthrough. This lack of clarity in the nature of what was being celebrated or remembered through the sculpture was echoed in the ambiguity of Moore’s own position in relation to this work as he was a lifelong supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and ‘ban the bomb’ movement.

William McNeill, then Professor of History at the University of Chicago, chaired the committee established to commemorate Fermi’s achievements as the twenty-fifth anniversary approached. Events did not run smoothly: there were issues with both fund-raising and the ownership of the land on which it was proposed to site the sculpture. Moore already had a strong reputation in Chicago, having many sculptures in various collections,38 and was then attracting a high level of publicity through the screening of films about him in the city.39 Writing in January 1964, McNeill informed Moore that the University had approved the committee’s recommendation to invite him to create ‘a statue that might body forth the awfulness of the event ... I mean awful in its proper sense: of inspiring awe ... a sense of greatness, power and danger all at once.’ McNeill said that the sculpture would be located about half a mile away from the actual place where the first chain reaction took place, on the Midway, a broad park-like thoroughfare dividing the University campus into its northern and southern halves.40 In fact, the sculpture was sited on Ellis Avenue, which crosses the Midway. Set back from the road, it was not in a particularly prominent position. It was close, however, to the Regenstein Library that was built at the same time by architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and it is possible that Nuclear Energy was seen as also providing an artwork for that project, particularly given the friendship between Moore and the architect Gordon Bunshaft.

The Fermi Memorial Planning Committee was concerned about the risk of public criticism of the sculpture but believed that this could be countered by ‘an appropriately-worded plaque’ hung nearby and care with the language used in the dedication ceremony.41 Whether a negative response was feared because of the sculptor or the sculpture’s subject is unclear, although the latter seems more likely given the sensitivity of the event being commemorated. In November 1967 McNeill informed Moore that the Ferguson Fund would finance the sculpture, with a grant of $200,000 and the rest being raised through public subscription.42 An exhibition of seventy Moore sculptures and about twenty-five drawings sourced from local private collections was also organised for the same period. Titled Chicago’s Homage to Henry Moore, the exhibition was held at the university for three weeks in December,43 and one journalist claimed that the size of this show demonstrated that Moore was the greatest sculptor represented in Chicago art collections.44

Local newspaper coverage of the unveiling of Nuclear Energy on 2 December 1967 set out the challenges the work presented: ‘Moore champions symbolism. Some scientists see in the atomic cloud the menace of destruction. They believe this to be the wrong interpretation to be placed on the work of Fermi. Humanists concede the militaristic aspect of the design but point to its cathedral effect and its suggestion of a hopeful future ... Thus, Henry Moore touches a sensitive nerve.’45 It was noted that Moore likened the Carrara marble mountains in Italy to cathedrals and that now he had ‘embodied the cathedral theme as part of his “Nuclear Energy” work, counterpointed against a mushroom cloud to reflect hope and despair in the nuclear age.’46 Moore later acknowledged the work’s evocation of a mushroom cloud but claimed in an interview that ‘in deference to the public nature of his commission he made it a very friendly atom bomb’.47

View of Henry Moore's Sundial (Man Enters the Cosmos) 1979, at the Adler Planetarium, Chicago 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.4

View of Henry Moore's Sundial (Man Enters the Cosmos) 1979, at the Adler Planetarium, Chicago 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

