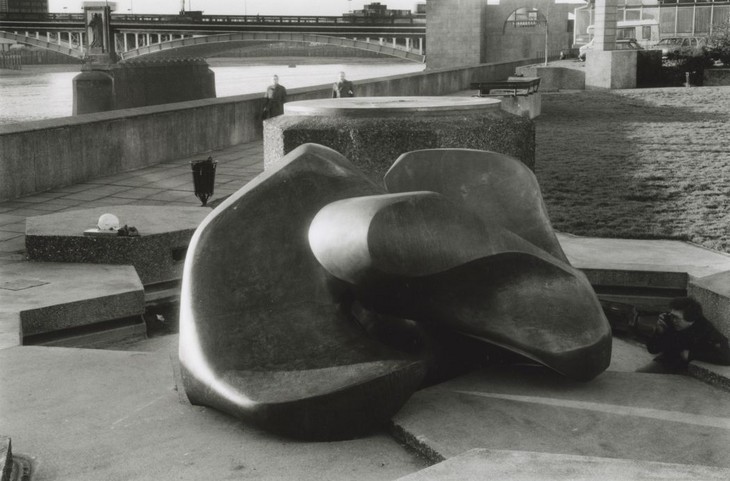

Henry Moore OM, CH Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Locking Piece 1963-4, cast c.1964-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Locking Piece

