Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group

Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

The artists of the Camden Town Group relished the diversity of entertainment available in London before the First World War. Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke survey their approach to leisure, both as painters and as participants, exploring their fascination with London’s cafés, bars, restaurants, theatres, cinemas and music halls.

The huge variety of public leisure interiors – cafés, music halls and clubs among them – depicted by artists linked to the Camden Town Group reveal their enthusiasm for and direct engagement with the new entertainment and refreshment spaces of modern urban life.1 Inevitably many of the interiors portrayed were located in England’s capital city. The leisure districts of early twentieth-century central London were safer, better lit and more easily accessible than they had been in the 1890s, and the expansion of the Underground network and the rise in motorised travel allowed many more people the opportunity to enjoy a daytrip to the city.

Writing in 1902, the journalist George Sims imagined the ideal metropolitan excursion in an article entitled ‘A Country Cousin’s Day in Town’.2 Beginning with a trip to Madame Tussaud’s, a ride to Tower Hill on the Metropolitan Railway, and a refreshment stop at Pimm’s luncheon counter, the morning would end with a stroll around the Royal Aquarium, a visit to St James’s Hall in Piccadilly and to the nearby Egyptian Hall. The evening would commence with dinner in the artists’ room at Pagani’s, a visit to the ‘poetic and beautifully draped’ ballet at the Alhambra Theatre, a ‘long glass of lager’ in the continental style at the cosmopolitan Hotel de L’Europe with its Parisian inspired décor, and a visit to the latest moving picture show at the Palace Theatre. After catching the end of the ballet at the Empire, the evening would draw to a close with a peep into the ‘luxurious Criterion bar and American café’, a glance at the seafood display in the window of Scott’s, and a leisurely nightcap at the Café Royal ‘seated comfortably on a luxurious lounge’.3

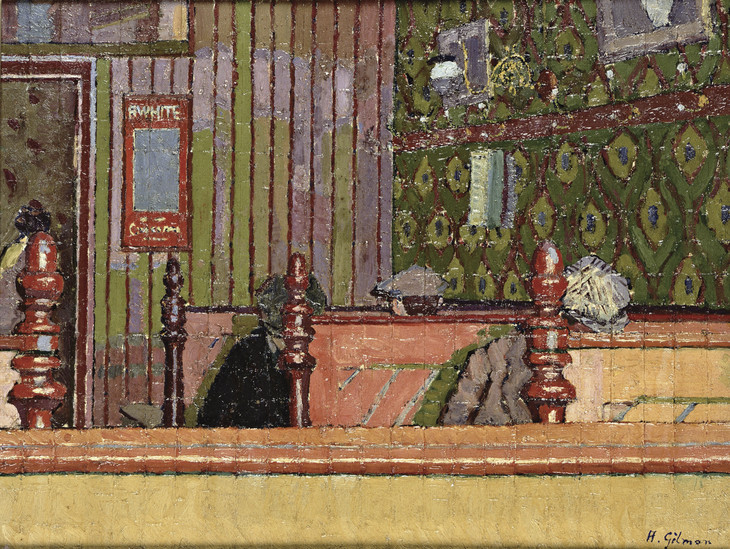

Sims’s text records London’s leisure scene on the verge of change as popular Victorian amusements gave way to newly emerging entertainments, including cinema and variety theatre. In the area of public dining, different types and classes of refreshment place opened to meet the recreational and practical requirements of particular audiences. Chains such as Pearce and Plenty, for instance, catered to the early morning and lunchtime needs of the working classes, supplying around forty thousand meals a day at an average cost of twopence.4 Their relatively sparse and functional interiors, as illustrated in Gilman’s An Eating House c.1913–14 (fig.1), can be contrasted with middle class dining spaces, which afforded greater privacy to customers in emulation of the domestic model. In commercial districts the habit of counter dining, often standing, was favoured by clerks and businessmen with little time for eating.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 337 x 394 mm; frame: 440 x 496 x 72 mm