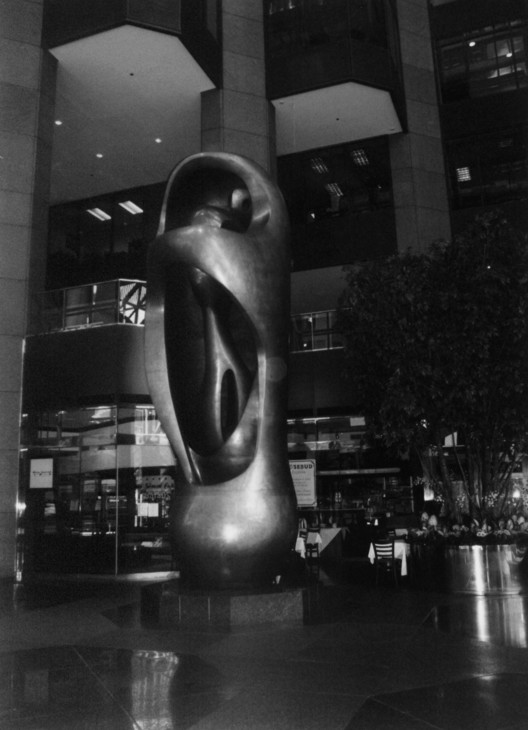

View of Henry Moore's Large Upright Internal/External Form 1981, in 3 First National Plaza, Chicago 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.5

View of Henry Moore's Large Upright Internal/External Form 1981, in 3 First National Plaza, Chicago 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Office lobbies in the 1950s had increasing security problems, their social function having all but disappeared, but it was recognised that a new identity for the building could be created through a large artwork.53 Chicago was the source of a 1973 publication called Lobby Art and Plazas where it was noted:

The long time railroad buff knows that there is a grain of truth in the adage ‘always polish station side’. This refers to the need to keep at least one side of a passenger train sparkling clean: the side seen by the customers. Building managers don’t have to be told how important it is to keep their lobbies sparkling. The first impression each visitor experiences often affects the way he will feel about your entire building.54

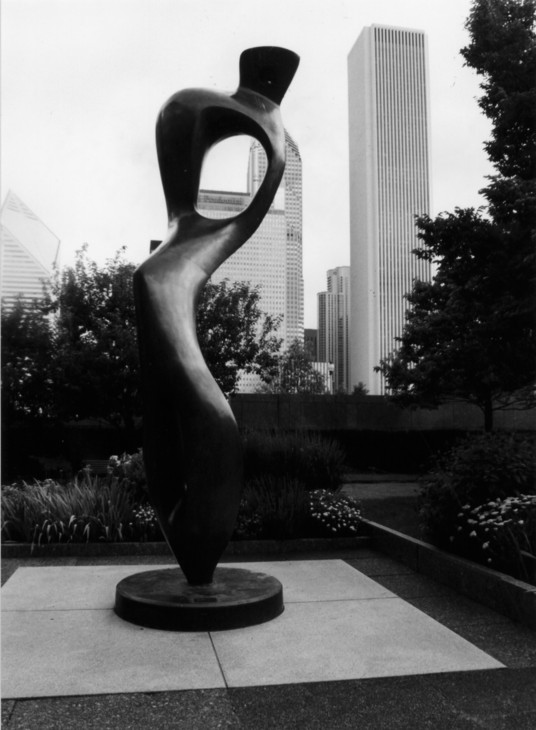

View of Henry Moore's Large Interior Form 1982, at the Art Institute of Chicago 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.6

View of Henry Moore's Large Interior Form 1982, at the Art Institute of Chicago 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Dallas

