Henry Moore and ‘Sculpture in the Open Air’: Exhibitions in London’s Parks

Jennifer Powell

Moore often talked of his fondness of seeing his sculptures in natural settings. This essay explores a series of open air exhibitions of sculpture held in London in the post-war decades, and traces their impact on the public’s understanding of his work.

Between 1948 and the mid-1970s the parks of the London County Council (from 1965 the Greater London Council) were frequently transformed during the summer months into ‘Open-Air Sculpture Galleries’.1 This essay focuses on the first seven exhibitions that were staged as a regular triennial series between 1948 and 1966 in Battersea and Holland parks.2 Henry Moore was a ubiquitous presence in these exhibitions: he sat on the organising committee of the first; his works were included in every show and featured prominently in the accompanying catalogues and marketing initiatives; and critical responses to the open air displays frequently singled out Moore’s works for comment. Drawing upon archival sources, including meeting reports and press reviews, this essay interrogates the role that the Sculpture in the Open Air exhibitions played in shaping public perceptions of Moore after the Second World War.

The open air exhibitions

Patricia Strauss, a newly elected Labour committee member and Chair of the LCC Parks Committee, initiated the first exhibition. She was clear about her wish to facilitate increased opportunities for the public to see sculpture, which, she suggested in her 1948 catalogue foreword, ‘was a somewhat neglected art in England’.3 In an early letter in which Strauss first mooted her idea, she explained that the exhibition should not be limited to the work of Royal Academicians but should include sculpture by Moore, Dora Gordine and Jacob Epstein in order to ‘show our public and the world the trends of modern sculpture’.4 She continued: ‘Indeed, I would like it to frankly be an exhibition of Modern Sculpture; and if the discussion aroused is controversial, so much the better’.5 Strauss’s ambition for the project stretched far beyond her local council authority, and her focus on Moore and Gordine certainly reflected her personal tastes as a collector (by 1951 she had personally acquired works by both artists).6 A former professional artist’s model and journalist, Strauss was the wife of George Strauss, a wealthy pre-war London County Council (LCC) Labour representative and Minister of Transport and Supply after the war.7 Her call for the exhibitions to fuel debates about modern sculpture was a bold one, since it was directed at members of the Parks Committee, few of whom shared her knowledge of, or passion for, sculpture.

In the summer of 1948 Britain was still at the beginning of a long process of reconstruction after the Second World War. The Council for Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) was replaced by the Arts Council in January 1945 and the new Labour government boosted the latter’s spending grant by £50,000 to £235,000 to help develop the arts in Britain. The Labour-led LCC had already taken steps to exploit a new central government act that enabled local authorities to spend up to six pence per pound of their General Rate Fund on cultural activities and urged local authorities to provide ‘entertainments and amusements of all kinds’ in their open spaces.8 In response, local authorities in London had increased their open-air offer by staging music concerts, ballet, theatre and circus performances, mobile cinema screenings, roller skating events, and swimming galas. When the Arts Council suggested that the first open air sculpture exhibition could be staged in a London square, where public access might be more easily controlled, the LCC objected: Strauss and her committee saw the exhibitions as a unique opportunity to promote the use of the parks within the city.9 As art historian Robert Burstow has explored in an essay of 2006, the series also fulfilled Labour’s socialist initiative to develop and support cultured leisure activity that was accessible to all, through, what he described as, the ‘cult of the open air’.10

Art historians Dawn Pereira and Margaret Garlake have discussed the LCC’s extensive arts commissioning programme and, through this, its support for Moore.11 From 1956 the Council devoted £20,000 a year towards the purchase, or commission, of artworks. It described its commitment as ‘a source of the greatest encouragement in the field of patronage, where many local authorities have yet to discover their responsibilities’.12 As the first municipally-funded and government-backed set of temporary displays to present sculpture in public parks in Britain, the Sculpture in the Open Air series inspired further initiatives in Britain and abroad. These included the Arts Council’s own British Contemporary Sculpture touring exhibitions, which offered regional cities opportunities to display sculpture outdoors from 1956 (and included works by Moore).13 The Arts Council credited the LCC shows as their model,14 and it was heavily involved in the LCC open air exhibitions from the outset: it committed some additional funding to the series and representatives sat on the exhibition committees. In its First Annual Report the Arts Council pledged to ‘make London a great artistic metropolis, a place to visit and to wonder at’, while noting at the same time that ‘for this purpose London today is half a ruin’.15 The LCC exhibitions helped serve the Arts Council’s wider aims to revive the visual arts in Britain and affirm the country’s cultural strength.

