Henry Moore OM, CH Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 14

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963-5, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center)

1963-5, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This work served as the preparatory model for a monumental sculpture of a reclining figure commissioned for the Lincoln Center in New York. According to Moore the two pieces of the sculpture represent a human body and a rock rising from water, while their formal affinities exemplify the way in which figures and landscapes coalesce in his work.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center)

1963–5, cast date unknown

Bronze

2350 x 3723 x 1652 mm

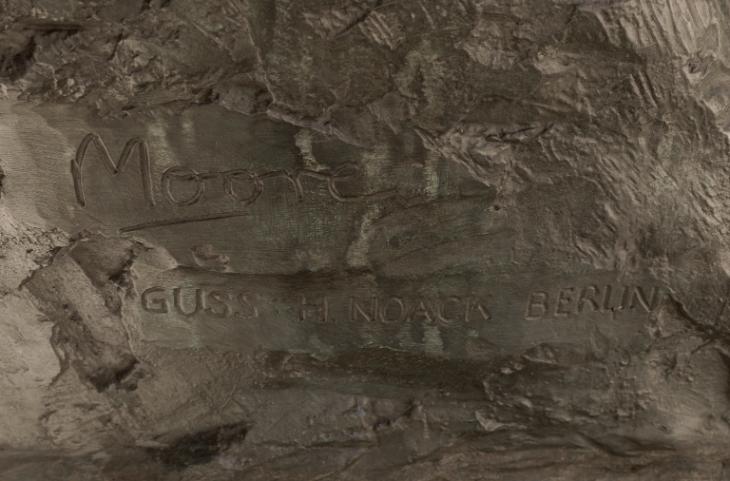

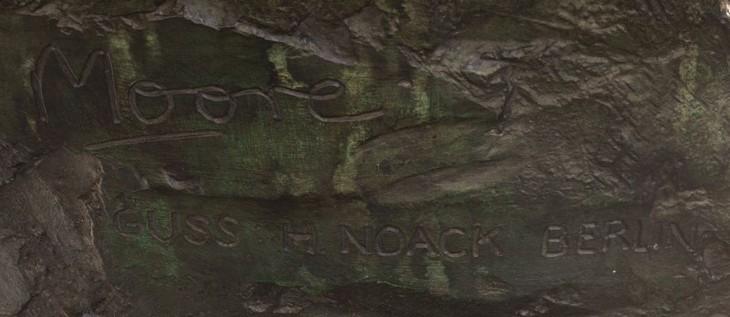

Inscribed ‘Moore’ and stamped ‘GUSS : H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower rear of torso

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 2

T02295

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center)

1963–5, cast date unknown

Bronze

2350 x 3723 x 1652 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ and stamped ‘GUSS : H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower rear of torso

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 2

T02295

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.130.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.128.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

2004–5

Henry Moore: Imaginary Landscapes, The Henry Moore Foundation, April 2004–October 2004; Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan, January 2005–May 2005.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.250, reproduced pls.239–40.

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966, pp.161–73.

1966

Alan Bowness, Greater London Council Exhibition, Battersea Park, London 1966, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London 1966 (another cast reproduced).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.193–4.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.345, 407–8.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.93, reproduced pl.89.

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973, pp.169–200.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, reproduced pl.133.

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.518 (?another cast reproduced pls.8–11).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (Reclining Figure 1963–5 reproduced pp.328–37).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.55.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.184–5 (original plaster reproduced pl.164).

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979, p.95, reproduced.

1980

Edgar B. Young, Lincoln Center: The Building of an Institution, New York 1980, pp.203–20 (Reclining Figure 1963–5 reproduced p.191).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.135–6, reproduced p.135.

1988

Richard Cork, ‘An Art of the Open Air: Moore’s Major Public Sculpture’, in Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.14–26.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Reclining Figure 1963–5 reproduced, pp.80–1).