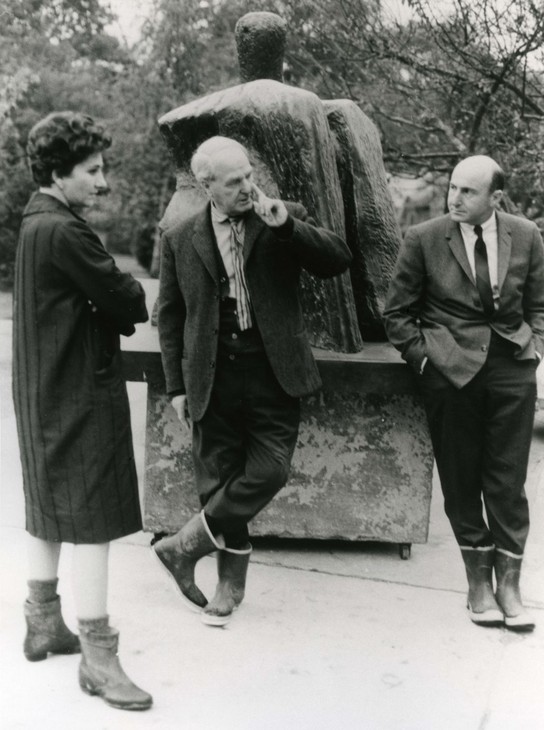

Henry Moore with Raymond and Patsy Nasher, Perry Green, September 1967

Photo: Charles Gimpel

Fig.7

Henry Moore with Raymond and Patsy Nasher, Perry Green, September 1967

Photo: Charles Gimpel

Nasher’s career commenced with the design of residential developments, and grew to encompass the construction of industrial, office and shopping complexes. He also held positions in the public sector, notably in governmental areas of urban and foreign affairs. His core business, however, was in real estate development. He felt that his public service positions had attuned him to art’s social and educational potential and that he could test these ideas within his bank and shopping centre NorthPark in Dallas. Maintaining that art in a commercial context encouraged productivity and enhanced human relationships, he also wished to educate people and to this end he had major sculptures from his collection constantly on display at his NorthPark shopping mall. He understood that many people would encounter art for the first time in such a setting, and that his potential audience was far larger than that which regularly visited museums of art.58 Such philanthropic ambitions did not conflict with business aims, as noted in a press release at the time of the opening of the mall:

as a businessman, Mr. Nasher insists that creative and aesthetic considerations must be compatible with the profit motive ... only through careful business management can society be truly ‘uplifted’ through business support of the arts. ‘If you build something better, and it’s unprofitable, you haven’t advanced human progress. Profitability is a tool for creating a better environment. Practicality and idealism must go together ... We must provide a human environment as well as a physical and commercial environment. If this turns out to be good business, as it has at NorthPark, that’s just the fallout.’59

With Nasher determined that the mall would be unlike any other, he had artworks situated throughout the entire complex, occupying specially designed spaces.60

To coincide with the installation of Three Forms Vertebrae 1978 outside the Dallas City Hall, Nasher, who was also a close friend of City Manager George Schrader, offered to show Moore’s work at NorthPark. An exhibition of sculptures and graphics was organised, to which Dallas Museum of Art loaned their sculpture Two-Piece Reclining Figure, No.3 1961. Punningly titled Dallas Gets Moore, the exhibition was a striking example of co-operation between the artistic, civic and corporate worlds (fig.8). Photographs by David Finn showing Moore’s sculptures on well known public sites around the world, taken from his new book Sculpture and Environment (1977), were included in the exhibition. These not only showed Moore to be an international figure but implied, too, that Dallas ranked among the great cities in the world.

Much was expected of Moore’s Dallas City Hall sculpture, commissioned in part to erase the legacy of the political and national trauma caused when John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza, Dallas, in 1963. The Plaza, site of the city’s foundation in 1841, was emblematic of both a ‘cradle’ and a ‘grave’.61 Perhaps fittingly in relation to the Moore commission at City Hall, Kennedy had established the Advisory Council on the Arts in 1963, using rhetoric that aligned well with the aims of the sponsors of Moore’s sculpture: ‘After the dust of centuries has passed over our cities, we will be remembered not for our victories or defeats in battle, or in politics, but for our contributions to the human spirit ... Art is political in the most profound sense ... as an instrument of understanding ... Art is ... a civic necessity.’62 In 1964 J. Erik Jonsson, president of two of the three organisations that acted as official hosts for the presidential visit and soon afterwards City Mayor, proposed a new programme for the city’s future development, including a new city hall (the original building was known through the world as the site of the murder of Kennedy’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby).63 The Goals for Dallas initiative involved ‘brain-storming by thousands of Dallasites from all sectors to establish common goals.’64 In the resulting publication (1966) it was argued that, ‘The city is our greatest material accomplishment. There is no reason why it should be disorganized, inefficient, unpleasant or ugly. It should, indeed, be our greatest work of art.’65

