Henry Moore OM, CH Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955-6, cast 1958-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross

1955-6, cast 1958-60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross is one of a series of standing sculptures made by Moore between 1955 and 1956. It takes its name from the Glenkiln Estate in Scotland where the first cast was originally placed. While its formal characteristics have prompted comparisons with Moore’s earlier surrealist works and prehistoric art, its evocation of Christian imagery was strengthened by Moore’s own retrospective comments.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross

1955–6, cast 1958–60

Bronze

3327 x 978 x 965 mm

Presented by Mary Danowski (née Moore) 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02274

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross

1955–6, cast 1958–60

Bronze

3327 x 978 x 965 mm

Presented by Mary Danowski (née Moore) 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02274

Ownership history

Gift of the artist to his daughter Mary Moore before 1960, by whom presented to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1958

50 ans d’art moderne, Palais International des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, April–July 1958 (?another cast exhibited no.234).

1960–1

Sculpture in the Open Air, Battersea Park, London, May–September 1960, no.32.

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961, no.27.

1964

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore at King’s Lynn, St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, July–August 1964, no.2.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.95.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.39.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972 (?another cast exhibited no.93).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976 (?another cast exhibited no.51).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.134.

2013

Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, September 2013–January 2014.

References

1958

50 ans d’art moderne, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1958, reproduced p.206.

1960

Sculpture in the Open Air, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London 1960, pp.19–20.

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960, reproduced no.27.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.197–215, reproduced pls.155–6.

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962, reproduced pp.15–18.

1964

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore at King’s Lynn, exhibition catalogue, St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn 1964, reproduced.

1965

Henry Moore, John Russell and A.M. Hammacher, Drie Staande Motieven, Otterlo 1965 (another cast reproduced).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.377 (?another cast reproduced pls.4–7).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.203–8 (?another cast reproduced pl.191).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.253–7 (?another cast reproduced pls.108–10).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.127, reproduced pp.131, 144.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.164, 245, 250 (?another cast reproduced p.244).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.141–56 (another cast reproduced pls.143, 162).

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo 1969 (another cast reproduced).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, pp.28, 212 (?another cast reproduced pls.42, 503).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972 (?another cast reproduced pp.164–5).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, pp.165–83 (?another cast reproduced pls.89, 101).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Zürcher Forum, Zürich 1976 (?another cast reproduced p.202).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (other casts reproduced pp.148–51, 306–7, 484).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced pp.32–3.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.135–9 (first cast reproduced no.116, original plaster reproduced pl.106).

1981

[Richard Morphet], ‘Upright Motive No.1 Glenkiln Cross’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.120–1.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.87.

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.158–61 (original plaster reproduced no.106).

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, reproduced p.237.

1991

Virtue and Vision: Sculpture and Scotland 1540–1990, exhibition catalogue, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh 1991 (another cast reproduced p.112, no.113).

1993

John McEwen, Glenkiln, with photographs by John Haddington, Edinburgh 1993 (another cast reproduced pp.56, 60–3).

1998

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, pp.191–2.

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003 (another cast reproduced no.115).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (another cast reproduced, p.70).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.203–7 (other casts reproduced nos.248, 251).

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011 (original plaster reproduced nos.81, 85).

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013, reproduced.

Technique and condition

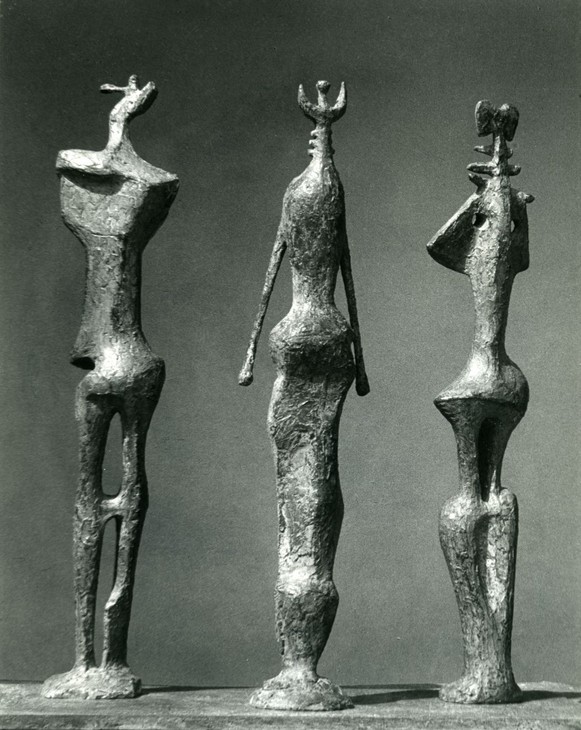

Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture by applying successive layers of plaster over a supportive armature, probably made using lengths of wood, chicken wire and scrim bandage. The surface of the sculpture evidences the use of a variety of techniques including marks made by adding wet plaster with a spatula (fig.2) and lines incised in the setting surface with pointed tools and serrated edges (fig.3). Moore also treated the hardened plaster like stone, using chisels to carve it and rasps and files to smooth it. In this way he combined the techniques of modelling and carving to produce the finished sculpture.

Detail of surface of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of surface of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of upper section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 showing incised lines

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of upper section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 showing incised lines

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore added further surface detail using the technique of graffito, which involves making lines in the plaster while it is still slightly wet. This is illustrated by the panel on the lower section of the sculpture where vertical lines and circles have been incised into its surface (fig.4). Equally, the semi-circular form that appears directly above the base and the vertical ridges that appear on the opposite side of the column (fig.5) demonstrate how Moore used relief to enhance particular forms.

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of vertical ridges on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of vertical ridges on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the plaster was complete a mould was taken from it so that it could be cast in bronze. This sculpture was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy. Moore had the first four versions cast at Corinthian Bronze Foundry in Cambridgeshire, and then a further three cast at Noack Foundry in West Berlin, with one of these kept as the artist’s copy. Although it is not signed, Tate’s version is the artist’s copy and was probably the last to be cast. The maximum size of any one piece of cast bronze depends upon the size of the crucible at the foundry, as the molten bronze used to make the sculpture must be poured into the mould in one go. In practice this means that bronzes of this size are usually cast in sections and welded together. This sculpture appears to have been divided horizontally into three roughly equal parts, as evidenced by the trace of a horizontal weld line on the side of the sculpture (fig.6). These welds would have been filed and textured with punch tools to match the surrounding bronze surface through a process called ‘chasing’. Although the surface of the bronze can be examined to ascertain where on the sculpture such processes were used, it does not provide definitive proof of the casting technique used.

