Walter Richard Sickert Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France 1932

Walter Richard Sickert,

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France

1932

This large, elongated canvas is dominated by the radiant figure of the actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, waiting offstage during a rehearsal of the play Edward II by Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593). She wears the Elizabethan costume, pearls and emerald ring of the character of Queen Isabella of France. The inscription ‘La Louve’, or ‘she-wolf’, alludes to Isabella’s ruthlessness. Although Ffrangcon-Davies and Sickert were close friends at the time it was painted, she did not sit for the portrait, which was made from a photograph taken by a professional photographer named Bertram Park.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France

1932

Oil paint on canvas

2451 x 921 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Sickert, p.’ bottom left, ‘BERTRAM/PARK phot.’ bottom right and ‘LA LOUVE’ lower edge.

Presented by the National Art Collections Fund, the Contemporary Art Society and Frank C. Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1932

N04673

1932

Oil paint on canvas

2451 x 921 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Sickert, p.’ bottom left, ‘BERTRAM/PARK phot.’ bottom right and ‘LA LOUVE’ lower edge.

Presented by the National Art Collections Fund, the Contemporary Art Society and Frank C. Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1932

N04673

Ownership history

Bought from R.E.A. Wilson of the Wilson Galleries, London, 1932 by the National Arts Collection Fund, Contemporary Art Society and Frank C. Stoop for presentation through the Contemporary Art Society to Tate Gallery 1932.

Exhibition history

1932

Wilson Galleries, London, September 1932 (no catalogue).

1936

Twee Eeuwen Engelsche Kunst, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, July–October 1936 (138).

1949

Painters and the Theatre, City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, May–June 1949 (158).

1949

Art and the Theatre, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Cheshire, July–September 1949 (202).

1960

Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1960, Southampton Art Gallery, July 1960, Bradford City Art Gallery, July–August 1960 (180).

1981–2

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927–1942, (Arts Council tour), Hayward Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, March–April 1982, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, April–May 1982 (41, reproduced).

1991–2

The Portrait in British Art: Masterpieces Bought with the Help of the National Art Collections Fund, National Portrait Gallery, London, November 1991–February 1992 (66, reproduced).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (114, reproduced as ‘Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France in Marlowe’s Edward II: La Louve’).

1998

James McNeill Whistler, Walter Richard Sickert, Fundación ‘La Caixa’, Madrid, March–May 1998, Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, May–July 1998 (90, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1932

Daily Telegraph, 6 September 1932, reproduced.

1932

Times, 6 September 1932, reproduced.

1932

Apollo, October 1932, reproduced.

1932

‘Sickert’s Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies’, Sketch, 30 November 1932, vol.160, no.2079, p.394, reproduced.

1933

National Art Collections Fund Twenty-Ninth Annual Report 1932, London 1933, p.23.

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, pp.213, 223.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, reproduced pl.47.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.626–7.

1964

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: A Handbook to the Drawings, Paintings, Etchings, Engravings and other Material in the Possession of the Islington Public Libraries, London 1964, [p.3].

1970

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: Catalogue of the Islington Libraries Collection, London 1970, p.6.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.176, no.416, reproduced fig.288.

1975

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, p.36.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.235.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, p.124, reproduced pl.84, as La Louve. Miss Gwen Ffrangçon-Davies as Isabella of France.

1989

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, Liverpool 1989, p.13.

1990

Richard Shone, From Beardsley to Beaverbrook: Portraits by Walter Richard Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath 1990, p.8.

1991

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1991, p.139.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, pp.60–1, reproduced fig.50.

2003

Martial Rose, Forever Juliet: The Life and Letters of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies 1891–1992, Dereham 2003, pp.34, 184.

2004

Alistair Smith (ed.), Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, p.26.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.582, 584–5, 587.

2006

Rebecca Daniels, ‘Newly Discovered Photographic Sources for Walter Sickert’s Theatre Paintings of the 1930s’, Burlington Magazine, vol.147, April 2006, pp.272–3.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, pp.121, 545, no.744, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert painted this work on a coarse-weave jute canvas, similar to that used for Miss Earhart’s Arrival (Tate T03360). The cloth has a very open weave and has been prepared with a white primer, which has penetrated into the cloth leaving many ‘pin-holes’ in the weave interstices. The canvas primer was applied after stretching and covers only the front-face, providing a slightly absorbent and textured ground that facilitated drying and was suited to a large scale working.

