Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior

Nicola Moorby

Camden Town paintings often featured women within domestic settings but members of the group refused to admit women artists. Nicola Moorby contrasts the group’s attitudes towards women and the domestic sphere with the approach shown by two women artists of the period, Ethel Sands and Vanessa Bell.

One of the recurring themes that characterises the art of the Camden Town Group is that of women and the domestic interior. Most evident in paintings by Walter Sickert, Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore, Malcolm Drummond and William Ratcliffe, the Camden Town ‘house style’ includes a compendium of familiar and homely items such as iron bedsteads, heavy floral furnishings, crockery, pianos, hats and mantelpiece bric-a-brac, as well as numerous female models, wives, lovers, friends, relatives and employees. None of these motifs readily suggest the iconography of a modernist movement entirely composed of men. Yet for the core members of the group, a significant part of the experience of modern life was explored and articulated through the depiction of this traditionally non-male domain. Paintings of female subjects, especially within working or lower middle class settings, defined a particular kind of contemporary urban existence which by virtue of its everyday normality was perceived to be authentically ‘real’. This sustained focus on the realm of the domestic bucked the dominant gendering of space that underpinned Victorian and Edwardian society; the notion of the masculine sphere of public life, as opposed to the private feminine world of home and family.1

However, the ironic paradox embedded within Camden Town paintings is that, although women and the domestic sphere feature prominently as subject matter, female artists were expressly excluded from membership of the group. This essay introduces the social and historical context for the theme of domesticity and the domestic interior, and contrasts images by the Camden Town circle with those of two contemporary women artists, Ethel Sands and Vanessa Bell.

Women in Edwardian England

The Camden Town Group’s interest in the domestic interior reflects a wider awareness of the condition of women during the Edwardian period. The early twentieth century witnessed the growing visibility of women as an active social force, and factors such as a drop in the national birth rate, the reform of the marriage laws and improvements in the education system led to general improvements in health and status. The most obvious example of women’s greater profile in public life is the campaign for women’s suffrage, but there was also escalating female representation within the workplace. The census of 1901, for example, reveals that seventy-seven per cent of women aged fifteen to thirty-four did some sort of paid work. Most of these were in domestic service but many were secretaries, typists, teachers and nurses.2 By 1903 women had their own school of medicine, the London (Royal Free Hospital) School of Medicine, and their own newspaper, the Daily Mirror, which was initially run by an all-female staff.3 There were also instances of women breaking into traditionally male professions, such as veterinary science, architecture and accountancy, although these were still rare, isolated exceptions, and only men could practise law.4

Women also became the increased focus of attention within contemporary culture. There was a general fascination with modern life as experienced by ‘the fairer sex’, and writers concerned with portraying the state of Edwardian England wrote realist novels about female characters from across the social spectrum. The eponymous heroine of Somerset Maugham’s Liza of Lambeth (1897), for example, is a factory worker in London, while Arnold Bennett’s Anna of the Five Towns (1902) concerns a middle class girl from the Potteries, Staffordshire. J.M. Barrie’s play What Every Woman Knows (1908), meanwhile, is a humorous but incisive commentary on the role played by women in upper middle class society, and the novel Ann Veronica (1909) by H.G. Wells focuses on the feminist struggle to achieve political, social and personal emancipation. The most popular novel of 1914 was Chance by Joseph Conrad. The author himself said that it was ‘All of it about a girl and with a steady run of references to women in general. It ought to go down.’5 Although it was not the figure of the ‘New Woman’ that featured in paintings by the Camden Town Group, this type of socially orientated literature certainly found a parallel within their art, particularly through their images of working or lower middle class women pictured within the cluttered, commonplace spaces of daily domestic life.

