Walter Richard Sickert Ennui c.1914

Walter Richard Sickert,

Ennui

c.1914

The central theme of one of Walter Sickert’s best-known works is reflected in its title, roughly translated from the French as ‘boredom’. A man, smoking, and a slump-shouldered woman share the same domestic interior, yet appear psychologically estranged from one another. Sickert provided no resolution for the pair, moral or otherwise, causing the writer Virginia Woolf to attribute Ennui’s ‘grimness’ to the fact that ‘there is no crisis’.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui

c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

1524 x 1124 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert.’ in black oil paint bottom right

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03846

c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

1524 x 1124 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert.’ in black oil paint bottom right

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03846

Ownership history

New English Art Club, London, Summer 1914 (164), where bought by the Contemporary Art Society and presented to Tate Gallery 1924.

Exhibition history

1914

Fifty-First Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists, London, Summer 1914 (164).

1914

Special Exhibition of Modern Paintings in Oil and Watercolours Lent by the Contemporary Art Society, London, Belfast Art Gallery and Museum, November 1914 (17).

1915

The Society of Twelve: Eighth Exhibition, P. & D. Colnaghi & Obach, London 1915 (6, reproduced).

1916

Paintings by Walter Sickert, Carfax Gallery, London, November 1916 (22).

1917

The Society of Scottish Artists, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, December 1917 (no catalogue found).

1923

Contemporary Art Society Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Grosvenor House, London, June–July 1923 (113).

1935–6

61st Autumn Exhibition, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, October 1935–June 1936 (80, reproduced).

1938

Exhibition of British Painting, Musée de l’Orangerie and Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, March–May 1938 (233).

1939

Contemporary British Art, British Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, April–October 1939 (113, reproduced).

1939–40

Contemporary British Art from the British Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, (British Council tour), National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, December 1939 (113), Toronto Art Gallery, Toronto, January 1940, Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, February 1940, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, May–September 1940 (113, reproduced), Arts Club, Chicago, November 1940 (56), Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, December 1940 (82, reproduced).

1940–5

Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, until c. December 1945 (long loan).

1956–7

Masters of British Painting, 1800–1950, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October–December 1956, City Art Museum of St Louis, January–March 1957, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, March–May 1957 (82, reproduced).

1960

The First Fifty Years: 50th Anniversary Exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, London, April–May 1960 (70, reproduced).

1960

Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1960, Southampton Art Gallery, July 1960, Bradford City Art Gallery, July–August 1960 (124).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (12, reproduced).

1991–2

British Contemporary Art 1910–1990: Eighty Years of Collecting by the Contemporary Art Society, Hayward Gallery, London, December 1991–January 1992, Maclaurin Art Gallery, Ayr, February–March 1992, City Museum and Art Gallery, Bristol, March–May 1992, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, May–June 1992 (no number, reproduced p.39).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (80, reproduced p.231).

1998

Two British Impressionists: Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, Norwich Castle Museum, January–April 1998 (26, reproduced).

2004

Strangers, New Art Gallery, Walsall, February–April 2004 (no number, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (26, reproduced).

2004–5

Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, October–December 2004, Southampton City Art Gallery, January–March 2005, Ulster Museum, Belfast, April–June 2005 (5.01, reproduced).

2005–6

Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, Tate Britain, London, October 2005–January 2006, The Phillips Collection, Washington, February–May 2006 (111, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (50, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1920

Contemporary Art Society Report 1914–1919, London 1920, p.4, reproduced pl.3.

1921

Theodore Galerien, ‘The Renaissance of the Tate Gallery’, Studio, vol.82, no.344, November 1921, p.194.

1925

Queen, 26 August 1925, reproduced.

1930

Joseph Duveen, ‘Thirty Years of British Art’, Studio, London 1930, reproduced p.43.

1930

Bernard Falk, ‘Richard Sickert: The Most-Discussed Artist of the Day’, Daily Mail, 12 May 1930, reproduced.

1934

Virginia Woolf, Walter Sickert: A Conversation, London 1934, pp.13–15, 25.

1937

Sickert and the Living French Painters, exhibition catalogue, Adams Gallery, London 1937, [p.3].

1939

John Rothenstein, ‘Walter Richard Sickert’, Picture Post, 18 February 1939, reproduced.

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, p.139.

1941

Sickert, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London 1941, p.9.

1943

Lillian Browse and R.H. Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, pp.29, 53.

1948

John Russell, From Sickert to 1948, London 1948, p.107, reproduced pl.5.

1950

Some 20th Century English Paintings and Drawings: W.R. Sickert, P.W. Steer, Duncan Grant, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council of Wales, Cardiff 1950, p.22.

