Henry Moore OM, CH Mask 1929

Image 1 of 11

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask 1929© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Mask

1929

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

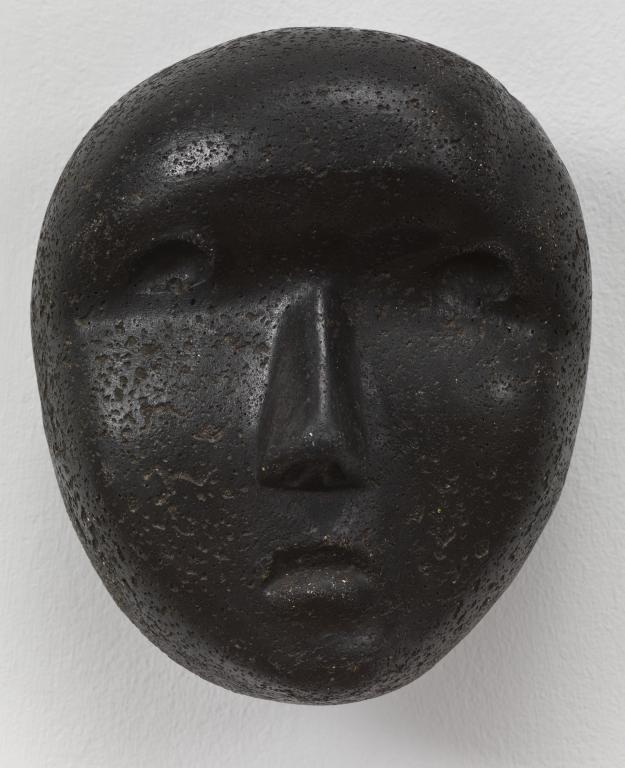

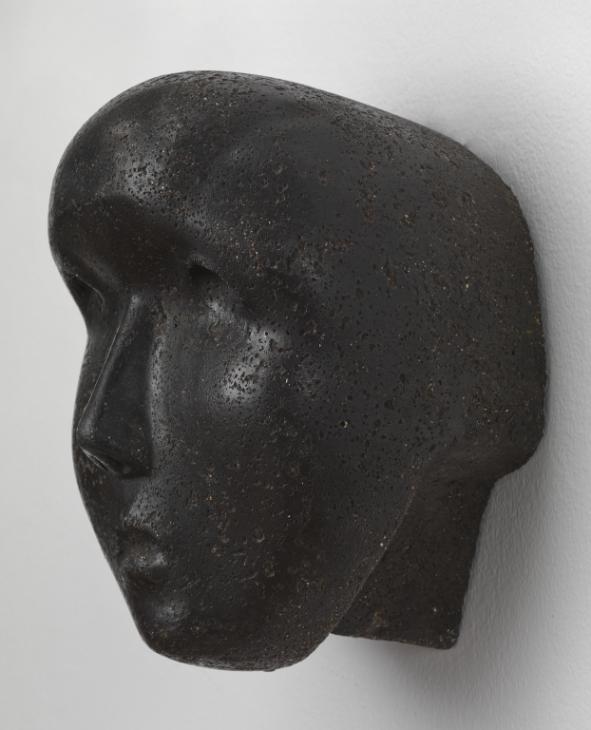

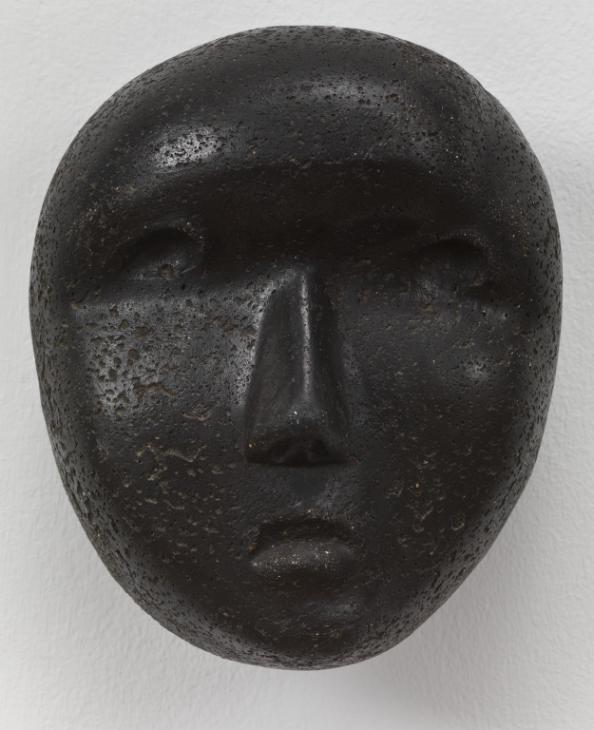

This is one of three mask sculptures cast in concrete by Henry Moore in 1929. It is an example of the artist’s engagement with unconventional sculptural materials and points to his interest in non-Western art.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Mask

1929

Cast concrete

200 x 180 x 130 mm

Presented by Mr Henry Bergen to the Victoria and Albert Museum 1949; transferred to the Tate Gallery 1983

T03762

Mask

1929

Cast concrete

200 x 180 x 130 mm

Presented by Mr Henry Bergen to the Victoria and Albert Museum 1949; transferred to the Tate Gallery 1983

T03762

Ownership history

Acquired by Mr Henry Bergen probably before 1944 by whom presented to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1949; transferred to the Tate Gallery 1983.

Exhibition history

1931

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London, April 1931, no.24 (as ‘Mask No.3’).