A marked shift in women’s roles occurred during the Edwardian era, particularly within the domestic sphere. For the art critic John Ruskin in 1865, the man was the ‘doer, the creator, the discoverer, the defender’, while the woman’s intellect was for ‘sweet ordering, arrangement and decision’.6 Yet although the house was traditionally seen as a feminine space, the business of furnishing it was often understood as a male preserve.7 Women had no property rights and limited earning power, and therefore historically it had been the man of the house who had economic control over the domestic interior.8 By the end of the nineteenth century, however, this situation had changed. The growth in suburban living meant that husbands commuted to their workplace leaving their wives in charge of household affairs and a growing number of women became involved in decorating their homes.9 Women were increasingly perceived to be the principal consumers and arbiters of domestic design and a wealth of popular literature offering advice on home furnishing was aimed at a predominantly female audience. For some, the domestic interior emerged as a symbol of feminist independence and a link was forged between creative expression and personal identity.10

The Camden Town Group: a ‘one sex club’

Just as they were trying to break into other walks of life, so women were struggling to gain recognition within the professional art world. According to the census for 1901 there were 3,699 women with the occupation of artist, rising to 4,202 in 1911 (as opposed to 10,250 men in 1901 and 7,417 in 1911).11 The intake of female students in artistic education was much higher during the Edwardian than the Victorian era, particularly in establishments such as the Slade and the Westminster School of Art, yet they still had to overcome the patriarchal stereotype of the mediocre ‘amateur’ lady, dabbling before marriage.12

Despite the fact that the Fitzroy Street Group had included women, the Camden Town Group, as noted earlier, firmly declared itself a ‘male club’ where ‘women are not eligible’.13 According to Charles Ginner this ban was devised by Gilman and Sickert to avoid the inclusion of wives or lady friends who ‘might not quite come up to the standard aimed at by the group’.14 Available correspondence also suggests that they had specific individuals in mind. In response to a request from Esther Pissarro that her friend Diana White be elected, James Bolivar Manson explained that the policy had ‘no malicious intention’ but arose from the ‘disinclination of the group to include Miss S[ands] & Miss H[udson] of Fitzroy Street in the list of members’.15 This was probably a politic spin on the truth since Sickert appears to have disliked Esther Pissarro.16 Furthermore, although Lucien supported his wife’s friend’s cause, he himself was later to accuse Sickert of swamping Fitzroy Street with a ‘sea of amateurs and pupils’, most of whom were undoubtedly female students from Sickert’s private art school, such as Renée Finch and Jean McIntyre.17 Whatever the truth, the single-sex ruling excluded a number of talented women whose work shared stylistic and thematic preoccupations with the core members of the Camden Town Group, particularly Sylvia Gosse, Stanislawa de Karlowska (Mrs Robert Bevan), Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands. It also denied an exhibiting platform to artists from the wider modern London milieu, such as Vanessa Bell, who was overlooked, whereas her Bloomsbury counterpart, Duncan Grant, was invited to join the group.18

An overriding reason for the single-sex stricture appears to have been the persistent antipathy towards the notion of the female ‘amateur’. Fundamental to the Camden Town ethos was the desire to sell work within an open marketplace, and there seems to have been an underlying prejudice against artists who were not under any necessity to make a living from their work or who did not fully commit their time to the progress of their art. The mark of the professional artist, therefore, was the sale of work. For many female artists, however, the opportunity to pursue artistic studies in the first place depended upon economic stability and social position. The attendant privileges of background and class often reduced their need to earn money but frequently engendered a host of other duties and distractions which competed for creative time and energies. Sickert was constantly berating Sands and Hudson for neglecting their artistic development in favour of social and domestic activities, and on one occasion threatened to oust them from Fitzroy Street. He chided Hudson:

I am a little cross with you both. I thought you were both going to work daily & produce & improve. Otherwise what do you get out of helping to pay for our studio? I meant you to improve by leaps & bounds! What in heaven’s name do you do? ... Of course women are – there is no doubt – we all know what they are je lache le mot – ‘aesthetes’. Pour moi c’est le plus gros mot que je connaisse. [I release the word – ‘aesthetes’. For me it is the coarsest word I know.]19