1963-4, cast c.1964-7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

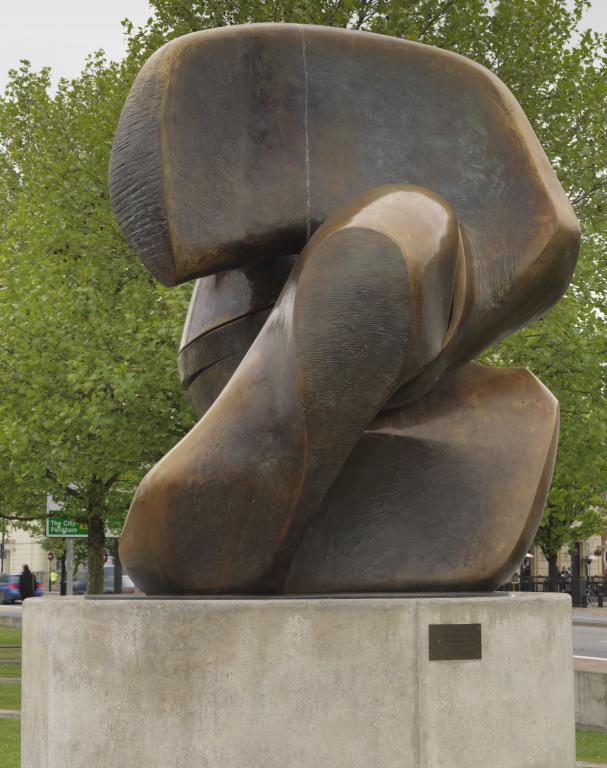

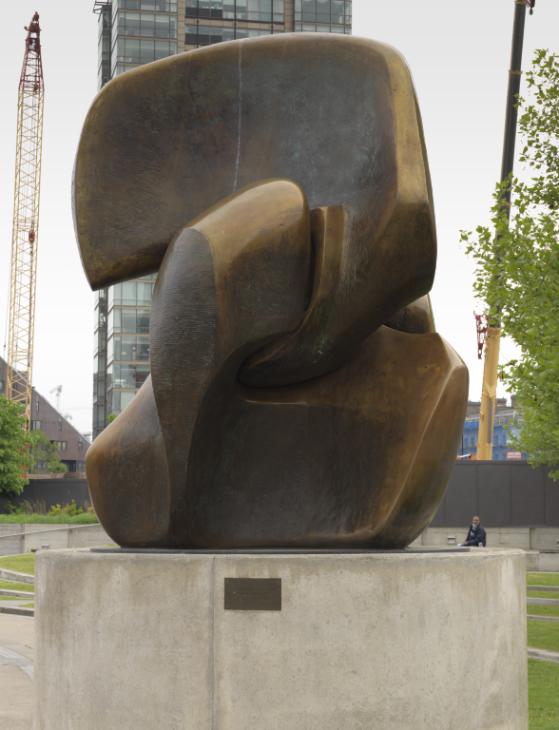

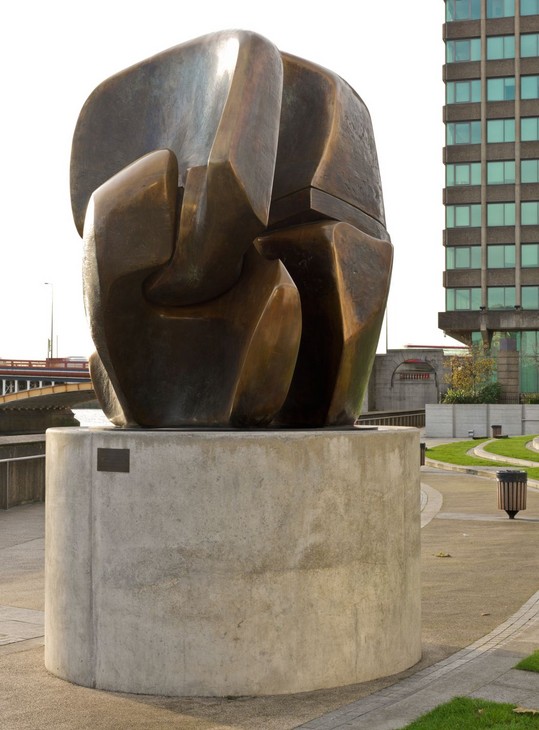

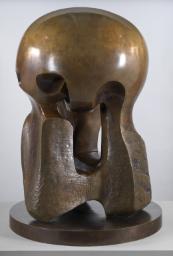

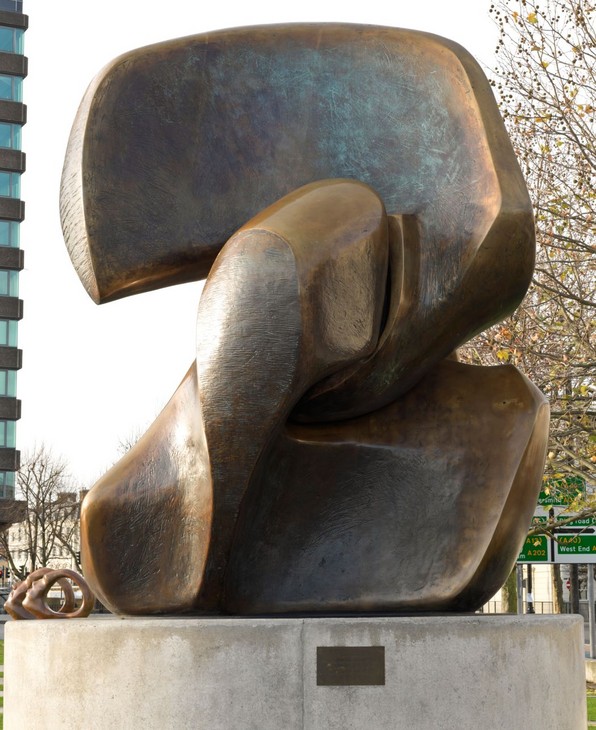

This large abstract bronze sculpture exemplifies Henry Moore’s interest in interlocking forms and the relationships established between different parts of a sculpture, particularly when experienced in the round. The forms of Locking Piece were based on bone fragments and lend the sculpture an organic quality that recalls the artist’s biomorphic work of the 1930s.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Locking Piece