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th-Century British Sculpture from Tate, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, July–September 2001, no.7.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.10.

2006

Henry Moore, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona, July–October 2006, no number.

2007

Art Now: Goshka Macuga, Tate Britain, London, June–October 2007, no number.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no number.

References

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pl.61a (noting private ownership).

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, no.63 (noting private ownership).

1984

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’, in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, pp.595–614.

1988

[Judith Collins], ‘Mask 1929’, The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84, London 1988, pp.540–1.

1988

Penelope Curtis, Modern British Sculpture from the Collection, display catalogue, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool 1988, reproduced p.43 (as Head 1928).

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th-Century British Sculpture from Tate, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich 2001, p.16.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.40.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006, reproduced p.71.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, no number.

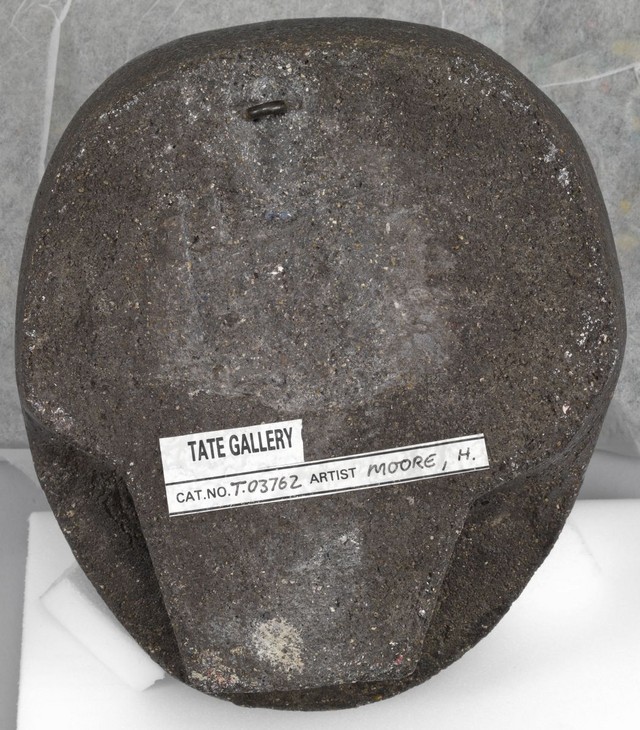

Technique and condition

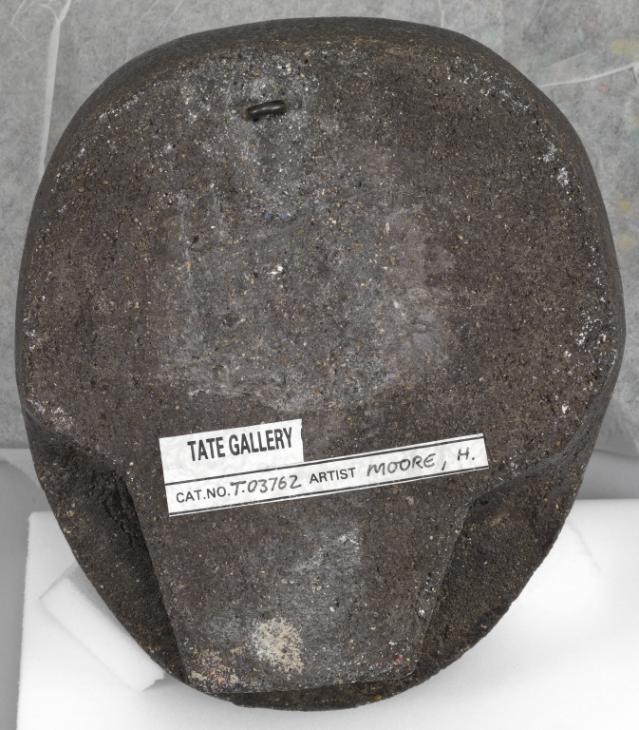

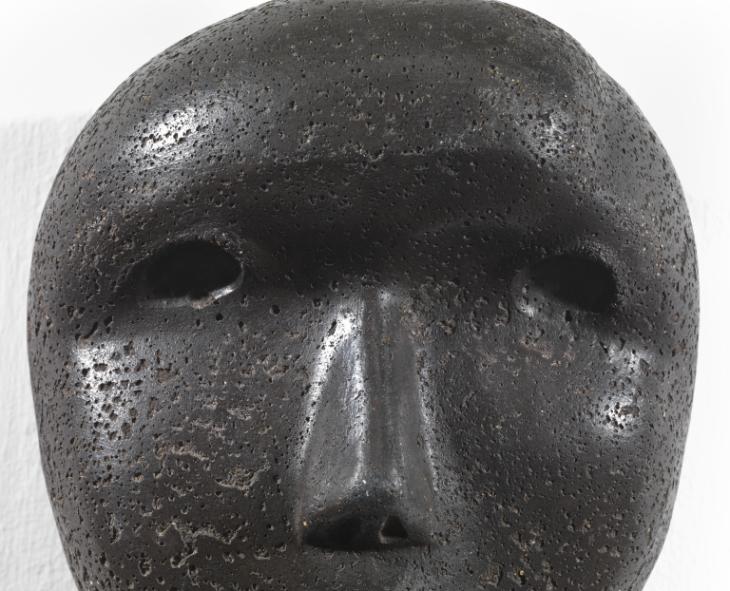

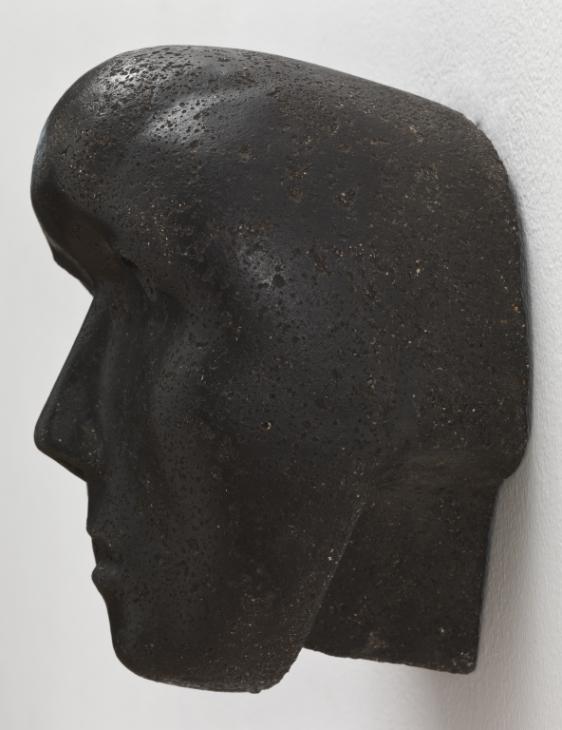

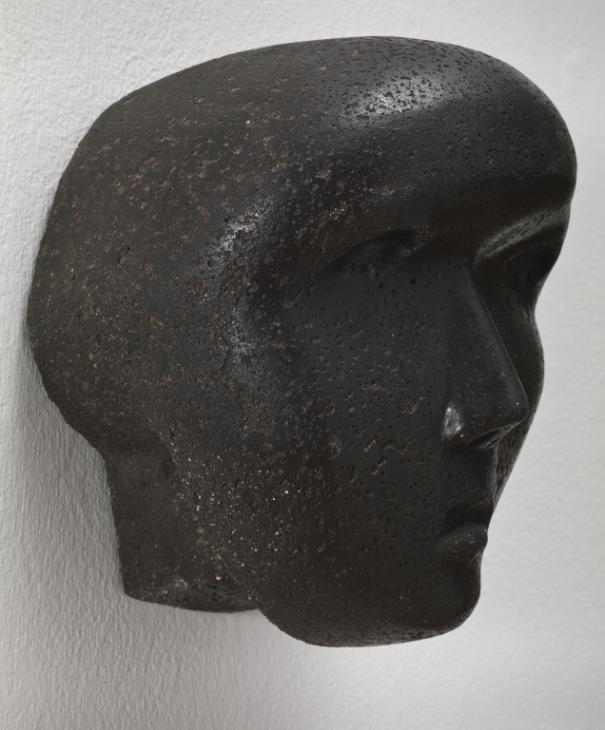

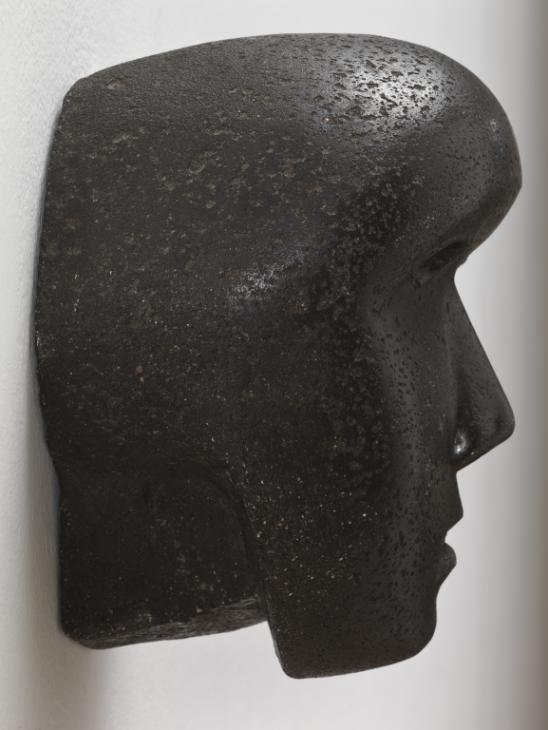

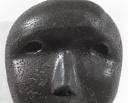

This is a small, wall-hung sculpture of a human face cast from cement mixed with an aggregate. The cement is a very dark grey colour and it is possible that Moore may have added pigments to the mix to colour it. The surface of the cast is smooth and shiny. Texture is provided by the numerous shallow pockmarks caused by scattered bubbles and air pockets during the casting process. The fine surface finish has been produced by direct casting in a mould taken from an original model made by Moore, probably from clay or plaster, which was then carefully sanded using fine abrasives. The only evidence of any tool marks made after casting is on the lower lip where it may have been necessary for Moore to correct a small flaw (fig.1). It is likely that the surface has been further enhanced by the application of a little wax. There is no inscription on the cast.