1950

Allan Gwynne-Jones, Portrait Painters. European Portraits to the End of the Nineteenth Century and English Twentieth-Century Portraits, London 1950, p.31, reproduced pl.130.

1951

Sickert: Forty of his Finest Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Roland, Browse and Delbanco, London 1951, p.6.

1951

Anthony Bertram, A Century of British Painting 1851–1951, London 1951, p.69, reproduced pl.23.

1952

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, pp.54–5.

1953

Sickert 1860–1942, exhibition catalogue, The Scottish Committee of the Arts Council, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh 1953, p.5.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, pp.6, 9, reproduced pl.28.

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield 1957, p.14.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.31, 78, 102.

1960

Sickert: Centenary Exhibition of Pictures from Private Collections, exhibition catalogue, Agnew’s, London 1960, p.53.

1961

John Rothenstein, Sickert, London 1961, [p.24], reproduced pl.11.

1964

Sickert 1860–1942: An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, Northampton Art Gallery 1964, p.5.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.623–4.

1967

Ronald Pickvance, Sickert, London 1967, reproduced front cover.

1967

David Sylvester, ‘Walter Sickert: More about the Englishness of English Art’, Artforum, vol.5, no.9, May 1967, p.43.

1970

Our Own Sickerts: An Exhibition of Drawings, Paintings and Etchings from the Collection of Islington Libraries, exhibition catalogue, Islington Libraries, London 1970, p.3.

1970

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: Catalogue of the Islington Libraries Collection, London 1970, p.3.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, p.47.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.142–44, 155, 186–7, no.313, reproduced fig.223.

1974

Charles Harris, Islington, London 1974, p.189.

1975

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Late Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, p.36.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, pp.150–1, 176.

1977

Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull 1977, pp.22, 24–5, 38–9, 44–5, 60, reproduced p.25.

1977

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.218.

1978

Louise Collis, ‘Sickert’, Art and Artists, vol.12, no.11, March 1978, p.30.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, pp.111–2, reproduced fig.14.

1981

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, p.16.

1983

Linda Gillard, ‘The Artist who Painted Jack the Ripper’, Reader’s Digest, April 1983, pp.52–3.

1985

David Bindman (ed.), The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of British Art, London 1985, reproduced p.246.

1987

David Withey, The Sickerts in Islington, exhibition catalogue, Islington Libraries, London 1987, p.2.

1988

Diane Filby Gillespie, The Sisters’ Arts: The Writing and Painting of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, New York 1988, pp.96–8, reproduced fig.2.9.

1988

Richard Shone, Walter Sickert, Oxford 1988, pp.56, 60, 110.

1988

Laura Wortley, British Impressionism: A Garden of Bright Images, London 1988, reproduced p.239.

1990

Jean Overton Fuller, Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, Oxford 1990, pp.11, 63–6, 70.

1991

Alan Bowness, Judith Collins, Richard Cork et al., British Contemporary Art 1910–1990: Eighty Years of Collecting by the Contemporary Art Society, London 1991, pp.49, 53 n.45, 146, reproduced p.39.

1991

Bernadette Nelson, The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1991, p.12.

1994

Eredità dell’impressionismo 1900–1945: La realtà interiore, exhibition catalogue, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome 1994, p.171, reproduced fig.1, p.169 (detail).

1994

Eric Shanes, Impressionist London, New York, London and Paris 1994, p.158, reproduced pl.131.

1995

Stella Tillyard, ‘The End of Victorian Art: W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, New Haven and London 1995, pp.192, 200, 202, reproduced fig.37.

1996

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996, p.35.

1996

Susan Sidlauskas, ‘Pysche and Sympathy: Staging Interiority in the Early Modern Home’, in Christopher Reed (ed.), Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, London 1996, p.67, reproduced fig.19, p.68.

1998

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionnisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998, p.37.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.98, 205.

2000

Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, p.29, 181, reproduced fig.8.

2000

Susan Sidlauskas, Body, Place, and Self in Nineteenth-Century Painting, Cambridge and New York 2000, pp.124–149, reproduced fig.47 and pl.VIII.

2000

Lisa Tickner, Modern Life and Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, New Haven and London 2000, p.8.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, p.34, reproduced fig.27 and frontispiece, p.2 (detail).

2001

James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain During the Cold War 1945–1960, New Haven and London 2001, p.39, reproduced pl.32.

2001

Exposed: The Victorian Nude, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2001, p.265.

2002

Patricia Cornwell, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed, London 2002, pp.109–110, 356, reproduced opposite p.197.