View of Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.9

View of Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

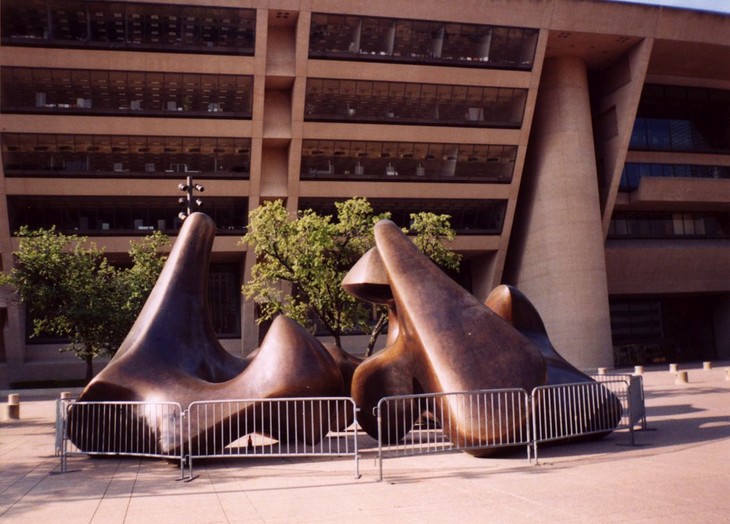

View of downtown Dallas through Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.10

View of downtown Dallas through Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978

Photo: Pauline Rose

Thus much more than a building was at stake when planning began for the City Hall. I.M. Pei was awarded the commission in June 1966. He set out to discover the ‘personality’ of the city and how his building could best represent the people of Dallas, and he also took into consideration the growth in high-rise buildings owned by the banks and corporations that had appeared in downtown Dallas in the 1950s and early 1960s. He believed that the public sector – as represented by his city hall – needed to be symbolically strengthened to offset this concentration of commerce.66 To provide a visual response to the downtown towers, the City Hall was designed to be wider at the top than at the bottom, and thus appear to lean towards the city centre. It is 113 feet high and slopes forward at a 34 degree angle (fig.9). Later the architect would compare this relationship between the city government and Dallas citizens to that between his building and Moore’s sculpture on the plaza (fig.10).67 Pei chose a warm-coloured concrete designed to be in sympathy with the light tones of the dry Dallas region. The building is undoubtedly monumental and impressive, the effect having been enhanced by the clearance of rundown areas that originally fronted the site. These were replaced by a six-acre plaza that is about twice the size of Piazza San Marco in Venice. The building has been described as ‘serious ... one that ... seems to frown under the load of municipal responsibility it contains.’68 By the time of the dedication ceremony on 12 March 1978, however, any criticism of the building’s appearance was subsumed by civic pride.

The new City Hall would provide Moore with one of his most prominent sculptural commissions. Its genesis was complicated although the role played by his supporters is clear: Schrader was familiar with Nasher’s Vertebrae piece, and I.M. Pei had long admired Moore’s work.69 Moore visited Dallas in April 1976, having been invited by the Dallas Museum of Art as a distinguished artist and also, it can be assumed, in preparation for discussions about the commission. During his visit Moore went to the plaza with Schrader and Mrs. Margaret McDermott, a major Dallas art patron.70 She was later contacted by Dallas businessman Fritz Hawn, who wanted to honour his late wife whose favourite artist had been Moore and offered to finance a sculpture. Schrader and Pei were tasked with selecting the work. Pei believed that a work based on Three-Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 would be suitable and he chose as its site an area to the front of the building’s entrance, positioned in relationship with a big circular pool and a group of oak trees.71 The biomorphic and anthropological aspects of the sculpture may be read as an ‘antidote’ to Pei’s uncompromising City Hall design, although the angles of the main forms also echo the leaning profile of the building’s façade. However, this was somewhat fortuitous as the sculpture was an enlargement of the original version.