The image is known to have been based on a newspaper photograph. The artist’s usual practice of drawing in black paint is not visible in this work, although it may be covered by subsequent layers. The picture was painted methodically using three pinks prepared on the palette and a white for the lights to create the various tones of the composition in a camaieu-type preparation. The photograph was probably squared up for transfer (see also Tate T00221) and used in conjunction with a ‘grille’ (see also Tate T03360). There is a black grid present, not at the lowest level but applied over paint and in turn overpainted in parts. The dark horizontal and vertical lines appear to sag towards the bottom and the application of paint gives the impression of painting up to a physical barrier that follows the grid. In places the lines are also in double register suggesting that the grille was moved. In a letter to his friend Ethel Sands, Sickert described the technique:

Now comes the beauty of a preparation in dead-colour or camaieu & the use of the grille. You can afford to brush very fully as wet and fat as you like all edges into each other losing the forms without fear & in successive coats overlapping and reclaiming as often as you like BECAUSE you pop the grille on & with a wet dark line when the thing is dry you can get back the sharpest & most accurate drawing by means of a grille.1

Paint was applied quite thickly from a loaded brush, diluted for some fluidity and drying to a relatively matt finish. There is little mixing on the surface and no modulation within each application. Most of the white primer has been painted over with just the areas between applications left visible in places. There are small areas of green, yellow and brown but otherwise red/pink dominates the figurative subject against a very dark background. The painting was left unvarnished but the artist has retouched parts to make little pink repairs to the image, which are tonally out of key suggesting that they were applied a little later.

Stephen Hackney

September 2005

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', September 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France 1932 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

The list of celebrities and public figures with whom Walter Sickert was friendly at various points of his life is extraordinary. As a young man he had pursued a career on the stage and had rubbed shoulders with actors such as Henry Irving and Ellen Terry. His love of the theatre remained with him throughout his life, particularly manifesting itself in his devotion to the music hall. During the 1930s, however, when the music hall was in decline, he began to focus his attention on modern theatre and the new generation of up-and-coming actors who would go on to become legends in their own lifetime.

In March 1932 he saw one of these rising stars of the stage, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies (1891–1992, fig.1), in a play called Precious Bane, an adaptation of a popular novel by Mary Webb. With his typical combination of charm and élan he wrote to the actress praising her performance and asking her to lunch with him and his wife. She had never heard of him before but was encouraged to take up the invitation by her mother who was aware of Sickert’s reputation as an important artist. Mrs Ffrangcon-Davies Senior encouraged her daughter to record her impressions of the ‘great’ man in a red leather-bound book. After their first meeting on 7 April at the St Pancras Station hotel Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies described Sickert as looking:

like a rather disreputable old bookmaker, as Cedric Hardwicke would play one – in a plaid suit, with swallow-tailed coat and a grey billycock hat – He has a finely-cut sensitive face with untidy white hair falling all over the place, but withal a great distinction. One would say at once ‘Oh who is that?’ He spoke much and very flatteringly of my work, for which he professes an extravagant admiration, but was very disappointed, so he said to find me so young! ... He is an old man 72, but full of life and sparkle tho’ I fear he drinks too much – consuming the best part of two bottles of champagne at lunch, after which he became a little vague but still very courteous, charming ... He says he is the crowned head of the artistic world, as King George is of England.1

After this first encounter, Sickert’s friendship with the actress grew, lasting for two ‘wonderful’ years during which time he wrote to her almost daily and met with her frequently.2 They enjoyed many excursions together and Sickert entertained his new friend at his home or studio. Ffrangcon-Davies later defined his feelings towards her as ‘one of those violent affections which one sometimes finds a little embarrassing but at the same time very flattering to one’s vanity’.3 It is not known whether the relationship ever extended to anything beyond friendship but their correspondence testifies to the genuine affection and admiration they felt for one another. One of their first public outings together must have been in April 1932 when several of the newspapers published photographs of Sickert accompanying Ffrangcon-Davies and an ‘unknown’ companion (the actress Marda Vanne) to a private view of the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy where Sickert’s painting The Raising of Lazarus was on display. Sickert no doubt relished the frisson of interest shown in his acquaintance with the young actress and further exploited the publicity of the relationship by using the photograph as the basis for a painting, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies and the Artist 1932 (whereabouts unknown).4 Sickert completed the painting in time for it to be exhibited in London in July of that year.5 Several newspapers reproduced both the painted work and the original photograph upon which it was based.6