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross has been displayed in the open air for many years and its original colour has altered gradually from exposure to the weather. Most bronze sculptures displayed outdoors eventually develop a green hue as a result of chemical weathering. This green is often brighter on exposed high points, as the sculpture’s present condition demonstrates (fig.8).

Detail of lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 showing abrasion

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 showing abrasion

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 Detail of lower section showing abrasion

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 Detail of lower section showing abrasion

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

While situated at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), sheep have also affected the appearance of this sculpture. Since its foundation in 1977 YSP has worked with local farmers, allowing flocks of sheep to graze on parts of its 500 acre estate. The sheep have used the sculptures on display as shelters, and their slightly abrasive wool has removed the patina around the base of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross leaving visible golden edges (fig.9).

When the sculpture left the foundry it would have been given a coating of protective wax, which is replaced annually as part of an ongoing maintenance programme. This procedure involves washing the surface to remove dirt deposits and bird lime before the new wax is applied. A black wax has been used for its maintenance in the past, and this has both darkened the patina and left residues in the recesses of the sculpture.

The sculpture is unsigned and fixed to a rectangular bronze base, most likely by bolts from underneath. The base was probably cast using the sand casting technique and then given a smooth finish by applying an abrasive. For stability, outdoor sculptures like this are usually fixed into a concrete foundation underneath the base.

Lyndsey Morgan

May 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', May 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross is a tall, vertically-orientated sculpture consisting of two distinct parts: the upper half comprises a loosely cross-shaped mass while the lower half takes the form of a columnar plinth. Although designed to be seen in the round, the side featuring a relief panel with a half moon is conventionally regarded as the front of the sculpture (fig.1).

The upper half of the sculpture resembles a warped Latin cross. The central shaft, which is deeper than it is wide, tapers outwards as it extends upwards from an irregular bulbous form or burr. Approximately two thirds up this shaft are two fin-like, irregular stumps or arms that project almost horizontally from either side of the central axis, which culminates in a narrow but deep, semi-cylindrical shape with domed faces at the front and back. A truncated, rounded swelling protrudes from the front in between the central shaft and the right arm.

The lower section of the sculpture is a tall cuboid, patterned on the front and rear with surface designs. The front side features a rectangular relief with a curved lower edge (fig.2). It is incised with parallel and equidistant vertical lines, two of which (towards the left) have been linked by a series of short horizontal incisions. A circular depression can also be seen towards the lower right of this relief interrupting the lines, which terminate just above a raised crescent, into which another smaller crescent has been etched. Another raised form – a disk with a depression just above its centre – can be seen just above the relief’s curved lower edge, which cuts deeply into the surface but tapers off to the right-hand edge of the cuboid. At the base of the sculpture there are two rectangular indentations of different sizes.

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of graffito on lower section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The rear side of the sculpture’s lower half is textured with five vertical ridges and capped with a curved lip (fig.3). Combined with the vertical lines on the facing relief, these features further identify the cuboid with a plinth or column, specifically evoking the fluting of an ionic column.

Detail of surface markings on Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of surface markings on Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture’s lateral surfaces are not patterned with relief designs. However, the different surface textures found on the sculpture are most evident on these side surfaces. The upper part in marked with shallow grooves and cuts while the lower section has been smoothed and then incised with fine cross-hatched lines, probably made with a knife or another sharp tool (fig.4). Moore would have applied these surface textures to the original plaster version knowing that they would be reproduced during the bronze casting process.

Making the Upright Motives

Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross is one of a series of vertically-orientated sculptures known as ‘upright motives’ that Moore made between 1955 and 1956. Moore created a total of thirteen small maquettes for individual sculptures in the series, of which five (numbers 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8) were enlarged to full size. In addition to Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross, casts of Upright Motive No.2 1955–6 (Tate T02275) and Upright Motive No.7 1955–6 (Tate T02276) are held in the Tate collection. Discussing Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross in 1968, Moore recalled:

The maquettes for this upright motif theme were triggered off for me by being asked by the architect to do a sculpture for the courtyard of the new Olivetti building in Milan. It is a very low horizontal one-storey building. My immediate thought was that any sculpture that I should do must be in contrast to this horizontal rhythm. It needed some vertical form in front of it. At the time I also wanted to have a change from the Reclining Figure theme that I had returned to so often. So I did all these small maquettes. They were never used for the Milan building in the end because, at a later stage, when I found that the sculpture would virtually be in a car park, I lost interest. I had no desire to have a sculpture where half of it would be obscured most of the day by cars. I do not think that cars and sculptures really go well together.1