The City Council played no part in funding the commission but there was still some opposition from that quarter. Councillor William Cothrum believed the work might be too modern for Texans and was critical of the unelected and unrepresentative nature of the City Hall Arts Committee, arguing that a taxi driver should be a member of the committee in order to supply another point of view. The debate descended into farce through public exchanges with the then Mayor, Robert Folsom. Dallas art patrons became dismayed that the city had become a laughing stock. However, Cothrum was quietly ‘stunned’ to discover that his friend Hawn was the donor, and warmed to the commission when Mayor Folsom arranged for him to take Henry and Irina Moore to a Texas Rangers baseball game. ‘I think Henry Moore is a super person’, Cothrum said. ‘Just getting to know him has made me look at his work from a new standpoint.’72

View of Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978 outside Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.11

View of Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978 outside Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Washington D.C.

At the inauguration of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, beside the National Mall at the heart of Washington D.C., President Johnson spoke in 1974 of the new building as showing the city to be a ‘great capital of beauty and learning, no less impressive than its power.’75 Across the Mall I.M. Pei’s 1978 East Building extension to Washington’s National Gallery was also carefully positioned so as to relate to the geometry of the city’s original layout and to make reference to the physical and symbolic importance of its prestigious location. The presence of Henry Moore’s sculptures outside both of these buildings was an unmistakable sign of their acceptability to the political and economic elites in the city.

Henry Moore with Joseph Hirshhorn at Perry Green, November 1962 Photo: Charles Gimpel

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Charles Gimpel

Fig.12

Henry Moore with Joseph Hirshhorn at Perry Green, November 1962 Photo: Charles Gimpel

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Charles Gimpel

View of Henry Moore's Three-Piece Reclining Figure, No.2: Bridge Prop 1963, in Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.13

View of Henry Moore's Three-Piece Reclining Figure, No.2: Bridge Prop 1963, in Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

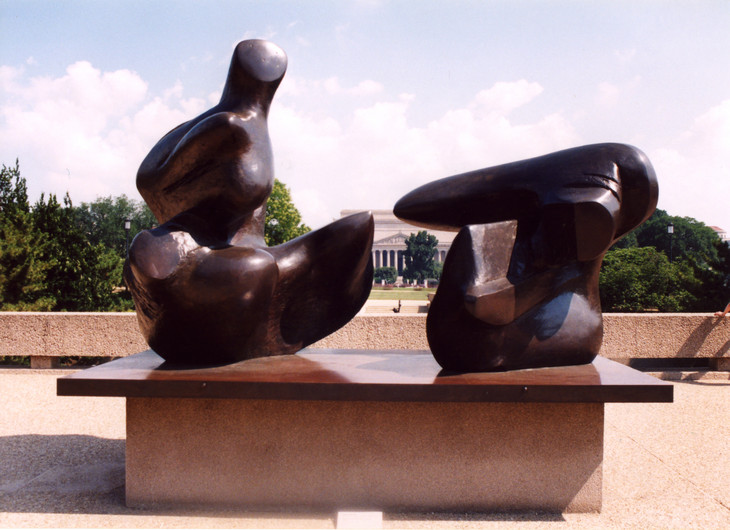

View of Henry Moore's Two-Piece Reclining Figure: Points 1969–70, outside Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C., with the National Gallery of Art in the background 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.14

View of Henry Moore's Two-Piece Reclining Figure: Points 1969–70, outside Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C., with the National Gallery of Art in the background 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

The monumental bronze was placed centrally in front of the Hirshhorn Museum’s entrance and can be seen as providing a visual link to the other side of the Mall, the site of the National Gallery of Art’s West Wing. Close by, I.M. Pei’s East Wing to the National Gallery of Art opened in 1978, four years after the Hirshhorn Museum. At the time it was widely felt that Pei had successfully met the challenge of designing for the awkward triangular site and of relating the new building to its neoclassical West Wing. Director J. Carter Brown believed that Moore’s sculpture could ‘become architecture at civic scale.’79 Writing to the sculptor in 1973, Carter Brown described the importance of Pennsylvania Avenue as ‘the great symbolic way joining the White House with the Capitol and Supreme Court, thus linking the three branches of the Government. It is down this avenue that all State funerals, inaugural parades ... process, and a Presidential Commission is currently working on ways in which the ceremonial character of the avenue can be enhanced.’ He informed Moore that Pei’s new building at the axes of Pennsylvania Avenue and the Mall was positioned at a ‘pivotal point’.80