The seven open air exhibitions that form the focus of this essay were not staged as a series and did not follow a particular thematic plan. Membership of the organising and selection committees was fluid, and Moore only sat on the first. The committees were typically composed of a Chair, a small number of LCC Parks Committee members (who did not select the works) and Arts Council representatives. Alongside this core body were invited artists and specialists: for example, John Rothenstein (Director of the Tate Gallery), Kenneth Clark (former Director of the National Gallery) and Eric Maclagan (Chair of the Fine Arts Committee of the British Council), all sat on the 1948 committee. This organisational structure changed in 1954 when a new ‘advisory committee’ opened its doors to representatives from a greater number of cultural organisations including the Royal Academy, Royal Society of British Sculptors and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, as well as nominated sculptors. A complex voting system ensued in which artists were variously asked to submit named works that had been identified by the committee, or works of their choosing, for consideration. Margaret Garlake has explored in detail ‘the war of taste’ that erupted between members of these arts organisations who often approached the selection of artists from highly personal and often oppositional positions, broadly supporting figuration or abstraction (such distinctions were, of course, far more complex and subtle than this).16 Only the final showing of all-British and contemporary sculpture was selected and curated largely autonomously by the art historian and curator Alan Bowness.

The first Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture (1948) included two of Moore’s carved stone sculptures, Recumbent Figure 1939 (Tate N05387) and Three Standing Figures 1947, which was lent by the artist (figs.1 and 2). The latter had already been made, with the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in mind, but Moore was pleased with the work’s siting on a slight rise. He said he had been trying to express some of the feeling of community that he had expressed in his Shelter Drawings:

The slight rise over-looking an open stretch of park and the background of trees emphasised their outward and upward stare into space. They are the expression in sculpture of the group feeling that I was concerned with in the shelter drawings, and although the problem of relating separate sculptural units was not new to me, my previous experience of the problem had involved more abstract forms; the bringing together of these three figures involved the creation of a unified human mood. The pervading theme of the shelter drawings was the group sense of communion in the three figures ... I wanted to overlay it with the sense of release, and create figures conscious of being in the open air, they have a lifted gaze, for scanning distances.17

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure 1938

Green Hornton stone

object: 889 x 1327 x 737 mm, 520 kg

Tate N05387

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1947

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1947

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

As well as sitting on the selection committee, Moore advised on the arrangement of works. He was tasked, along with fellow artist committee members Frank Dobson and Charles Wheeler, Maclagan, Rothenstein and others, to consider ‘the effect of undulation of the site on the pedestals, height of pedestals, arrangement of pieces’.18 The choice of Moore’s works may have been made by the artist himself although, in the case of Recumbent Figure, its selection satisfied others, too, as it was the first work by Moore to be acquired by the Tate Gallery under Rothenstein’s Directorship and Clark had played a key role in brokering its gift to the gallery through the Contemporary Art Society (CAS).

At the time of the first open air exhibition Moore was becoming recognised as an artist who could contribute a great deal to the regeneration of the arts in Britain.19 He was at the end of his first term as a Trustee of the Tate Gallery (1941–8), and was soon to start a second term. He also served on numerous other committees including the Arts Council’s Art Panel, the Institute of Contemporary Arts (founded 1948), and smaller independent organisations such as the Anglo French Art Centre, London (1946–51). Moore’s works were becoming increasingly visible in public collections and exhibitions: his popular wartime Shelter Drawings had been placed in public galleries by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee. Eight were given to the Tate Gallery, which, in addition to Recumbent Figure, had acquired four of Moore’s bronze maquettes for his Northampton Madonna and Child and three maquettes for Family Group in 1945 (a full-size bronze cast of the latter was purchased in 1950). In the summer of 1948 Moore’s work was presented in the national pavilion, curated by Rothenstein, at the Venice Biennale, alongside the works of the nineteenth-century master J.M.W. Turner; and he won there the international sculpture prize. His sculptures were also being exhibited internationally: Moore’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1946 had met with critical acclaim,20 and an extensive touring programme of his work, facilitated by the British Council, was underway and had reached Australia in 1947. Moore was invited to participate in all of the open air exhibitions and committee reports show that he often received a high number of votes. This suggests not only that his work was familiar to, and liked by, the diverse range of people whom sat on the committees, but that many were also conscious of Moore’s growing public exposure and the value that this might afford to the exhibitions’ success.21

