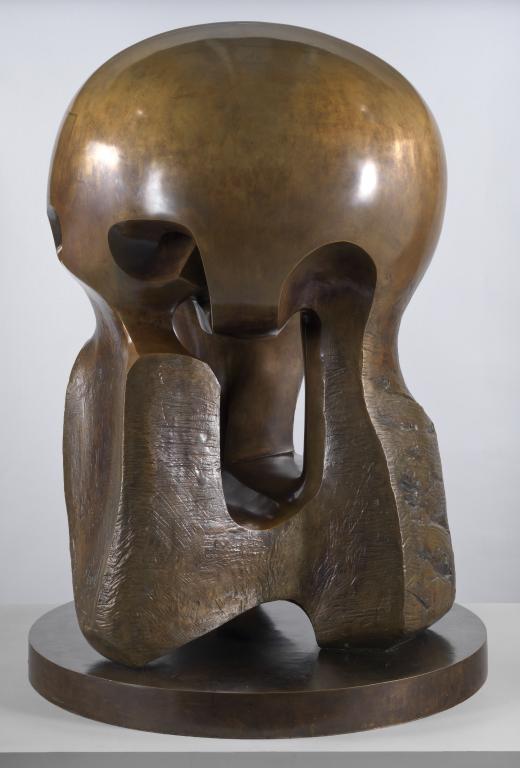

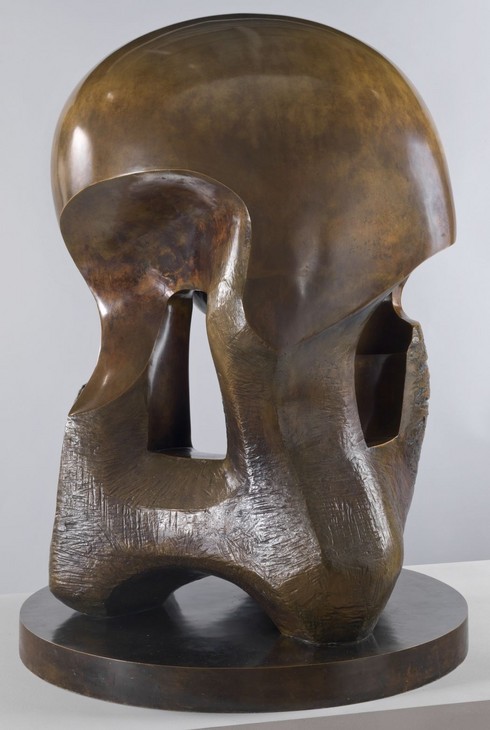

Henry Moore OM, CH Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965

Image 1 of 8

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964-5, cast 1965© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy)

1964-5, cast 1965

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

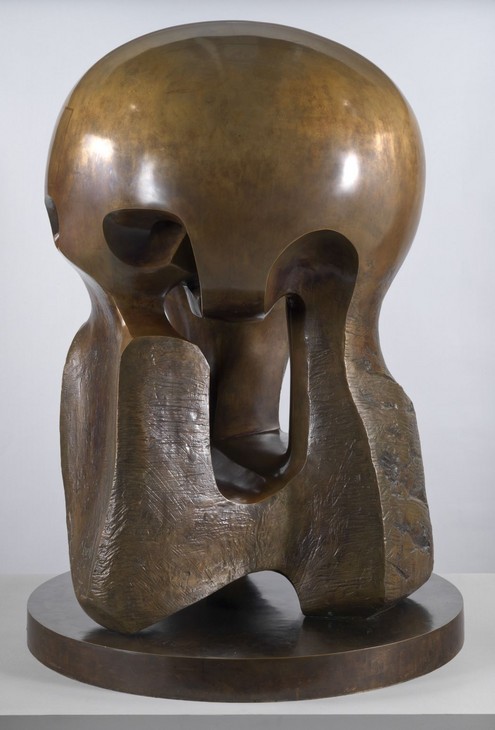

Atom Piece is the working model for Moore’s monumental outdoor sculpture Nuclear Energy 1964–6, commissioned by the University of Chicago to commemorate the first controlled nuclear chain reaction. With its domed top, reminiscent of a mushroom cloud, the work relates to Moore’s earlier series of ‘helmet head’ sculptures, and was described by Herbert Read in 1965 as symbolising ‘those forces which modern man has released for ends which cannot yet be imagined or realised’.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy)

1964–5, cast 1965

Bronze

1182 x 915 x 915 mm

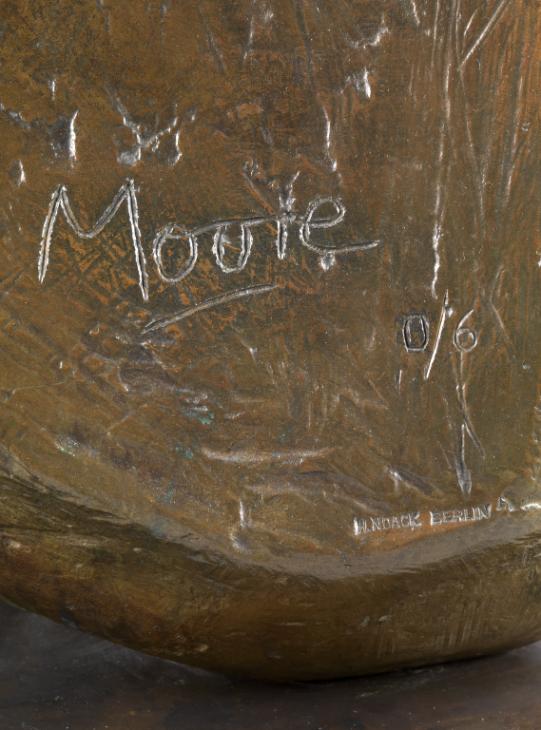

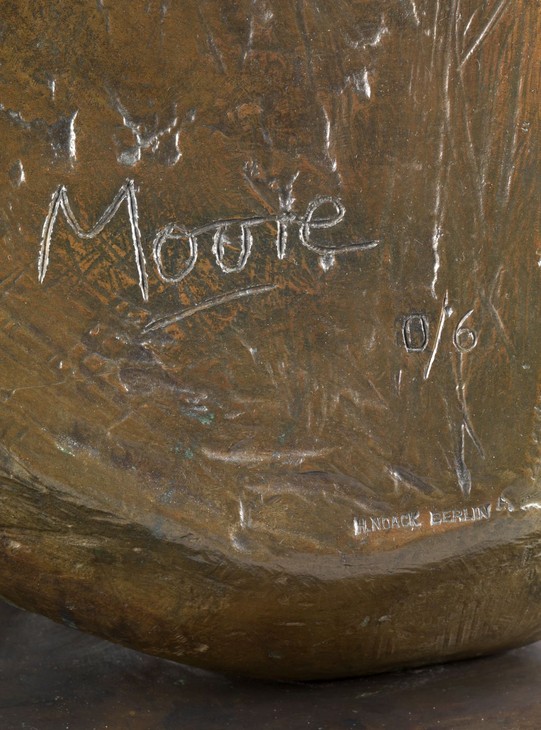

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on foot

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02296

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy)