It seems that initially Moore suggested an enlarged version of an existing sculpture, Spindle Piece 1968, for a site on Pennsylvania Avenue. In May 1974 Moore visited the city and in December informed Carter Brown that he had an idea. He had finished ‘a quite largish and rather massive sculpture’ that was being cast in Berlin, after which he would consider whether it would be right for the National Gallery, although he thought it might be slightly too small.81 ‘The sculptural idea in Spindle Piece is a variation on the “points” theme which I have used in several sculptures ... but ... the points move outward ... suggest(ing) the hub of a wheel. (A rather literary connection might be made as an argument for its appropriateness to Washington ... “the hub of the world”. Sometimes people need a literary reason as a start to look more favourably on sculpture).’82

Spindle Piece arrived in New York on 7 April 1976 and Moore visited the new East Wing on 16 April. The sculpture had not yet arrived in Washington but according to the majority of accounts this was the point at which Moore decided he did not like the Pennsylvania Avenue site. Some say that Moore objected because the work would be out of the sunlight; David Finn, however, said that Moore felt the site ‘would be too busy for a quiet contemplation’ of the work’s forms.83 By the same afternoon arrangements had been made for the sculpture to be diverted from Washington and to continue to the North Carolina Museum of Art, as Gordon Hanes, who was a member of the National Gallery’s Collectors Committee and a trustee at the North Carolina Museum of Art, stepped into the breach and bought the work for the latter museum.84

View of Henry Moore Mirror Knife Edge 1977 by the East Wing, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.15

View of Henry Moore Mirror Knife Edge 1977 by the East Wing, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

View of corner of East Wing, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.16

View of corner of East Wing, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 2003

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Pauline Rose

After some further consideration, Carter Brown and Pei agreed that, if enlarged and if the relative position of the two pieces was reversed and made the ‘mirror image’ of themselves, Moore’s Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5 would be the right sculpture for the museum, and, if sited at the museum’s entrance on 4th Street, people could walk through it on their way into the gallery (fig.15).85

Pei evidently felt able to tell Moore that a reconfigured Knife Edge would be a good choice for the site (and that he did not like Spindle Piece). Speaking to the author in 2003, he said that he chose Knife Edge as it related to the building’s sharp edge (fig.16).86 Up until this point the preferred sculpture for this spot had been Jean Dubuffet’s The Welcome Parade 1974, but this may have been thought perhaps too whimsical a piece for the many congressmen from across the United States who visited Washington and the museum lost its nerve.87 Artistic competitiveness may have played a role here, too: Moore may also have felt that the site in front of the museum entrance was the more prestigious site. The work was installed in May 1978.

***

As this essay has attempted to show through reference to four American cities, commissions gave Moore a public presence in the US that was unprecedented for a foreign living sculptor. In New York the commissions signalled Moore’s growing status within the art world; in Chicago they allowed Moore to be part of that city’s history of important public sculpture; in Dallas Moore’s work became part of the story of the city’s recovery from national trauma; and in Washington D.C. the siting of Moore’s bronzes outside both the Hirshhorn and the National Gallery of Art marked the zenith of his official acceptance and admiration in the US. Interconnections between friends, patrons, businessmen, politicians and museum personnel worked to facilitate these placements and furnished much of the momentum for Moore’s career.

Moore appears to have been attracted to American openness, enthusiasm and entrepreneurship and, in turn, his personality seems to have played an important role in his success in the US. Americans time and again commented on Moore’s friendly nature, his down-to-earth way of talking about his work, the fact that he was the opposite of a difficult, eccentric and troublesome contemporary artist. Those who visited him at his home and studios at Perry Green – and so many patrons, architects and businessmen did – responded favourably to seeing Moore embedded in a particularly lovely part of the English countryside, with all the somewhat romanticised connotations that inevitably conveyed.