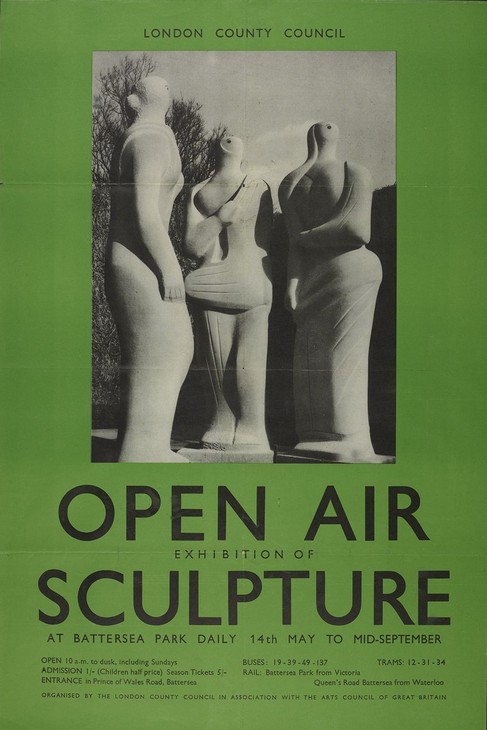

Poster advertising the 1948 Sculpture in the Open Air exhibition, featuring Moore's Three Standing Figures 1947

London Metropolitan Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Poster advertising the 1948 Sculpture in the Open Air exhibition, featuring Moore's Three Standing Figures 1947

London Metropolitan Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Committee reports relating to the first open air exhibition show that despite Moore’s inclusion, members of the LCC committee were concerned about what they identified as a lack in quality, and quantity, of British sculpture available to mount a successful show.26 In order to address these worries it was agreed that the exhibition should include international artists. ‘It is essential that the success of the first exhibition shall be put beyond doubt’, the report of the July 1947 committee reads. ‘It should therefore be international in character, including the work now in Great Britain executed by British or foreign sculptors of the past fifty years and perhaps, as the exhibition is publicised, some pieces from abroad.’27

Perhaps the Travel Association’s objections to the Recumbent Figure for their poster image echoed the committees wider concerns about the international appeal of British sculpture in 1948. In the end only four works came from France and all of these were lent by the artists (Henri Laurens, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Matisse, and Ossip Zadkine); however, August Maillol’s Woman with Necklace c.1918–8,28 lent by the Tate Gallery, was illustrated on the cover of the exhibition catalogue and immediately signaled the exhibition’s international reach to an informed reader. Of the forty-three works included in the exhibition, twenty-nine were loaned by the Tate Gallery. This reduced transport costs and also ensured a strong presentation in the first exhibition of the nation’s British and international sculpture collections during a time of national reconstruction.

The 1951 Sculpture: An Open Air Exhibition did not officially form part of the concurrent Festival of Britain programme. Perhaps in an effort to make the exhibition’s offer distinct from the celebration of Britain’s national achievements in the arts, science and industry, the committee’s discussions centered on securing about twenty ‘foreign’ pieces from at least six countries to further broader the exhibition’s international character.29 Loans were negotiated from numerous institutions in France and from MoMA in New York. Moore lent his Standing Figure 1950, a work that formed part of his Double Standing Figure 1950, which was prominently displayed outside the national pavilion at the Venice Biennale in the following year.

The 1954 and 1957 exhibitions were staged in Holland Park. The first was constrained by the need to reduce costs, which necessitated a heavy weighting towards artists working in Britain. Gilbert Ledward, President of the Royal Society of British Sculptors, led the choice of theme for the second, which displayed exclusively British works from 1850 to 1950.