1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Bronze on concrete plinth

2934 x 2800 x 2300 mm

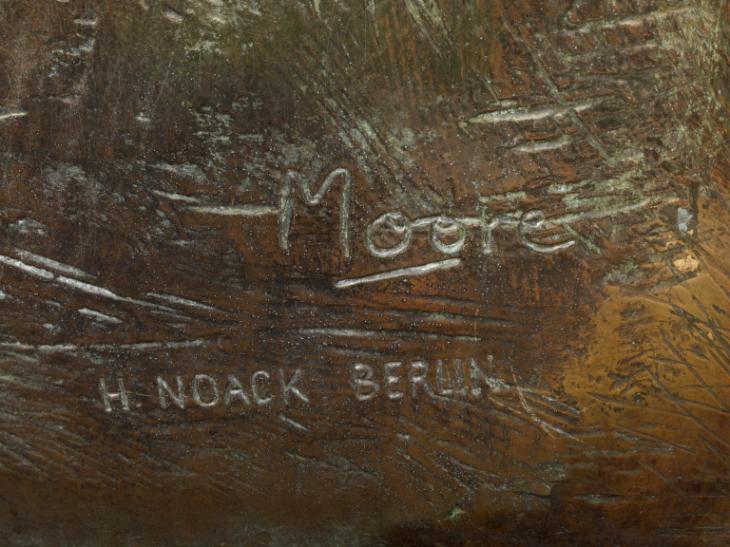

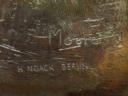

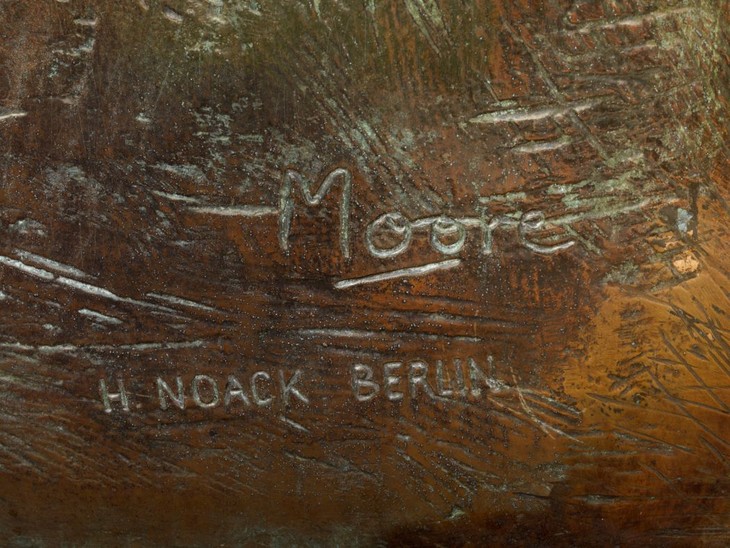

Inscribed ‘Moore’ and stamped ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 3

T02293

Locking Piece

1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Bronze on concrete plinth

2934 x 2800 x 2300 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ and stamped ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 3

T02293

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1967

British Pavilion, Montreal Expo, Montreal, April–October 1967.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

References

1963

Henry Moore: Recent Work, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1963 (Working Model for Locking Piece 1962 reproduced no.15).

1963

Bryan Robertson, ‘Moore and Bacon’, Listener, 25 July 1963, pp.127–8.

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986 (?another cast reproduced pls.173, 174).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.232–4, reproduced pl.236.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.25, 144.

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966, pp.3–23.

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, 1968 London, pp.455–6 (?another cast reproduced pp.454–4).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.141 (original plaster reproduced pl.131 and details pls.127, 134).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.32, pls.681–2.

1973

Henry Moore, ‘On Sculpture and Architecture’, Leonardo, vol.6, no.3, Summer 1973, pp.243–6.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, reproduced pl.137.

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, pp.8–11, 17.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977, p.220.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.52.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.183.

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.134, reproduced p.134.

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, 2nd edn, London 2003, pp.359–60.

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.276–7.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, reproduced p.75.

2007

Derek Pullen and Jackie Heuman, ‘Modern and Contemporary Outdoor Sculpture Conservation – Challenges and Advantages’, Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, vol.22, 2007, pp.4–9.

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, reproduced p.178.

Technique and condition

This is a two-part bronze sculpture comprised of interlocking forms mounted on a shallow circular bronze base fixed to a cylindrical concrete plinth. It is attached to the base and plinth with bolts that run through its underside.

Moore made the original model for this sculpture in plaster, which was used to make the mould from which the bronze was cast. The model was made by applying successive layers of plaster to a supportive armature, which was probably constructed from lengths of wood. The texture of the plaster was replicated in the surface of the bronze, which reveals that Moore used various tools to exploit the properties of the plaster as it dried. Deep striations would have been made with sharp tools while the plaster was still slightly wet, whereas the smooth finish of the high points was creating by filing and sanding the plaster after it had hardened (fig.1).

Detail of Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 showing surface textures

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 showing surface textures

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of welding seam on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of welding seam on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bronze was sand cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin. The maximum size of a cast piece of bronze is determined by the size of the crucible used at the foundry, for bronze must be cast in a single pour. To cast this monumental sculpture the plaster original had to be cut up into approximately fifty pieces, which were cast separately and subsequently welded together. The walls of the bronze are approximately 6 mm thick and it weighs 1800 kilograms. After it was assembled the welds were filed down and textured to integrate them with the surrounding surface, a process known as ‘chasing’. However, welding seams remain visible on the surface of the sculpture along with rectangular patches where faults in the cast have been repaired (fig.2). Once the various parts of the sculpture had been assembled abrasives were applied to the bronze to remove casting residues and to produce a reflective, polished surface.

The surface of the bronze was coloured with an artificial patina. This was achieved by applying chemical solutions to the surface of the bronze, which triggered a reaction that produced coloured compounds. A number of different chemical solutions were used to patinate Locking Piece (fig.3). Its slightly transparent, brown-black hues may have been produced using chemicals such as potassium or ammonium polysulphide, while the warmer orange-brown tones were probably created by applying ferric nitrate. There is also some evidence of an overlying green patina on the inside surfaces. The patina was probably rubbed back at the sculpture’s high points before diluted patination chemicals were applied to the exposed surfaces to produce their polished, almost golden appearance. Brightly finished bronzes can quickly become dull in an outdoor environment, and so the surface was then coated with lacquer to protect its range of colours. After some years of outdoor display the lacquer coat began to break down and was replaced in 1980.