Subject and style

Inevitably, Sickert also conceived a desire to paint a more memorable individual portrait of Ffrangcon-Davies, but, as he explained to her, he had no desire for her to pose or sit for him.7 Instead, he selected an image from her own album of publicity photographs, showing her as Queen Isabella of France in the play Edward II (published 1594) by Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593). Ffrangcon-Davies had performed the role in a Phoenix Society production at the Regent and Court Theatres in 1923. The photograph was apparently a quick snapshot taken during a dress rehearsal while the actress was waiting in the wings for her stage entrance. The whereabouts of the photograph is now unknown (probably because Sickert never returned it to Ffrangcon-Davies after borrowing it from her album). The photographer, Bertram Park, was the husband of Yvonne Gregory, also a photographer who took many official shots of the actress. Sickert scaled up the image onto a large canvas (8 x 3 feet) and added the inscription ‘Bertram Park phot.’, acknowledging the source for the image. He also added the title ‘La Louve’ (The She-Wolf) along the bottom of the painting, referring to the ruthless character of Queen Isabella who, with her lover Roger Mortimer, deposed and murdered her husband, Edward II, with both perpetrators described in the play as wolves.

In 1923, when she took on the role of Isabella, Ffrangcon-Davies was still making a name for herself. She had achieved a breakthrough with her highly acclaimed performance in The Immortal Hour (1922), but was still primarily known as a singer and was eager to extend her acting repertoire. Isabella in Edward II was one of her first major classical roles, but reviews of her performance were mixed. The critic in the Outlook wrote: ‘Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies was not at all good as Queen Isabella: her realistic sobs and groans were hopelessly out of the proper key.’8 However, the New Statesman was more impressed:

One figure stands out, that of the Queen. I have never seen Miss Ffrangcon-Davies act before and was immensely impressed by the dignity of her performance. She has excellent gesture, a musical voice, and she looked most graceful and finished. But better by far than this she spoke intelligently, as if she realised the meaning and the measure of the words she was speaking. While she was acting one could remember how supremely Marlowe could write.9

The Saturday Review reported that ‘The queen of Miss Ffrangcon-Davies was a beautifully firm piece of work and as good to look upon as a portrait of the Flemish school’.10 Nine years later Sickert evidently also relished the aesthetic quality of the picture of the actress in her elaborate Elizabethan costume, complete with pearl necklaces and a large emerald ring. Ffrangcon-Davies recalled that the dress, which was designed by Grace Lovat-Fraser, was made of gold lamé and that her hair had also been painted gold to match the outfit. The full skirt was flat at the front and back but wide at the sides. Sickert had not seen the play himself and the source photograph upon which the painting was based was a black and white image, so he was required to imagine his own colour scheme for the dress.

Sickert’s painting technique was well established during the 1930s and evidence of the various stages of his regimen is clearly visible in Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France. The artist first transferred the image from the photograph to the canvas using the squaring-up method. The drawn grid of squares can still clearly be seen within the skirt and body of the dress. The composition was then sketched in using a pink underlayer, in varying degrees of depth. A darker tone corresponds to areas of shadow while a lighter tone picks out the highlights. In many areas patches of the underdrawing have been left as an integral part of the final painting. Sickert usually left this first layer to dry for at least a month,11 and it was possibly during this stage in the process that Ffrangcon-Davies dined with the Sickerts at their home on 21 July 1932. She recorded in her diary that the painting was well underway and that Sickert had apparently greatly alarmed his wife, Thérèse Lessore, by returning from the studio with the exhortation, ‘Thank God Gwen’s dry and on the operating table’.12 The lettering appears to have been added shortly after this since a letter of 25 July informed Ffrangcon-Davies that the artist had spent ‘a lovely day with the she-wolf. Got the lettering exactly the right place and right size.’13 In the later stages of the process Sickert added the local colouring for the figure over the bone-dry underpainting. Broadly applied white/cream brushstrokes constitute the texture of the dress while brown and black add definition to the face and torso. Finally, small touches of red and green were added to give the figure some depth and minimal warmth. Sickert was working on the canvas right up until it went on display at the Wilson Galleries in early September 1932. When the critic R.R. Tatlock first saw it at the exhibition he reported that the pigment was still wet.14