Tate N06238

Presented by the artist's family 1954

© Tate

Fig.2

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Fried Fish Shop c.1907

Tate N06238

© Tate

For those who preferred to eat at home the possibilities also expanded. The fried fish and chip shop, for example, had come into being in the 1860s. It was a convergence of back-street fried fish shops, whose owners cooked in batter pieces of fish rejected by costermongers, and outlets that sold baked potatoes, which had become increasingly popular snacks at fairs and wakes. The 1907 painting of a fish and chip shop by Stanislawa de Karlowska (Tate N06238 fig.2) captures a moment when the consumption of this meal was still an exclusively working class activity.

Artists’ cafés

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.3

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

William Orpen 1878–1931

The Café Royal 1912

Oil paint on canvas

1035 x 1035 mm

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.4

William Orpen

The Café Royal 1912

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Adrian Allinson 1890–1959

The Café Royal 1915–16

Oil paint on canvas

102 x 127 cm

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

Fig.5

Adrian Allinson

The Café Royal 1915–16

Private collection

© Estate of Adrian Allinson

The Café also provided one of the spaces in which the future creation of the Camden Town Group was discussed by regulars such as Walter Sickert, Robert Bevan, J.B. Manson, Spencer Gore and Ginner. The latter was by no means alone in wishing to celebrate this particular space in paint; in May–June 1912 Orpen’s The Café Royal (fig.4) was exhibited at the New English Art Club in which, like Ginner, the focus was on the details of the interior and the interplay of reflection and light from the mirrored walls. By the time Ginner’s The Café Royal was first exhibited, the Domino Room was also increasingly frequented by a younger generation of artists, then still students at the Slade School of Fine Art, including Adrian Allinson (fig.5), John Currie, Mark Gertler, C.R.W. Nevinson and Edward Wadsworth.7