Technique and condition

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

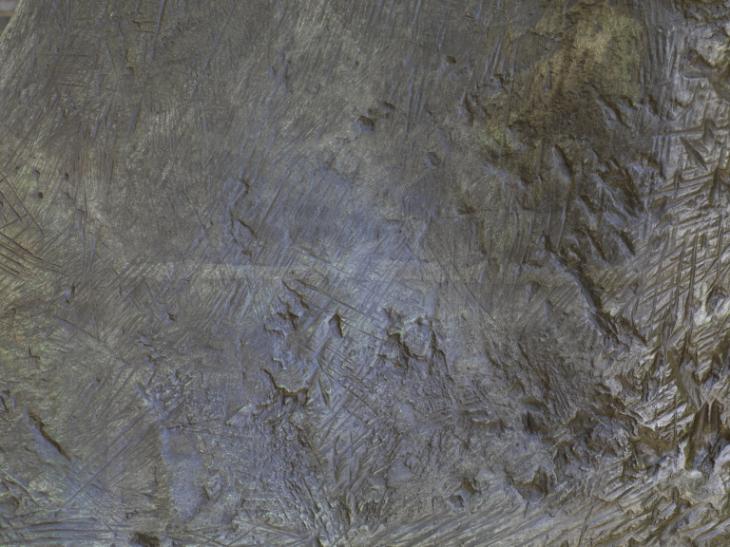

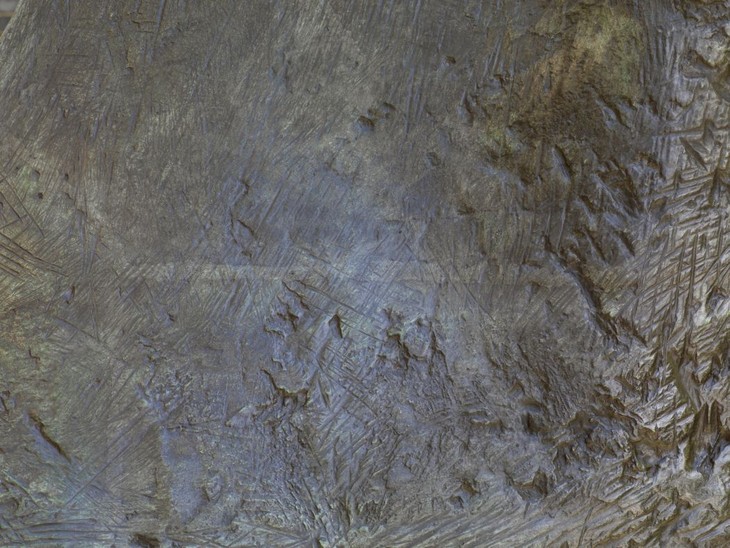

The bronze sculpture originated from a plaster model that Moore would have made by building up wet plaster over a supportive armature, perhaps made of wood and metal. Looking at the surface texture it is clear that Moore fully exploited the material properties of plaster to produce many different surface effects. Wet plaster would have been freely applied using a spatula but deep grooves indicate that the plaster was shaped when it began to set (fig.2). The many striations evince the use of pointed tools (fig.3), while other marks suggest that Moore also used a surform tool or grater when the plaster was the texture of ‘cheese hard’. After completion, a mould was taken of the two plaster parts which was used to cast the sculpture in bronze at the foundry.

Detail of gouges in surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of gouges in surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of striations on surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of striations on surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of casting seam on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of casting seam on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