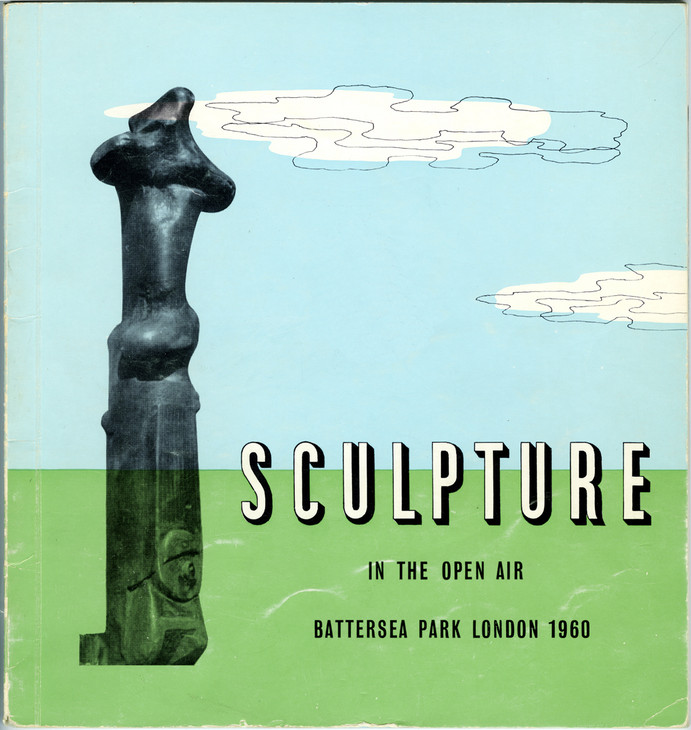

Cover of the 1960 exhibition catalogue of Sculpture in the Open Air showing Moore's Glenkiln Cross 1955–6

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Fig.4

Cover of the 1960 exhibition catalogue of Sculpture in the Open Air showing Moore's Glenkiln Cross 1955–6

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Photograph showing Reg Butler’s The Bride 1954–61 and William Turnbull’s Aphrodite 1958, with Moore’s Standing Figure (Knife-Edge) 1961 at the top of the hill in the British section of Sculpture in the Open Air, Battersea Park, 1963

London Metropolitan Archives

Photograph showing Reg Butler's The Bride 1954–61 and William Turnbull's Aphrodite 1958, with Moore's Standing Figure (Knife-Edge) 1961 at the top of the hill in the British section of Sculpture in the Open Air, Battersea Park, 1963

London Metropolitan Archives

Fig.5

Photograph showing Reg Butler's The Bride 1954–61 and William Turnbull's Aphrodite 1958, with Moore's Standing Figure (Knife-Edge) 1961 at the top of the hill in the British section of Sculpture in the Open Air, Battersea Park, 1963

London Metropolitan Archives

Moore’s Three Point Vertebrate was the catalogue cover image for the 1966 exhibition, which showcased works by British artists and aimed to display more contemporary work than in any previous exhibition. Moore also exhibited his Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.4 1963–4 and Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4. The cover image Three Point Vertebrate was the most abstract piece that Moore had shown at the LCC shows to date, but the rounded bronze masses retained their characteristic surface textures and evidence of the sculptor’s marks. For some of the younger sculptors in the exhibition, Moore’s work was a point of departure, something to be responded to and reacted against: they used welded, rather than cast, metal to crate abstract constructions that were also sometimes brightly coloured. In striking contrast to Strauss’s comment in 1948 that sculpture in England was a neglected art form, the art historian and curator Alan Bowness announced in his catalogue introduction that ‘we are witnessing in this country, here and now, one of the great epochs in the history of the art [of sculpture]’ and attributed this largely to Moore’s example.32 Some reviewers remained unconvinced. The Times critic, for example, noted that the previous exhibition had made a strong case for recognising the existence of a British national school but that the absence of foreign work in the present show ‘might be taken to symbolise the belief, which has been rapidly growing since the last Battersea show three years ago, in the supremacy as English sculpture’. The reviewer continued, ‘This wild claim can hardly be taken seriously in the context of the present exhibition which is decidedly patchy.’33

An understanding of the arrangement of the sculptures in Battersea and Holland parks can be gained through studying contemporary photographs (held in the London Metropolitan Archives), film footage (a number of contemporary British Pathé films were made of the exhibitions), visitor maps that were included in the majority of the exhibition catalogues, and press reviews. Both parks offered generous expanses of largely flat lawns and open parkland, with some areas of undulation and hilly rises (particularly in Battersea), and more enclosed pockets of the landscape lined with trees and shrubbery. An area of Battersea park, adjacent to the lake with mature trees and generous planting, is likely to have been the setting for all of the exhibitions held there.34 The Holland park shows of 1954 and 1957 were held in roughly similar areas of the park, though the latter also made use of the restored orangery: the description of yucca and bamboo plants in the 1954 catalogue evoked a rather exotic setting for some of the sculptures.35 In 1954 Moore’s Draped Reclining Figure 1952 was installed in generous space against the tree line, and in 1957 his Warrior with Shield 1953–4 was grouped with the work of younger sculptors, opposite his former assistant Bernard Meadows and in line with works by Reg Butler and Lynn Chadwick.36 In Battersea in 1960 Moore’s Glenkiln Cross was sited at the furthest end of the park from its intended entrance: although critical of the exhibition as a whole, critic Robert Melville described how the work ‘taller than the rest, literally rose above the confusion’ in a full page spread in Architectural Review.37 In 1963 visitors to the Battersea show encountered Moore’s works almost immediately at the entrance, and in 1966 the artist’s three bronzes sat in a central position in the park. Moore’s aforementioned recollection about the positioning of his three standing figures on a rise in Battersea Park in 1948, which he undoubtedly partially engineered as a member of the display team, seems to have been carried through to some of the later shows. In 1963 and in 1966 Standing Figure Knife Edge and Two-Piece Reclining Figure No 4 1963–4 were both sited respectively on high ground. A number of press articles provide further clues about the impact of the display of Moore’s sculptures upon the visitor and describe the works’ prominent positioning in the parks. Of the 1948 exhibition (for which no visitor map exists), for example, Edith Hoffman commented in the Burlington Magazine that the exhibition was, ‘literally speaking’, arranged around Moore’s Three Standing Figures.38 As noted previously, the Times described how Moore was ‘predictably’ at the top of the slope and the works by other British artists were ‘in tiers below him’ in 1963.39 In this exhibition the separation of national schools was physically embodied in the display of sculpture in different areas of the park. Moore was positioned at the helm of the British ‘school’, which was largely clustered around the entrance in a curatorial strategy that sought to highlight Britain’s cultural strength.40