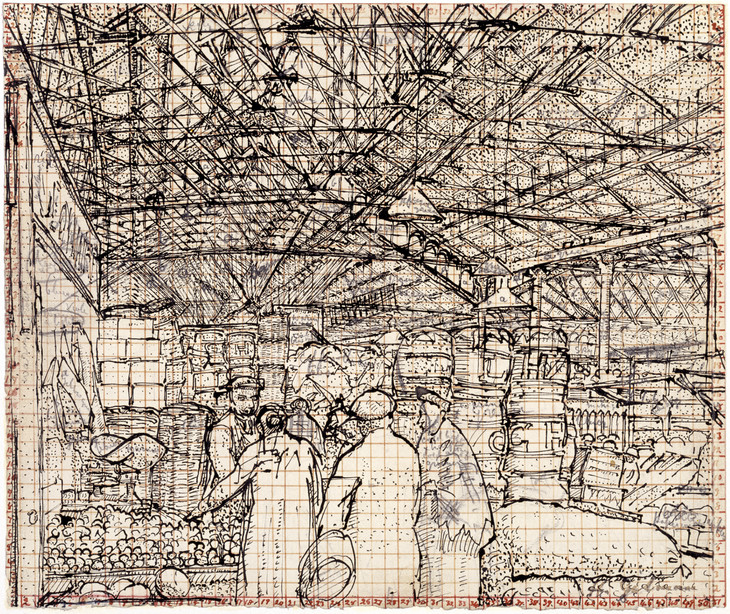

As the Camden Town Group was about to be launched in 1911, younger and more stylistically adventurous Slade art students were keen to make their mark in the art world. In addition to the Café Royal, they also sought to establish their own more informal haunts in which to socialise. Early in 1911 the ‘Slade Coster Gang’, comprising Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot (later that year elected the youngest member of the Camden Town Group), Allinson, Currie, Gertler, Nevinson, Stanley Spencer and Wadsworth, began to meet regularly at the Petit Savoyard, a small French café-restaurant at 33 Greek Street in Soho. The members of the ‘Gang’ took to dressing self-consciously as ‘coster toughs’, wearing flat caps, checked corduroy waistcoats and heavy black boots with brightly coloured silk scarves around their necks. Prior to adjourning to the Petit Savoyard for a hearty dinner, they enjoyed provoking punch-ups in and around Tottenham Court Road with genuine costers (who operated a number of fruit stalls on nearby Windmill Street), navvies digging up roads, and medical students from University College Hospital. Allinson, Nevinson and Wadsworth appear to have painted murals for the Petit Savoyard interior, now lost. Their enthusiasm for working class life was shared by members of the Camden Town Group, notably Harold Gilman, who sketched the Market Hall in Leeds on a trip to that city, made a study of working men in a café in The Eating House, and painted numerous interior studies of coster-girls, and his housekeeper, Mrs Mounter (figs.6, 1 and 7).

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Study for 'Leeds Market' c.1913

Ink and pencil on paper

support: 250 x 297 mm

Tate T00143

Purchased 1957

Fig.6

Harold Gilman

Study for 'Leeds Market' c.1913

Tate T00143

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 406 mm; frame: 808 x 605 x 93 mm

Tate N05317

Purchased 1942

Fig.7

Harold Gilman

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Tate N05317

In April 1914 the Crabtree Club opened on Greek Street to appeal to a similar clientele. Founder members included William Marchant (Director of the Goupil Gallery), Lord Howard de Walden and Augustus John. For a while, according to John, all was sweetness in the Club, ‘apart from the [presence of] crabs’,8 and it quickly attracted many of John’s artist friends including Gilman, Gore, Lamb and Sickert. Paul Nash, on the other hand, found it to be ‘A most disgusting place ... where only the very lowest city jews and the pinched harlots attend. A place of utter coarseness and unrelieved monotony.’9

Around the time of the London Group’s first exhibition, early in March 1914, a number of former members of the Camden Town Group had discovered a new eating place at which to dine, socialise and plot: the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel at 1 Percy Street, just off Tottenham Court Road. The proprietor of what was later hailed as ‘for 30 years ... a meeting, dining and wining place for London Bohemians’, was the enigmatic Rudolf Stulik.10 John later claimed to have led the way, literally stumbling upon the Tour Eiffel one evening early in 1914 in the company of an equally inebriated Nancy Cunard.11 Once it had been ‘discovered’, the Tour Eiffel soon attracted the patronage of other former members of the Camden Town Group: Wyndham Lewis (living a few doors away at 4 Percy Street);12 Sickert (who had a studio just up the road at 19 Fitzroy Street, and proved a great consumer of a Tour Eiffel house speciality – the Sole Dieppoise); Henry Lamb (who had a studio nearby at 8 Fitzroy Street); Gilman (who lived close by at 47 Maple Street); Bevan; Ginner; Manson; and Duncan Grant (who in 1914 had just taken a studio at 22 Fitzroy Street to be close to the Omega Workshops at 33 Fitzroy Square).13

William Roberts 1895–1980

The Diners 1919

Oil on canvas

support: 1524 x 832 mm; frame: 1590 x 905 x 59 mm

Tate T00230

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1959

© The estate of William Roberts

Fig.8

William Roberts

The Diners 1919

Tate T00230

© The estate of William Roberts

The Tour Eiffel remained a popular destination between the wars with Ginner, John, Lewis, Paul Nash, Sickert and Wadsworth as well as a whole new generation of writers, artists and would-be bohemians. Stulik, however, took to drink and the establishment went bankrupt in March 1938. Refurbished it reopened later in 1938 as the White Tower restaurant, by which time Lewis’s vorticist panels had disappeared, as had two of the three produced by Roberts.17

The Studio Club, at 11 Regent Street, a haunt for ‘non-doctrinaire’ painters and the ‘art-minded’, grew out of the activities of ex-Camden Town Group members Bevan, Gilman and Ginner who had formed the Cumberland Market Group in 1915.18 The group had its sole exhibition at the Goupil Gallery, Regent Street in April 1915, along with new members John Nash and Edward McKnight Kauffer. During the early autumn of 1916, Bevan, Gilman, Ginner, Nash and McKnight Kauffer, joined by ex-futurist Nevinson, held Saturday afternoon ‘At Homes’, between 3 and 6 pm, in the Grey Room of the Goupil Gallery.