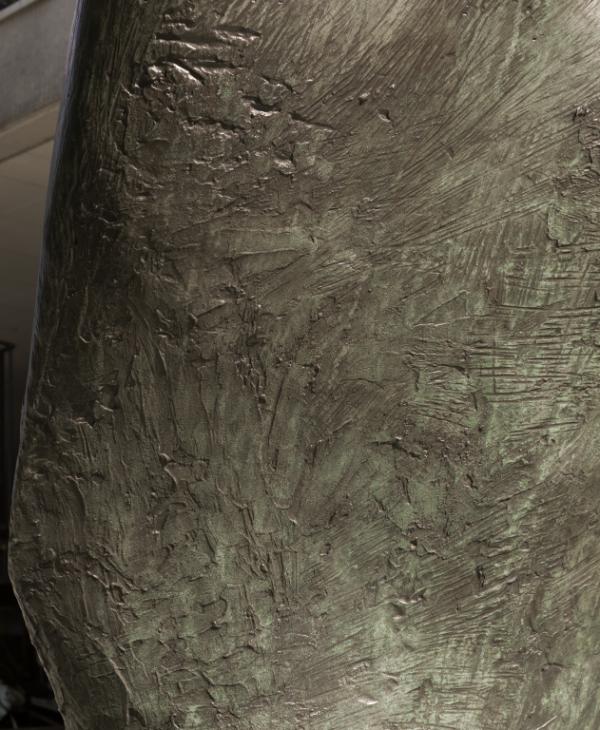

The final stage of fabrication involved applying an artificial patina to the bronze surface, created by applying chemical solutions to the bronze that reacted with the surface to produce coloured compounds. This sculpture has been displayed outdoors for many years and so its original uniform brown patina has altered slowly due to exposure to the elements. As a result parts of the surface have turned green, particularly on the high points (fig.5).

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

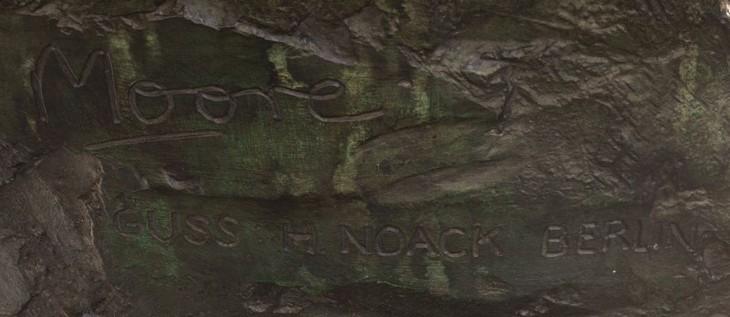

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the sculpture left the foundry it would have been given a coating of wax to protect it. This wax coating is replenished on an annual basis as part of Tate’s ongoing conservation programme for all its outdoor sculptures. It is also examined to check for any signs of degradation, and washed to remove bird lime and dirt. A resin is also applied to help protect the bronze at the waterline.

The artist’s signature and foundry mark are both visible on the back of the torso (fig.6)

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore’s two-part sculpture Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5 comprises two separate bronze elements that together may be understood to represent a reclining human figure. The sculpture was the working model for a much larger work commissioned for the Lincoln Center in New York City. The larger sculpture was designed to be placed in a large ornamental pool of water in front of the building, where it was installed in 1965. Tate’s working model for this sculpture is currently on long-term loan to the Charing Cross Hospital in London, where it is also installed outdoors in a pool (fig.1).

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown, installed at Charing Cross Hospital, London

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown, installed at Charing Cross Hospital, London

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The pose of a reclining figure – created by an upright torso and horizontally-arranged legs – was a motif that preoccupied Moore for much of his career. Works such as Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387) and Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825) are earlier examples of Moore’s engagement with the subject, which from 1959 went in a new direction when Moore began to systematically segment his reclining figures into two and three pieces, as can be seen in Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960 (Tate T00395) (fig.2). In 1961 Moore explained:

In doing these Reclining Figure sculptures (No.1 in 1959 and No.2 in 1960), it came naturally and without any conscious decision, that I made them in two separate pieces, the head-and-body end and the leg-end. In both sculptures I realised that I was simplifying the essential elements of my reclining figure theme ... In many of my reclining figures the head-and-neck part of the sculpture, sometimes the torso part too, is upright, giving contrast to the horizontal direction of the whole sculpture.1