American patrons were among Moore’s staunchest allies, and as the biographer Roger Berthoud has commented, this support went a long way to buoy the sculptor’s reputation when it was assailed at home. In the post-war years, Berthoud writes, Moore was

between a number of reputations ... the reactions of the broad public, conscious mainly perhaps of his international fame; and the growing admiration of American collectors and business men, for whom the sculptor was becoming the acceptable face of modern art. This last group was to be a source of comfort in the coming years as the assaults of the younger generation reached their maximum intensity.88

There were of course risks involved in the promotion of Moore everywhere, even as a foreign star, and Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., was well aware that the commission of a major Moore bronze in the 1970s risked being seen as a ‘cliché’. But the alternatives – in this case the more light-hearted work of Jean Dubuffet – felt risky for a site of major national importance. And, as he noted in an interview in 1994, ‘Henry Moore was one of the toughest bargainers you’ll ever run into ... He was not going to be playing second fiddle to anybody’.89

Notes

A.M. Frankfurter, ‘Henry Moore: America’s First View of England’s First Sculptor’, Art News, December 1946, pp.26–9.

Hilton Kramer, ‘Art: Civic-Minded People’s Choice’, New York Times, 4 October 1967, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

See Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, International Style: Architecture Since 1922, New York 1932, and John Dewey, Art As Experience, New York 1934.

Charles Landry and Lesley Greene, The Art of Regeneration: Urban Renewal through Cultural Activity, London 1996, p.22.

William S. Lieberman, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Collection: Masterpieces of Modern Art, New York 1981, p.24.

David Rockefeller, ‘Culture and the Corporation’, founding address for the Business Committee for the Arts, Inc., delivered at 50th Anniversary Conference, National Industrial Conference Board, New York, 20 September 1966.

Livingstone L. Biddle, Our Government and the Arts: A Perspective from the Inside, New York 1988, p.239. John D. Rockefeller III controlled the project, which was characterised as partly echoing his father’s work at the Rockefeller Center (oral history interview by Sharon Zane with Robert Blum, New York 1990, p.40, Lincoln Center Archives, New York). Key figures at New York’s MoMA were also involved, including René D’Harnoncourt and Alfred Barr who also advised John D. Rockefeller III. The choice of art for the Center could thus be seen as representative of a MoMA ‘aesthetic’ (oral history interview by Sharon Zane with Philip Johnson, New York, 4 August 1990, p.88, Lincoln Center Archives, New York.)

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York 1964 (Max Abramovitz Papers, 1926–1995, Folder: 1990.007, Lincoln Center correspondence, Avery Architecture and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Oral history interview by Sharon Zane with Kevin Roche, New York, 17 August 1995, p.12, Lincoln Center Archives, New York.

Roger Berthoud interview with Gordon Bunshaft, New York, 30 November 1983, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Interview by Zane with Blum, p.50. The sculptor on the Art Commission was Eleanor Platt, a member of the National Sculpture Society (see Harriet F. Senie, ‘Implicit Intimacy: The Persistent Appeal of Henry Moore’s Public Art’, in Dorothy M. Kosinski, Henry Moore: Sculpting the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, New Haven and London 2001, p.282).

Oral history interview by Sharon Zane with Frank Stanton, New York, 18 January 1991, p.36, Lincoln Center Archives, New York.

Roger Berthoud interview with George Ablah, New York, 13 November 1985, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Letter from Joseph Bresnan, Director of Planning and Preservation to Melvin Dodge, Director of Department of Recreation and Parks, 28 August 1984, New York Parks Department Archives.

Larry Sutton, ‘Two Park Sculpture with City’, Daily News, 28 March 1985, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

New York Art Commission resolution for removal of Moore’s Two-Piece Reclining Figure: Points, 7 April 1989, New York Parks Department Archives.

Inter Ocean, 15 April 1905, quoted in James L. Riedy, Chicago Sculpture, Chicago and London 1981, p.9.

Ira J. Bach & Mary Lackritz Gray, A Guide to Chicago’s Public Sculpture, Chicago and London 1983, p.xvii.

Letter from Robin Pearce, Director, Fine Arts Program, University of Chicago, to Henry Moore, 1 February 1960, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

A CBC film’s first showing in the United States was at the University and the Art Institute. There was also a screening at the Institute of a BBC Face to Face interview, shown for the first time in the United States.