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 blown off its base in 1990

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 blown off its base in 1990

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of artist's signature and foundry stamp on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In January 1990 the sculpture was blown off its base by what Tate conservator Derek Pullen described as ‘an extraordinary gust of wind’ and was severely damaged in the process (fig.4). The bronze was badly scored and buckled and a large crack was torn in the structure (fig.5). It was then sent back to the Noack Foundry in Berlin so that the bronze could be repaired and re-patinated before an acrylic lacquer coating was reapplied to the surface. The sculpture was then returned to its position in the centre of an ornamental pond where it stood until 2004, when the surrounding area was re-landscaped. At this point the decision was made to place the sculpture on a new concrete plinth and to paint the bronze base black. Tate also improved the sculpture’s fixings to make it more secure.

Lyndsey Morgan

December 2010

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', December 2010, in Alice Correia, ‘Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, August 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

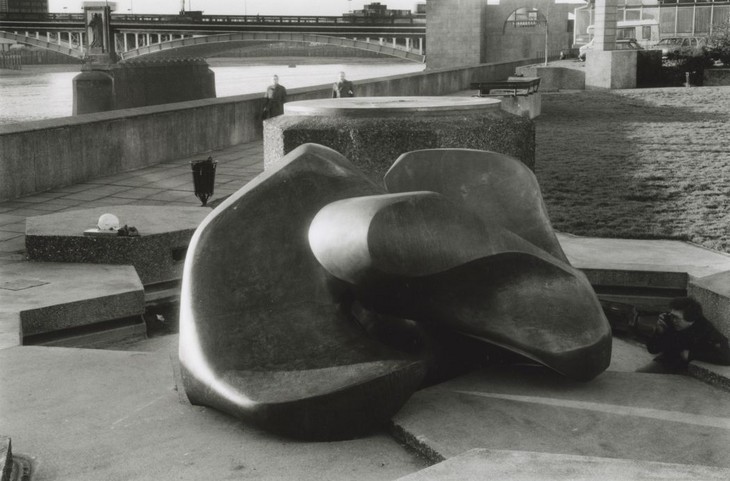

Locking Piece is made up of two large interconnecting forms stacked one on top of the other. It is one of Henry Moore’s best known public sculptures and has been on display near Tate Britain in Riverside Walk Gardens, Millbank, since 1968, having been gifted to Tate by the artist a year earlier. Tate’s work was the third of three bronze casts of this sculpture produced between 1964 and 1967, and was originally the artist’s copy.

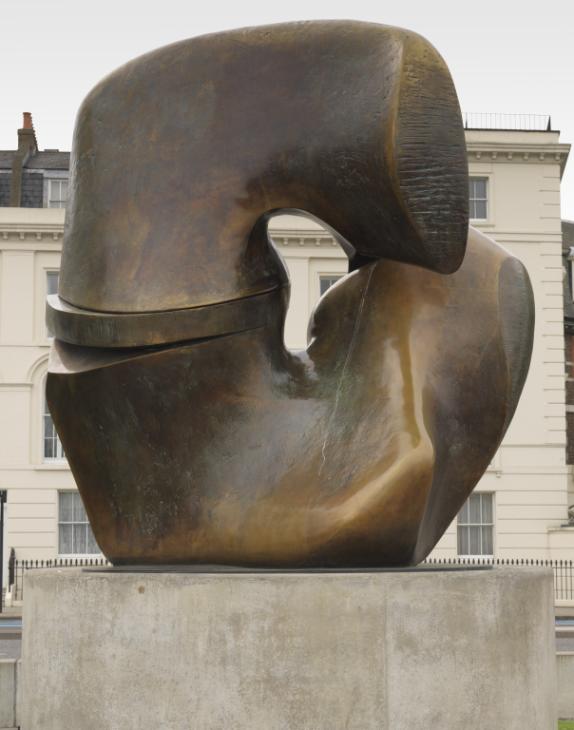

The two large pieces that comprise the bulk of Locking Piece are formed of amorphous protrusions that connect individual parts of the sculpture together or project into space at various angles, although the overall shape is quite compact. A hollow space at the centre of the sculpture is created where the upper piece arches over the concave piece below (fig.1). At one end a third, flatter, disk-like piece is wedged between the facing edges of the two larger pieces like cartilage between two bones. Here, both the upper and lower projections are short, tubular and have straight edges on one side. The lower form also has an irregular surface that slopes at a diagonal, causing the disk-like piece to rest unevenly upon it. The form projecting from the upper piece arches up and over the hollow space into a second, thinner protrusion with a curved face and tall, broad sides. This form projects almost horizontally to overhang the lower piece (fig.2).