1964–5, cast 1965

Bronze

1182 x 915 x 915 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on foot

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02296

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1965

British Sculpture in the Sixties: An Exhibition Organised by the Contemporary Art Society in Association with the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation, Tate Gallery, London, February–April 1965 (?another cast exhibited no.77).

1966

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Salla Dalles, Bucharest, February–March 1966; Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, April–May 1966; National Gallery, Prague, June 1966; Israel Museum, Jerusalem, September–October 1966; Tel-Aviv Museum, Tel-Aviv, November–December 1966, no.31.

1967

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October–November 1967; Confederation Art Gallery and Museum, Charlottetown, January–March 1968; Arts and Cultural Centre, St Johns, March–May 1968; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, June–September 1968.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.60.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.134.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, 12 August–5 October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.70.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.78.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.106.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.13.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal and Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.22.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.105.

1981–2

Henry Moore: Exposició Retrospectiva, Escultures, dibuixos i gravats 1921–1981, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, December 1981–January 1982, no.65.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.44.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.111.

1986

The Art of Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings and Graphics 1921–1984, British Council touring exhibition: Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo, April–June 1986; Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, June–July 1986.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.184.

1997–8

Henry Moore: Animals, Gerhard-Marcks Haus, Bremen, October 1997–January 1998; Georg-Kolbe-Museum, Berlin, February–May 1998; Städtischen Museen, Heilbron, May–August 1998.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.50.

2006

Henry Moore, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona, July–October 2006, no number.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.148.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.246–8 (?another cast reproduced pls.237–8).

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Gallery, Rome 1965 (?another cast reproduced).

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough New London Gallery, London 1965 (?another cast reproduced, front cover).

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, Summer 1967, pp.352–8.

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5 (?another cast reproduced p.43).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.194–5 (?another cast reproduced pl.197).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.345, 407–8.

1973

David H. Katzive, ‘Henry Moore’s Nuclear Energy: The Genesis of a Monument’, Art Journal, vol.32, no.3, Spring 1973, pp.284–8.

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977 (?another cast reproduced pls.16–18).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (Nuclear Energy 1964–6 reproduced pp.446–51).

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.188–90 (original plaster reproduced pl.168).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.53.

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.136–7, reproduced p.136.

2001

Chris Stephens, ‘Sculptural Energy’, Tate: The Art Magazine, no.24, Spring 2001.

2003

Iain A. Boal, ‘Ground Zero: Henry Moore’s Atom Piece at the University of Chicago’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.221–42.

2003

Chris Stephens, ‘Henry Moore’s Atom Piece: The 1930s Generation Comes of Age’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.243–56.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Nuclear Energy 1964–6 reproduced p.74).

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.201.

2012

Catherine Jolivette, ‘Science, Art and Landscape in the Nuclear Age’, Art History, vol.32, no.2, April 2012, pp.252–69 (Nuclear Energy 1964–6 reproduced p.263).

Technique and condition

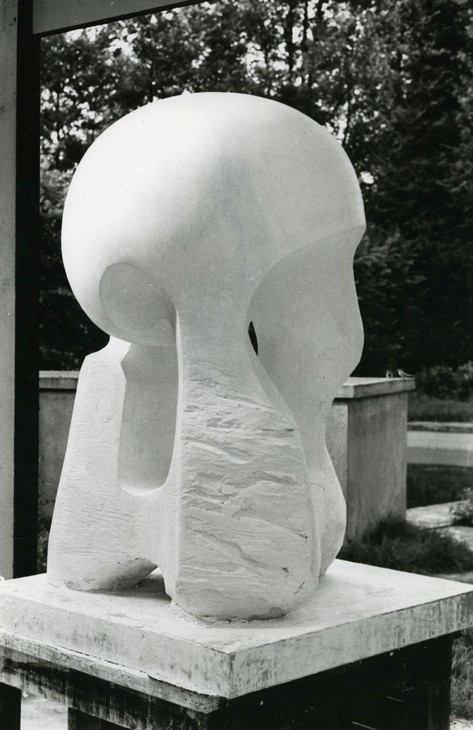

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) is a bronze sculpture comprising a complex pierced form capped by a large dome, and is mounted on a circular bronze base. Moore made the original model for this sculpture in plaster, which was used to make the mould from which the bronze was cast. The model was made by applying successive layers of plaster to a supportive armature, which was constructed from lengths of wood (fig.1). Once the plaster had set he would have carved it back to refine the form and add detail to the surface (fig.2). The dome was sanded to a smooth finish while the lower areas were striated using a range of tools. All the textures were retained in the finished bronze sculpture, which was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in an edition of six plus on artist’s copy.