By ‘aesthetes’ Sickert implied those excessively concerned with stylish furnishings and decorations, as opposed to the ‘real’ and ‘natural’ beauty found in a ‘common little lodging room’.20 ‘Taste’, he maintained, was ‘the death of a painter’ and he believed that true poetry in art arose from the ‘interpretation of ready-made life’, achieved through dispassionate observation of the subject, unencumbered by emotion or personal preference.21 While creativity flourished in ‘the scullery, or on the dunghill’, it faded ‘at a breath from the drawing-room’.22 Sickert described the tendency of Sands and Hudson to produce paintings of their own interiors, still lifes and flower paintings as ‘something amateurish’, adding ‘Your own tastes in dress & your personalities should be banished as much as possible from your oeuvre. “Parler de soi c’est ce qu’il y a de moins fort” Flaubert says [To speak of oneself is of the least significance] ... There is a constant snare in painting what is part of your life.’23 His famous doctrine that ‘The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts’ and that serious art should ‘avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen’ disparaged paintings of genteel, feminine subjects as lightweight and superficial.24

The kitchen versus the drawing room

Although Camden Town artists frequently represented the domestic interior, many of their paintings follow Sickert’s principles, eschewing upper class refinement in favour of the lower class and workaday. Their images depict female subjects as urban ‘types’, generic characters who could be socially codified through the specific details of their clothing and surroundings.25 Furthermore, these glimpses into the domestic arena are presented from the viewpoint of a detached male observer, characterising a world to which he assuredly does not belong.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Shopping List 1912

Oil paint on canvas

615 x 510 mm

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Shopping List 1912

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Flowered Hat or Someone Who Waits c.1907

Oil on canvas

508 x 406 mm

Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

The Flowered Hat or Someone Who Waits c.1907

Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

In images such as Shopping List 1912 (fig.1), Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15 (private collection),26 or Tea in the Bedsitter 1916 (Huddersfield Art Gallery),27 Gilman, described as the ‘great painter of tea-pots’,28 created private, insular spaces inhabited by pensive women preoccupied by menial activities or so lost in reverie that they appear unaware of being viewed. Spencer Gore underlined the sense of separation in his painting, The Flowered Hat or Someone Who Waits c.1907 (fig.2), which juxtaposes a female sitter confined indoors (even though she has her hat on) with the bowler-hatted flâneur character in the street beyond. Sickert’s own figures in interiors, meanwhile, have been described as ‘anti-domestic’.29 Pictures such as Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846), Off to the Pub 1911 (Tate N05430, fig.3) or the Camden Town Murder series of 1907–9, reinforce middle class prejudices about working class existence, presenting dingy urban rooms as the stage-set for drama, dysfunction, drunkenness and violence.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Off to the Pub 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 695 x 595 x 45 mm

Tate N05430

Presented by Howard Bliss 1943

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Off to the Pub 1911

Tate N05430

© Tate

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

The Chintz Couch c.1910–11

Oil paint on board

support: 465 x 385 mm

Tate N03845

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Fig.4

Ethel Sands

The Chintz Couch c.1910–11

Tate N03845

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Contemporary female artists, however, portrayed domestic interiors from an entirely different perspective. In defiance of Sickert’s dictum to ‘avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen’, Sands resolutely drew inspiration from her own everyday environment: the comfortable living spaces of a wealthy and cultured Edwardian woman. A characteristic example, The Chintz Couch c.1910–11 (Tate N03845, fig.4), depicts a tastefully arranged room in her Belgravia townhouse. For Sands the home was not a place of introspection, confinement or angst, but somewhere she felt free and at ease. The care with which she decorated and then pictorially represented her home is evidence, not of repressive conformity, but of individual expression and a confident modern interest in the domestic sphere. An independent woman of considerable private means, she owned properties which reflected not only her material prosperity but also her flair for colour, beauty and texture. Her presence as the owner and occupier of these spaces is explicitly evident through the feminine fabrics and artfully arranged arum lilies.