Reception

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies was well received by the critics who raved over both its technical qualities and its success as a portrait. Frank Rutter described the limited colour palette as a ‘tour-de-force’, and declared that Sickert had ‘never shown his wonderful mastery of light and shade more completely and brilliantly than in this painting’.15 Similarly Tatlock, writing in the Daily Telegraph, considered it the ‘high water mark’ of the artist’s achievements, ‘better aesthetically than anything achieved or likely to be achieved by any other living artist’.16 He praised the rich painterly quality of the brushwork and the dynamism of the composition. The Times was equally expansive:

To have given the portrait so genuinely monumental a composition, without the slightest sign that it is a miniature greatly enlarged in size, is a most remarkable achievement. It is this grand and statuesque quality in the figure which strikes one immediately ... The handling of the paint is all that we expect of Mr Sickert, and perhaps even more free and brilliant than usual. The colour is equally beautiful, the prevailing brown-pink being quickened with one single note of bright green, and the dull slate black background – perhaps the photograph suggested this – making an unexpected, almost eccentric, but still a successful contrast with the play of colour on the dress.17

John Singer Sargent 1856–1925

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth 1889

Oil on canvas

support: 2210 x 1143 mm; frame: 2500 x 1434 x 105 mm

Tate N02053

Presented by Sir Joseph Duveen 1906

Fig.2

John Singer Sargent

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth 1889

Tate N02053

Photographic source

Amidst the glowing reviews in the newspapers, the Manchester Evening News also published an interview with Ffrangcon-Davies concerning the circumstances of the picture.20 In the article, entitled ‘A Portrait I Never Sat For’, the actress emphasised that the painting was entirely based upon a photographic source. Sickert’s own ready confirmation of the fact was also quoted in a typically teasing statement:

I have made it quite clear by painting ‘Bertram Park Photo’ in a corner of the canvas that the portrait was copied from a photograph. The photographer has done all the ground work for me. He has caught the life and movement of the pose. So he deserves his name in a prominent position. Painting a portrait is like catching a butterfly. I have painted portraits with my subject before me. But it is seldom absolutely satisfactory. Your sitter, particularly if she is a lady, dislikes keeping regular appointments. She is often late. The artist resents his time being wasted. When his subject does arrive she finds it difficult to sit perfectly still for long intervals. Her irritation shows in her face. That expression very often steals into the portrait. I find a document from which to copy a satisfactory way of painting a portrait.21

Comparison of the painting with the original photograph (as reproduced in Vogue, December 1923)22 demonstrates Sickert’s ability to reproduce faithfully a found image and yet also subtly alter the visual emphasis of that image to achieve a new aesthetic effect. In this instance he reduced the background space surrounding the actress, particularly on the right-hand side where the pictorial edge truncates the figure of the queen. She therefore appears to dominate utterly the space she inhabits. The instantaneous, innocuous quality of Park’s photograph of Ffrangcon-Davies self-consciously waiting in the wings is replaced in the painting by a sense of dramatic monumentality and suspense. The actress seems to occupy the character of the scheming queen wholly and her white face and immense dark eyes appear skull-like and ghostly against the darkness of the background. She looks imperious and dangerous, yet beautiful and awe-inspiring. As the art historian David Peters Corbett has pointed out, Sickert’s transformation of the candid neutrality of the photograph into the high tension and sagacity of the painting asserts unequivocal artistic control over an image, which he freely admits was not of his making.23 Sickert’s carefully inserted painted allusion to the role of the photographer Bertram Park is ultimately offset, and even countermanded, by the visibility of his own lines of squaring-up within the figure of the actress. Some of these lines even appear to have been strengthened over the top of the preceding painted layers thereby making transparent the artist’s creative ownership of the image.

Sickert’s use of images derived from photographs has drawn both condemnation and praise from contemporary and subsequent commentators. Despite the critical success of Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France other paintings based upon photographic sources attracted frequent criticism (see, for example, Miss Earhart’s Arrival, Tate T03360). The appropriation of found images and the imitative element of the process represented, to some, evidence of Sickert’s declining creative faculties. Even those whom Sickert counted as friends struggled with the artistic credibility of his later works. The painter William Rothenstein, for example, wrote in his memoirs that ‘the enlargements he [Sickert] makes from photographs of his sitters, of actors and actresses especially, are scarcely worthy of him or of his subjects’.24 He complained: ‘Occasionally one is asked to paint a posthumous portrait from photographs: to me, always an unattractive task. But Sickert delights in painting posthumous presentments of the living!’25 D.S. MacColl similarly thought that Sickert’s photograph-based paintings ought ‘not to be remembered against him’.26 In more recent years, however, the practice has been reinterpreted as a highly original artistic approach, prophetic of the celebrated photograph-based works by such painters as Francis Bacon and Andy Warhol.27