There is a sharp edge around the chin, and behind this the form has been narrowed to a square edged ‘neck’ shape. The back of the mask is flat but a wide shallow depression has been hollowed out, perhaps with a chisel, underneath the fixing at the top. The fixing itself is a U-shaped steel rod that has been embedded to form a loop (fig.2). Initially, this may have been embedded a little too deeply and the area around it has subsequently been hollowed out to ensure that it can provide a secure fixing.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Mask 1929 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

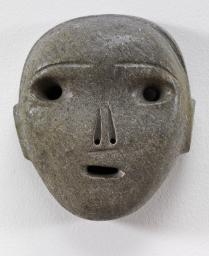

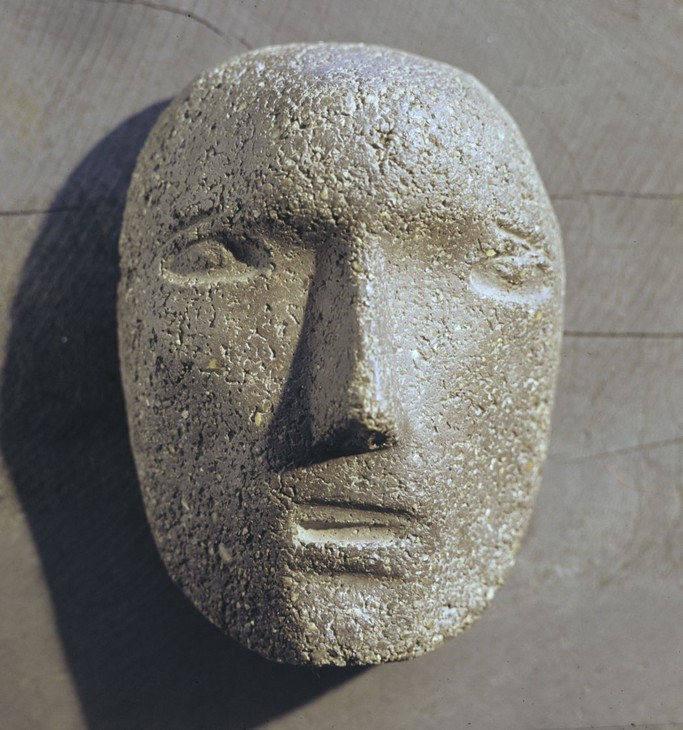

Mask is a small, wall-mounted sculpture of a schematic human face. Although its title declares it to be a mask, this sculpture was not designed to be worn. The sculpture is oval in shape, with the chin only slightly narrower than the forehead. The sides of the face are quite deep so that the sculpture projects away from the wall. The face has a very prominent brow, which overhangs the eyes and nose of the sculpture and when seen from the side seems to project upwards. The two eyes are equally spaced and are represented by two depressions. The upturned nose creates a ridgeline down the centre of the face and takes the form of a tetrahedron. Two triangulated nostrils indent the base of the nose. Like the rounded forehead, curved cheekbones contrast with the angular shape of the nose. The mouth is narrow and downturned. The upper lip has been denoted by an indentation while the lower lip is a slightly bulbous protrusion. There are no incised lines to indicate the outline of eyebrows, eyes or lips and when seen from the front the face is dominated by the smooth empty spaces of the cheeks. Ears have not been demarcated. Although seemingly balanced, on closer inspection the facial features of Mask have been presented asymmetrically; the right eye is slightly higher than the left, while the left eyebrow is slightly peaked. The right side of the mouth is turned down slightly.

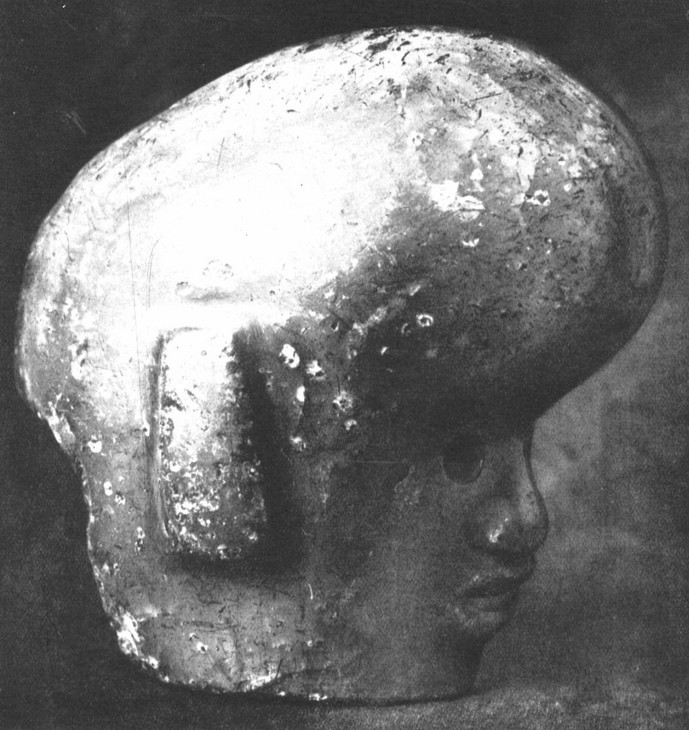

Henry Moore

Mask 1927

Cast concrete

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Mask 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