2003

Wendy Baron, ‘The Many Faces of Dora Sly’, Burlington Magazine, vol.145, no.1204, July 2003, p.517.

2003

Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London 2003, p.118.

2004

Vision 2004, Lakeland Arts Trust, Kendal 2004, p.10, reproduced.

2004

Nicola Moorby, ‘“A long chapter in the ugly tale of common-place living”: The Evolution of Sickert’s “Ennui”’, in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, pp.11–14, reproduced fig.5.01, p.114.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.436, 498, 631, reproduced in between pp.544–5.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, pp.95–6, 139, 408–9, no.418, reproduced.

2008

Kenneth McConkey, The New English: A History of the New English Art Club, London 2008, p.119, reproduced p.121, fig.98.

2011

William Rough, ‘Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama’, The Camden Town Group, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk.

Technique and condition

Sickert chose a large portrait-format canvas from the artists’ colourmen L. Cornelissen & Son. The linen cloth is of good quality with an open plain weave and double threads in each direction, producing a coarse-textured canvas, which has been prepared with an absorbent ground in an animal glue medium, perhaps made especially for Sickert. It would have provided a lean textured surface that facilitated the drying of the applied paint, enabling him to build up layers without them becoming medium-rich and overworked (see Tate N05092).

Sickert normally worked on a small scale directly related to the dimensions of the subject as seen by the artist, but this version of Ennui is unusual in being a larger, scaled-up image of the type that the artist was exploring at this stage. Despite the large size of the image, on the canvas there is no visible evidence of squaring-up or drawing, although it is possible that he drew in chalk that is no longer visible. It is also probable that he used a ‘grille’to match the squared-up drawing.

Sickert painted in oil directly on to the white primer with no imprimatura or modification. He appears to have initially applied diluted washes of light and low colour tone to demarcate the composition. He used this application to define his shadows as warm and his lights as cool, indicating an indoor scene, with the exception of the blue blouse. He then worked over the entire painting to refine and modify the composition using opaque paint throughout, painting across the forms utilising the absorbency of the lean underlying paint and ground layers and exploiting the added control that came from the broader scale of the composition. The paint varies in thickness with a few strongly brushed parts that have significant impasto texture, sometimes not directly related to forms and revealing minor reworking of the image. In other parts lean paint has been applied to skip over the canvas tops leaving broken strokes, characteristic of Sickert’s ‘unfinished’ aesthetic. The table with its horizontal brushed strokes of two brown paints, light and dark, is an example of an area left as a minimally resolved impression. The painting has been varnished with a thin brushed coat to create a smooth glossy surface, which has now yellowed; its removal would restore the lean unevenness of the paint application.

Stephen Hackney

October 2006

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', October 2006, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Ennui c.1914 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

In June 1914 the art connoisseur, collector and curator of the Holbourne Museum, Bath, Hugh Blaker (1873–1936), published a letter in the Observer highlighting the display at the New English Art Club of one of ‘the finest pictures painted in England in recent times ... It is one of those precious things the ultimate destination of which is a public gallery, and I suggest that the [Chantrey Bequest] trustees give it their serious consideration.’1 Blaker was not alone in his admiration of the work which was almost immediately purchased for the nation, not under the auspices of the Chantrey Bequest but through the Contemporary Art Society. This painting, eventually presented to the Tate Gallery in 1924, was Ennui, which has become the most well-known and widely discussed image of Sickert’s oeuvre.

The basis for the reputation of Ennui is somewhat unclear. As the art historian Wendy Baron has pointed out, Tate’s version of Ennui is uncharacteristic of Sickert’s work during this period because of its large size. Part of its fame can certainly be attributed to the multiple versions of the image. Tate’s painting is considered to be the principal manifestation of the subject, and is also the largest and most highly finished example. However, the familiarity of the picture rests with a further four painted versions, a host of drawings and preparatory studies and three etched plates in various sizes, indicating that Sickert himself considered it an important subject worthy of repetition. Although it is not possible to ascertain the exact date order of the paintings, Baron has argued that two appear to be small preliminary oil studies for Tate’s version dating from 1913.2 Both of these, Ennui c.1913 (Royal Collection)3 and Ennui c.1913 (James Saunders Watson, Rockingham Castle, formerly in the possession of Dr A.S. Cobbledick),4 are broadly executed, cropped studies showing the same male and female figures but omitting the table in the foreground. A further Ennui (private collection)5 is a small oil on canvas inscribed by Sickert to the French painter Maurice Asselin (1882–1947) and dated 1916. The composition is adapted from Tate’s earlier, large painting and shows the seated male with the figure of the woman, visible only to the shoulders, behind him.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui 1917–18