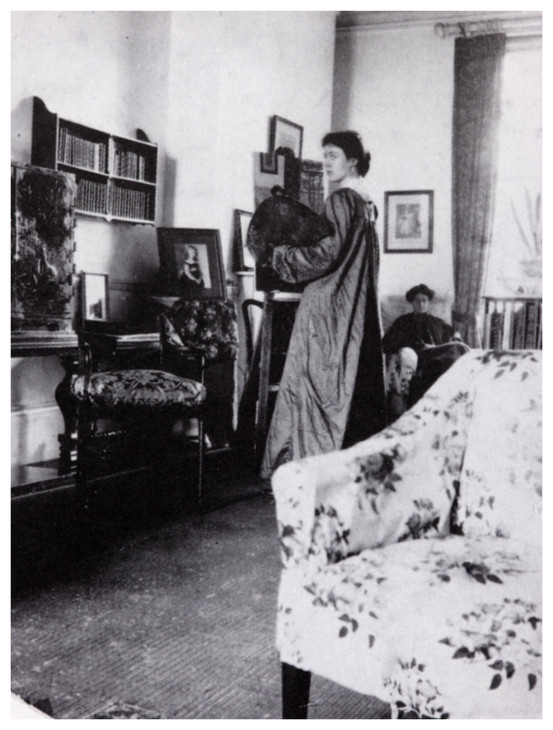

Vanessa Stephen Painting Lady Robert Cecil 1905

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

Tate Archive TGA 9020

Fig.5

Vanessa Stephen Painting Lady Robert Cecil 1905

Tate Archive TGA 9020

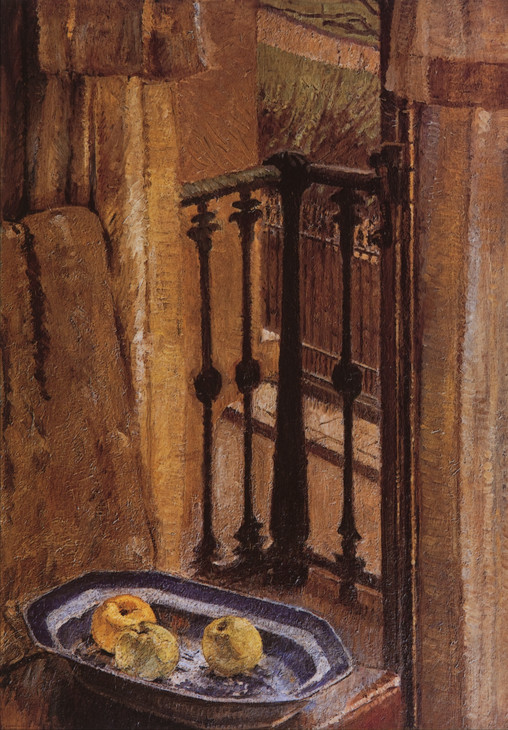

The domestic interior is therefore both the site and theme of female creativity. This is further evident within one of the few early surviving oil paintings by Bell, 46 Gordon Square c.1908–9 (fig.6), which shows a corner of her home with its furnishings and fruit bowl, and a glimpse of the ordered Bloomsbury square through the window beyond. The artist’s use of modern devices such as the stippled application of paint, strong compositional vertical and abruptly truncated view demonstrates that she saw domestic living as a viable subject for work of a modern character. It also reveals a stylistic and thematic connection at this time to the work of Fitzroy Street (and later Camden Town Group) artists such as Sickert’s Girl at a Window, Little Rachel 1907 (Tate T06447, fig.7) and Gore’s The Flowered Hat 1907 (fig.2).

Vanessa Bell 1879–1961

46 Gordon Square c.1908–9

Oil paint on canvas

736 x 507 mm

Private collection, on loan to the Charleston Trust

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Fig.6

Vanessa Bell

46 Gordon Square c.1908–9

Private collection, on loan to the Charleston Trust

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Girl at a Window, Little Rachel 1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 765 x 665 x 75 mm

Tate T06447

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax and allocated to the Tate Gallery 1991

© Tate

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

Girl at a Window, Little Rachel 1907

Tate T06447

© Tate

Rooms of their own

It was partly through their careful manipulation of the domestic interior that Sands and Bell asserted their right to be a part of cultured society. Both women were interested in interior design and in engendering surroundings which professed their artistic modernity. Sands invested much of her time perfecting decorative schemes at her London homes, her country home in Newington, near Oxford, and later with Nan Hudson in the aesthetic refurbishment of the seventeenth-century Château d’Auppegard near Dieppe.32 In addition to her careful personal selection of fixtures and fittings, she invited contemporary artists to create bespoke pieces, such as Boris Anrep’s murals and mosaics for her house in the Vale, Chelsea, and Sickert’s unfinished New Bedford mural decorations for the dining room there. In 1927 she and Hudson commissioned Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to decorate the walls of the loggia at Auppegard, while she herself completed some trompe l’oeil decorations for the bathroom and lavatory.