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) represents a continuation and development of these earlier ideas and forms. The sculpture comprises an upright torso part and a separate block-like part, which, judging by the title and Moore’s earlier manifestations of this subject, would seem to denote the legs. The torso section is wide and thin and marked by irregular curvaceous protrusions. A thin slither of bronze marks the tallest point of the sculpture and may be recognised as a head due to its position within the composition, although it possesses no recognisable facial features. The rear of the head is reminiscent of a fin that extends down the figure’s back to create a ridged backbone, which divides the back into two similarly sized sections (fig.3). Two broad shoulders round off the top of the torso, which does not have arms. On the left shoulder is a triangular shaped depression, the edge of which is akin to a collar bone. The torso remains approximately the same width from shoulders to hips, at which point it splits into two truncated appendages separated by an arch. Seen from the side, the torso appears to lean forwards at a diagonal angle towards the other section of the sculpture (fig.4).

Leg section of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Leg section of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Leg section of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Leg section of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The second, smaller section of the sculpture comprises two differently shaped and highly textured vertical columns connected by a smooth, curved sheet of bronze that creates an almost tubular hollow between them (fig.5). This linking curve arches over the gap but also extends backwards to create a fin-like protrusion (fig.6). The heavily textured surfaces, overhanging edges and rounded hollows of this part of the sculpture are reminiscent of seafront caves and eroded cliffs, allusions that are accentuated by its placement in water.

The Lincoln Center commission

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1963–5 Lincoln Center, New York

Bronze

Lincoln Center, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1963–5 Lincoln Center, New York

Lincoln Center, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From studio to foundry

Flint stone from Henry Moore's collection on display at Marlbrough Gallery, London, June 1971

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Flint stone from Henry Moore's collection on display at Marlbrough Gallery, London, June 1971

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.5

Moore made numerous maquettes for two-piece sculptures between 1959 and 1964 using these techniques, sometimes making only very slight alterations between each one. Not all of these maquettes were scaled up into full size sculptures, although some were cast in bronze as small table-top sculptures. Moore explained:

Sometimes I make ten or twenty maquettes for every one that I use in a large scale – the others may get rejected. If a maquette keeps its interest enough for me to want to realise it as a full-size final work, then I might make a working model in an intermediate size, in which changes will be made before going to the real, full-sized sculpture. Changes get made at all these stages.6

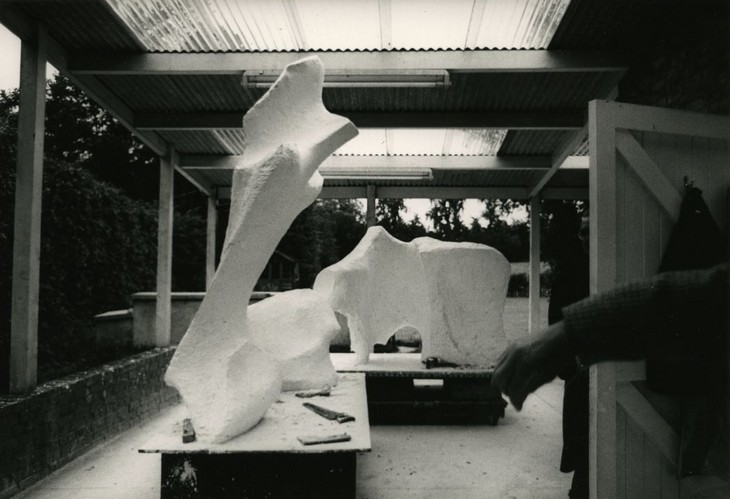

According to Moore’s biographer Donald Hall, Moore made a series of small maquettes for the Lincoln Center project in the summer of 1962.7 It is not known whether the final plaster maquette for Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) survived, and no bronze casts of it were made. However, in addition to this maquette, one other design under consideration for the Lincoln Center site was enlarged in plaster to an intermediary, ‘working model’ size. This second sculpture became Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4 (Tate T02294), and is identified as an ‘alternative project for the Lincoln Center Sculpture’ in the artist’s catalogue raisonné.8 The enlargement process, which was undertaken in the winter of 1962–3, would have involved charting and measuring specific points on the surface of the maquettes to ensure the sculptures were scaled up accurately. Scaling-up was carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands or, if the weather was fine, outdoors on the studio terrace (fig.9).9 Much of this work would have been undertaken by one or more of Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1962–3 included Geoffrey Greetham, Robert Holding, Roland Piché, Ron Robertson-Swann, and Isaac Witkin.