Photograph of armature for Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in Moore's studio 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Photograph of armature for Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in Moore's studio 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

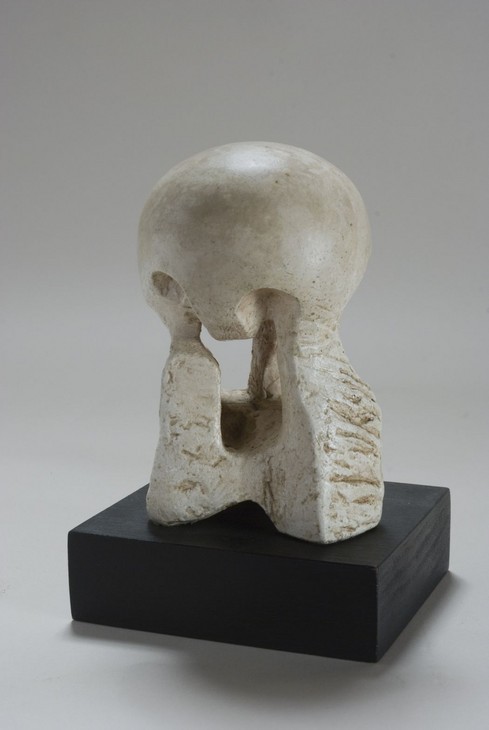

Plaster version of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) at Hoglands in 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Plaster version of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) at Hoglands in 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

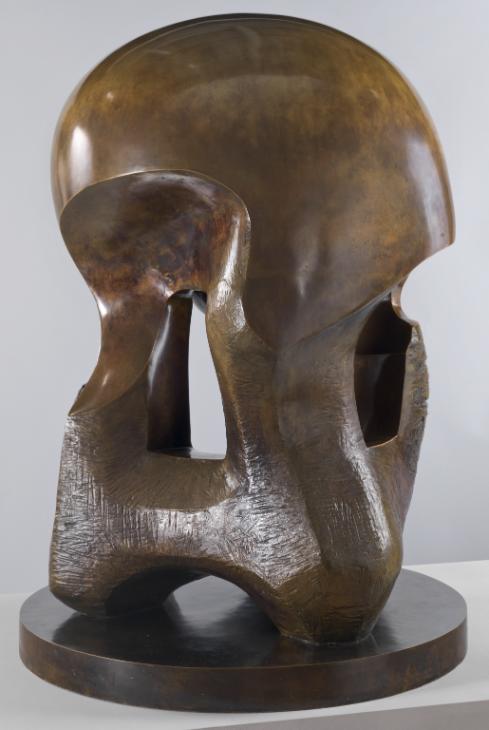

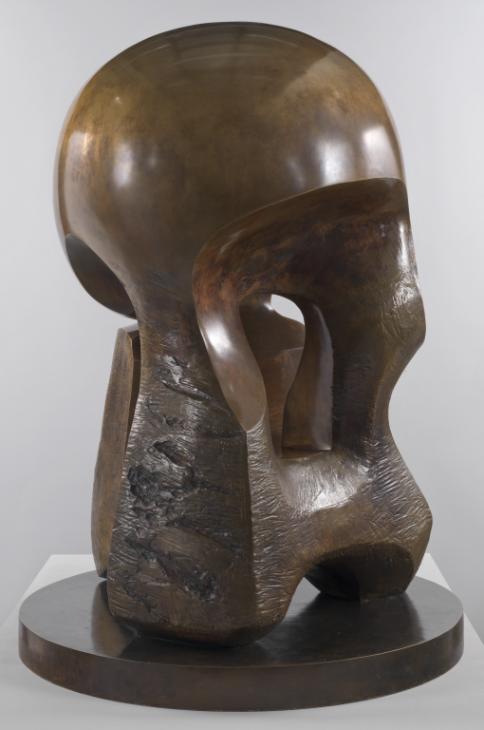

The maximum size of a cast piece of bronze is determined by the size of the crucible used at the foundry, for bronze must be cast in a single pour. To cast this sculpture the plaster original had to be cut into two pieces, which were cast separately and subsequently welded together. A horizontal weld line approximately halfway up the sculpture testifies to this process (fig.3). This seam was polished where it traverses the dome, whereas on the lower surfaces it was integrated with the texture of the surrounding bronze using punches and chisels.

Detail of welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of patina on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface of the bronze was artificially patinated, which, as well as colouring the sculpture, also served to disguise any flaws, welds or repairs in the cast. The process required chemical solutions to be applied to the surface of the bronze, triggering a reaction that produced coloured compounds. A thin, transparent brown patina was applied over the entire surface of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy), graded to deeper shades towards the lower, more heavily textured areas of the sculpture (fig.4). These brown shades are often achieved using solutions of potassium or ammonium polysulphide, applied at varying concentrations and temperatures to affect the depth of colour. Some of the interior and concave surfaces on the lower part of the sculpture have a warm, reddish colour that was likely produced by stippling ferric nitrate solution onto the bronze while it was heated with a blowtorch.

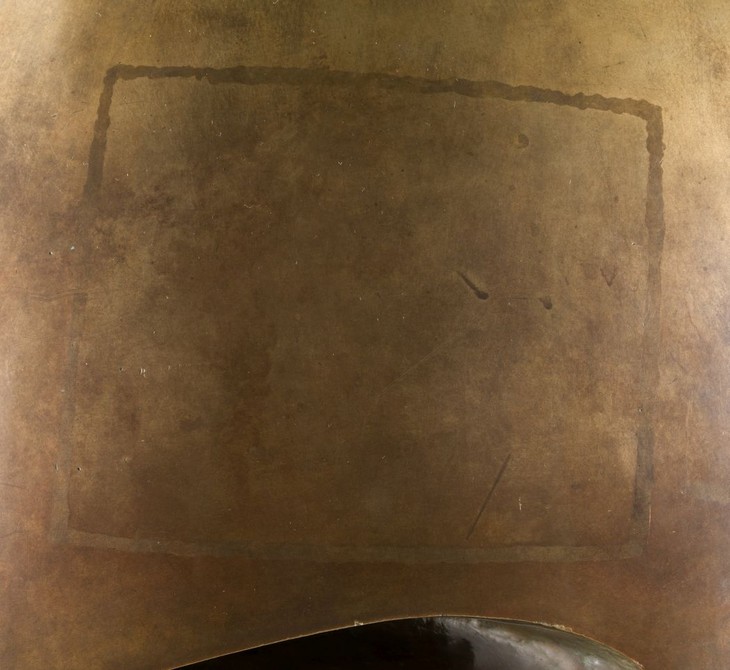

The base was filed and sanded after casting to give it a smooth surface and then patinated a dark brown colour bordering on black, perhaps using a combination of ammonium and potassium polysulphides. It was probably cast using the sand-casting technique and is reinforced by cast struts underneath. Rollers have been attached to the base, allowing the sculpture to be easily positioned on its plinth. The sculpture rests on the base at three points and is fixed at each point by three bolts inserted from underneath.