Oil paint on canvas

760 x 560 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui 1917–18

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The fifth painting in the Ennui series is a later reworking of Tate’s version executed on a half-scale (fig.1).6 Baron has dated the work c.1914–16,7 although Richard Shone has suggested 1917–18.8 Although compositionally similar, the painting is brighter in colour and Sickert has transformed the blank walls and table with patterned surfaces. This, combined with its reduced size, has the effect of making the interior appear more claustrophobic, and many critics have described it as more successful than the original.9

Subject

Tate’s version of Ennui is the culmination of a series of images made between c.1912 and 1914 depicting a male and female figure within an interior (see, for example, fig.2). The painting shows a portly man dressed in a brown suit leaning back in his chair and smoking a cigar, with his gaze lost in the distance. His expression has been interpreted as one of ‘placid contentment’,10 but it could also signal profound apathy and hopelessness. Standing behind him, locked within the same pictorial space, is a plump woman in a simple skirt and blouse. She is slumped against a chest of drawers, leaning on her arms so that her face is partially hidden, staring blankly in front of her. The physical proximity of the two figures supposes an intimate connection between them such as marriage, but their complete disassociation and lack of engagement with one another creates an atmosphere of isolation, indifference and loneliness. Sickert had previously explored the tensions apparent in the domestic arena in works such as Off to the Pub c.1912 (Tate N05430, fig.3), Sunday Afternoon c.1912–13 (fig.4) and Jack Ashore c.1912–13 (fig.5), but none of these portray a situation as explicitly dysfunctional as Ennui.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for ‘Ennui’: Hubby and Marie c.1913

Pen and brown ink over black chalk, with red ink, on pale brown paper

380 x 280 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for ‘Ennui’: Hubby and Marie c.1913

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Off to the Pub 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 695 x 595 x 45 mm

Tate N05430

Presented by Howard Bliss 1943

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Off to the Pub 1911

Tate N05430

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Sunday Afternoon c.1912–13

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 305 mm

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery / The Beaverbrook Foundation (in dispute, 2004)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Sunday Afternoon c.1912–13

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery / The Beaverbrook Foundation (in dispute, 2004)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Jack Ashore c.1912–13

Oil paint on canvas

380 x 305 mm

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (Wilson Gift through The Art Fund, 1985)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Pallant house, Chichester, Sussex, UK (Wilson Gift through The Art Fund) / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

Jack Ashore c.1912–13

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (Wilson Gift through The Art Fund, 1985)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Pallant house, Chichester, Sussex, UK (Wilson Gift through The Art Fund) / The Bridgeman Art Library

It was the Ashmolean version of Ennui that inspired the writer Virginia Woolf’s famous description in her essay Walter Sickert: A Conversation, although the spirit of the passage could equally apply to Tate’s picture. The essay, published in 1934, takes the form of an imaginary dinner party conversation about Sickert’s exhibition at Agnew’s the previous year. Woolf uses Ennui as an example of the literary, novelistic aspect of the painter’s work:

You remember the picture of the old publican, with his glass on the table before him and a cigar gone cold at his lips, looking out of his shrewd little pig’s eyes at the intolerable wastes of desolation in front of him? A fat woman lounges, her arm on a cheap yellow chest of drawers, behind him. It is all over with them, one feels. The accumulated weariness of innumerable days has discharged its burden on them. They are buried under an avalanche of rubbish. In the street beneath, the trams are squeaking, children are shrieking. Even now somebody is tapping his glass impatiently on the bar counter. She will have to bestir herself; to pull her heavy indolent body together and go and serve him. The grimness of that situation lies in the fact that there is no crisis; dull minutes are mounting, old matches are accumulating and dirty glasses and dead cigars; still on they must go, up they must get.11

Woolf’s imagined scenario takes the liberty of interpreting details within the painting and attributing significance to them for which there is no corroborating evidence. There is no basis, for instance, for claiming that the male figure is a publican. However, the importance of Woolf’s text resides in the fact that she recognises the true focus of the painting as the portrayal of a psychological state. Although the descriptive, realist nature of Sickert’s painting allows scope for narrative interpretation, the ambiguity of the scene ultimately discourages the development of a story. The viewer is not meant to piece together a plot or, as in Victorian narrative painting, divine the outcome of the scene driven by a moral agenda. This was ascertained by the critic of the Observer who wrote in 1914:

The incident counts for nothing – the mood is all important. And this mood, the hopeless dreariness of the milieu, the consciousness of the impossibility of escape, the terror which a monotonous commonplace existence in repulsive company must hold for a woman who has realised its emptiness – and all this is expressed with directness and rare intensity.12

Ennui is the visual definition of the emotional state indicated in the title. The literal meaning of the French word ‘ennui’ is ‘boredom’, but there is a certain amount of slippage between the two terms and some of the sense is lost in translation. The significance of the choice of a French title for Ennui deserves serious consideration. Wendy Baron has observed that it is unusual for one of Sickert’s titles to so precisely express the content of the image.13 The relationship between his works and their titles is a complex aspect of his art. In an article for the New Age in 1910, Sickert wrote that he viewed titles as practical necessities since pictures ‘like streets and persons, have to have names to distinguish them’.14 However, he questioned the value of titles as descriptive vehicles through which to view a work, believing that the ‘subject is something much more precise and much more intimate than the loose title that is equally applicable to a thousand different canvases’.15 He frequently chose to bestow upon a painting a suggestive title that seems to encourage a certain interpretation, yet on other occasions he created obscure titles that confuse rather than clarify meaning. At times paintings were exhibited under different titles, reinforcing the ambiguity of the image and discouraging a narrative reading, for example, The Camden Town Murder Series No.1 (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund)16 was also known as Summer Afternoon and What Shall We Do For The Rent?. This has been interpreted as the prioritisation of visuality over subject matter, and evidence that Sickert’s visual objects should not be defined by their titles.17

Yet although Sickert could be mischievous when naming his works, he was never capricious. Like his one-time mentor, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Sickert was an extremely articulate and erudite man for whom the skilful and precise use of language was an important characteristic. He was one of the most entertaining raconteurs of his day and a prolific writer and art critic. The painter William Rothenstein described him as ‘a finished man of the world. He was a famous wit; he spoke perfect French and German, very good Italian, and was deeply read in the literature of each. He knew his classical authors, and could himself use a pen in a masterly manner.’18 Sickert’s articles, correspondence and even the titles for his paintings are littered with phrases and expressions borrowed from other languages. This is not an arbitrary affectation but a deliberate attempt to use sophisticated language best suited to the nuances of the writer’s theme and expression. When the meaning could not quite adequately be conveyed in English, Sickert employed French, German, Italian and sometimes even Latin or Greek. The choice of the title ‘Ennui’ was a deliberate move calculated to focus and engender meaning. Baron has argued that the name, Ennui, was an afterthought, a by-product of the formal arrangement of the figures within the painting.19 However, this does not take into account the important resonance of the contemporary notion of ‘ennui’, nor Sickert’s protracted efforts to convey that notion effectively. The term has an important literary context which carries with it a host of associations and subtleties of meaning not adequately conveyed when read just as ‘boredom’.

The 1913 edition of Webster’s dictionary defines ennui as ‘a feeling of weariness and disgust, dullness and languor of spirits, arising from satiety or want of interest; tedium’. The etymological root for the word derives from the Latin ‘inodiare’, meaning to hold in hatred.20 Ennui is a state signifying hatred or disinterest in life itself, a ‘state of emptiness that the soul feels when it is deprived of interest in action, life and the world, a condition that is the immediate consequence of the encounter with nothingness, and has an immediate effect, a disaffection with reality’.21 Woolf in her text describes this as ‘the intolerable wastes of desolation’. It is a sinister and totalising malady that affects both the body and the soul. Boredom, by contrast, is a temporary state arising from external circumstances such as enforced inactivity, monotonous, repetitive labour or lack of mental stimulation. Reinhard Kuhn has discussed how boredom can be confused with ennui because the two states present similar symptoms, yet they are nonetheless different.22 Boredom is alleviated by a change in external circumstances while ennui is more pervasive, insidious and not so easily banished. In her discussion of boredom in literature, Patricia Meyer Spacks writes, ‘Ennui implies a judgement of the universe, boredom a response to the immediate’.23

Ennui was a recurring theme running through French literature and poetry of the nineteenth century, both as a subject and a symptom. It afflicts the protagonists of the novels A vau l’eau (With the Current) (1882) by J.K. Huysmans and Madame Bovary (1857) by Gustave Flaubert. It was also an important preoccupation in Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil), first published in 1857. The poet, who also uses the English word ‘spleen’, identifies ennui as a soul-deadening spiritual condition, personifying it as a ‘delicate’ but deadly monster:

Il en est un plus laid, plus méchant, plus immonde!

Quoiqu’il ne pousse ni grands gestes, ni grands cris,

Il ferait volontiers de la terre un débris

Et dans un bâillement avalerait le monde;

C’est l’Ennui! – l’oeil chargé d’un pleur involontaire,

Il rêve d’échafauds en fumant son houka.