Henry Moore

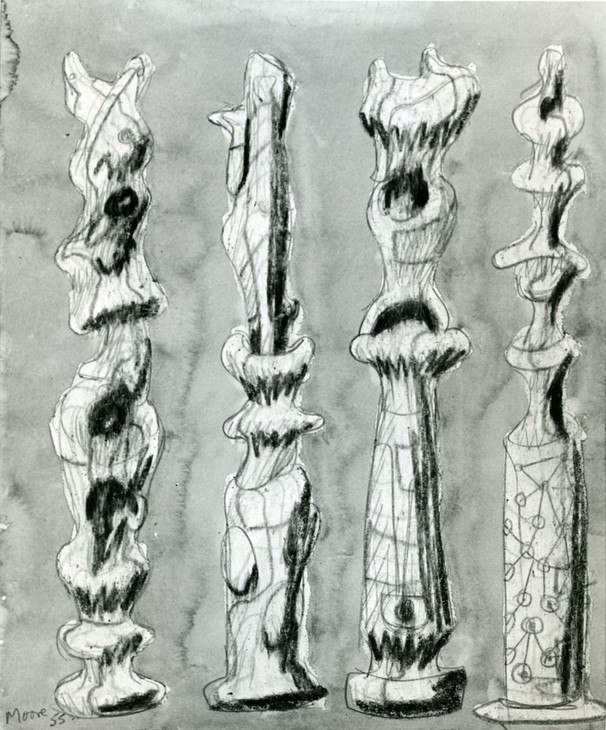

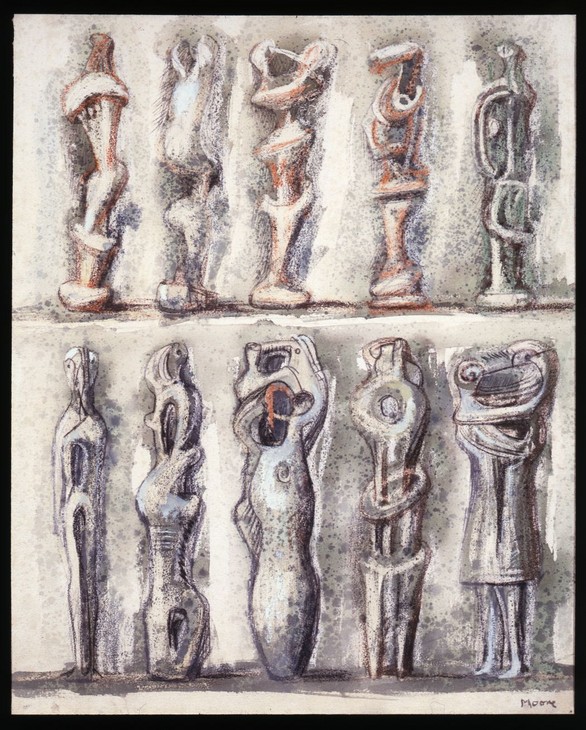

Upright Motives 1954–6

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, pastel and watercolour wash on paper

289 x 238 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Upright Motives 1954–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In 1978 Moore described his working practice, saying, ‘I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture ... I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle’.4 The plaster maquette for Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross, known as Upright Motive: Maquette No.1, dates from 1955 and was probably made in Moore’s maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. Previously the village shop, the building was used by Moore from the early 1950s as a private space in which he could conduct preliminary experiments before moving to the larger studio to develop his work on a larger scale. Moore’s plaster maquette studio was lined with shelves on which his ever growing collection of bones, shells, and pebbles – what he called his ‘library of natural forms’ – was stored.5 Surrounded by these objects, Moore appropriated their shapes when creating his own sculptures. In 1963 he explained to the critic David Sylvester how he worked with found natural objects:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.6

In 1955 Moore was just beginning to develop the working technique he described confidently to Sylvester in 1963. It is likely that the top half of Upright Motive: Maquette No.1 developed from pieces of plaster cast from the impression left by a stone or bone pressed into clay or plasticine. Once these pieces of plaster had hardened Moore could then add and subtract forms and smooth or sharpen edges to make the final plaster maquette. The lower cuboid portion of the maquette was probably made from a piece of solid plaster into which Moore carved his relief designs.

Once Moore was happy with the design of his maquette a full-size plaster version was made. Using the maquette as a template, an armature, possibly made of wood and wire netting would first be constructed. Over this structure layers of plaster were built up and the sculpture would begin to gain mass and form. The full-size plaster of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross would have been created in the White Studio at Hoglands by Moore’s studio assistants, who at the time included Daryll Hill, Peter King, Lenton Parr and Stephen Walker. Moore was able to allocate the bulk of the preliminary work to others because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, the enlargement process was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.7

When the full-size plaster version was near completion Moore would inspect it and finish the details on the surface before sending it to a foundry for casting. Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy. Of the seven existing casts, four were cast at Corinthian Bronze Foundry, Cambridgeshire, and a further three were subsequently cast at Noack Foundry in West Berlin. It is known that during the 1950s Moore used a number of different foundries in London and Paris, but started working with Noack in 1958 following an introduction made by the dealer Harry Fischer of Marlborough Fine Art, London.8 In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.9 It is uncertain when Tate’s copy of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross was cast, but records held at the Henry Moore Foundation state that it was initially listed as number seven of the edition suggesting that it was the last to be cast. Tate’s example was later renumbered ‘0’, indicating that it was the artist’s copy.

At the foundry the technicians used the plaster original to create hollow moulds into which molten bronze could be poured. Due to its size, the sculpture was probably cast in three sections and then welded together. A welding seam can be distinguished traversing the circumference of the upper section of Tate’s cast (fig.6).

Detail of welding seam on Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of welding seam on Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60

Tate T02274

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore's assistants patinating bronze sculptures from the upright motive series c.1958–60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Fig.7

Moore's assistants patinating bronze sculptures from the upright motive series c.1958–60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculpture would have been returned to Moore so that he could examine its quality and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze sculpture. In 1968 Moore remarked upon an undated photograph of his studio assistants patinating bronzes from the upright motive series (fig.7), explaining that, ‘my assistants are patinating the upright motifs [sic], to give them the colour and surface quality I wanted. In my sculpture, whilst of course colour counts, it’s not the main thing. Otherwise I would have been a painter’.10 Tate’s copy of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross is predominantly dark brown and black, although some areas have turned green, particularly towards the top of the sculpture. As Moore explained, ‘bronze naturally in the open air (particularly near the sea) will turn with time and the action of the atmosphere to a beautiful green’.11

Sources and development

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

Wood

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1953

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

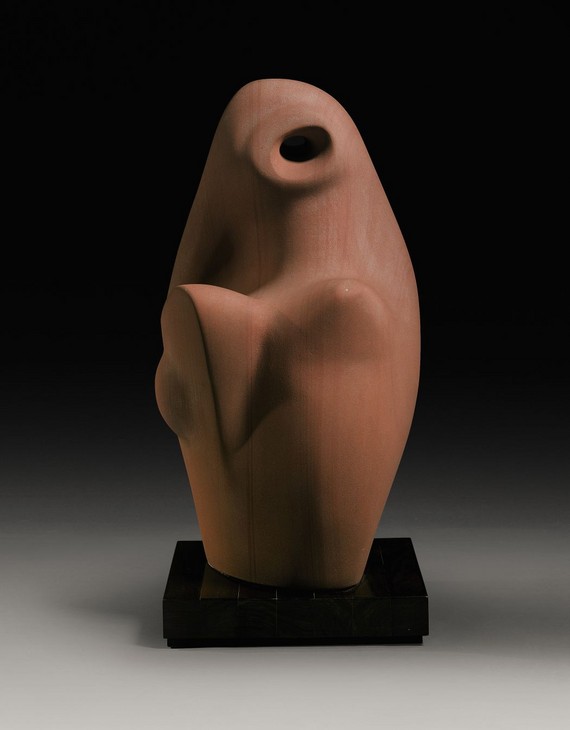

Henry Moore

Small Relief: Lower Half of 'Upright Motive: Maquette No.1' 1955

Terracotta

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Small Relief: Lower Half of 'Upright Motive: Maquette No.1' 1955