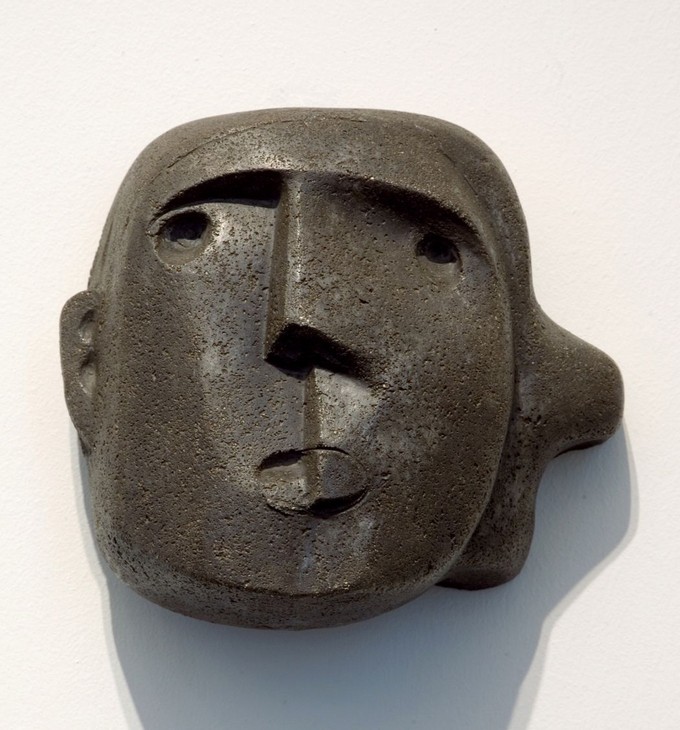

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Cast concrete

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Cast concrete

240 x 210 x 123 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Leeds Museums and Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture was exhibited at Moore’s second solo exhibition in April 1931 at the Leicester Galleries in London under the title Mask (Concrete) No.3. Collins accounted for this title by noting that by 1931 Moore had made four masks in cast concrete, and that this work may have been the third to have been executed.4 The first concrete mask was made in 1927 (fig.1), while the three subsequent sculptures, including Tate’s example, all date from 1929. Although the exact sequence in which the three 1929 sculptures were made is not known, they share certain characteristics: the colour of the concrete, the grained texture of the surface, and the sharp, triangulated nose of Mask (fig.2) are similar to those of Mask, while the pressed eye sockets and down-turned mouth can also be found in Mask (fig.3).

Although Moore’s early published statements on sculpture such as ‘A View on Sculpture’ (1930) and ‘Statement for Unit One’ (1933) prioritised the practice of direct carving and championed the use of stone and wood in sculpture, his use of concrete demonstrates that Moore was not averse to experimenting with unconventional materials early in his career.5 The curator Terry Friedman has highlighted Moore’s innovative use of pigment in his concrete sculptures.6 For Mask Moore used a dark grey pigment which, in combination with the surface texture, gives it the appearance of basalt. Friedman has suggested that by adding pigment to the wet concrete mixture Moore was able to produce sculptures with ‘a decisively unclassical look’, which helped to distinguish his work ‘from the unblemished whiteness of marble so beloved by his hidebound contemporaries’.7 Moore was also concerned about the resilience of his concrete sculptures. In a letter to the collector Michael Sadler, who had acquired a concrete reclining figure which he displayed outside, Moore suggested applying a protective ‘preparation’ – a chemical solution – to the work; from their correspondence it is evident that Moore and Sadler were concerned about weathering, and Moore acknowledged that ‘nobody yet knows enough about the durability of concrete’.8

Moore’s experimentation with concrete at this time may have been prompted by his commission in 1928 to create The West Wind, a relief sculpture for the new London Underground building in St James’s. Reflecting on his concrete mask sculptures in 1968, Moore noted that at the time ‘reinforced concrete was the new material for architecture’ and that he had thought he ‘ought to learn about the use of concrete for sculpture in case I ever wanted to connect a piece of sculpture with a concrete building’.9 Having completed his first architectural commission in late 1928, Moore would have been conscious of the types of commercial and public commissions available to sculptors. His experiments with concrete in 1929 may therefore have been devised as a way to demonstrate to prospective clients his ability to work with architectural materials.

Early on in his artistic career Moore had rejected the traditions of classical art, characterised by anatomical accuracy and technical virtuosity, which had dominated his academic training. When Moore began his course at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1921 the teaching of sculpture focused almost entirely on figuration, and was concerned above all with the styles and techniques of ancient Greek and Roman statuary and Italian Renaissance sculpture. Under the leadership of Professor Francis Derwent Wood (1871–1926), a member of the Royal Academy, students in the RCA Sculpture Department were taught how to copy classical sculptures by accurately modelling replicas in clay or plaster before using a pointing machine to create a white marble copy.10 In this way they would gain training not only in traditional sculpting techniques and materials, but also in the styles and subjects of European art of the past.11 By experimenting with coloured or pigmented materials, which also produced different textures, Moore chose to move away from academic sculptural conventions, positioning himself against naturalistic sculpture using traditional materials and techniques.