Copied extract of Minutes of Fermi Memorial Planning Committee, University of Chicago, 15 July 1965, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Press release from Joseph Brisben, Office of Public Relations, University of Chicago, 26 November 1967, Atomic Energy Anniversary Celebrations 1967, File 1, Special Collections, University of Chicago.

Franz Schulze, ‘Tell Us, Sir (sic) Henry’, Chicago Daily News, 2 December 1967, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Arthur J. Snider, ‘Fermi Statue Creates Furor (sic) at University of Chicago’, Chicago Daily News, 16 July 1965, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Larry Wolters, ‘Both Life and Death – Shaped in Bronze’, Chicago Tribune Magazine, section 7, 28 November 1965, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Andrew Graham-Dixon, ‘The Catastrophe Culture’, Independent, 3 February 1987, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Devon Pyle-Vowles, Collections Manager, Adler Planetarium, Chicago, letter to author, 14 August 2003.

‘Proposal to the Committee on The Ferguson Fund of The Art Institute of Chicago from The Adler Planetarium’, undated, enclosed with letter from Kenneth Nebenzahl to James Wood, 22 May 1979, Adler Planetarium Archives, Chicago.

Christopher Lyon, ‘Henry Moore’s Offspring Finds a Secure Home at First National’, Chicago Sun Times, 8 May 1983, The Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Neil Harris, Cultural Excursions: Marketing Appetites and Cultural Tastes in Modern America, Chicago and London 1990, p.293.

Charles M. Edwards, ‘Art Can be Beautiful and Make Your Leasing Easier, Too’, Lobby Art and Plazas, Skyscraper Management, vol.58, no.9, Building Owners and Managers Association International, September 1973, p.7.

Press release, ‘Two Henry Moore Sculptures Come to Chicago’, 6 May 1983. Art Institute of Chicago Archives.

Masterworks of Modern Sculpture: The Nasher Collection, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1996, p.32.

David Finn and Judith Jedlicka, The Art of Leadership: Building Business-Arts Alliances, New York, London and Paris 1998, p.135.

Darwin Payne, Big D: Triumphs and Troubles of an American Supercity in the Twentieth Century, Dallas 1994, p.330.

Bonnie Lovell, interview with George Schrader, Addison, Texas, 19 June 2002, Dallas Public Library: Texas/Dallas History and Archives.

Bonnie Lovell, interview with I. M. Pei, New York, 1 August 2002, Dallas Public Library: Texas/Dallas History and Archives.

Henry Tatum, ‘Cothrum Shapes New Respect for Moore, his Work’, Dallas Morning News, 6 December 1978, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

The sculpture is approximately forty feet long and Moore intended that a viewer should be able to move through its forms, but vandalism led the work to be fenced off.

John Neville, ‘Art: Major Henry Moore Sculpture Acquired by DMFA’, Dallas Morning News, 16 January 1965, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Roger Berthoud, interview with Olga Hirshhorn, 11 November 1985, Henry Moore Foundation Archive. Hirshhorn sent a cheque for $30,000 to the Tate Gallery in honour of Moore’s seventieth birthday.

David Finn, ‘Looking at Henry Moore’s “Mirror Knife Edge”’, Roll Call, Washington D.C., 14 December 1989, The Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Memorandum from Jerry Mallick, Registrar’s Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., to the file, 19 April 1976. RG 11c, Box 8. File E. B. Art – Moore. Spindle Piece [c.1976 –], National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

It is unclear as to what involvement Moore had with the change of sculpture. It seems that the change occurred when the site was moved to the front entrance. In an interview with the author Pei said he recommended Knife Edge and suggested that perhaps Spindle Piece had originally been selected by Carter Brown and the committee (author’s interview with I. M. Pei, New York, 1 August 2003).

Acknowledgements

This essay draws on material in Pauline Rose, Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, London 2014.

Dr Pauline Rose is Professor of Art History at the Arts University Bournemouth.

How to cite

Pauline Rose, ‘Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www