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

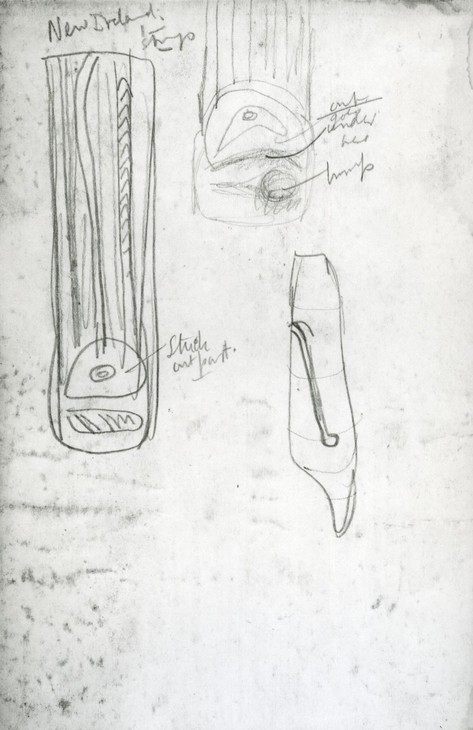

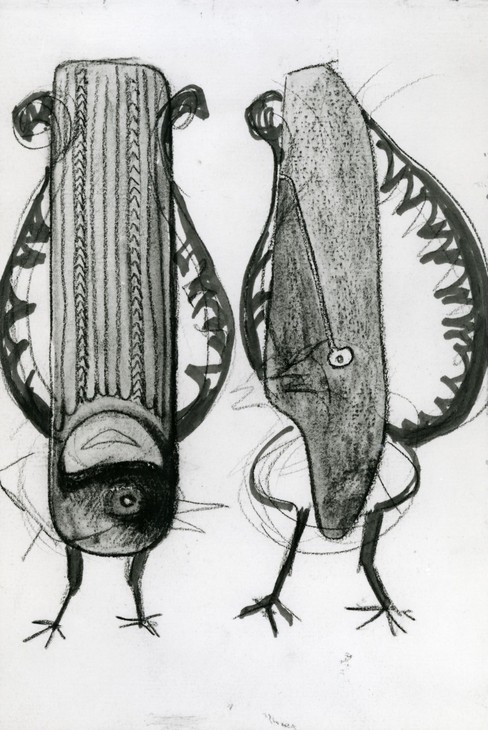

In 1955, when he began work on the Upright Motive series, Moore made a unique terracotta version of the striated rectangular relief found on the front of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross (fig.10). Although the small sculpture contains elements not found in the final version – principally the two small round indentations visible at the top – other features are included, such as the column of horizontal striations on the left-hand side. The curator Alan Wilkinson has suggested that the relief and its designs were conceived in a drawing made by Moore in c.1935 (fig.11). The sketch in the upper left-hand corner of this drawing presents a vertical form comprised of vertical parallel lines that terminate at a pair of rounded shapes at the bottom. The page is annotated with the words, ‘New Ireland | strings’, indicating the geographical area where the depicted object was made and, perhaps, the character of the vertical lines.15 New Ireland is a large island in Papua New Guinea and Garrould has suggested that Moore may have sketched the ‘shield or implement whilst on a visit to the Ethnographical department of the British Museum’.16 Although the original source has not been identified, it is known that Moore made regular trips to the museum following his arrival in London in 1921 and used its collection of prehistoric, medieval and non-Western art as a source of inspiration for sculptural ideas throughout his career. In 1980 Moore was invited to identify artworks from the British Museum collection that had influenced his work, and these were then collated for publication in the photographic book Henry Moore at the British Museum (1981).17 Discussing two sculptures from Papua New Guinea included in this book, Moore noted that ‘the Oceanic peoples appear to me to have a more anxious, nervous, over-imaginative view of the world, expressing itself in fantastic, birdlike, beetlelike forms with a nightmarish quality about them’.18 It was perhaps the birdlike qualities Moore identified in art from Papua New Guinea that led him in to draw a lyre bird in 1936 in the shape of the shield-like object, featuring similar parallel lines down its length, a crescent shaped disc, and a circle near the bottom, which he used to denote the bird’s eye (fig.12).

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture c.1935

Graphite on paper

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture c.1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Square Form Lyre Birds 1936, 1942, 1972

Graphite, chalk (part washed) and felt-tipped pen on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Square Form Lyre Birds 1936, 1942, 1972

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s engagement with ancient and non-Western art while he was designing his upright motives was not limited to this bird motif. In 1965 he noted that he began work on his maquettes ‘by balancing different forms one above the other – with results rather like the North-West American totem poles’.19 An unnamed critic writing in the Burlington Magazine in 1965 suggested that ‘we can find echoes of their monumentality in Scottish early medieval crosses, in Celtic art and even in ancient Assyrian obelisks. Perhaps the days Moore spent in the British Museum thirty-five years before these sculptures were executed left him with some feeling for the grandeur and strangeness of upright stone monoliths’.20 Later that same year Herbert Read supplemented these references, proposing that prototypes for Moore’s standing totems could be found in the prehistoric standing stones of Stonehenge and Avebury Circle in south-west England and Carnac in Brittany, France.21