Moore’s assistants would have initially constructed an armature to the required size and rough shape for each section of the sculpture. The armature would have been made up of numerous lengths of wood and possibly chicken wire, and then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric. Successive layers of plaster were then built up over the hollow structure until only a short section of each armature rod was exposed. The armature served not only a structural purpose, but was also used to facilitate the enlargement process, with the end of each rod corresponding to a precise point on the surface of the sculpture.10 After modelling the sculpture to the required shape and size, Moore would then have concentrated on the surface texture. Using an array of tools – including saws, chisels, and files – he created different types of markings, grooves and cuts depending on the wetness of the plaster. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.11 The surface of the plaster was captured in the casting process and an examination of the bronze surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) shows how Moore created a range of textures using a number of different tools including fine points, graters and spatulas (fig.10).

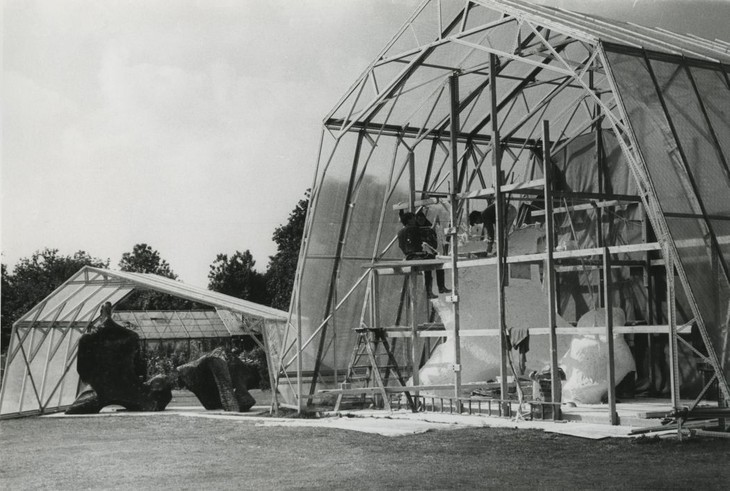

Plaster version of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) at Hoglands c.1962–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Plaster version of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) at Hoglands c.1962–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of gouges in surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of gouges in surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s assistants would have initially constructed an armature to the required size and rough shape for each section of the sculpture. The armature would have been made up of numerous lengths of wood and possibly chicken wire, and then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric. Successive layers of plaster were then built up over the hollow structure until only a short section of each armature rod was exposed. The armature served not only a structural purpose, but was also used to facilitate the enlargement process, with the end of each rod corresponding to a precise point on the surface of the sculpture.10 After modelling the sculpture to the required shape and size, Moore would then have concentrated on the surface texture. Using an array of tools – including saws, chisels, and files – he created different types of markings, grooves and cuts depending on the wetness of the plaster. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.11 The surface of the plaster was captured in the casting process and an examination of the bronze surface of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) shows how Moore created a range of textures using a number of different tools including fine points, graters and spatulas (fig.10).