Henry Moore

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

At the other end of the sculpture a thin spur from the upper piece appears to hook into a crevice in the lower piece. This cavity is formed by a rounded, twisting mass crossing the outer edge of the sculpture at a diagonal angle and a thin, faceted wedge that rises up from the base (fig.3). From one side, in between the bulkier forms joined by the disk at one end and the interlocking spurs at the other, is a tall, narrow, vertical gorge created by the curvature of the upper and lower pieces.

In 1966 Moore’s biographer Donald Hall described Locking Piece as follows:

The Locking Piece, in its final shape, is a generally circular bronze, nine feet high, in two parts which fit together like a child’s puzzle. It doesn’t resemble one thing ... There’s a portion of it which looks like an elephant’s foot; there are scraps of landscape and of natural objects; there are bits and pieces of many faces, including a fragment of T.S. Eliot’s nose. The more abstract a sculpture is, the more inclusive it can be of form experience. Walking around Locking Piece, the observer encounters a series of soft explosions of recollection; forms become other forms, a hill from one angle is a torso from another, with a sort of wit in the sudden shift in scale. The Locking Piece is the end result of thousands of things seen and things touched.1

Origins and facture

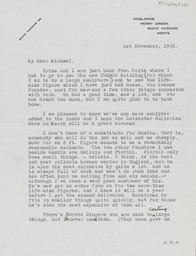

In 1964 Moore traced the origins of the two interlocking forms that comprise Locking Piece to a specific moment, stating:

The maquette for this two-piece Locking Piece came about from two pebbles which I was playing with and which seemed to fit each other and lock together, and this gave me the idea of making a two-piece sculpture – not that the forms weren’t separate, but that they knitted together. I did several plaster maquettes, and eventually one nearest to what the shape of this big one is now pleased me the most and then I began making the big one.2

Moore reiterated the sculpture’s indebtedness to two interlocking pebbles in 1980 by telling a similar anecdote.3 However, in 1968 he provided a slightly different account of the sculpture’s origins, stating that ‘the germ of the idea originated from a sawn fragment of bone with a socket and joint which was found in the garden. Given this theme, I made the complete sculpture’.4 Despite their differences, it is possible that both of these explanations are true, and that Moore found an equivalent to the interlocking pebbles in bone joints, working from both sets of objects to develop his sculptural ideas.

A mounted bone fragment in Moore’s studio may have provided the source for Locking Piece (fig.4). The bone, believed to be a vertebra, features a thin spur curving into two rounded forms on either side. The footprint of Locking Piece takes a similar shape (fig.5), which suggests that Moore may have begun making his maquette for the sculpture by creating a plaster reproduction of the bone, which he then modified.

Bone mounted on a wooden base in Moore's studio

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia, July 2013

Fig.4

Bone mounted on a wooden base in Moore's studio

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia, July 2013

Footprint of Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Footprint of Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore looked increasingly to bones and skeletal structures during the 1960s, not only for their formal qualities but for their symbolic properties as well. The critic Albert Elsen recalled that, during a visit to the artist’s studio in 1967, ‘Moore clenched his fist making his knuckles white and pointed out how he wanted to show the force of the bone’s pressure on the skin’.5 Moore’s interest in exposing the structural tension and strength of bones may serve to explain the arrangement of forms in Locking Piece. As Moore told Elsen, ‘the real skeleton becomes the outer shell of the body in my work. If a work was all flesh and no bone, it would have no architectural structure’.6

Henry Moore

Working Model for Locking Piece 1962

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Working Model for Locking Piece 1962

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

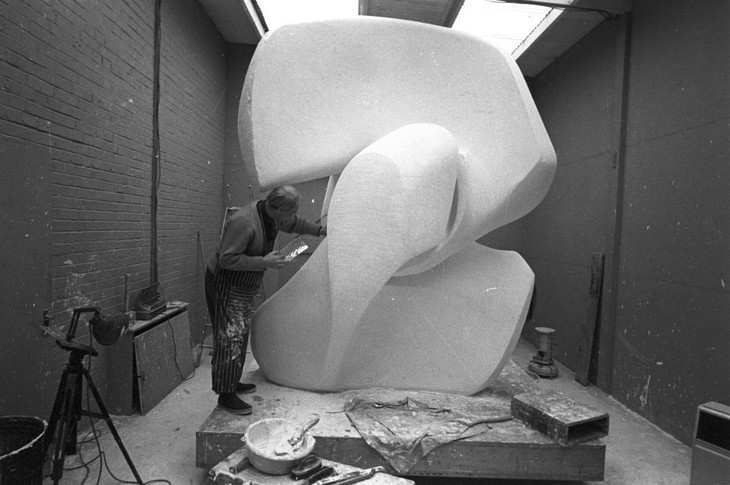

In order to make the full-size Locking Piece Moore’s assistants would have used the working model as a guide. According to Hall, Moore began work on the full-size plaster in October 1963 and completed it by February 1964 (fig.7). Hall recorded that:

to make the large version, Moore’s assistants started all over again, with measuring marks on the three-foot piece and a huge armature. This time the plaster would be too large to cast in one piece; it would have to be sawed into several pieces for casting, and so the armature could have no nails or wire. They tied sticks together with ropes, and draped cheesecloth from the extremities instead of wire.12