Moore first visited Stonehenge as a student in autumn 1921 and retained an interest in the Neolithic standing stones throughout his career, culminating in his Stonehenge lithographs of 1972–3 (see Tate P02169– P02187). According to the art historian Andrew Causey, Moore revisited the site on more than one occasion in the 1950s ‘when his daughter, Mary, was at school nearby’.22 As the art historian Sam Smiles has outlined, by the 1930s a number of artists within Moore’s circle had developed an appeal for the standing stones. Modernist artists including Barbara Hepworth and Paul Nash sought to emulate the forms and values of prehistoric Britain which were deemed to be more expressive than the classicism of the European fine art tradition.23 In a letter to Nash written on 15 September 1933 Moore responded to a query stating, ‘Yes. I’ve seen Stonehenge. Its [sic] very impressive. I’ve read somewhere that certain primitive peoples coming across a large block of stone in their wanderings would worship it as a god – which is easy to understand, for there’s a sense of immense power about a large rough-shaped lump of rock or stone’.24 In their essay examining Moore’s outdoor sculptures, art historians Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell suggested that ‘by the later 1930s Moore and Hepworth were clearly ready to suggest that their own sculptures were monuments in a lineage of stone monuments of the Neolithic builders, with perhaps a similarly arcane or forgotten purpose. Their sculptures were at once ancient and modern, or, to use the title of Paul Nash’s painting, Equivalents for the Megaliths’ (see Tate T01251).25

Henry Moore

Stones in a Landscape 1936

Charcoal, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

559 x 381 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Stones in a Landscape 1936

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

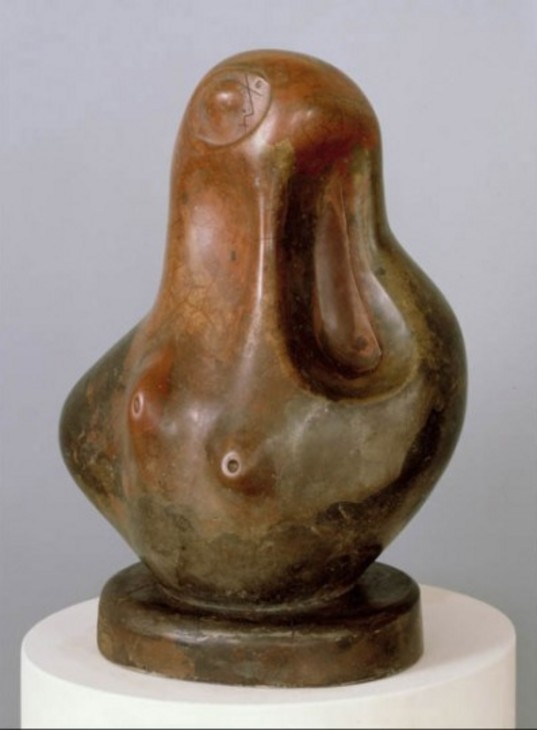

Herbert Read also noted the debt owed by Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross to Moore’s earlier work, stating that ‘the “head” of the Glenkiln Cross has the same blunted cyclopic form as the Composition in carved concrete of 1933 belonging to the British Council or the Corsehill stone Figure of 1933–34’ (fig.14).27 The sculptures identified by Read were made during Moore’s most surrealist phase in the mid-1930s. In his survey of surrealism in Britain, art historian Michel Remy identified Moore as an active member of a group of artists, writers and critics, including Nash, Read and Roland Penrose, who advocated surrealist ideas and motifs during this decade.28 Moore exhibited in a number of surrealist exhibitions throughout the 1930s and Figure 1933–4 and Stones in a Landscape 1936 were displayed in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London. The inclusion of these works define, according to Causey, ‘what Moore thought appropriate for a Surrealist exhibition at this time’.29

Henry Moore

Figure 1933–4

Corsehill stone

Osborne Samuel Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation, All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Figure 1933–4

Osborne Samuel Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation, All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Composition 1933

Concrete

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Composition 1933

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Read’s identification of the upper section of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross as a head suggests that human, figurative forms may be identified within its bulbous shapes. Moore’s concrete Composition 1933 (fig.15) is generally understood as an amorphous portrait bust, with a head morphing out of an armless torso. Although Composition does not represent a human form with any anatomical accuracy, its associative ties to the figurative are supported by Moore, who in 1932 remarked that ‘all the best sculpture I know is both abstract and representational at the same time’.30 Discussing this figurative undercurrent in Moore’s work, in 1968 the critic John Russell suggested that in his upright motives, Moore was grappling with the problem of how to give the ‘human figure the freedom and the audacity and the manifold reverberation of the abstract idiom’.31 As such, he argued that Moore’s upright motives were ‘altered or “perturbed” objects, in the Surrealist sense’.32

Henry Moore

Studies for Standing Figures 1949

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour wash and gouache on paper

590 x 490 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Studies for Standing Figures 1949

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

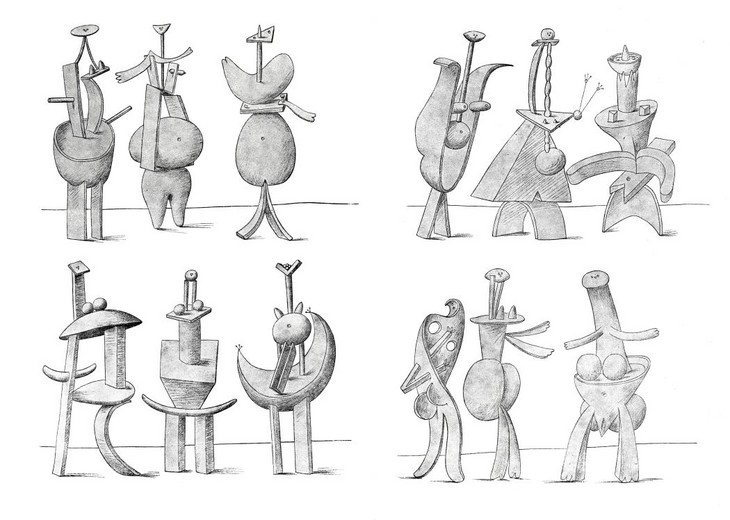

Pablo Picasso

An Anatomy 1933

Reproduced in Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7

Fig.17

Pablo Picasso

An Anatomy 1933

Reproduced in Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s Moore continued to explore the varied compositional possibilities of the standing figure. In drawings such as Studies for Standing Figures 1949 (fig.16) the body is broken down into component parts. This method of fragmenting and reconstructing the figure bears an affinity with drawings published by Pablo Picasso under the title An Anatomy 1933 (fig.17). Moore had been aware of Picasso’s work since his student days at Leeds School of Art, and in 1973 reflected that ‘really all my practicing life was as a student, and as a sculptor I have been very conscious of Picasso because he dominated sculpture and painting – even sculpture as well as painting – since Cubism’.33 An Anatomy was originally reproduced in the first issue of the periodical Minotaure, published in Paris in June 1933, and it is probable that Moore saw or bought a copy around the time of its publication.34 In his drawings Picasso presented the human body as an assemblage of precariously balanced shapes and objects. Arches, prisms and cuboids are stacked with shapes recalling ladders, chairs and cogs, reconfiguring the body as a series of interconnected forms in space. Although Moore preferred rounded forms, rather than the hard-edged shapes found in An Anatomy, the technique of building figures from discrete components was put to productive use in his drawings.