After they were completed, the two working models were applied with colour to make the plaster look more like bronze. Moore did this ‘because on white plaster the light and shade acts quite differently, throwing back a reflected light on itself and making the forms softer, less powerful ... even weightless’. 12 Importantly, it also allowed Moore to gauge what the two darkly coloured bronze sculptures would look like in water. The two painted plaster working models were thus positioned within a small swimming pool at Hoglands (fig.11).13 Following this test, Moore concluded that Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 ‘was not so good at rising out of the water’ and so the decision was made to enlarge Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) for the New York commission.14

Plaster version of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) in pool at Hoglands c.1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Plaster version of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) in pool at Hoglands c.1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Plaster versions of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5 and Reclining Figure 1963–5 at Hoglands c.1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Plaster versions of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5 and Reclining Figure 1963–5 at Hoglands c.1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Having decided which sculpture he wanted to make, Moore set to work building the full-size plaster in a specially constructed studio on the grounds at Hoglands (fig.12). The full-size plaster was completed in August 1964, whereupon it was carved into pieces and shipped to the Noack Foundry in Berlin, where the individual parts were cast in bronze before being welded together. During the 1950s and early 1960s Moore used a number of different foundries in London and Paris but started working with Noack in 1958 following an introduction by the dealer Harry Fischer.15 By then Noack was regarded as one of the best bronze foundries able to undertake large-scale castings and in 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.16 The casting, welding and patinating of Reclining Figure 1963–5 took almost a year to complete, but the finished work was flown to New York in July 1965.

Given the timescale involved in creating the Lincoln Center Reclining Figure, it is likely that Moore only considered casting the plaster working model into bronze after the full-size version had been installed in New York. Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) was also cast at the Noack Foundry, in an edition of two. The sculpture is inscribed with Moore’s signature and stamped with the foundry mark on the back of the figure towards the bottom (fig.13).

It is unclear which casting technique was used to create this bronze sculpture, but whether the lost wax or sand casting method was used, the foundry technicians at Noack would still have had to carve up the plaster sculpture into smaller pieces so that moulds could be created of each piece. The inside of each mould would then have been filled with molten bronze. After the bronze had hardened it was removed from the mould revealing a section of sculpture. Once all the pieces of the sculpture had been cast they would be welded together. Finally, the casting seams would have been filed down so that the joins between each section were practically imperceptible.

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Torso of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After being assembled at the foundry the bronze sculpture was probably returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. This sculpture has a dark brown patina, overlaid with green shades that have probably developed over time as a result of exposure to the elements (fig.14). In 1963 Moore asserted, ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, explaining that since he had conceived the sculpture it would be unlikely that someone else would be able to replicate the exact colour he wanted.17 However, it is known that Noack would sometimes patinate Moore’s sculpture at the foundry. But even in these instances Moore was still able to adjust the patina when the sculpture was returned to the studio.

Sources and development

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

Green Hornton stone

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Also in my reclining figures, I have often made a sort of looming leg – the top leg in the sculpture projecting over the lower leg, which gives a sense of thrust and power – as a large branch of a tree might move outwards from the main trunk – or as a seaside cliff might overhang from below, if you are on the beach.20