Having constructed the armature, the hollow structure was then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric onto which layers of plaster could be built up. Moore’s assistants generally worked autonomously, but when it came to Locking Piece Witkin observed that, ‘I’ve never seen Henry so involved as with this one’.13

Full-size plaster version of Locking Piece at Hoglands c.1963–4

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Full-size plaster version of Locking Piece at Hoglands c.1963–4

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Hall recounted that by late December 1963, although it looked finished, the plaster still required significant work. While working on it in the studio Moore could only stand a few feet away from the sculpture and was therefore unable to obtain a full view of its forms as they would be seen in the round (fig.8). Bad weather had prevented him from taking the plaster outside, where he could view it from a distance. Hall visited Moore on 20 December and recorded that Witkin and Robertson-Swann pushed the plaster out of the studio and onto the concrete patio on a wooden base with casters before slowly rotating it for Moore’s benefit. The working model was placed alongside the larger plaster so that Moore could compare the two at each rotation. Moore did not replicate the working model exactly but chose to make various adjustments to account for the increased height of the full-size sculpture. Hall described how, ‘after Moore had stared hard at the two Locking Pieces from each new angle, he started giving directions for revision, sometimes making rapid pencil sketches in a notebook while Isaac Witkin looked over his shoulder’.14

Full-size plaster version of Locking Piece in the studio at Hoglands c.1963–4

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Fig.8

Full-size plaster version of Locking Piece in the studio at Hoglands c.1963–4

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

After the plaster had been built up to the required size Moore worked into the surface using an array of tools including spatulas, cheese graters and chisels. These tools could be used to produce a variety of textures depending on the consistency of the plaster as it dried, and the different types of markings, grooves and cuts Moore made were reproduced in the cast bronze. The outer surfaces of Locking Piece are generally smooth and highly polished, while the inner areas have been heavily textured with short, shallow incisions. Deeper and longer horizontal gouges have been made in the thin face of the overhanging projection (fig.9).

According to Hall, the full-size plaster version of Locking Piece was completed on 26 January 1964. Tate’s bronze cast of this sculpture was made at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin using the sand casting technique.15 This would have required the foundry technicians to carve up the plaster sculpture into sections and take moulds from each individual piece. These moulds would then be filled with molten bronze, which hardened into cast pieces of the sculpture. Once all the individual pieces had been cast in this way they were welded together and their casting seams were filed down until the joins between them were barely perceptible. However, some casting seams on Locking Piece have partially re-emerged over time (fig.10). This usually occurs when the metal used to weld the sections together has a different composition to the bronze. A number of small, square patches on the surface indicate where the bronze has been replaced or repaired (fig.11). These patches may have been inserted where the surface had a fault or was damaged at a later date.

Detail of welding seam on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of welding seam on Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of repair to Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Detail of repair to Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After it had been cast and assembled the bronze sculpture was patinated. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and can develop naturally when the sculpture is displayed outdoors; bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, and exposure to chemicals in the air causes the copper to oxidise and turn the surface green over time. However a patina is usually achieved and controlled artificially by applying chemical solutions to the preheated bronze surface. Moore usually patinated bronze sculptures at his studio. However, during the 1960s and early 1970s he regularly travelled to the Noack Foundry and patinated his larger sculptures there to avoid the cost of transporting them. It is uncertain where Locking Piece was originally patinated but it has since been re-patinated several times. It has a variegated brown patina punctuated with reddish-amber and dark green shades. These colours are maintained by a wax coating which has been reapplied on multiple occasions (fig.12).

Reception and interpretation

Although Locking Piece appears to be an abstract sculpture, in 1977 the curator Alan Bowness suggested that it offered ‘a paradigm of the human relationship, with figures groping, touching, embracing, coupling, even merging with each other ... in the Locking Piece the forms are gripped in a tight embrace’.16 Moore had long believed that non-representational works of art could reveal deeper truths about humanity, stating in 1934 that:

Because a work of does not aim at reproducing natural appearances it is not, therefore, an escape from life – but may be a penetration into reality, not a sedative or drug, not just the exercise of good taste, the provision of pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination, not a decoration to life, but an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to greater effort of living.17