Engaging the public

The LLC exhibitions were not the sole initiative in these years concerned with bringing sculpture to the notice of a broad public. From 1946 to 1959 the Arts Council staged a series of four Sculpture in the Home exhibitions, which aimed ‘to encourage an appreciation of an art which is less widely recognised than painting as being suitable for decoration of the home’.41 These shows, which included works by Moore, toured the length and breath of the country, reaching Southampton, Cambridge, Cardiff, Newcastle, Glasgow and Aberdeen. The open air exhibitions, however, were marked by an informality that aimed to reduce the physical and sometimes psychological barriers surrounding the display of artworks in museums. The sculptures were on plinths but did not have barriers. A lecturer noted that the ‘informal atmosphere made people far less self conscious than they are as a rule in a gallery’ (fig.6).42 This point was echoed in a documentary made by John Read about Moore called A Sculptor’s Landscape (first broadcast on 29 June 1958). It featured works in the Battersea exhibition and showed visitors touching the sculptures (the narrator states that ‘in this setting, sculpture is seen with greater freedom than in the formal and confined atmosphere of the museum’).43 Probably taken for press use, photographs in the London Metropolitan Archives also show members of the public touching, leaning or sitting on sculptures in various LCC shows. The exhibitions were accompanied by series of events that aimed to encourage access to, and understanding of, the sculptures on display. Daily guided visits for adults (organised by the Arts Council) and children, along with practical art-making classes, were offered for the first show, and the LCC instructed Eric Newton to ensure that his catalogue essay would ‘help the plain man to understand what to look for in a piece of sculpture’.44 Battersea Public Libraries encouraged visitors to borrow books on art through a pamphlet produced for the 1948 exhibition that featured a cartoon of a perplexed spectator viewing a Moore-inspired sculpture in a park.45

A guided group in front of Henry Moore's Three Standing Figures at the Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture in Battersea Park, London 1948

London Metropolitan Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

A guided group in front of Henry Moore's Three Standing Figures at the Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture in Battersea Park, London 1948

London Metropolitan Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is difficult to accurately measure the success of the LCC’s drive to democratise access to sculpture through the open air exhibitions. The astonishing visitor numbers recorded for the first exhibition – over 150,000 (with over 2000 postcards being sold within six weeks despite their late release) – fuelled the Council’s commitment to the second. However, visitor numbers were not sustained and although strong again in 1957 and 1960 (with around 72,000 and 70,000 respectively), they steadily fell to a low in 1963 with a disappointing figure of 38,561 (24,000 had visited in the first week alone of the 1948 exhibition). The innovative experience of the open air stage had perhaps begun to lose its appeal, although numbers recovered again in 1966 to about 60,000 for the celebration of contemporary British sculpture. Little data exists about the demographics of the visitors, although it should be noted that entry fees were charged for each show, usually at one shilling for adults, and the glossy catalogue typically cost 5 shillings or half a crown. In 1954 a high number of students and children was recorded, and a report from 1960 noted that the majority of visitors were upper-middle class Londoners of a relatively young age who could be described as culturally active.46 Guide lecturer Matvyn Wright recorded her view that the 1948 exhibition attracted ‘a large public whose intelligence is on average, much higher than in the provinces’.47