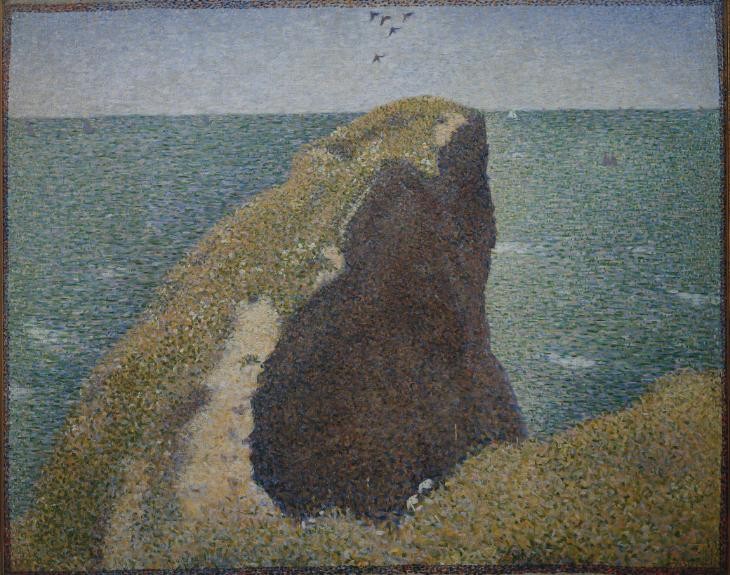

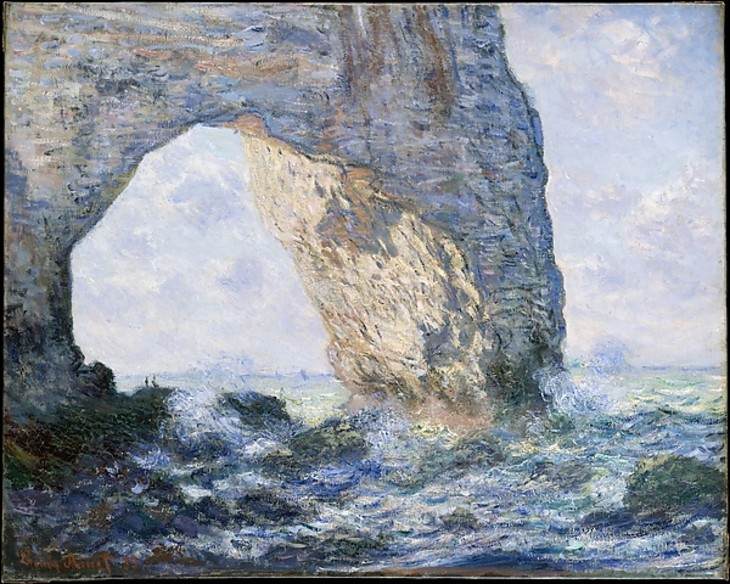

Reflecting on the traces of landscape in Moore’s reclining figures, the critic David Thompson wrote in 1965, ‘I think it could be claimed that Moore is the first sculptor in history to have found a way of expressing his feelings about landscape. Formerly only painters could describe mountains and cliffs and sea-caves’.21 Thompson went on to state that in Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center), Moore referred ‘not only to costal scenery but to a specific coastal scene, namely the famous rock at Etretat which appears in paintings by Courbet, Monet, Renoir and others’.22 Following up this point, the critic John Russell has argued that two specific paintings contributed to the compositional form of the Lincoln Center sculpture: Claude Monet’s The Manneporte (Étretat) 1883 (fig.16) and George Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp 1885 (Tate N06067) (fig.17), which was owned by Moore’s close friend, the art historian Kenneth Clark.23 While the arched cliff painted by Monet resembles the smaller, hollowed part of Moore’s sculpture, the steep promontory depicted in Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp may be compared to the curvaceous protrusions found on the sculpture’s torso, most notably that of the figure’s head.24

Claude Monet

The Manneporte (Étretat) 1883

Oil paint on canvas

654 x 813 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2000–2015 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All rights reserved

Fig.16

Claude Monet

The Manneporte (Étretat) 1883

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2000–2015 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All rights reserved

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Pyinkado wood

279 x 546 x 308 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

‘A supreme symbol of our human destiny’

As the final work to be discussed in Herbert Read’s 1965 monograph on Henry Moore, the Lincoln Center Reclining Figure (and thereby the working model) is described in exaggerated terms:

This piece is the extreme evolution of those variations of the reclining figure motive in which the extended limbs are magnified until they form a massive cliff-like extension, pierced by an arch. The torso rises against this rocky mass with a volcanic violence, in which, however, some element of the eternal feminine still confronts the general sense of the earth’s indifference. Set in water, this impassive monument is reflected against the changing moods of the overreaching sky. The Great Mother, the Goddess of Fertility, life itself as a tender force, broods over the desolated alters of a Waste Land. The creative genius of our artist has finally led us to a supreme symbol of our human destiny.26