In an article for the journal Art International published in 1967, the critic Albert Elsen proposed that Locking Piece, along with other works such as Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964 (Tate T02299) and Two Piece Sculpture No.7: Pipe 1966 (Tate T02300), revealed a newfound freedom in Moore’s approach to abstraction. For Elsen, by the late 1960s Moore’s reputation was such that he allowed himself to move beyond ‘his signature themes of the reclining figure or the mother and child’ to undertake a more considered and sustained engagement with abstract forms that surpassed his earlier experiments of the 1930s. Elsen suggested, ‘late in his career Moore seems to have become more boldly and consistently inventive rather than interpretive, without withholding his natural generosity of spirit or the fullness of intellect and feeling with which his figural work has always been endowed’.18

While most critics, including Bowness, Herbert Read and Robert Melville, agreed that Locking Piece was best understood with reference to Moore’s interest in bones and the structures of skeletons, others have acknowledged the open-ended nature of Moore’s sculpture.19 For example, the artist and writer William Packer has argued that Locking Piece ‘has the massive monumentality of a mill, fraught with that sense of the imminent, heavy horizontal turn. It has the domed form of a skull, that seems to clip and hinge together, jaw and cranium. Here are the smoothed and hollowed declivities and opportune points of pressure of the Venetian rowlock, here the deep cavity to hold the ball of hip or shoulder’.20 The multiple ways of perceiving Locking Piece reflected Moore’s belief that good sculpture invited divergent interpretations:

It must make you stop and look at it of its own accord irrespective of where it is. If it has an immediate explanation as to why it is there, the average person will see this, go away and lose interest. It is better if the sculpture should be of some challenge or of a mystery. I want sculpture that has a lot of interpretations, like Hamlet. It is important that there be continued interpretations ... People have an intrinsic interest in shapes. If a thing has a ‘universal touch’ it will interest generations.21

In 1968 Moore declared that ‘“Locking Piece” is certainly the largest and perhaps the most successful of my “fitting-together” sculptures’.22 Nine years later he elaborated why he considered it a success:

You see different shapes as you go around the sculpture. This is the result of trying to make a sculpture have a lot of variety even though I had the same unity throughout.

Unity in a work is easily achieved if all the forms are repetitious and the same. Also, it is easy to create variety if all the forms are consciously different. What is difficult is unity with variety.23

Unity in a work is easily achieved if all the forms are repetitious and the same. Also, it is easy to create variety if all the forms are consciously different. What is difficult is unity with variety.23

Following Moore’s account of the work, the ‘universal touch’ of Locking Piece might perhaps be identified in the balance between ‘unity’ and ‘variety’ to which Moore claimed to aspire, and specifically in his use of natural forms to attain it. Although the critic John Russell argued that the sculpture was ‘grim-faced’, Bowness concluded that works such as Locking Piece made between 1964 and 1973 ‘represent, in my opinion, not only the culmination of Moore’s achievement but the most original and challenging sculpture being produced anywhere in the world today’.24

Display and acquisition

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast 1964 on display outside the British Pavilion at the Montreal Expo in 1967

Tate T02293

Photo: Anthony Blee

Fig.13

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast 1964 on display outside the British Pavilion at the Montreal Expo in 1967

Tate T02293

Photo: Anthony Blee

Crosby’s dismissal of Locking Piece as a ‘standard Henry Moore’ reflects an attitude towards Moore’s work that became increasingly pervasive during the late 1960s and 1970s. According to the art historian Iain Boal, by this time Moore had established himself as ‘the open-air sculptor par excellence’ through his commissions for urban spaces and corporate headquarters.26 In the context of the British Pavilion and its overt focus on youth, innovation and fashion, these associations and the monumental nature of the sculpture itself may have made Locking Piece appear outmoded.

Upon its return from Montreal Locking Piece was displayed outdoors in Riverside Walk Gardens, Millbank, close to the Tate Gallery. In January 1966 Tate Director Norman Reid had received a letter from A.G. Dawtry, town clerk for the City of Westminster, informing him of the city council’s intention to build a walkway along Millbank terminating in a small public garden next to Vauxhall Bridge. The inclusion of a piece of modern sculpture had been a feature of the initial plans for the garden and by the end of 1966 the architects commissioned to design the garden had contacted Moore to enquire about the availability of Locking Piece. Moore confirmed that the sculpture was due to return from the Montreal Expo at the end of 1967 and would thus be available for the completion of the garden in 1968. Moore then gifted Locking Piece to the Tate, who in turn agreed to loan the sculpture to Westminster City Council.

The sculpture was displayed on a hexagonal pedestal finished in a dark aggregate, surrounded by a pool crossed by arcing jets of water (fig.14). It was unveiled on 19 July 1968 as part of Moore’s seventieth birthday celebrations. Following a visit to Hoglands in December that year, Norman Reid noted that the artist ‘expressed his particular satisfaction at the siting of the Locking Piece’.27 When Locking Piece entered the Tate collection in 1967 Moore regarded the sculpture as part of a larger gift that he intended to make to the gallery. The sculpture was thereby formally presented by the artist to the Tate in 1978 and was included in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, which was held that same year.