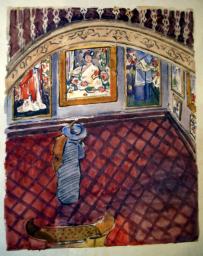

At Nevinson’s urging, these artists founded the Studio Club – just a few doors north of the Goupil Gallery and very convenient for the Café Royal on the other side of Regent Street – as a site where they could promote their art. The Club had its grand opening on Saturday 4 November 1916. Paintings by Bevan, Gilman, Ginner, Nash, Nevinson and McKnight Kauffer were exhibited in the Club’s main sitting room and the artists themselves were on hand to enrol new members.19 During 1917 Gilman, Ginner and Nevinson produced a series of murals in oil paint and gouache for the Club’s interior. A watercolour drawing depicting some of the murals by one Elfrieda Hughes was reproduced in the June 1918 issue of Colour Magazine. A bemused visitor to the Club in 1924 noted that the murals depicted an eclectic array of energetically leaping animals, including ‘black leopards, green devils and what I took to be a Futurist version of Tutankhamen rising from the tomb’.20 Unfortunately, these intriguing murals were lost in 1938 when the Club’s premises were demolished as the southern end of Regent Street underwent extensive redevelopment to make way for the creation of Air Street.

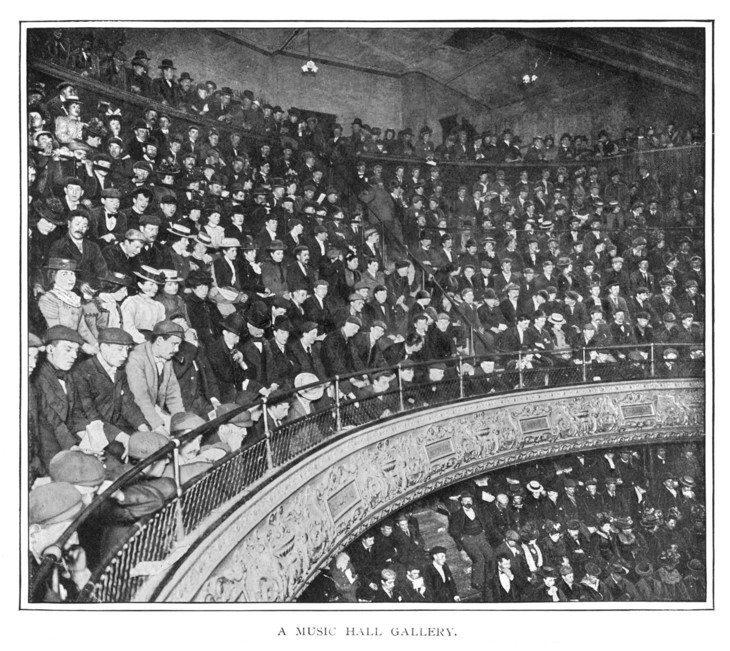

Popular entertainment

London’s larger West End theatres and modernised pubs and music halls catered to increasingly diverse audiences, and their interiors were indicative of a broad pattern of development that occurred as mass leisure environments evolved. The spatial organisation of these interiors, and the varying levels of ticket and refreshment prices that operated within them, served to differentiate the crowd, while the form and finish of their furnishings, styles of decoration and modes of service appealed to distinctive groups of clientele.