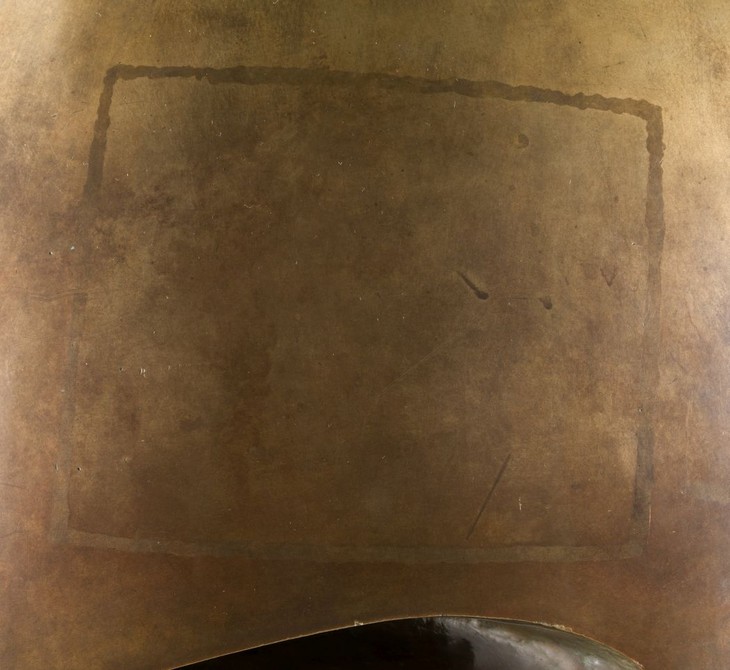

Detail of square welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of square welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

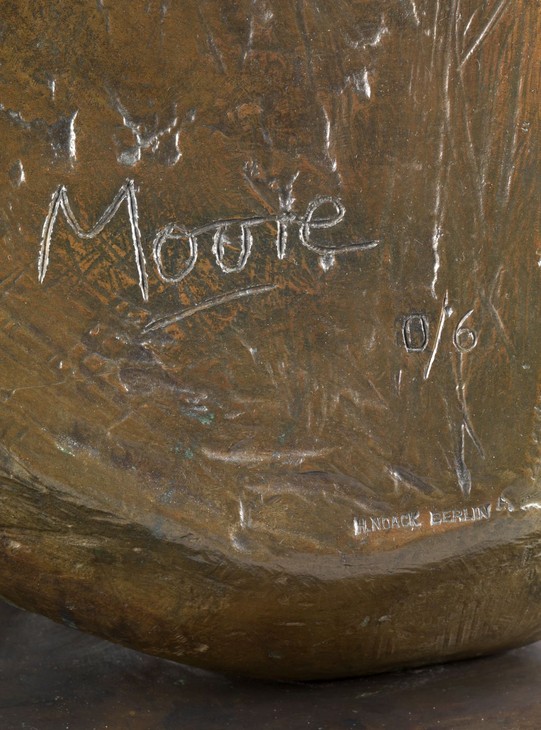

Detail of artist's signature, edition number and foundry stamp on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of artist's signature, edition number and foundry stamp on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A square outline can be seen on one side of the domed surface (fig.5). This appears to be a seam line created by welding a patch of metal to the cast, probably to repair a fault. The composition of the alloy used to make the seam was slightly different to the rest of the bronze and, as a result, the line has become more prominent over time having reacted with the patina and the atmosphere differently. There are green run lines on the inner surfaces of the sculpture that were probably caused by rain water during sustained periods of outdoor display.

The inscription ‘Moore’ is visible on the outside of one of the sculpture’s ‘feet’, near where it meets the base. The edition number 0/6 is underneath, and then below this the much smaller foundry stamp ‘H NOACK BERLIN’ (fig.6).

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

As its subtitle suggests, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5 represents the intermediary stage in the development of a much larger sculpture, Nuclear Energy 1964–6, which Moore was commissioned to make for the University of Chicago to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first controlled generation of nuclear power, conducted by the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi in 1942.

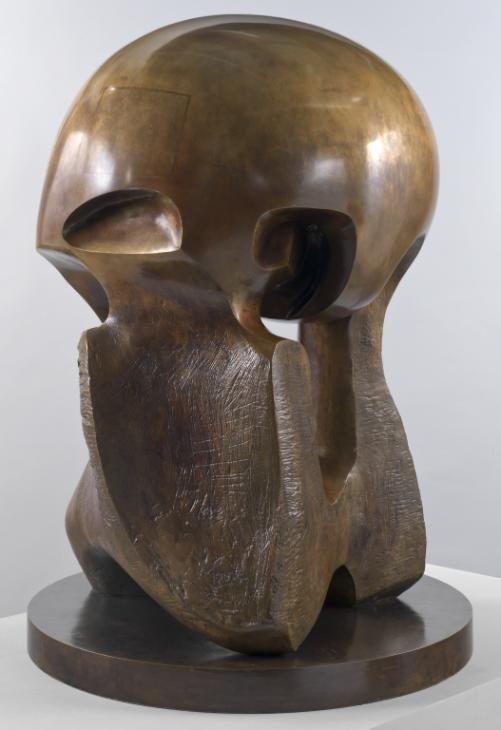

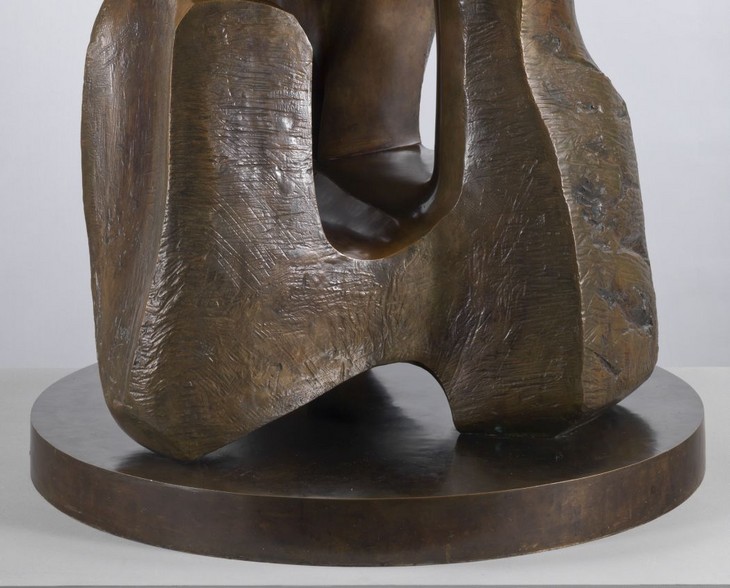

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) stands at just over one metre tall on a shallow circular base. It forms a single unit but comprises two distinct sections. The lower part is made up of three roughly textured vertical forms connected near the base by a horizontal shelf of bronze. These three column-like blocks merge and swell into the upper section, which takes the form of a highly polished dome (fig.1).