Locking Piece Installed in Riverside Walk Gardens, Millbank

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Locking Piece Installed in Riverside Walk Gardens, Millbank

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Locking Piece has remained in the Riverside Walk Gardens since 1968, although in 1976 Moore expressed reservations about its original plinth. In photographer David Finn’s anthology of his outdoor sculpture, Moore said of Locking Piece, ‘The location isn’t bad, but I don’t like the idea of the fountain – nor that great big thing the sculpture is standing on, its pedestal is too powerful for the sculpture; it knocks the strength out of the sculpture’.28

In January 1990 the sculpture was blown off its base by what Tate conservator Derek Pullen described as ‘an extraordinary gust of wind’ during a fierce storm and was severely damaged (fig.15).29 Pullen reported that ‘the hollow bronze has suffered a severe impact resulting in structural and surface damage requiring foundry repairs and restoration’.30 The bronze was badly scarred and dented, with welding seams opening up and a large hole torn in the sculpture near its base. In order to repair the damage Locking Piece was sent back to the Noack Foundry in Berlin. Its surface was also re-patinated and given a protective acrylic lacquer coating.

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 blown off its base in 1990

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 blown off its base in 1990

Tate T02293

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In November 2002 Westminster City Council began to draw up plans for re-landscaping Millbank Garden and considered relocating Locking Piece. Moore’s concerns about the size of the pedestal and the surrounding pool were debated at length. It was eventually agreed by Tate and the council that a tall pedestal should be retained as its height would not only allow the sculpture to be seen from all directions, but would also discourage climbing and vandalism. Although the position of the sculpture within the garden was not significantly changed, the pool surrounding the pedestal and its water jets were removed. In addition, a new pedestal was constructed, which, unlike the original, was cylindrical and had a smooth finish. The re-landscaping of the garden and the re-installation of the sculpture were completed in the summer of 2004 (fig.16).

Locking Piece was cast in an edition of three plus one artist’s copy. The first bronze cast was exhibited at Documenta 3 in Kassel, Germany, in the summer of 1964 before it was relocated to its designated site at the Banque Lambert in October 1964.31 During that same summer a second full-size plaster version of Locking Piece was exhibited at the Tate Gallery as part of the Gulbenkian exhibition.32 At this time the Friends of the Tate considered acquiring the plaster for the gallery. It was priced at £1,400, which the gallery’s director Norman Reid observed was ‘the cost of the cast and transport’.33 Although the Friends were generally in favour of purchasing a sculpture by Moore, the majority elected to wait until a large outdoor bronze became available and purchased René Magritte’s painting L’Homme au Journal 1927 (Tate T00680) instead. The second bronze version of Locking Piece was also cast in the summer of 1964 and was acquired by the Gemeente Museum in The Hague, Netherlands. The third cast, now owned by Tate, was the artist’s copy, although the casting date is unrecorded. A fourth was produced at an unknown later date and is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation. It is likely that the original plaster used by Noack was destroyed after the bronzes had been cast, while the other full-size plaster was destroyed in 1971 and replaced with two fibreglass casts, both of which are now owned by the Henry Moore Foundation.

Alice Correia

August 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Warren Forma, Five British Sculptors (Work and Talk), New York 1964, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.144.

‘I was playing with two pebbles ... and somehow or other they got locked together and I couldn’t get them undone and I wondered how they got into position and it was like a clenched fist ... Anyhow, eventually I did get it to [separate]; by turning and lifting, one piece came off the other. This gave one the idea of making two forms which would do that and later I called it “Locking Piece” because they lock together’. Henry Moore cited in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.291.

Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, summer 1967, p.356.

Ibid., p.10. It is probable that other assistants helped in the construction of Locking Piece, but their names are unrecorded; other assistants working for Moore in 1962–4 included Geoffrey Greetham, Robert Holding, Derek Howarth, Roland Piché, Clive Sheppard, Hylton Stockwell and Yardini Yeheskiel.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.226.

Sand casting is a technique whereby a model is buried in sand to create a mould from which the bronze can be cast. Sand casting is quicker and less labour intensive than lost wax casting but is generally less suitable for reproducing very intricate shapes or surface details.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, cited in Wilkinson 2002, pp.192–3.

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, p.42.

See Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.246, and Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970, p.261.

William Packer, ‘Locking Piece’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.267.

Theo Crosby, ‘Design and Purpose in World Exhibitions’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, vol.116, no.5139, February 1968, p.247.

Iain A. Boal, ‘Ground Zero: Henry Moore’s Atom Piece at the University of Chicago’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.224.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Locking Piece 1963–4, cast c.1964–7 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, August 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www