Moore’s continuous preoccupation with the subject of the reclining female figure led numerous critics to suggest that he was seeking to present an archetypal vision of the human form.27 As early as 1953, Read, who was a life-long supporter of Moore’s, asserted that ‘in modern Europe we cannot avoid certain humanitarian preoccupations ... The modern sculptor, therefore, more naturally seeks to interpret human form’.28 Moore, according to Read, distinguished himself from his contemporaries by relating ‘the human form to certain universal forms which may be found in nature’.29 By uniting human and natural forms, as can be seen in Moore’s allusions to rocks or bones in Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center), Moore was able to break free of what Read saw as the ‘false imprisonment’ of mimetic representation. In his 1953 book Read supported his interpretation by quoting a statement written by Moore in 1934:

Because a work of art does not aim at reproducing natural appearances it is not, therefore, an escape from life – but may be a penetration into reality, not a sedative or drug, not just the exercise of good taste, the provision of pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination, not a decoration to life, but an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to greater effort of living.30

These beliefs underpinned Moore’s later work, and anticipated the comment he made in 1967 that when looking for human implications in natural forms, ‘taste is not the guide. I’m not interested in the niceties of a shape’.31 In attempting to create a union of the human body and landscape, Moore identified humanity and the environment as partners within an ‘organic whole’.32

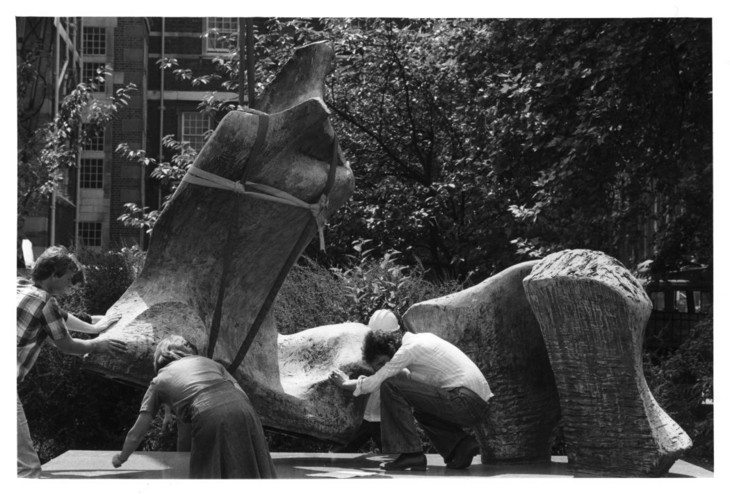

The Henry Moore Gift

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–65, cast date unknown being installed in the garden at Tate in 1978

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–65, cast date unknown being installed in the garden at Tate in 1978

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In the years following the eightieth birthday exhibition Reid and the Tate trustees decided to loan some of Moore’s large-scale works to venues across the country on a long-term basis rather than keep them in storage. Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) has been on loan to the Charing Cross Hospital, London, since 1980, where it is displayed in a specially designed pool.

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) exists in an edition of two bronzes. The plaster sculpture from which the bronze was cast is held in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

Henry Moore, ‘Two-Piece Reclining Figures 1959 and 1960’, artist’s statement sent to Martin Butlin, 13 April 1961, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945, reprinted in Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, vol.2, p.28.

Iain A. Boal, ‘Ground Zero: Henry Moore’s Atom Piece at the University of Chicago’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.224.

Henry Moore cited in Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, summer 1967, pp.352–8.

In 1934 Moore stated that ‘The observation of nature is part of an artist’s life, it enlarges his form-knowledge’. See Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, London 2002, p.192.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

See Anne Wagner, ‘Scale in Sculpture: The Sixties and Henry Moore’, Tate Papers, no.15, spring 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/scale-sculpture-sixties-and-henry-moore , accessed 13 August 2013.

Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, p.159.

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.193. It is known that Moore saw the Seurat painting regularly during his visits to Clark’s home. See Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.269.

Other writers, including Herbert Read, Robert Melville, and Alan Wilkinson, have also compared Moore’s work to the depiction of cliffs in paintings by Claude Monet and Georges Seurat. See Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.227; Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.29; Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.193.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Henry Moore’s Photographic Identity Marin R. Sullivan

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www