Sickert once said that photography was like alcohol: it should only be used by someone who could do without it.28 His paintings based upon photographic sources are neither artistically inferior nor inherently original. Many artists used photographs as a visual aid to painting, although few admitted to it as openly and readily as Sickert. Throughout his career he struggled with the quest for technical solutions to the problems of making art. He believed he had found the answer to painting by around 1915 and continued to try and persuade artists to follow his scheme throughout his life. In 1934 he lectured to a group of art students: ‘I am going to tell you in about ten minutes of a quarter of hour how to paint and what painting consists of ... You simply use materials which you can buy anywhere and if you know how to use them and use them properly it is very simple.’29 However, he continued to struggle with capturing the essence of a subject in line, through drawing, for the rest of his life. His use of photographs as a compositional and structural basis for painting was a natural progression from his previous reliance on drawings, or as the art historian Rebecca Daniels has described it, a modernisation of the process of sketching.30 He believed that the snapshot photograph captured the same essence of a sitter’s appearance and character as the rapid sketching technique he had endorsed until then. He summarised his opinions in an article of 1929:

A photograph is the most precious document obtainable by a sculptor, a painter, or a draughtsman. Canaletto based his work on tracings made with the camera lucida. Turner’s studio was crammed with negatives. Moreau-Néalton’s biography of Millet contains documentary evidence that Millet found photographs of use. Degas took photographs. Lenbach photographed his sitters. To forbid the artist the use of available documents of which the photograph is the most valuable, is to deny to a historian the study of contemporary shorthand reports. The facts remain at the disposition of the artist. I am for the lean ‘war’ horse.31

The precedent for using photographs in this way is apparent in the work of Sickert’s most revered mentor, Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Sickert was certainly familiar with one portrait by Degas based upon a photograph, Princess Pauline de Metternich c.1865 (National Gallery, London, formerly Tate Gallery),32 which he praised in a catalogue essay of March 1923.33 Degas’s portrait of the wife of the Austro-Hungarian ambassador to Paris is partially based on a photograph by Eugène Disderi used by the subject as a ‘carte-de-visite’.34 In a manner that recalls Sickert’s treatment of the photograph of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, Degas cropped the image (removing the figure of the princess’s husband) and imposed upon the composition an imagined colour scheme and decorative background. The artist has also acknowledged the photographic source of the portrait, deliberately blurring and softening the features of the sitter so that they appear indistinct, as though she has moved during the exposure. Both Sickert and Degas exploited photography as a modern form of image-making but, rather than being slavish imitators of the characteristics of the art, they used it solely as a useful tool at their disposal. They selected or ‘teased’ elements from photographs but always sought to reassert their own artistic dominance over the original source. Sickert compared this process to an actor reinterpreting a role in the theatre.35

Ownership

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France was purchased directly from the Wilson Galleries by the Tate Gallery in 1932. The champion for its inclusion in the national collection was the Tate’s director, James Bolivar Manson, who had known Sickert from his Camden Town Group days. He apparently had to exert his influence to achieve the acquisition, possibly because of Sickert’s controversial use of a photographic source, or perhaps because of the high asking price of £700. Wilson wrote an encouraging letter to Manson thanking him for ‘the really noble efforts you are making to secure the Sickert of Miss Ffrangcon-Davis for your gallery. I hope you will succeed in conquering the opposition.’36 Funds for the painting were raised through the National Art Collections Fund and the Contemporary Art Society, but the deciding factor was a donation by an individual benefactor, Frank Stoop. Stoop was a Dutch businessman based in London who was a keen collector of modern art. Through his generosity the Tate had already received an oil painting by Georges Braque and a number of drawings and sculptures by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. In 1933 he bequeathed an additional seventeen important works by modern European artists, including Degas pastels and the first paintings by Picasso to enter the collection. Ffrangcon-Davies was delighted by the news that her portrait has been bought by the gallery. She sent a telegram to Sickert on 16 December 1932: ‘TERRIBLY HAPPY AND THRILLED THE TATE HAVE GONE TO MY TETE GOING BOURNEMOUTH WEEKEND WITH MOTHER AND WILL WRITE FROM THERE EVER YOURS = LOUVE +’.37