Press coverage, however, was always extensive, involving not only newspapers but also magazines, art journals, and the radio and television. As art historian Felice McDowell has explored, Moore’s Three Standing Figures in the 1948 show featured as the backdrop to fashion spreads in the U.K. editions of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue magazines (the latter included a photograph of Moore himself).48 The artist’s work continued to be used in the fashion pages into the 1960s. In 1961, for example, Three Standing Figures appeared in Queen magazine’s feature ‘Exit Lines the Bathing Suit-style Dresses’, in which the two models stood on and leant against the sculpture.49 Although the recurrent use of Moore’s work as a backdrop for high fashion shoots might be taken as evidence of its familiarity and suitability for wider public consumption, these glossy fashion magazines were targeting middle-class and upper-class audiences, and the fashions they contained were often inspired by the high-couture of Parisian fashion houses. The linkage with Moore signaled a British context for the British fashion houses’ new lines, but in practice these were attainable only by a privileged few.

The responses of critics to the early exhibitions were broadly positive, although they frequently focused more on the novelty of the setting than upon analysis of the sculpture on display. The Illustrated London News, which included an image of Three Standing Figures and other works, described the open air as the ‘ideal setting’ for sculpture in 1948 and again in 1951.50 A critic for the Times concurred in 1948 that parkland was the ‘right place’ for the works and commented that their setting made them more approachable.51 In his 1951 review for the New Statesman and Nation Benedict Nicolson agreed, saying that ‘this is the way sculpture ought to be seen, from a flattering distance on a spring day, accompanied by a song of birds’.52 Such responses were at odds with the LCC’s drive to encourage understanding of sculptural practice, encouraging people to expect an enjoyable social experience in which they might walk through the parks and, as it were, stumble upon works of art on a sunny day.

The 1966 exhibition, which featured sculptures made with steel and coloured metals, led some critics to question the suitability of including such works in a landscape-based show. Bruce Laughton commented that ‘in general it is the older generation of sculptors who benefit most from a landscape environment. The younger generation, still dominated by Caro, seem to be developing an idiom entirely urban in character, which needs a special artifice in presentation’.53 Perhaps anticipating such comments Bowness had sited some such works on areas of paving and had put up screens for some smaller works. But in his introduction to the 1966 exhibition he noted that the open air shows had helped to create a way of looking at, and appreciating, the work of Moore and his generation: ‘the revolutionaries of the 1948 exhibition, Moore and Hepworth, now appear as the old masters of the 1966 one. They alone, with another pioneer, McWilliam, have shown every time. We can appreciate how they have dominated these exhibitions, which have in turn provided the perfect setting for their sculptures. In a way they [the exhibitions] created their aesthetic.’54

Moore himself actively promoted the associations between his work and the landscape in the many interviews he gave in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1951 Moore was recorded as saying, ‘Sculpture is an art of the open air. Daylight, sunlight is necessary to it, and for me its best setting and complement is nature. I would rather have a piece of my sculpture in a landscape, almost any landscape, than in, or on, the most beautiful building I know’.55 Documentaries about his work by John Read played an important role, too. His 1951 film showed Three Standing Figures in its permanent position in Battersea Park and Reclining Figure 1951 against the open parkland of Moore’s home in Perry Green. In 1958 another film showed Moore’s newly built studio that allowed him to position his large pieces outdoors more easily: the narrator quotes Moore as saying that ‘work meant to be looked at out of doors cannot be entirely made indoors’.56 The Sculpture in the Open Air exhibitions helped to construct and make public the connections between the aesthetic of Moore’s sculpture and the landscape, albeit semi-urbanised parkland. In 1956 architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner had said that, aside from Moore, ‘the English are not a sculptural Nation’ in his book The Englishness of English Art (1956).57 Pevsner, however, went on to emphasise Moore’s links to nature. Reviews and catalogue writers such as James and Read, were particularly positive about the placement of Moore’s works in open air parkland, and this British landscape setting provided a fertile ground on which to stress the nations achievements in sculpture and their particular debt to Moore.