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.2 1955

Bronze

180 x 337 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Darren Chung, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.2 1955

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Darren Chung, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The final work for the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam was constructed in brick and comprised rounded, organic shapes framed by vertical striations on both sides and geometric blocks above and below. According to John Russell, Moore’s relief works were, ‘abstract arrangements that had a formal life of their own: a vigorous, chunky, all-purpose vitality that seemed to burst out of the columnar structure and set off all manner of associations. They were not so much reliefs as free-standing sculptures that seemed to have sunk into the body of the wall’.38 Following a discussion with Moore on 12 December 1980, Tate curator Richard Morphet reported that the Bouwcentrum commission ‘led to the idea of releasing the forms from their incorporation in the fabric of the wall so that they become free-standing’.39

Henry Moore

Maquette for Upright Form c.1954

Plaster

Leeds City Art Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Maquette for Upright Form c.1954

Leeds City Art Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Spiritual themes

Upright Motive No. 1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 installed at Glenkiln, Dumfreisshire

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Henry Moore Foundation archive

Fig.20

Upright Motive No. 1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 installed at Glenkiln, Dumfreisshire

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Henry Moore Foundation archive

In 1956 the first cast of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross was acquired by W.J. Keswick for his estate, Glenkiln, in Dumfriesshire, where two other sculptures by Moore – Standing Figure 1950 and King and Queen 1952–3 (Tate T00228) – were also located.44 According to Keswick’s nephew, John McEwen, Moore decided to make the sculpture after he and Keswick had been for a walk on the estate and saw ‘the distant figure of a shepherd’ appear over the crest of a hill that ‘commanded a view over the whole glen’, which they agreed would make an excellent site for a sculpture.45

Although the resulting work is now known as Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross, McEwan asserts that the original title of the work was simply Glenkiln Cross, and that it acquired its full title later in order to place it within the upright motive series. This assertion is corroborated by the sculpture’s presentation as Glenkiln Cross in a number of exhibitions between 1959 and 1960, including Documenta 2 in Kassel in 1959 and Moore’s solo show at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960. In his review of the outdoor exhibition Sculpture in the Open Air, held in Battersea Park, London, in 1960, which included a cast of the sculpture, the critic Robert Melville noted that ‘it gets its name from Glenkiln Farm at Shawhead in Scotland, where the first cast stands’.46 For McEwan, Glenkiln Cross, as ‘the first Upright Motive’, was ‘indisputably conceived as a single work’.47

In 1960 Moore explained that Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross is ‘meant to be a rudimentary worn-down cross – the cross and the figure on the cross being merged together’.48 Responding to this statement Melville reflected that:

I do not think he really means to imply that he started to make this piece of sculpture with ideas about a crucifixion in mind; I think he is simply telling us what the finished work suggests to him ... I think that if Moore has a kind of crucifixion in mind when working on the Glenkiln Cross the idea would have compelled him to effect a more drastic interpenetration of figure and pillar.49

Moore was not a practising Christian, although he had made religious artworks for Christian settings before, most notably his Madonna and Child 1943–4 for St Matthew’s Church in Northampton, and as his letter of 1933 to Paul Nash revealed, he was aware of the symbolic power of religious imagery.50 In Grohmann’s interpretation of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross he suggested that although the sculpture may not represent Christian imagery, it did possess religious or symbolic power:

there is something swelling about the whole upper half of this ‘Motive’ that is more animal than vegetal ... The observer wavers between animal and man, the sensual and the sublime, but the sublime [is] stronger – how else could the monument dominate the landscape? It dominates in a way in which a Christian cross stands watch over a landscape. In the case of the Christian Cross people know its meaning; not in the case of the ‘Glenkiln Cross’. They feel it to be a local deity and hear the call of Pan, the god of flocks and shepherds, who could strike terror in men, but might also appear as a divine helper. The monument is a symbol of something that exists not something that ought to exist, and is full of disturbing life.51

According to Grohmann, Moore modified the Christian symbol of the crucifix to create a powerful and primal standing form. Although Stonehenge was overlooked by Grohmann, the critic did draw parallels between the sculpture and the Celtic menhirs and Christian standing stones found in Scotland.52 This interpretation was in keeping with contemporaneous scholarship on Moore, which tended to emphasise his interest in ‘primitive’ art and spirituality. For example, in 1958 the critic J.P. Hodin argued that Moore’s work should be understood in relation to the natural landscape, human consciousness and archaic and primitive art.53 That same year Moore himself noted that ‘the great (the continual everlasting) problem (for me) is to combine sculptural form (power) with human sensitivity and meaning, to try and keep the Primitive Power with humanist content’.54 In his conclusion, Grohmann remarked that the individual elements of the sculpture combine in a ‘divine appearance and become spiritual expressions’.55

In his own account of the upright motives Herbert Read located their meaning not in spirituality but in psychology: ‘the formal origins and psychological significance of the Glenkiln Cross and other Upright Motives lie within the gradual unfolding of Moore’s own archetypal vision’.56 Read was an expert on the psychological theories of Carl Jung, who advanced the notion of an archetype as a pervasive idea, image or symbol that forms part of humanity’s collective unconscious. For Read, Moore’s upright motives exist beyond the realm of naturalistic representation or organised religious symbolism, and appeal to a collective human sensibility that is both innate and universal.57 In order to support his assertion Read cited an excerpt of Jung’s 1931 essay, ‘On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry’:

For art is innate in the artist, like an instinct that seizes and makes a tool out of the human being. The thing that in the final analysis wills something in him is not he, the personal man, but the aim of art. As a person he may have caprices and a will and his own aims, bit as an artist he is in a sense “man”, he is the collective man, the carrier and the shaper of the unconsciously active soul of mankind.58