Versions

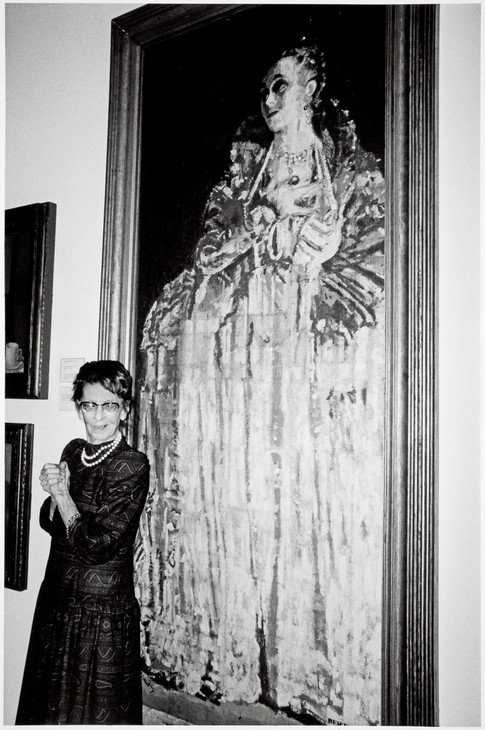

Gwen Ffrangcorn-Davies alongside Sickert's painting 'Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France' 10 March 1989 Photograph taken at the Tate Gallery, London

Photo © Tate

Fig.3

Gwen Ffrangcorn-Davies alongside Sickert's painting 'Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France' 10 March 1989 Photograph taken at the Tate Gallery, London

Photo © Tate

Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies’s acting career lasted over eighty years and in 1991, aged 100, she was made a Dame. Two years earlier, aged ninety-eight she had been invited to the Tate Gallery to be photographed in front of her portrait, an event that was reported in the national press (fig.3).41 On this occasion she was also interviewed by members of Tate staff about her relationship with Sickert and the circumstances surrounding the painting. Her reminiscences were recorded for Tate’s archive.42 She recalled that during her lifetime she had also been painted by Philip de Laszlo (1869–1937)43 and Harold Knight (1874–1961).44 However, she rated Sickert as the greater artist and it was his series of portraits of her that she preferred above all the rest.

Nicola Moorby

September 2005

Notes

Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, 7 April 1932, quoted in Martial Rose, Forever Juliet: the Life and Letters of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, 1891–1992, Dereham 2003, p.59.

Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies recorded interview with Tate Gallery staff, 10 March 1989, Tate Archive TAV 564A.

‘Sickert’s High Steppers’, unpublished manuscript to accompany an exhibition, Tate Archive TGA 881/15, pp.7–8.

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, July–August 1975, p.35.

Cicely Hey, Walter Sickert 1860–1942: Sketch for a Portrait, 10 February 1961, BBC Home Service, LP 26655, Side 1.

Walter Richard Sickert, ‘Engraving, Etching, Etc.’, Lecture at Margate School of Art, 23 November 1934, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.661.

Rebecca Daniels, ‘Richard Sickert: The Art of Photography’, in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, p.27.

Walter Richard Sickert, ‘Artists and the Camera’, Times, 15 August 1929, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.591.

Reproduced at National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/hilaire-germain-edgar-degas-princess-pauline-de-metternich , accessed March 2011.

Walter Richard Sickert, ‘The Sculptor of Movement’, in Exhibition of the Works in Sculpture of Edgar Degas, Leicester Galleries, London 1923, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.457.

Reproduced in David Bomford, Art in the Making: Degas, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London 2004, p.62.

Walter Sickert, ‘Squaring up a Drawing’, Lecture at Margate School of Art, 2 November 1934, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.637.

Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, letter to Walter Sickert, 16 December 1932, Walter Sickert press cuttings, Islington Public Libraries, London, 1915–41.

Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies recorded interview with Tate Gallery staff, 10 March 1989, Tate Archive TAV 564A.

Portrait of Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Mary Queen of Scots 1934. Reproduced in Modern British and Irish Paintings and Drawings, Sotheby’s, London, 13 May 1932 (lot 36).

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, NMW A 592, reproduced at http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/online/?action=show_item&item=1168 , accessed March 2011.

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

- London Narratives in Photography 1900–35 Valerie Williams

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France 1932 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www