The Sculpture in the Open Air exhibitions of 1948 to 1966 enabled over half a million visitors (approximately 567,000) to see Moore’s large-scale sculptures and works by his contemporaries working in Britain, Europe (particularly France) and America. The relaxed and social experience that the parks provided alongside the extensive accompanying events programmes, offered a broad public an alternative way of viewing and engaging with sculpture (although as previously noted it is difficult to fully access how successful the exhibitions were in widening access and the demographic its visitors). Through the selection of Moore’s work, the prominent positioning within the parks, images on posters, catalogues and in the press, and through catalogue essays, the LCC/GLC exhibitions demonstrated their unwavering support for Moore and increased his public exposure in London. The Arts Council’s involvement in the open air exhibitions and their subsequent drive to extend the reach of this initiative across towns in Britain, encouraged the circulation of large-scale sculpture around the country. The LCC’S model also encouraged international interest, which further increased the outdoor platforms for the display of Moore’s works; for example, the organisers of the 1959 open air exhibition in Middelheim, Antwerp, wrote to the LCC to seek advice about the organisation of their show which focused on British sculpture and included sixteen works by Moore.58 The wider impact of these exhibitions on the growing reputation of British sculpture and the process of national rebuilding, is arguably evidenced in the progressing confidence of the committees’ discussions and selections for the later exhibitions in which British sculpture was either confidently set against that of France or America, or celebrated independently in 1966. Following Alan Bowness’s self-proclaimed triumphant all-British contemporary show in 1966,59 however, the GLC came under the control of the Conservative Party and with a new political agenda at the heart of the council there were no further open-air exhibitions until the mid-1970s; arguably, the London party’s identification of this scheme as a Labour initiative, coupled with the fading novelty of open air exhibitions, led to the cessation of the Council’s regular commitment to the scheme.

Moore was sensitive to the risks involved in open air exhibitions and to the repeated use by critics and reporters of his 1951 statement in which he spoke of his love of seeing sculpture in the landscape.60 In 1962 Moore suggested that these open air stages allowed the sculptor to ‘go out into the world to meet a larger public and make new friends’ but there was also a ‘danger that the people will confuse their love of flowers, gardens, and visit to the park with an interest in sculpture’.61 At a time when he was being regularly commissioned to make sculptures to be positioned in front of landmark buildings and in urban spaces internationally it was necessary for Moore to advocate more than one ‘ideal’ environment for his public sculptures. With the exception of Recumbent Figure 1939 and Warrior with Shield 1953–4, models or closely related versions of all of the sculptures that Moore displayed at Battersea and Holland parks were subsequently permanently sited outdoors. As some pieces were placed in urban spaces, and some had been on display in parkland settings before their inclusion in the open air shows, it would be inaccurate to suggest that their display in the London parks led directly to their placement in comparable settings. It is fitting, though, that Three Standing Figures – the poster image for the landmark 1948 Sculpture in the Open Air exhibition – was permanently sited in one of the council parks: it stands today in Battersea Park as a reminder of an innovative set of exhibitions that propelled Moore’s sculptures further into public consciousness after the Second World War.

Notes

Anon., ‘Battersea Park as an Open-Air Sculpture Gallery: Statues with a Background of Summer Foliage’, Illustrated London News, 22 May 1948, pp.588–9.

The Greater London Council (GLC) organised a number of additional open air sculpture exhibitions in the 1970s. These included The Illustrated London News Presents an Exhibition of Figurative Sculpture in Holland Park, May–July 1975 (which did not feature work by Moore), and A Silver Jubilee Exhibition of Contemporary British Sculpture, Battersea Park London, June–September 1977 (Moore served on the selection committee).

Patricia Strauss, ‘Foreword’, Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London, May–September 1948, p.3.

Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the Public Park: A Socialist Experiment in Open-Air Cultured Leisure’, in Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture and the Garden, Aldershot 2006, p.134.

See ‘Memorandum from the Parliamentary Committee’, 1945–1947, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/MIN/08789.

Arts Council, letter to the LCC, 27 January 1947, and its response, 3 April 1947, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/PK/01/054.

See Burstow 2006 and Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Public Sculpture in “New Britain” 1945–1953’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Leeds 2000, p.39.

See Margaret Garlake, ‘“A War of Taste”: The London County Council as Art Patron 1948–1965’, London Journal, vol.18, no.1, 1993, pp.45–65, and Dawn Pereira, ‘Henry Moore and the Welfare State’ in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/dawn-pereira-henry-moore-and-the-welfare-state-r1151315 , accessed 09 September 2015.

See Tenth Annual Report, Arts Council, London 1956–7, p.27, Archives of Art and Design, London, ACGB 32/186.

Moore’s work was included in open-air exhibitions in Sonsbeek Park, Arnhem, in 1955 and 1958, and in 1959 in Middelheim, Antwerp. The latter exhibition focused on British sculpture and included sixteen works by Moore. Its organisers wrote to the LCC to seek advice about the organisation of the exhibition (see LCC, letter to R. Pandelaers, 10 October 1955, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/PK/01/056).

See ‘Appendix A’, First Annual Report, Arts Council, London 1945–6, Archives of Art and Design, London, SCGB 32/186.

Charles Wheeler first used the phrase ‘war of taste’ in his essay in the 1957 catalogue. See Garlake 1993, pp.45–65.