Bell, meanwhile, was a co-director and key contributor of designs to the Omega Workshops (1913–19), an enterprise initiated by Roger Fry for the production of household furnishings and clothes. Although the group was accused in an infamous open letter by former member Wyndham Lewis of being the ‘curtain and pincushion factory of Fitzroy Square’ that perpetuated the effeminacy of Victorian prettiness,33 its aim was to synthesise recent developments in French painting with the decorative arts. Among Bell’s Omega output were bold and colourful abstract designs for fabrics, hand-painted furniture and complete room schemes, as well as mural decorations for Charleston, her farmhouse in East Sussex.34

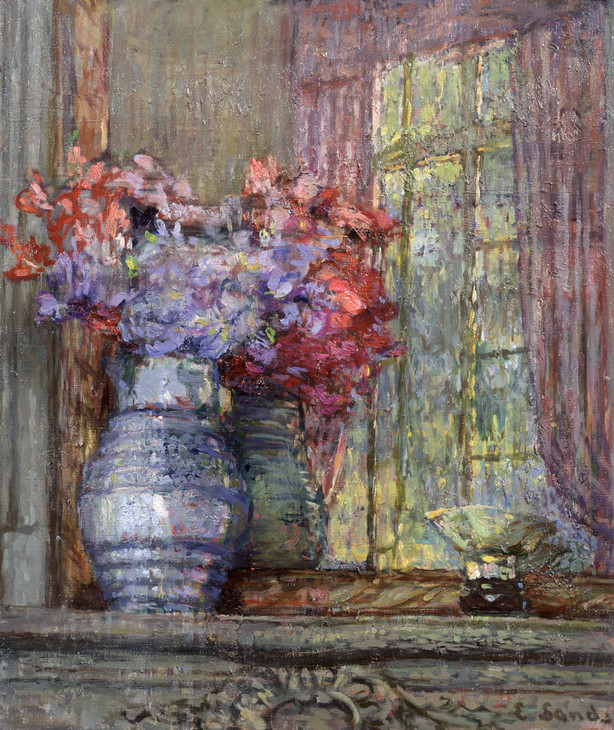

Although she is known to have disliked Sands’s preference for the ‘fatal prettiness’ of eighteenth-century style floral furnishings, their shared interest in interior decoration should be understood as mutual recognition of the importance of environment and the expression of personal identity, and a commitment to the values of modern living.35 They both created a domestic milieu which they felt represented their artistic objectives, while simultaneously nurturing their creative inspiration. A distillation of their individual styles can be best illustrated through two images, Bell’s Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914 (Tate T01133, fig.8), and Sands’s Flowers in a Jug ?1920s (Tate T07809, fig.9). While Sands’s naturalistic painting depicts the delicate elegance of an interior at Auppegard, the ornaments on Bell’s mantelpiece include some handmade paper flowers from the Omega Workshops, and the entire painting is an essay in abstract form and post-impressionist colour.