Gallery of a London Music Hall in 1900 1901 From George Sims, Living London, first published by Cassell

Photo courtesy Mary Evans Picture Library

Fig.9

Gallery of a London Music Hall in 1900 1901 From George Sims, Living London, first published by Cassell

Photo courtesy Mary Evans Picture Library

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Oil paint on canvas

support: 765 x 638 mm; frame: 915 x 787 x 69 mm

Tate T02039

Purchased 1976

© Tate

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Tate T02039

© Tate

The strong connection between the refreshment and the entertainment businesses can be seen most clearly in the music hall, which emerged out of the public house and, from the mid-nineteenth century, developed within independent, purpose-built theatres. During the 1880s and 1890s many of London’s early halls were rebuilt with enlarged capacities and improved public facilities. The same period saw the emergence of new halls in affluent outer suburbs and the gradual disappearance of minor public house halls, with their basic platform stages and communal dining tables. A subject favoured by Sickert and Gore, the music hall became the first mass entertainment industry and reached the height of its popularity in the Edwardian period (fig.9). Sickert first became interested in the subject in the mid-1880s, just as the older halls were disappearing. Many of his early works, such as Minnie Cunningham of 1892 (Tate T02039, fig.10), depict the performers. However, as the art historian Wendy Baron has noted, from the mid-1890s Sickert turned his attention to the audience (fig.11).21 The timing of this shift in perspective from performer (stage) to spectator (auditorium) is significant. In the 1890s a variety of cultural critics began to propose that commercialisation was endangering the status of music hall as an authentic cultural form.22

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.11

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 730 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.12

Walter Richard Sickert

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

At the same time many of the older, well-established halls that Sickert favoured began to be modernised, increasing their appeal to better class customers and contributing to the music hall’s expansion beyond its working class roots.23 By the beginning of the twentieth century, music hall had become a respectable and popular entertainment: crowds were orderly and more socially diverse, programmes were designed to have wider appeal, and the comfort of theatres was greatly improved. Topicality, an important element of music hall and a reflection of its close relationship with street culture, became a critical component of the sanitised variety performances that evolved in the improved halls and, as Andrew Horrall has indicated in his 2001 study, artists became adept at incorporating the latest public crazes into their repertoires.24 London’s halls and variety theatres fuelled and fulfilled a desire for novelty among an expanding urban mass market and provided a natural platform for the emerging medium of film.25 Moving images were incorporated into the programmes of several West End theatres in the 1890s, including the Empire, Palace and Alhambra, and were soon added to those of less celebrated halls, such as the Middlesex in Drury Lane, as Sickert depicted in his Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906 (fig.12).

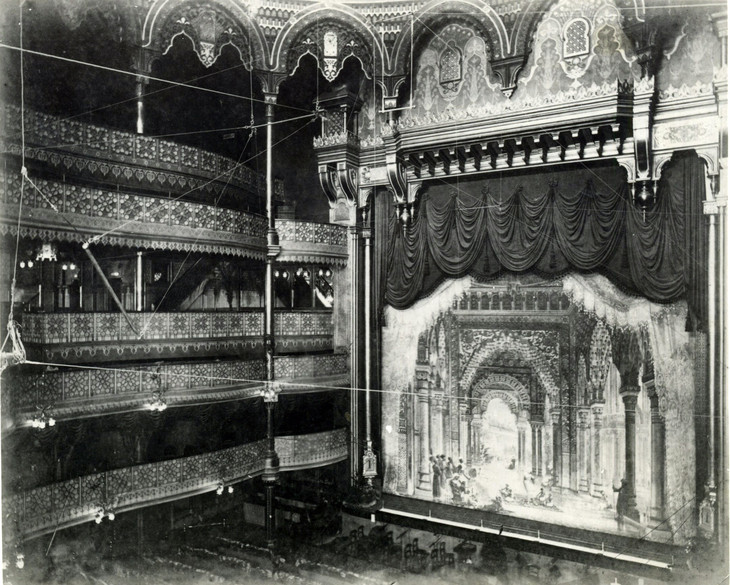

The ephemerality of London’s late Victorian and Edwardian music hall interiors mirrored the dynamic and mutable form of the music hall genre. Between major building works, theatres were regularly refitted and redecorated. For example, the Alhambra in Leicester Square was extensively altered in the thirty years before the First World War (fig.13). In 1892 the theatre’s ‘Alhambresque’ style of decoration was replaced with a lighter scheme in cream, white and gold.26 Structural elements of the building that had previously been on show were concealed behind elaborate plasterwork and the ceiling was decorated in blue with gold stars to resemble the sky. The fantastical atmosphere was enhanced by the introduction of over 120 new electric lamps and electroliers, which, finished in silver and gold ormolu, illuminated the mirrored Grand Circle and stalls, creating a glittering and fashionably modern social setting that was characteristic of many of London’s halls and variety theatres of the period.