Henry Moore quoted in Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites, edited by Robert Melville and recorded by the British Council 1955, http://www.henry-moore.org/works-in-public/world/uk/london/battersea-park/three-standing-figures-1947-lh-268 , accessed 2 September 2014.

See Andrew Stephenson, ‘Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/andrew-stephenson-fashioning-a-post-war-reputation-henry-moore-as-a-civic-sculptor-c1943-r1151305 , accessed 09 September 2015.

See Pauline Rose, ‘Henry Moore in America: The Role of Journalism and Photography’, in Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975, Los Angeles 2011, pp.32–44.

In 1959, for example, Moore received the highest number of votes (nineteen), with the next highest, Reg Butler, receiving only seven (Committee Report, 28 April 1959, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/PK/01/064). Moore (and Butler) also received the highest number of votes in 1956 (Committee Report, 12 July 1956, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/PK/01/060).

Jacob Epstein, letter to Peggy Jean Lewis (his daughter), undated, Tate Archive TGA 8716/5, cited in Burstow 2006, p.135.

See, for example, a Working Party Report which notes that ‘there would not be enough English sculpture of the highest class readily available’, 8 July 1947, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/PK/01/054.

This was the title given to the work in the exhibition catalogue. It is now known as Venus with a Necklace.

See Jennifer Powell, ‘A Coherent, National “School” of Sculpture? Constructing Post-War New British Sculpture through Exhibition Practices’, Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.2, 2012, pp.37–50. Herbert Read, ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’, in Exhibition of Works by Sutherland, Wadsworth, Adams, Armitage, Butler, Chadwick, Clarke, Meadows, Moore, Paolozzi, Turnbull. Organised by the British Council for the XXVI Biennale, Venice 1952, n.p.

Alan Bowness, ‘Introduction by Alan Bowness’, Sculpture in the Open Air, Greater London Council, London 1966, n.p.

Visitor maps are included in the 1960, 1963 and 1966 exhibition catalogues outlining the same area of land and entrance point.

See the visitors maps in Sculpture in the Open Air, Holland Park, London 1954, and Sculpture 1850 and 1950, Holland Park, London 1957, n.p.

Robert Melville, ‘Exhibitions Painting and Sculpture’, Architectural Review, vol.128, no.763, September 1960, p.222. The Pathé film Open Air Sculpture (1960) shows that the sculpture was positioned adjacent to a flat area of pathway and tall trees.

A lecturer named Barbara Naish recorded that she had well over a hundred attendees on a fine weekend afternoon and that Moore’s sculpture aroused the greatest interest (‘though a number of people were puzzled there was little real antagonism’, and ‘Henry Moore obviously stole the show’). Marjorie Lilly also recorded seventy to eighty people on a Saturday and eighty to hundred on a Sunday, and G. Myer-Morton recorded up to three hundred. Matvyn Wright noted that ‘almost everyone is charmed and delighted by the novelty of the occasions, and almost everyone wants to know what is the meaning of the Moore group’. See the Lecturer’s Reports, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/CL/PK/01/054.

John Read, British Art and Artists. A Sculptor’s Landscape, BBC television programme, broadcast 29 June 1958, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8802.shtml , accessed 26 June 2014.

LCC, letter to Eric Newton, 14 January 1948, cited in Brandon Taylor, Art for the Nation, Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747–2001, Manchester 1999, p.192.

See ‘Sculpture Exhibition Survey of Visitors’, 5 May 1960, London Metropolitan Archives LCC/PK/01/064.

See ‘White Without a Blemish’, Harper’s Bazaar, U.K., July 1948, pp.58–9; ‘At the Sculpture Exhibition in Battersea Park’ and ‘Painting and Sculpture’, Vogue, U.K., June 1948, pp.56–8, cited in Felice McDowell ‘“At the Exhibition”: The 1948 Open-Air Sculpture Exhibition, Battersea Park, in British Fashion Magazines’, in Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.1, 2012, pp.169–81.

Anon., ‘Battersea Park as an Open-Air Sculpture Gallery: Statues with a Background of Summer Foliage’, Illustrated London News, 22 May 1948, pp.588–9; and ‘Sculpture – Not Exactly in the Manner of Praxiteles: Modern Work in Battersea Park Open-Air Exhibition’, Illustrated London News, 19 May 1951, p.821.

Jennifer Powell is Senior Curator Collection and Programme at Kettles Yard, University of Cambridge.

How to cite

Jennifer Powell, ‘Henry Moore and ‘Sculpture in the Open Air’: Exhibitions in London’s Parks’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www