The lower section resembles a tripod, with three feet arching upwards into a thick, slightly concave platform, which hovers above the base. The irregular arches formed between the three feet are suggestive of caves or coastal arches and expose the underside of the sculpture (fig.2). The outer surfaces of these forms are heavily textured with horizontal striations, forming a visual parallel to cliff stacks that may owe a debt to the legs of Moore’s earlier Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960 (Tate T00395). Each of the three upright forms are shaped and textured differently. The largest is thin and wide with a concave outer face, another is smoother and has a flat lower edge, and the third is faceted and curves sharply inward. Two of them feature trenchant right-angled planes, suggesting that they have been cut into and hollowed out to produce the internal cavity at the centre of the sculpture. Visible between the upright forms are the underside of the dome, which curves slightly to echo its outer surface, and the smooth horizontal plane below it, which has been incised with a single concave groove. The texture of the underside of the dome indicates that a spatula was used to apply the plaster to the model from which the bronze was cast. A horizontal seam encircles each leg where it meets the dome, identifying where the upper and lower sections were welded together after casting (fig.3). A circular plug, visible halfway along the seam on the outer face of the widest leg, and a bronze patch marked by a square welding seam on the surface of the dome, were probably inserted to correct faults in the bronze.

Detail of lower section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of lower section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

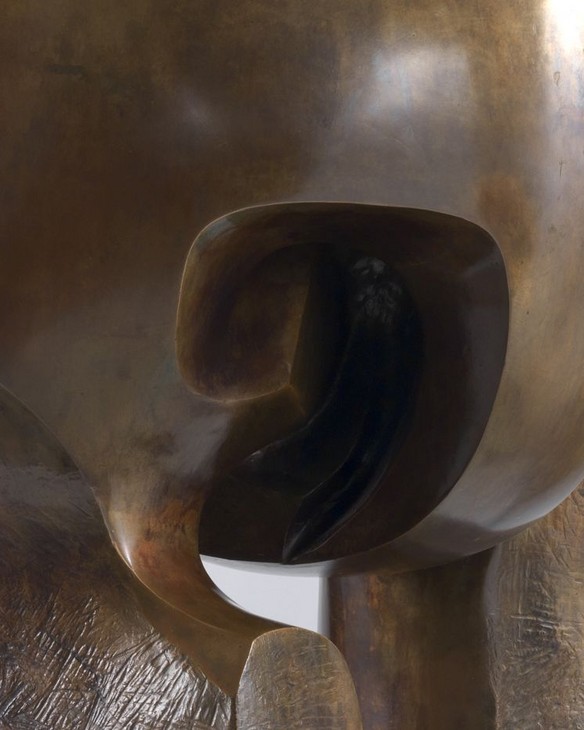

The domed upper part of the sculpture has a highly polished outer surface (fig.4). Elliptical depressions and curves have been cut into the lower edge of the dome, a thin section of which curls inward to form its underside. From certain angles the position and shape of these indentations may be seen to resemble eyes, while a recessed spiral hollow adjacent to the widest leg also recalls the shape of an ear (fig.5).

Detail of upper section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of upper section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of recessed area in upper section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of recessed area in upper section of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The Chicago commission

By the early 1960s demand for public sculptures to furnish newly built city squares and courtyards had increased dramatically. Moore’s commission for the Unesco building in Paris in 1957–8 (see Working Model for Unesco Reclining Figure 1957, Tate T00390) had alerted international clients to the artist’s large-scale work, and earned him numerous commissions. On 14 November 1963 William McNeill, Professor of History at the University of Chicago, wrote to Moore to enquire whether he would be interested in creating a large-scale outdoor sculpture commemorating the work of Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. On 2 December 1942 Fermi had achieved the world’s first controlled nuclear chain reaction in the university’s laboratories, and the university was seeking to erect an appropriate monument to this achievement. The social historian Iain Boal has noted that ‘the reasons why Moore made the Chicago shortlist are obvious enough: by the early 1960s the open-air sculptor par excellence was decorating the plazas and cathedrals of capitals with his bronzes. He had become the safe modernist master’.1

Moore replied to McNeill on 2 December 1963 expressing an interest in the commission, stating:

I realize what a tremendous happening that was, and that a monument for such a triumphant breakthrough may be called for. It seems an enormous event in man’s history, and a worthy memorial for it would be a great responsibility and not easy to do. However, it would be a great challenge and something I might like to consider.2

Later that month McNeill, Professor of Art Harold Haydon, and the architect Ike Colburn arrived at Moore’s home, Hoglands, in Hertfordshire to discuss the commission further. Moore had little time to prepare for the visit, but presented the delegation with a small maquette to consider. Moore rarely designed sculptures to a specific brief; instead he would invite commissioning parties to choose from a selection of maquettes or mid-sized working models already in development, which allowed him to retain artistic control over a commission and develop ideas for his work independently of others. Moore later recalled that:

It’s a rather strange thing really but I’d already done the idea for this sculpture before Professor McNeill and his colleagues from the University of Chicago came to see me on Sunday morning to tell me about the whole proposition ... As they told me the story and the situation, I gradually remembered that only a fortnight previously, I’d been working in my little maquette studio (because I was trying to think as they told me what form or what shape such an idea brought to my mind) and the story reminded me of a sculpture I’d already done, about six inches high which was just a maquette for an idea. I said to them that I thought I had done the idea as far as I would be able to and I showed them the maquette, and I said, ‘I’m going to make this sculpture into a working model’ ... ‘Would you wait until I’ve made this working model which will be about four or five feet in height and then when you see it, we could come to a decision whether it would really be suitable for your purpose?’3

McNeill also recalled his visit to Perry Green:

He did indeed produce a maquette on the spot, a piece of plaster about six inches high if I remember aright [sic]. He said he made it a day or two before our visit in anticipation of our arrival, after fondling bits of odd shaped stones that he used to stimulate the imagination. He showed us the box in which these eroded stones – pebbles from some beach I believe – were kept ... I cannot tell what [the] others thought of the maquette; I felt pleased that he was willing to go ahead on the open-ended basis, with no binding obligation on either side. When the full-scale piece emerged, well then we could have a look and decide: and try to find the money needed. I had little doubt that Henry Moore would produce a piece we could be proud of: I could not really visualize the effect of a bronze sculpture 12 or 14 feet high in the shape of the piece of white plaster one holds in the hand.4

Boal has observed that Moore’s and McNeill’s respective accounts of when the small maquette was made are contradictory. If the maquette was made a day or two before the visit, as McNeill recalled, it would suggest that the sculpture was designed in response to the commission. If, however, it was made a fortnight before the visit, as Moore suggested, it is possible that he made the maquette without any knowledge of the Chicago commission.5 In any case, as Moore noted the maquette for Atom Piece was made in his small studio in the grounds of Hoglands. When asked in 1960 how he arrived at an idea for a sculpture, Moore replied:

Well, in various ways. One doesn’t know really how ideas will come. But I can induce them by starting with looking at a box of pebbles. I have collected bits of pebbles, bits of bone, found objects, and so on, all of which help to give an atmosphere to start working. Then with those pebbles ... I sit down and something begins. Then perhaps at a certain stage the idea crystallizes and then you know what to do, what to alter.6

This account correlates with McNeill’s description of Moore ‘fondling bits of odd shaped stones’, and would suggest that the origins of Atom Piece may be partially traced to Moore’s pre-existing interest in weathered rock formations. However, shortly before the inauguration of the full-size sculpture in 1967 Moore wrote to McNeill responding to an earlier request:

You ask if I would bring a few pebbles used when working on the preliminary conception of the statue. Actually the idea for NUCLEAR ENERGY did not come from any particular natural object. I can’t fully explain how the idea of it arrived, except that it has some connection with earlier HELMET HEAD and the INTERIOR/EXTERIOR form sculptures of mine.7

From plaster to bronze

Henry Moore

Maquette for Atom Piece

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Maquette for Atom Piece

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Following the visit of McNeill, Haydon and Colburn, Moore began working on an enlarged ‘working model’ of the sculpture for the consideration of the Chicago committee. By systematically charting and measuring specific points on the surface of the plaster maquette it was possible to enlarge the design while retaining its original proportions. The enlargement process was carried out in the White Studio in the grounds of Hoglands, or, weather permitting, outside on the studio terrace. Some of the preliminary enlargement work is known to have been undertaken by Moore’s sculpture assistant Derek Howarth, probably with the help of Moore’s other assistants, who in 1964 were Geoffrey Greetham, Robert Holding, Roland Piché, Ron Robertson-Swann, Hylton Stockwell and Yeheskiel Yardini.11 Moore’s assistants would have first constructed an armature to the required size and approximate shape of the sculpture using numerous lengths of wood held together with daubs of plaster (fig.7). This was then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric, before layers of plaster were built up on top until only the tips of the armature rods could be seen (fig.8).

Photograph of armature for Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in Moore's studio 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Photograph of armature for Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in Moore's studio 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph of construction of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Photograph of construction of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) in 1964

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.12 Using an array of tools, including trowels, axes and cheese-graters, different types of markings, grooves and cuts could be made according to the wetness of the plaster as it dried, all of which were reproduced in the bronze cast. In 1977 the curator Alan Bowness drew attention to the contrasting textures in Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy), noting that ‘most of the post-war bronzes had rough, variegated textures, but from 1963 or so Moore began to introduce smooth and polished bronze surfaces. They sometimes contrast with the rougher areas, as in the polished cranium of the Atom Piece’.13

On 17 August 1964 Moore wrote to McNeill to update him on the progress of the working model: ‘I just wanted to tell you that I have finished the working-size version of what I have started calling ‘CHICAGO STATUE’, that is, I have made a sculpture from the small maquette you saw, about four feet high, so that I could work out refinements and small changes which were unsatisfactory in the small maquette’.14 Of particular significance here is Moore’s assertion that he made alterations to the original design as he was scaling it up.

Detail of artist's signature, edition number and foundry stamp on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of artist's signature, edition number and foundry stamp on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Two months later Moore wrote to McNeill stating, ‘I have decided to start work on the final size sculpture in plaster – to be cast in bronze. The working model is now complete and is being cast into bronze so we can get some idea of how bronze will suit it’.15 Moore employed the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to cast the working model, remarking in 1967 that ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.16 Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy in 1965. The edition number ‘0/6’ is inscribed on one of the feet of the sculpture underneath the artist’s signature, indicating that Tate’s cast of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) was originally the artist’s copy (fig.10).

Detail of square welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of square welding seam on Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Titling Nuclear Energy and exhibiting Atom Piece

The first bronze cast of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) arrived at Moore’s studio on 29 January 1965. It is unclear whether Tate’s example of the sculpture is this first cast or one of the six examples cast by Noack later that year. In February 1965 Moore sent a set of photographs of the completed bronze sculpture to the University of Chicago’s Memorial Planning Committee, and on 23 July McNeill wrote that ‘I am happy to be able to report that the University authorities have now approved the acquisition of your statue “Atom Piece”’.19 Although McNeill referred to the full-size sculpture as Atom Piece in his July letter, on 24 September he noted that ‘we must now learn to call [the sculpture] Nuclear Energy’.20 Moore had recently visited Chicago to view the site for the sculpture and on 25 September a press release announcing the commission stated: ‘The title of the work by Mr. Moore is Nuclear Energy. Mr. Moore agreed to this title after a lunch with the University of Chicago faculty members [on] Friday’.21 McNeill later recalled that the pun formed by ‘atom piece’ and ‘atom peace’ was ‘too close to be comfortable’ for many of the University’s senior members.22 However, as Boal has noted, ‘despite agreeing during his Chicago site visit in September 1965 to re-title the work, Moore continued himself to give the name Atom Piece, not only to the maquette and to the four-foot working model, but to the final unique cast bronze sculpture’.23

A cast of the working model was shown in the exhibition British Sculpture in the Sixties at the Tate Gallery, London, between February and April 1965, and further casts were exhibited at Moore’s commercial gallery, Marlborough Fine Art, at its Rome and London premises in May and July respectively. Exhibited under the title Atom Piece, the working model initially received mixed reviews. At the Marlborough New London Gallery it was displayed as part of a two-person exhibition of works by Moore and the painter Francis Bacon. In a review for the Times titled ‘Bacon and Moore again in Powerful Relation’, an unnamed critic singled out the sculpture:

It seems to have a complex significance. It would be possible to appreciate it from a purely abstract standpoint by reference to its hollows and convexities, the calculated difference between a polished smoothness and a rough texture of surface. Yet if one looks on it as incited by the thought of atomic explosion, its swelling dome as an equivalent of [a] mushroom cloud, one may feel it as a sign of the artist’s optimism that an image of stabilized power appears rather than of sinister disintegration.24

Overall the critic for the Times gave a positive review of both the formal qualities of the sculpture and its capacity for hope in an atomic age. Meanwhile, G.S. Whittet, writing in the art magazine Studio International, described the sculpture as:

a totemic head; it is a stylised naturalistic rendering of a damaged human – it is all of them and it is none of them for its exaggeration takes it out of the field of comparison with reality and instead remains as a paraphrase, a metaphor of the mortal condition.25

Whittet concluded his review of the exhibition by stating that, ‘It is no exaggeration to say that in twentieth-century art Henry Moore is the one who expresses, if not goodness, at least the strength and dignity that survive in this civilization’.26 However, the critic Edwin Mullins took an opposing stance in his review for the Sunday Telegraph, describing Atom Piece as ‘a brutish thing, based on a confused and pretentious idea’,27 while in the Guardian the critic Norbert Lynton called the sculpture ‘a prosaic image inflated beyond its formal capacity and then burdened with a title that stresses its vague similarity to a mushroom cloud’.28

Sources and symbolism

In his monograph on Moore, published in December 1965, the critic Herbert Read noted that ‘the last piece to be completed by Moore at the time of writing is the Atom Piece of July, 1964’.29 It is probable that Read had only seen the plaster working model when he wrote the first draft of his book in the summer of 1964, although he made revisions to the text a year later, by which point he may have seen a bronze cast. Of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) Read wrote:

The configuration of the piece was suggested by the shape of the cloud that rises after the explosion of an atomic bomb – a beautiful shape, as is often the case with shapes associated with evil or murderous purposes – the shapes of spears, axes swords, etc. This paradox, in which good and evil, beauty and power, unite in one symbol, is fully realized in this unusual piece – unusual because, if I am not mistaken, it is the only piece of sculpture by Henry Moore that is inspired by mechanical forces rather than organic growth ... [nonetheless] in this case the dense dome-like cloud develops into a form similar to the compact bone-structure of the human skull, as if the sculptor were fully aware of this significant correspondence. The lower half of the sculpture is architectural, a series of arched cavities merging into a domed space reminiscent of the inside of a cathedral. The whole concept suggests the containment of a powerful force, in the way that a compact skull holds a brain capable of the wildest fantasies. The Atom Piece symbolizes those forces which modern man has released for ends which cannot yet be imagined or realized, but which for the present we inevitably associate with universal destruction. At the same time it negates this evil intention and returns the contemplating mind to a mood of stillness and serenity.30

For Read, Atom Piece could be understood not only in terms of nuclear explosions and ‘mechanical forces’, but as a humanistic statement in support of ‘modern man’ and positive advances in science. This duality was also noted at the unveiling of the full-size Nuclear Energy at the University of Chicago on 2 December 1967.31 In his address at the ceremony, Harold Haydon, who had been part of the delegation that visited Hoglands in 1963, recognised that ‘nuclear energy, for which the sculpture is named, is a magnet for conflicting emotions, some of which inevitably will attach to the bronze form; it will harbor or repel emotion according to the states of mind to those who view the sculpture’.32 The polarities of beauty and devastation, hope and terror identified in Nuclear Energy were seen to echo the belief that the outcomes of Fermi’s experiment were liable to both positive and negative uses, namely nuclear power and the atomic bomb. These interpretations were supported by Moore’s own statements on the work. In an article published in the summer of 1967, Albert Elsen narrated his discussion with Moore about Atom Piece:

Without amplification, he observed that the smoothness and brilliance of the warm gold patinated bronze was important for the theme. On the contrast between the dome and its supports, Moore did observe that ‘nuclear power is both for good and bad, it is not all destructive. As I worked on the piece, I rationalized to myself what this power would be used for’.33

Over time the dual possibilities of nuclear energy became an explanatory trope for Moore. Echoing Read’s references to a ‘compact skull’ and the interior vaults of a cathedral, in 1977 Moore stated that:

I like the details which show its skull-like top. I meant the sculpture to suggest that it was man’s cerebral activity that brought about the nuclear-fission discovery. I can also suggest the mushroom cloud, the destructive element of the atom bomb.

The lower half of the sculpture has something architectural about it, like the arches of a cathedral or entrances leading into a protective interior, suggesting the valuable and helpful side the splitting of the atom could have for mankind. And there are many other symbolic interpretations to be found in it.34

The lower half of the sculpture has something architectural about it, like the arches of a cathedral or entrances leading into a protective interior, suggesting the valuable and helpful side the splitting of the atom could have for mankind. And there are many other symbolic interpretations to be found in it.34