Quoiqu’il ne pousse ni grands gestes, ni grands cris,

Il ferait volontiers de la terre un débris

Et dans un bâillement avalerait le monde;

C’est l’Ennui! – l’oeil chargé d’un pleur involontaire,

Il rêve d’échafauds en fumant son houka.

(One creature only is most foul and false!

Though making no grand gestures, nor great cries

He willingly would devastate the earth

And in one yawning swallow all the world;

He is Ennui! With tear-filled eye he dreams

Of scaffolds, as he puffs his hookah.)24

Though making no grand gestures, nor great cries

He willingly would devastate the earth

And in one yawning swallow all the world;

He is Ennui! With tear-filled eye he dreams

Of scaffolds, as he puffs his hookah.)24

Ennui, therefore, existed as a powerfully expressive notion through the work of Baudelaire and other influential writers of the later nineteenth century with whose work Sickert was undoubtedly familiar. His annexation of the term recalls this tradition and raises his scene beyond the level of the domestic to the universal. Ennui transposes the resonance and power of the nineteenth-century idea to contemporary life so that the situation which Sickert depicts in his painting reflects more than just the tedium of a stale relationship: it is a pictorial illustration of two people facing what Baudelaire describes as ‘tout entière au gouffre de l’Ennui’ (Ennui’s most profound abyss), a life bereft of meaning and hope.25 Sickert introduces this psychological state as a symptom of modern urban life prevalent amongst the under-privileged working and lower middle classes. The idea that alienation and depression were an urban malaise is a concept present in the work of Edgar Degas. As the art historian Eric Shanes has pointed out, the dejected postures of the figures, their non-interaction and the vacant foreground space present in Ennui recalls Degas’s painting L’Absinthe c.1876 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).26

Many of the nineteenth-century writers who took ennui as their subject also experienced it themselves, for example Baudelaire, Flaubert, Théophile Gautier, Jules Laforgue, Stéphane Mallarmé, Guy de Maupassant and Paul Verlaine. In an attempt to escape the horror of ennui, many of these poets and writers turned to artificial sensory stimulants, which provided temporary release from the terrible meaninglessness they experienced. The late nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of what came to be termed ‘Decadence’, creativity driven by excess and experimentation, often resulting in debauched, subversive behaviour. In 1892 Punch published a satirical cartoon Post-Prandial Pessimists by George du Maurier, which the art historian Matthew Sturgis has identified as a concise portrait of the ‘decadent type’.27 Two world-weary young men lounge in chairs drinking coffee, ‘resignedly aware that pleasures were but a fleeting respite from the grand futility of existence’.28 Ennui echoes, in some respects, the perceived characteristics of the decadent type. Many critics have noted that by comparison with the woman’s dejected torpor, the central male figure of Tate’s version appears complacent and egocentrically self-absorbed. Nevertheless, there is an element of escapist inertia in his demeanour. He reclines in a parody of bohemian languor indulging in the stereotypical vices of a self-destructive decadent lifestyle, drink and drugs, here tempered by the limitations of a tame petit-bourgeois lifestyle. The stimulants on offer are not opium and absinthe but a cigar, a beer glass half-filled with a liquid which might just be water, and a decanter of red wine or port on the mantelpiece.

Social realism and influence

The novelty of Sickert’s vision of ennui lies with the social circumstances of the sufferers, who are portrayed as lower middle or working class. His images of Ennui were variously described by contemporary critics as evoking the realism of certain French writers: ‘the quintessence of a Balzac translated into paint’,29 ‘peculiarly reminiscent of Zola’,30 and having ‘atmosphere and mood synthesised with a Maupassant-like power’.31 The reviewer of the Pall Mall Gazette in 1914 referred to the painting as ‘a long chapter from the ugly tale of commonplace living’.32 All of these references recall the uncompromising social realism of Sickert’s vision and the observation of human drama within everyday modern life. The models for the man and woman in Ennui were Hubby and Marie, who appear in many of Sickert’s paintings of Camden Town interiors, although they were not a couple in real life. Their larger-than-life personalities and corporeal appearance are so colourful that they could almost be believed to be products of the Sickertian imagination. Hubby, whose real name is unknown, was an old schoolfellow who had fallen into alcoholism and petty crime. According to Sickert’s friend Marjorie Lilly, this ‘casual vagrant’ had turned up at the painter’s studio in Granby Street with nothing except a stolen suitcase.33 Sickert delighted in his ‘kind silly old face & his sympathetic pomposity’,34 and employed Hubby as a man-of-all-work and model. The arrangement initially worked satisfactorily, and between 1911 and 1914 Hubby appears as the male protagonist in numerous paintings and drawings of interiors with figure subjects including Off to the Pub c.1912 (Tate N05430, fig.3). In the summer of 1914, however, Sickert wrote to his friend Nan Hudson:

I am somewhat shaken by the necessity I have been under of breaking my arrangement with poor old Hubby. I thought I held him tight by paying the missus. But I found he was getting money by other sources and he took to arriving silly-drunk which so far from being useful to me upset my whole day’s work & my nerves & makes my heart beat with anger and pity ... Of course it means drink and, eventually prison. I have staved it off for a couple of years that is all.35

Hubby’s female counterpart was Marie Hayes, Sickert’s charlady whom the artist liked to paint for her ‘splendid opulence’.36

The location of Ennui is Sickert’s studio in Granby Street, off the Hampstead Road, Camden Town, which Sickert has carefully manipulated like a stage set to create the right environment.37 In the eighteenth century the writer and politician Horace Walpole wrote about William Hogarth’s satirical images of contemporary life: ‘The very furniture of his rooms describe the characters of the persons to whom they belong.’38 Sickert succeeds in recreating a similarly descriptive environment in Ennui. The tawdry yellow décor, cheap furniture and unfashionably ornate fireplace provide instantly recognisable indicators regarding the social status of the room’s inhabitants. A number of items in the room were studio props that appear in other works by Sickert. For example, the painting of the bare shouldered woman hanging in the background, believed by some to be Queen Victoria, also features in a drawing entitled Degas at New Orleans (private collection),39 and in another oil painting Telling the Tale 1914 (private collection).40 Similarly, the glass domed bell-jar of stuffed birds, a remnant of Victorian taste, is also evident in Marie, an etching of c.1919, a drawing titled Woman Lying on a Couch c.1912 (University of Reading),41 and Les Oiseaux (whereabouts unknown) by Maurice Asselin, the French artist who used Sickert’s studio on occasions.42

The interior depicted in Ennui not only provides a backdrop against which the human inhabitants are defined but also plays an important role in creating the tense, bleak atmosphere of the unhappy pair. The furniture completely encircles and encloses the figures, hemming them into their domestic space so that there is a sense of imprisonment and claustrophobia, echoed by the stuffed birds in the glass dome. The unusual, destabilising angle at which the table is viewed makes it look as though it is tipping up, and the beer glass and matchbox, although technically the correct size for the perspective, seem disproportionately large. The painting’s palette, dominated by yellow, orange, green and brown, invests the room with an unhealthy, nauseous air. As a visual object the painting therefore replicates some of the physical symptoms of the state of ennui: distortion of time and space, immobility and a view of existence with the meaning and beauty filtered out.43