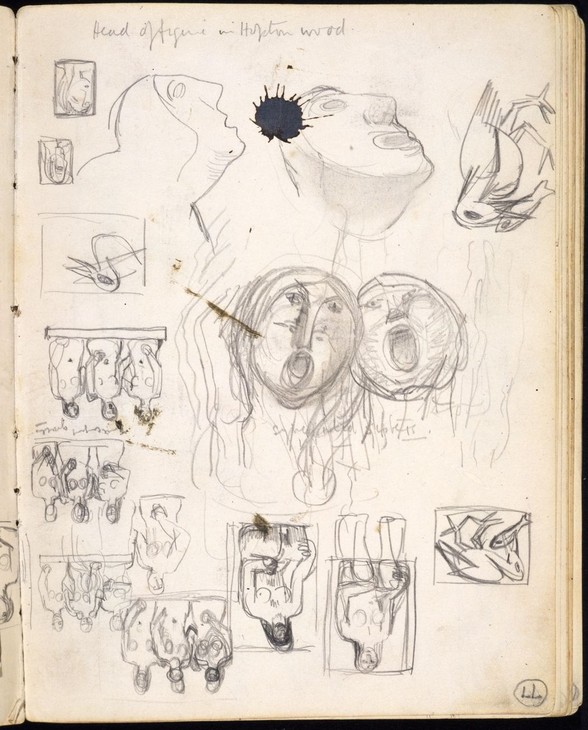

There are no recorded statements by Moore specifically about Mask and it has received very little critical attention to date. However, it has been considered in relation to general discussions about Moore’s masks from the late 1920s. Scholars agree that the impetus behind the production of masks in this period came from Moore’s interest in pre-Columbian art from Central and South America, particularly ancient Aztec sculpture.12 Pre-Columbian art provided inspiration for a number of Moore’s sculptures during the 1920s, such as Head of Serpent 1927 (Tate L01766), which relates to Moore’s study of Aztec snakes.13 The art historian Barbara Braun has noted that throughout the 1920s there was a growth in exhibitions, publications and public interest in ancient Mexican and pre-Columbian, South American art, fuelled by numerous archaeological discoveries.14 These included the 1926 archaeological excavations of an ancient Mayan city in British Honduras (present-day Belize) led by the British Museum’s ethnographic curator T.A. Joyce. These excavations were widely reported in publications such as the Times and the London Illustrated News, and Moore was one of a number of British artists and writers including Leon Underwood (1890–1975) and D.H. Lawrence (1885–1930) who were looking to the arts and culture of ancient Mexico for inspiration.15

This concentration on the arts of ancient Mexico can be understood within the broader artistic tendency known as ‘primitivism’. This is an over-arching term used by art historians to describe a propensity of early twentieth-century European art to emulate the forms and perceived values of non-Western art. The art of so-called primitive cultures – which included tribal art from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as prehistoric and medieval European art – was admired for its apparently direct expression and ability to convey emotion through the schematic use of shape. Moore’s interest in ancient non-Western art dates from his time as a student at Leeds School of Art, where, in 1920, he read the art critic Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920), which included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts. Fry highlighted that ‘more recently we have come to recognise the beauty of Aztec and Mayan sculpture, and some of our modern artists have even gone to them for inspiration’.16 By looking to non-Western artistic sources, artists found ways to challenge the predominance of classical artistic conventions at the turn of the century. As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry and many others, the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.17

Henry Moore

Figure Studies and Heads 1926

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Figure Studies and Heads 1926

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Crouching hunchback from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.2

Fig.5

Crouching hunchback from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.2

Crouching hunchback from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.3

Fig.6

Crouching hunchback from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.3

Deformed head from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

Reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.22

Fig.7

Deformed head from Mexico, undated

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

Reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.22

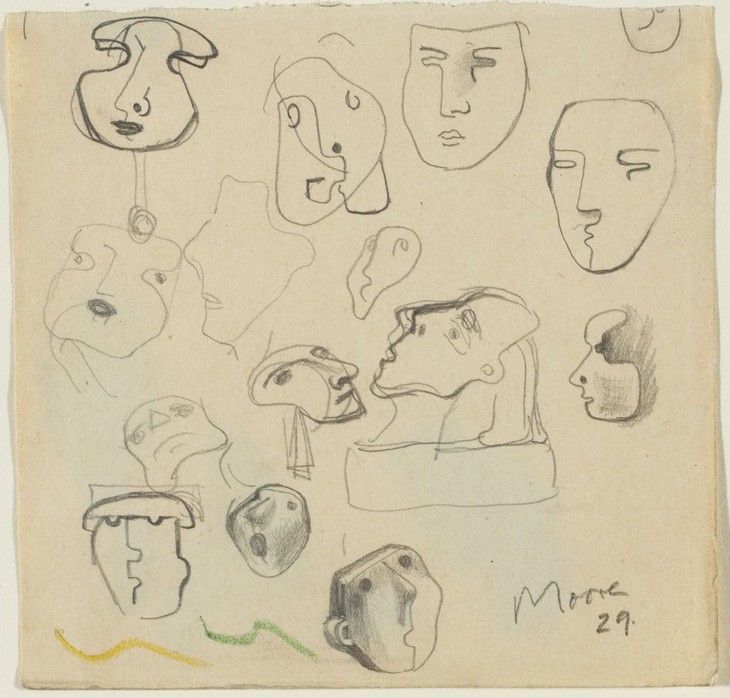

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1929

Graphite on paper

133 x 140 mm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1929

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Mask (side view) 1928

Green gneiss stone

212 x 190 x 87 mm

Tate T06696

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Mask (side view) 1928

Tate T06696

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Wooden stool in the form of a kneeling woman, from Buli, Zaire, c.1900