Vanessa Bell 1879–1961

Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914

Oil on canvas

support: 559 x 457 mm; frame: 614 x 512 x 49 mm

Tate T01133

Purchased 1969

© The estate of Vanessa Bell

Fig.8

Vanessa Bell

Still Life on Corner of a Mantelpiece 1914

Tate T01133

© The estate of Vanessa Bell

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

Flowers in a Jug ?1920s

Oil paint on canvas

support: 550 x 460 x 18 mm; frame: 678 x 588 x 45 mm

Tate T07809

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Fig.9

Ethel Sands

Flowers in a Jug ?1920s

Tate T07809

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Both Sands and Bell used their carefully constructed domestic environments as social contexts where they could participate in intelligent discourse more usually conducted in the male-dominated public sphere. Bell hosted the weekly ‘Friday Club’ gatherings of writers, artists and other intellectuals, which would eventually coalesce into the Bloomsbury Group. Sands’s homes in Oxford and London, meanwhile, were the setting for some of the most interesting and artistic gatherings of the period, the Edwardian equivalent of the French salon, including among her regular guests Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry and Walter Sickert. Paintings of interiors by these two women, therefore, also reflect the domestic interior as a microcosm of a wider social and cultural experience. Rather than the self-contained sequestered environment frequently portrayed by men, the domestic domicile is the location for conversation and the exchange of ideas. Sands’s painting, Tea with Sickert c.1911–12 (Tate T07808, fig.10), for example, represents an instance of cross-gender social interaction. The suited figure of Sickert is seated opposite an unknown female (probably Sands’s companion, Nan Hudson) with the empty chair in between them denoting the presence of the artist herself. Despite the self-assured, somewhat proprietary manner of Sickert’s pose, he is thoroughly assimilated within the feminine trappings of chintz furnishings and the afternoon tea tray, and although his body language suggests that he may be dominating the conversation, he is not dominating the pictorial space. He appears as part of Sands’s world.

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

Tea with Sickert c.1911–12

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 510 x 20 mm

Tate T07808

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Fig.10

Ethel Sands

Tea with Sickert c.1911–12

Tate T07808

© The estate of Ethel Sands

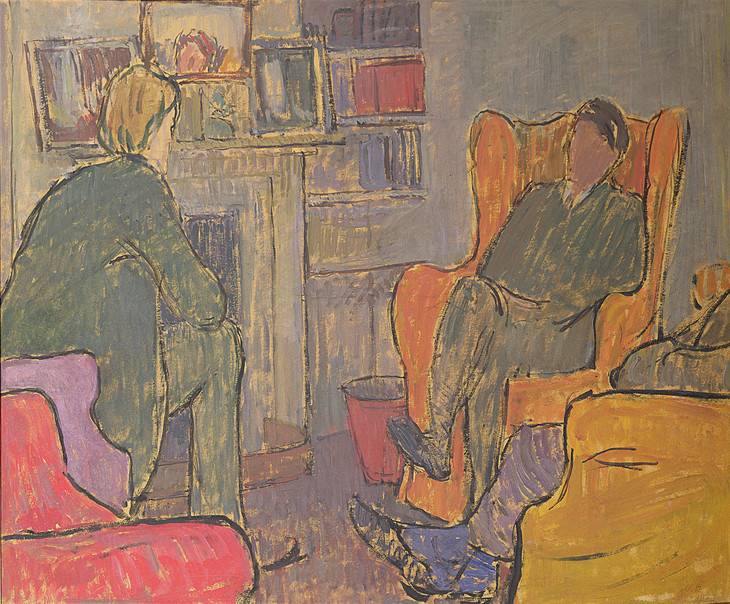

Vanessa Bell 1879–1961

Conversation Piece at Asheham 1912

Oil paint on board

585 x 763 mm

University of Hull Art Collection

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © University of Hull Art Collection, Humberside, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.11

Vanessa Bell

Conversation Piece at Asheham 1912

University of Hull Art Collection

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © University of Hull Art Collection, Humberside, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Vanessa Bell also painted an ‘at home’ meeting of minds in her 1912 picture, Conversation Piece at Asheham (fig.11). The setting is Asheham House, near Lewes in Sussex, a rural holiday home rented by Leonard and Virginia Woolf from 1911. Sitting at ease around the fire in vibrantly coloured high-backed winged armchairs are three figures. Despite their featureless visages, the trio have been identified as Vanessa’s husband, Clive Bell (wearing blue socks), Leonard Woolf in the centre, and the lanky figure on the left is Vanessa’s brother, Adrian Stephen. He leans forward as though engaged in intense and animated discussion. Although the three conversationalists are all men, the empty armchair on the left suggests that a fourth member has momentarily stepped away. The intimate atmosphere and domestic informality creates a sense that the artist (and by association the viewer) is looking in without being excluded, and is therefore an equal participant in the proceedings.