Read explained:

These words of Jung may seen to remove art into the realm of mysticism, but they serve to explain, not only the artist’s own inability to give a rational account of his work, but also the otherwise inexplicable power of that work over other people. Such power is an empirical fact, and we need a hypothesis like Jung’s to explain it – the traditional aesthetics of beauty are inadequate.59

The experience of situating this work and others outside at Glenkiln directly informed Moore’s preference for placing his sculptures in an outdoor environment. In 1968 he reflected that ‘in Scotland I think the single cross is probably better placed: seen from across the moor your attention is drawn towards it as if X marks the spot. From a distance a cross form stands out so much more than any other form’.60 Although Moore’s early supporter Kenneth Clark was initially hostile to the idea of placing his sculptures outside – and not simply outside, but in a natural landscape – Moore nonetheless came to the view that the open sky served as the optimal backdrop for his work. It was perhaps for this reason that he kept photographs of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross, King and Queen 1952–3 and Standing Figure 1950 positioned at Glenkiln pinned to notice boards in his studio. Clark came to agree with Moore, writing in 1977 that ‘the supreme examples of siting Moore’s work are Tony Keswick’s placements of four pieces on his sheep farm at Glenkiln in Dumfriesshire, Scotland ... everyone who sees the works in this setting comes away deeply moved ... The siting of the Glenkiln pieces is what one might call a Wordsworthian use of sculpture’.61

After the first cast was erected at Glenkiln in 1956 other casts of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross were exhibited internationally, most notably in the second Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany, in 1959. Tate’s cast was exhibited in Sculpture in the Open Air in Battersea Park in 1960, where, according to Melville, ‘it stood apart and aloof, estranged by its tallness and its incomparable grandeur’.62 The sculpture was located near works by Reg Butler and Hubert Dalwood, and was framed by trees.63 However, at his solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1960, Tate’s Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross was exhibited between two other sculptures from the series, Upright Motive No.2 and Upright Motive No.7. In his review of the exhibition for the Observer, Nevile Wallis wrote that:

in the Glenkiln Cross, previously seen in Battersea Park, and now flanked by two kindred totems, the sense of organic growth is fused with an architectonic order ... The counterpoint is certainly effective. Yet the weathered, semi-human Celtic cross has greater eloquence for me than the more strictly formalised columns alongside. Moore’s creations are usually most haunting, to my mind, when they are least abstract and their remote grandeur is tempered by his humanity.64

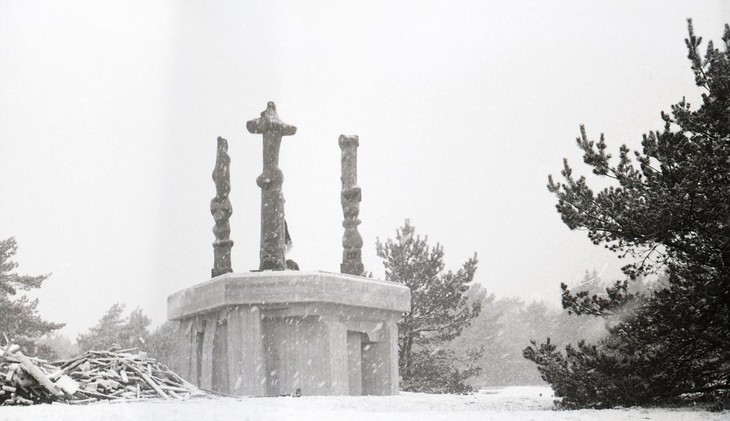

It is likely that Wallis’s response to the configuration of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross alongside two other Upright Motives was coloured by knowledge of the sculpture’s isolated placement at Glenkiln. However, Moore later suggested that the triptych arrangement had been intended from the time of their casting. In 1965 he explained that ‘when I came to carry out some of these maquettes in their final full size, three of them grouped themselves together’. 65

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, 1965

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.21

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, 1965

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s sculptures may also be understood in relation to the engagement of religious themes and subjects by artists working at the same time. In 1965 a critic writing in the Burlington Magazine observed that Moore’s upright motives were created ‘at roughly the same time as Graham Sutherland was experimenting with the same type of figure in his paintings’.71 However, it was not until 1998 that this reference to the British painter Sutherland was explored further. In her book New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society the art historian Margaret Garlake compared Moore’s upright motives with contemporary works by Sutherland, remarking that the triptych of sculptures produced ‘a set of variations on natural forms that were congruent with Christian imagery in a manner comprable to Sutherland’s standing forms’.72 For example, in paintings such as Standing Forms II 1952 (Tate T03113; fig.22), Sutherland depicted three vertical forms comprised of interlocking organic shapes, some of which are positioned on plinths. These associations are strengthened by the fact that Moore knew Sutherland’s work well. Not only was he present at the unveiling of Sutherland’s Crucifixion 1946 at St Matthew’s Church in Northampton (which had also commissioned Moore’s Madonna and Child 1943–4), but he also exhibited alongside Sutherland in the British Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale. In addition to Sutherland, the paintings of Francis Bacon have also been thought to have influenced the forms that appear in Moore’s sculptures in the early to mid-1950s. In the catalogue for Moore’s posthumous exhibition at the Royal Academy, London, in 1988, the curator Susan Compton proposed that the bulbous torsos and truncated limbs of the figures in Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (Tate N06171) may have informed the upper portion of Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross.73 It is probable that Moore viewed Bacon’s painting when it was acquired by Tate in 1953, when Moore was a trustee of the gallery.