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.10

Wooden stool in the form of a kneeling woman, from Buli, Zaire, c.1900

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

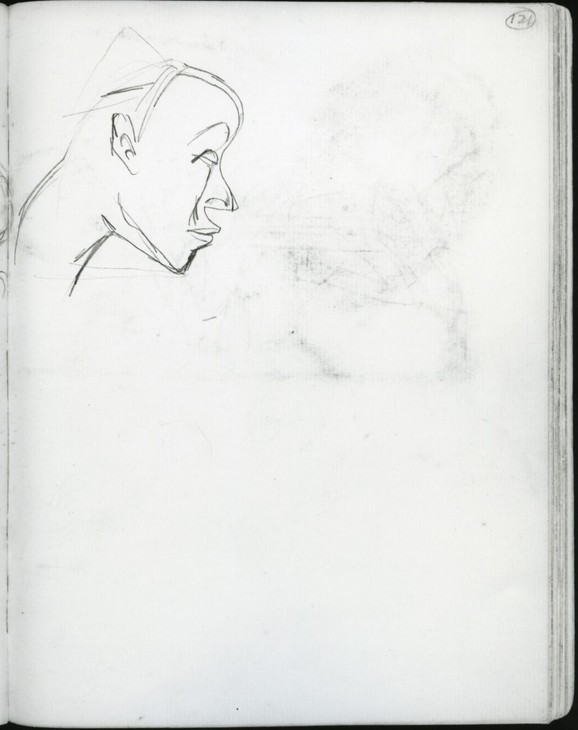

Henry Moore

Study of Head (detail from Notebook No.3) 1922–4

Graphite on paper

224 x 172 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Study of Head (detail from Notebook No.3) 1922–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In 1981 the Zaire stool was included in the publication Henry Moore at the British Museum (1981), for which Moore was invited to select artworks from the British Museum’s collection that had influenced him during his career. In the book Moore stated that the kneeling woman ‘has more vitality and expression than a realistic figure would have. Look especially at the marvellous face, what an impression of stoicism and endurance it gives’.26 While in later work Moore moved away from representing individual facial expressions in favour of more universal archetypes, it is clear that at this moment in the late 1920s he was interested in the face as the locus of identity. Indeed, in 1967 Moore accounted for the asymmetry in his masks, stating:

I used the asymmetrical principle in which one eye is quite different from the other, and the mouth is at an angle bringing back the balance ... I began to find it in reality in all faces ... it is when you come to look at a person’s face with acute observation that you will find these many small variations that make all the difference between a really sensitive portrait and a dull one.27

Moore’s emphasis on how shape and composition rather than naturalistic representation can convey emotion may serve to explain why the facial features of Moore’s masks are at once schematic yet individually distinctive.

Hoa Hakananai'a from Orongo, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), Polynesia, c.1000

Basalt

2420 x 1000 x 550 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.12

Hoa Hakananai'a from Orongo, Easter Island (Rapa Nui), Polynesia, c.1000

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Mask was included in Moore’s second solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London in April 1931. Most reviews were mixed, with some, such as the unnamed critic for the Sheffield Independent, noting that Moore’s sculpture had ‘already aroused some criticism as ultra modern’.29 The unnamed critic for the Star noted the range of materials in which Moore worked, and suggested that ‘some of the concretes demonstrate that the sculptor would have made his fortune as an art faker, for they have that weather-beaten, slightly decayed, rakish look of ancient sculptures dug up from Egyptian tombs, or found in the caves of Central America’.30 While the reviewer for the Star saw Moore’s affinities with ancient sculpture with bemusement, the critic for the Morning Post argued that ‘the cult of ugliness triumphs at the hands of Mr. Moore’ and lamented the waning influence of the classical Greek Elgin Marbles in the British Museum.31 However, more important for Moore and his burgeoning career than these reviews was the fact that the prominent British sculptor Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) wrote a prefatory note for the exhibition catalogue. Epstein concluded that ‘for the future of sculpture in England Henry Moore is vitally important’.32

In Moore’s 1944 monograph edited by the critic Herbert Read, Mask is cited as belonging to a private collector. Although it is unclear when Mask entered his collection, in 1949, Henry Bergen (1873–1950), who lived at 66 Sutton Court in west London, donated the sculpture, along with a drawing by Moore titled Reclining Nude 1930, to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.33 Bergen was an American scholar who had moved to the UK to study early English literature under the auspices of the Carnegie Institution. During the 1920s he edited John Lydgate’s four volume poem Fall of Princes for the Early English Text Society.34 Bergen was also an amateur potter and an enthusiastic collector of Japanese and Chinese ceramics and was noted as owning an important collection of pottery used in Japanese tea ceremonies. He was particularly close friends with the British studio ceramists William Staite Murray (1881–1962) and Bernard Leach (1887–1979), both of whom were known to Moore. Correspondence held in the Bernard Leach Archive reveals that Bergen was also acquainted with Henry Moore and his wife; in a letter dated 26 January 1936 Bergen informs Leach that he has ‘been to the Chinese [ceramics] exhibition [at the Victoria and Albert Museum] 6 or 7 times and am going again next Wednesday with Henry and Irina Moore’.35 In fact it would seem that Bergen and Moore belonged to the same circle of friends; in a letter sent to Moore in 1975 Leach recounts a discussion with Moore at Bergen’s flat in Hammersmith ‘not so long after the war’.36

Also among the correspondence held in the Bernard Leach Archive is a letter tentatively dated 1948 stating that Bergen had suffered a slight stroke and had decided to bequeath his collection of artworks and ceramics to various public collections.37 In 1949, the year before his death, Bergen donated not only Henry Moore’s Mask and drawing, but also a selection of eighteenth-century American furniture and Turkish rugs to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A).