Vanessa Bell 1879–1961

Conversation 1913–16

Oil paint on canvas

866 x 810 mm

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Fig.12

Vanessa Bell

Conversation 1913–16

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Conclusion

According to Virginia Woolf, ‘Men and women see the same world but through different eyes’.36 In a famous essay of 1929 she argued that a woman’s intellectual and imaginative freedom depended upon a degree of financial independence and ‘a room of one’s own’, and paintings by Sands and Bell can be seen as visual expressions of a similar idea.37 Throughout their lives both women continued to paint pictures which centred on the domestic sphere, including interiors, still lifes and portraits of close friends and family. Unlike contemporary representations by the male Camden Town artists, they depicted spaces which are highly personal and individualistic, and which locate or imply a woman’s presence as an extension of the self. Furthermore, through their own forays into interior design they utilised domestic taste and décor as an expression of artistic modernity. Although there were distinct differences in their individual approaches and styles, both women established the domestic interior as a site of independence and creative expression.

Notes

There is an established literature exploring the theory of gendered space in relation to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art; see, for example: Griselda Pollock, ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, London 1988; Clarissa Campbell-Orr (ed.), Women in the Victorian Art World, Manchester and New York 1995; and Christopher Reed (ed.), Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, London 1996.

The 1901 census shows that there were six female architects, three vets and two accountants. Quoted in Hattersley 2004, p.80.

John Ruskin, ‘Sesame and Lilies’, 1865, part II, in E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin, London 1903–12, vol.18, pp.121–2.

There is considerable literature associated with this subject; for example: Judy Attfield and Pat Kirkham (eds.), View from the Interior: Feminism, Women and Design, London 1989; Thad Logan, The Victorian Parlour: A Cultural Study, Cambridge 2001; John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England, New Haven and London 1999; Joanna Banham, Sally Macdonald and Julia Porter, Victorian Interior Design, London 1991; and the literature and research activities of the Centre for the Study of the Domestic Interior, http://csdi.rca.ac.uk/ and http://csdi.rca.ac.uk/didb/index.php . The change has also been discussed by Lisa Tiersten with reference to Paris, ‘The Chic Interior and the Feminine Modern: Home Decorating as High Art in the Turn-of-the-Century Paris’, in Reed (ed.) 1996 and Cohen 2006.

Quoted in Lisa Tickner, ‘Men’s Work? Masculinity and Modernism’, in Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxley (eds.), Visual Cultures: Images and Interpretations, New England 1994, pp.60 and 78 n.70.

Sylvia Pankhurst studied on a scholarship at the Royal College of Art in 1904 but was convinced that the Principal discriminated against women in the distribution of internal awards. See Hattersley 2004, p.208. For a discussion of women’s art education during the period, see ‘Training and Professionalism, 19th and 20th Centuries’, in Delia Glaze (ed.), Dictionary of Women Artists, vol.1, London 1997, pp.80–8.

See Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson, undated [?1914], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.10, where he describes Esther as ‘stupid & disagreeable’.

See the list of artists who applied for membership of the London Group, many of whom were students of Sickert’s, in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, fig.1, [p.14].

Later, however, Sickert does seem to have tentatively approached Bell with the idea of amalgamating the Fitzroy Street and Grafton groups, in which case, as he wrote to Nan Hudson ‘any rules about the sexes ipso facto’ would henceforth lapse, gender ‘distinctions having become, not only insidious but impossible’. Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson, undated [?1913], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.152.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.185.

See Nicola Moorby, ‘Portrait / Figure / Type’, in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, p.97.

See Louis Fergusson, ‘Souvenir of Camden Town. A Commemorative Exhibition’, Studio, February 1930, p.31.

Christopher Reed, Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture and Domesticity, New Haven and London 2004, p.148.

For further discussion, see the biographies and catalogue entries for Sands and Hudson in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/ethel-sands-r1105348 and http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/nan-anna-hope-hudson-r1105358 .

See ‘On to Omega: The Workshop’s Origins and Objects’, in Reed 2004, pp.109–63, and ‘The Omega Workshops’, in Shone 1993, pp.90–117.

Bell questioned the ability of Sands and Hudson to produce designs for the Omega Workshops, writing to Roger Fry ‘Can’t we paint stuff’s, etc., which won’t be gay and pretty?’. Vanessa Bell, letter to Roger Fry, 21 July 1912, in Regina Marler (ed.), Selected Letters of Vanessa Bell, New York 1993, pp.120–1.

Nicola Moorby is a Cataloguer at Tate Britain.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www