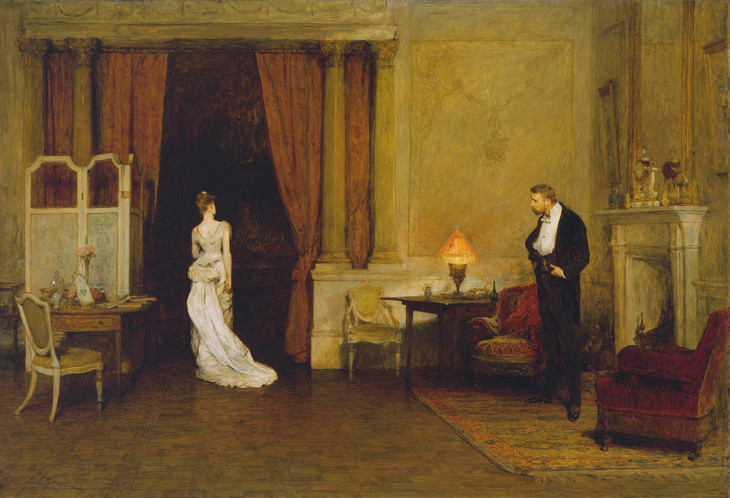

Sir William Quiller Orchardson 1832–1910

The First Cloud 1887

Oil on canvas

support: 832 x 1213 mm

Tate N01520

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Fig.6

Sir William Quiller Orchardson

The First Cloud 1887

Tate N01520

Scale and legacy

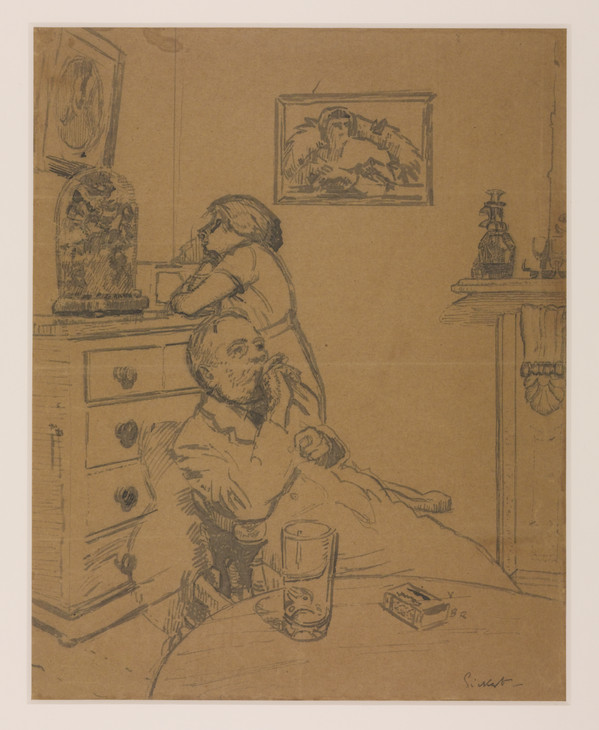

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'Ennui' 1913–14

Ink on paper

support: 419 x 340 mm; frame: 605 x 505 x 20 mm

Tate T00350

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© Tate

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'Ennui' 1913–14

Tate T00350

© Tate

Unusually, Sickert also employed the design of the ‘Ennui’ figures to decorate a Wedgwood plate, inscribed with the words ‘VICINIQUE PECUS’ (A Neighbour’s Flock).55 Apparently only two of these plates were made, one of which was in the possession of the Slade School of Fine Art teacher, Henry Tonks. The other, owned by Colonel Whitwell, was donated in 1923 to the Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzberg, where it remains today.

The potency of the Ennui motif was perpetuated by Ruskin Spear in his painting, Ennui 1941 (With Apologies to Walter Sickert) 1942 (destroyed).56 A newspaper lying in the foreground on a table reveals that Spear transposed Sickert’s couple to 1941 when London was experiencing continual enemy bombardment during the Blitz. The side of their room dissolves into rubble revealing a street of terraced houses and billboards displaying war posters. In the context of the Second World War the couple’s perpetual tedium becomes symbolic of the apparent endlessness of the conflict. Spear belonged to a generation of artists working in the social-realist tradition inherited from Sickert and in 1951 became president of the London Group, the enduring independent exhibiting platform which had evolved from the Camden Town Group. Like Sickert, Spear’s early work drew inspiration from the seedier, poorer areas of London and used a similarly low-toned palette.

Nicola Moorby

May 2004

Notes

Reproduced in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992 (80); Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.418.2.

Reproduced in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004, no.5.05; Baron 2006, no.418.1.

Reproduced in Modern British and Irish Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Sotheby’s, London, 20 November 1991 (lot 112); Baron 2006, no.418.3.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Language of Art’, New Age, 28 July 1910, p.300, in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.264.

William Rothenstein, Men and Memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein 1872–1900, London 1931, pp.167–8.

Reinhard Kuhn, The Demon of Noontide: Ennui in Western Literature, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, p.13.

Patricia Meyer Spacks, Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind, Chicago and London 1995, p.12.

Reproduced in Matthew Sturgis, Passionate Attitudes: The English Decadence of the 1890s, London 1995, between pp.212–13.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands, undated [Summer 1914], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.8.

For more on this, see William Rough, ‘Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama’, The Camden Town Group, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk .

Reproduced in Modern British and Irish Paintings and Drawings, Sotheby’s, London, 2 May 1990 (lot 48); Baron 2006, no.419.

Reproduced in Modern British and Irish Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Sotheby’s, London, 2 October 1996 (lot 56); Baron 2006, no.421.

Stella Tillyard, ‘The End of Victorian Art: W.R. Sickert and the Defence of Illustrative Painting’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, New Haven and London 1995, p.195.

Susan Sidlauskas, Body, Place and Self in Nineteenth-Century Painting, Cambridge and New York 2000, pp.128, 139 and reproduced in Allen (ed.) 1995, fig.36.

Related biographies

Related essays

- After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930 Martin Hammer

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

- Walter Sickert and Contemporary Drama William Rough

- From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group Juliet Kinchin

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

- The Camden Town Group: Then and Now Ysanne Holt

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘The Language of Art’ The New Age, 28 July 1910, pp.300–1.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Ennui c.1914 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www