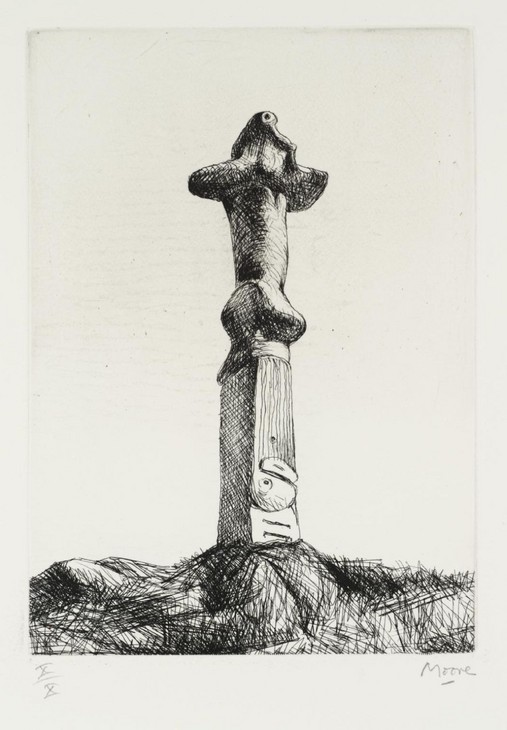

Henry Moore

Glenkiln Cross Plate I 1972–3

Intaglio print on paper

Tate P02163

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.23

Henry Moore

Glenkiln Cross Plate I 1972–3

Tate P02163

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1972 Moore returned to Upright Motive: No.1 Glenkiln Cross, producing two etchings of the sculpture (fig.23). Although Moore had created graphic works on paper throughout his career, he began etching and printmaking with a new level of consistency in the early 1970s. When the Bourne Maquette Studio was built on the grounds of his home in 1970, Moore turned his old maquette studio into a dedicated space for etching and experimented with the medium at length. Examples of the works produced during this period were presented to the Tate by the artist in 1975 (Tate P02163 and P02164).

The Henry Moore Gift

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.24

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 on display in the Duveen Galleries, Tate Gallery, London, 1978

Tate Archives

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Following the exhibition the three upright motive sculptures were returned to Moore. In a letter to Moore’s secretary Betty Tinsley dated 25 July 1978, Ruth Rattenbury, Assistant Keeper of the Collection, itemised a number of works to be returned to the artist for repairs, and of the three upright motives noted that, ‘Mr Moore said that he would have them treated so that they were all the same colour’.77 In May 1979 the sculptures were returned to Tate and installed on a specially designed base on the lawn in front of the gallery. It is evident from the photographs taken of the installation at the time that the sculptures no longer displayed the variations in colour as they had previously (fig.25).

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 installed on the front lawn, Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.25

Upright Motive No.7, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.2 installed on the front lawn, Tate Gallery, London

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, November 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.26

Upright Motive No.7 1955–6, cast c.1958–61, Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60, and Upright Motive No.2 1955–6, cast c.1958–62 installed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, November 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

All three upright motive sculptures in the Tate collection remained on display on the Tate lawn until April 1983 when they were relocated to the nearby Battersea Park. On 26 May Tate was notified that vandals had breached the security fence surrounding the sculptures, which were still in the process of being installed, and had set fire to the protective canvas covering Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross and Upright Motive No.7. As a result the patina and surface of the lower areas of the two sculptures were charred.78 Despite this inauspicious start, the installation of the three upright motives continued as planned, and they were positioned in a prominent position on top of a raised incline. Apart from being removed temporarily for display at the Royal Academy of Arts and at Tate in 1988 and 1992 respectively, the sculptures remained at Battersea Park until October 1994. That month Upright Motive No.2 was forcefully rocked by vandals until it fell over and the decision was made to permanently remove all three of the upright motives from the park. They were subsequently placed on long-term loan to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in Wakefield (fig.26).

The other six bronze casts of the sculpture are held at the Glenkiln Estate, Shawhead; the Sprengel Museum, Hannover; the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; the Folkwang Museum, Essen; and the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth. The full-size original plaster for Upright Motive No. 1: Glenkiln Cross is in the Moore Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. As well as the Kröller-Müller Museum and Tate, the Amon Carter Museum also owns casts of Upright Motive No.2 and Upright Motive No.7. There they are arranged together on a black granite base designed by Philip Johnson, architect of the museum.

Alice Correia

March 2013

Notes

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.160.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.18. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.234.

John Russell in Henry Moore, John Russell and A.M. Hammacher, Drie Staande Motieven, Otterlo 1965, unpaginated.

Moore’s niece, Ann Garrould, who catalogued Moore’s drawings, deciphered Moore’s hand written note as ‘New Ireland | stump’, while the art historian Christa Lichtenstern has read it as ‘New Ireland | string’. See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Complete Drawings 1930–39, London 1998, p.154, and Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, p.205.

In his introduction to the book Moore concluded that, ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Anon., ‘Acquisitions of Works of Art by Museums and Galleries: Supplement’, Burlington Magazine, vol.107, no.747, June 1965, p.338.

Sam Smiles, ‘Equivalents for the Megaliths: Prehistory and English Culture, 1920–50’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven 2002, pp.199–223.

Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell, ‘Henry Moore and the Post-War British Landscape: Monuments Ancient and Modern’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.138.

Henry Moore cited in Arnold Haskell, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

Henry Moore, ‘Interview with Elizabeth Blunt’, Kaleidoscope, radio programme, broadcast BBC Radio 4, 9 April 1973, transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.167.

See Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7. For further discussion on Moore’s familiarity with French periodicals, including Minotaure, see Julia Kelly, ‘The Unfamiliar Figure: Henry Moore in French Periodicals of the 1930s’, in Beckett and Russell 2003, pp.43–65. See also Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, pp.130–49.

The centre was demolished in 2010 and Moore’s Wall Relief No.1 was put into storage by the city of Rotterdam. See http://www.arttube.nl/en/video/CBK_Rotterdam/Henry_Moore , accessed 28 January 2014.

Anita Feldman Bennet, ‘Rediscovering Humanism’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.69.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2281, Three Motives Against Wall No.2’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.126.

See, for example, Grohmann 1960, p.197, and Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.7.

Peyton Skipwith, ‘Abstract Sculpture and Modern Architecture’, in Henry Moore and Michael Rosenauer, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1988, unpaginated.

In 1973 Moore stated that, ‘Although I was baptised and made to go to church as a boy, I am not a practicing Christian’. Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.269.

Christa Lichtenstern later expanded upon the relationship between Celtic crosses and Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross. See Lichtenstern 2008, p.206.

Kenneth Clark, ‘Foreword’, in David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977, p.20.

Anon., ‘Acquisitions of Works of Art by Museums and Galleries: Supplement’, Burlington Magazine, vol.107, no.747, June 1965, p.338.

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.191.

These figures are based on those listed in a memo in the records for the exhibition. See Tate Public Records TG 92/344/2.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6, cast 1958–60 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www