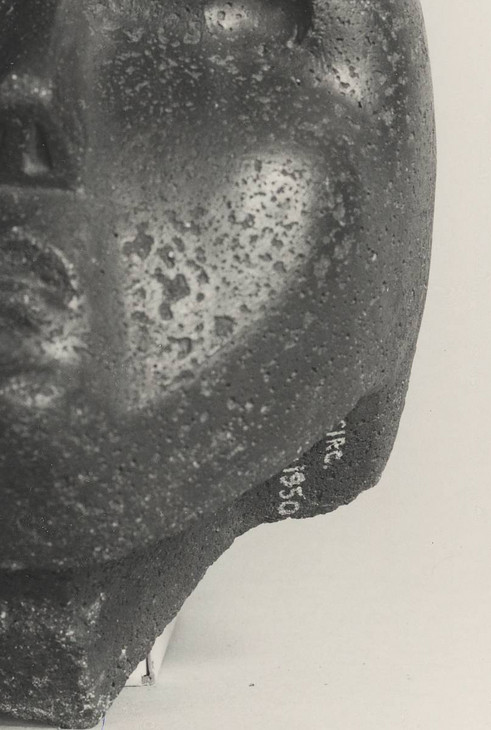

Detail of Mask 1929 showing V&A acquisition number (since removed)

Tate T03762

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Detail of Mask 1929 showing V&A acquisition number (since removed)

Tate T03762

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When it was held in the V&A this sculpture was known as Head 1928, but research undertaken during the 1950s for the revised and expanded fourth edition of Moore’s catalogue raisonné published in 1957 identified it as Mask 1929, as it is now known. In 1983 Mask was one of seventy twentieth-century sculptures transferred from the V&A to the Tate Gallery. The transfer was made in order to rationalise the collections of both institutions, and was reciprocated by the Tate, which transferred to the V&A six of the earliest sculptures in its collection. When Mask entered the Tate collection its acquisition inscription from the V&A, ‘CIRC. | 11–1950’, which was written in white ink on the outer right edge of the sculpture (fig.13), was noted and then erased.

Alice Correia

December 2012

Notes

[Judith Collins], ‘Mask 1929’, The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84, London 1988, p.541.

Henry Moore, ‘A View on Sculpture’, Architectural Association Journal, May 1930, p.408; Henry Moore, ‘Statement’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1933, p.29–30. Both texts are reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, pp.187–8 and 191–3.

A pointing machine is a measuring tool used by sculptors to make like-for-like copies of sculptures. The device comprises a collection of adjustable rods on an armature that are used to measure specific points on the surface of modelled sculpture. The tool measures the width, height and depth of these points from a chosen position and these dimensions are then used to accurately carve into a block of stone or wood. Each time a point (or measurement) is taken, a small hole is drilled into the corresponding block of stone to indicate the point to which the sculptor should carve. The first point of reference is the highest relief point; on a sculpture of a head this might be a protruding nose. This ensures that the sculptor does not carve away too much material. Carvings made with the use of a pointing machine are often pockmarked, where the point has been drilled fractionally too deep. For an example of a sculpture made with a pointing machine with visible point marks see Auguste Rodin, The Kiss 1901–4 (Tate N06228).

Ian Dejardin, ‘Catalogue’, in Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, p.37.

For example see Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.72; Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, p.62; Andrew Causey, The Drawings of Henry Moore, London 2010, p.34. In the 2010 Moore exhibition held at Tate Britain, Mask was displayed in the room titled ‘World Cultures’; see http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/henry-moore-0/henry-moore-room-guide/henry-moore-room-guide-room-1 , accessed 22 November 2012. The term pre-Coloumbian denotes the period of history preceeding Christopher Columbus’s voyages to South America in 1492 and European contact with and influence on American indigenous cultures and civilisations.

For reports on these excavations see Anon., ‘Ruins in British Honduras’, Times, 12 January 1926, p.11, and Anon., ‘More Mayan Ruins Discovered’, Times, 10 February 1926, p.13.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.45.

Alfred P. Maudslay specialised in the study of ancient Mayan inscriptions and his collection of Mayan sculptures had been kept in the basement of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, until ethnographic curator Thomas Joyce transferred it to the British Museum and dedicated a room in the museum for its display. See Braun 2000, p.95.

Henry Moore, ‘Mexican Sculpture’, c.1925–6, Henry Moore Foundation Archive, published in Wilkinson 2002, p.97.

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.68.

Henry Moore, ‘Foreword’, in Primitive African Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Galleries, London 1933, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.99.

Jacob Epstein, ‘A Note on the Sculpture of Henry Moore’, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London 1931, p.6.

See Victoria and Albert Museum Archive RP–49–3191. The Alumni Directory of Yale University published in 1920 lists Henry Bergen among its graduates of 1895. Bergen lived at 55 Sutton Court, Chiswick, London, between 1924 and 1936, and at 66 Sutton Court from 1937 to 1949.

Henry Bergen, letter to Bernard Leach, Bernard Leach Archive, Crafts Study Centre, Farnham, Surrey, item LA.2409, http://www.vads.ac.uk/large.php?uid=66164&sos=10 , accessed 30 July 2012.

See Hettie Wiles, letter to Bernard Leach, Bernard Leach Archive, Crafts Study Centre, Farnham, Surrey, no.12090, in which Wiles notes Bergen’s decision to ‘give all his pots away’. http://www.csc.ucreative.ac.uk/media/pdf/o/p/Bernard_Leach_Catalogue_Volume_II.pdf , accessed 30 July 2012. On 15–16 July 1948 Hodgsons auction house in London held a sale of Bergen’s book collection (see auction notice in the Times, 12 July 1948, p.10) and the same year he gave his large collection of studio pottery, including examples of his own work, to the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent. See http://www.stokemuseums.org.uk/collections/browse_collections/ceramics/studio_pottery/henry_bergen?tab=info , accessed 19 December 2012.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Concrete: Cast, Carved, Coloured and Reinforced Judith Collins

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Mask 1929 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www