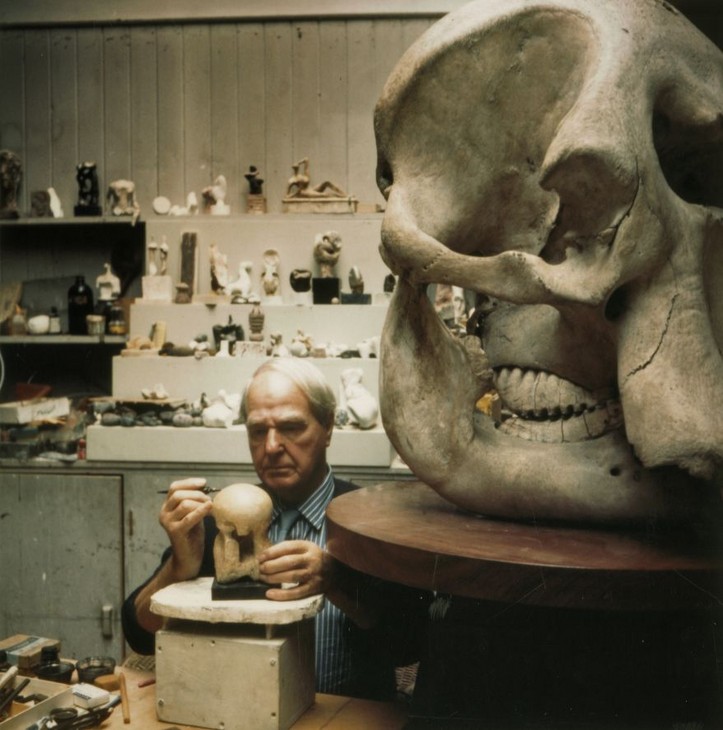

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio, October 1970

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Errol Jackson

Henry Moore in his studio, October 1970

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Lead

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Often my ideas grow from earlier ones and sometimes one of them refers to an initial idea and makes a variation on it. There is no doubt that this, the nuclear energy piece, has connections with previous sculptures that I’ve made which were based on skull forms or on dome-like forms with an interior to them. This piece became a combination of these two ideas. How successful or how much this can be conveyed to other people I don’t know, it’s just my interpretation.40

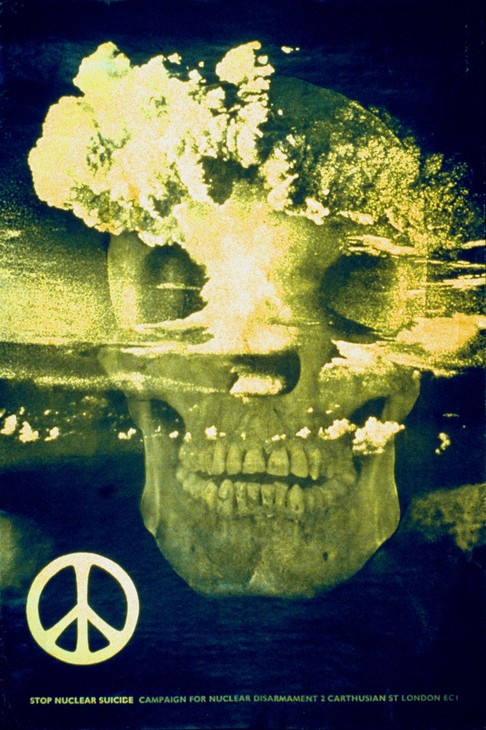

H.K. Henrion

Stop Nuclear Suicide c.1959

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Archive, London

Fig.14

H.K. Henrion

Stop Nuclear Suicide c.1959

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Archive, London

Stephens has suggested that the ambiguous symbolic content of Atom Piece was in keeping with Moore’s attitudes towards military conflict. In 1940 Moore had written to his friend Arthur Sale, who was a conscientious objector, expressing unresolved feelings regarding the war with Nazi Germany:

I can’t say with complete certainty that there aren’t some things I might find myself ready to fight for, & so I can’t call myself a wholy [sic.] consistent conscientious objector. I’d be glad if I could, for I respect greatly the real pacifist point of view, and I’m glad to know that you are a C.O., & will have the courage to remain so.42

In December 1950, in response to growing anxieties over the war in Korea, Moore, along with Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster, Augustus John and others, signed their names to a letter stating that ‘in no circumstances should our country associate itself with the use of atomic weapons against people who have not used them against us’.43 Although the letter called for diplomatic resolutions, Stephens noted that it falls short of calling for complete nuclear disarmament, claiming that Moore ‘drew a distinction between the belligerent use of nuclear power in the atomic bomb and the benign potential of nuclear energy’.44 The art historian Catherine Jolivette has argued that Moore’s Atom Piece not only communicates Moore’s personal ambivalence, but ‘provide[s] a fitting illustration of the complex range of British attitudes towards atomic power’.45

The Henry Moore Gift

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.46 Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) was displayed in gallery twenty-one alongside Working Model for Knife-Edge Two-Piece 1962 (Tate T00603) and Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961 (Tate T02287). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.47 At its close in late August the Director of Tate, Norman Reid, reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.48 After the exhibition Tate decided that it should lend certain works from the Henry Moore Gift to regional galleries in the United Kingdom on a long-term basis.49 Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) was loaned to Bradford City Art Gallery from 1979 to 1981, when it was included in an international touring exhibition around Spain and Portugal.

Other casts of Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) are held in the Didrichsen Art Museum, Helsinki; the John Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore; the Hakone Open Air Museum, Hakone; and the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima. One other cast is believed to be in a private collection.

Alice Correia

September 2013

Notes

Iain A. Boal, ‘Ground Zero: Henry Moore’s Atom Piece at the University of Chicago’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.224.

Henry Moore cited in David H. Katzive, ‘Henry Moore’s Nuclear Energy: The Genesis of a Monument’, Art Journal, vol.32, no.3, Spring 1973, p.286.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, pp.104, 113, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.215.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.211.

Henry Moore, letter to Vice President Daly, University of Chicago, 1 December 1965, Tate Archive TGA 20011/11.

Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, Summer 1967, p.353.

Derek Howarth, ‘Assisting Henry Moore 1964–70’, in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, p.112.

Seam lines usually become more prominent when the metal used to weld the sections together has a different composition to the rest of the bronze.

Henry Moore cited in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, pp.3–4, Tate Archive TGA 200816.

G.S. Whittet, ‘Farewell to Flat, Goodbye to Square: London Commentary’, Studio International, October 1965, pp.169–70.

The sculpture was unveiled at 3:36 pm, the exact time of Fermi’s experiment twenty-five years earlier.

Harold Haydon, ‘The Testimony of Sculpture’, transcript of dedication made at unveiling of Nuclear Energy 1964–6 at the University of Chicago, 2 December 1967, Tate Archive TGA 20011/11.

Chris Stephens, ‘Henry Moore’s Atom Piece: The 1930s Generation Comes of Age’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.250.

Henry Moore, letter to Arthur Sale, 8 October 1938, Imperial War Museum Archive IWM ART 16597 2 a-b, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/19444 , accessed 24 June 2013.

Leslie Banks, Arnold Bax, Adrian C. Boult and others, ‘Use Of Atomic Weapons’, Times, 14 December 1950, p.7.

Catherine Jolivette, ‘Science, Art and Landscape in the Nuclear Age’, Art History, vol.35, no.2, April 2012, p.263.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Henry Moore’s Photographic Identity Marin R. Sullivan

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www