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

Photographic print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.13

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

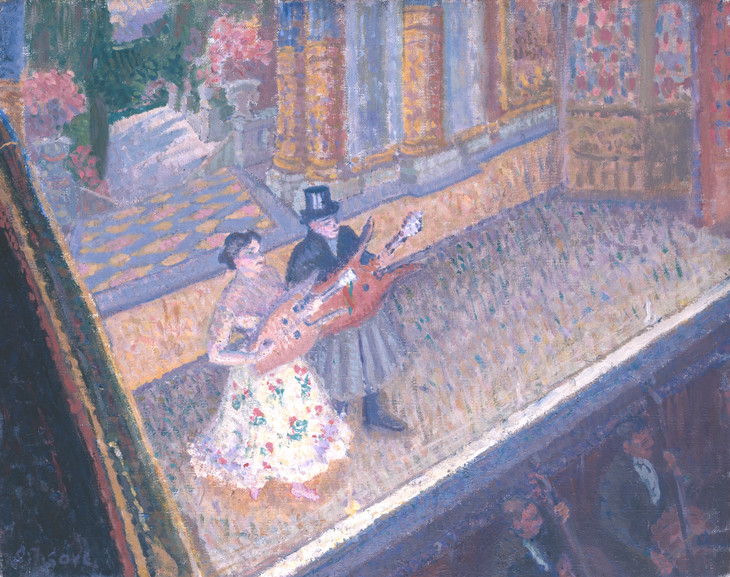

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Ballet Scene c.1903–6

Graphite and watercolour on paper

support: 375 x 280 mm

Tate N06016

Presented by Albert Rutherston 1951

Fig.14

Spencer Gore

Ballet Scene c.1903–6

Tate N06016

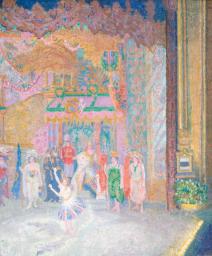

The Alhambra was known particularly for its mixed programme of ballet and music hall. Until around 1910 dance had a relatively low cultural status in England and classical ballet was only performed within music hall and pantomime productions; members of the corps de ballet, such as those depicted in Gore’s Ballet Scene of c.1903–6 (Tate N06016, fig.14), were usually working class girls with limited technical training.27 The painting, although most obviously related to other representations of theatrical entertainment, can also be considered within a genre of images of female working class labour that includes Albert Rutherston’s Laundry Girls of 1906 (Tate N04996), in which two girls are depicted marking washed linen items before returning them to their owners.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki 1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 406 x 508 mm; frame: 608 x 710 x 52 mm

Tate N05859

Purchased 1948

Fig.15

Spencer Gore

Inez and Taki 1910

Tate N05859

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.16

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Ballet Scene offers an impressionist view of the massed dancers, but other paintings by Gore from this period, such as Inez and Taki (Tate N05859, fig.15) and Rule Britannia (Tate T06521, fig.16) of 1910, both of which depict Alhambra productions, draw attention to details of costume, staging and performance. In Inez and Taki the darkness of the theatre box is contrasted with the partially illuminated orchestra pit, colourful clothes of the two performers, and brightly painted scenery to their rear. A similarly intense lighting effect can be seen in Gore’s A Singer at the Bedford Music Hall of 1912 (Tate T02260, fig.17). Modern variety theatres, unlike the pub music halls that were their predecessors, adopted the practice of darkening the auditorium for performances, heightening the visual effect of the elaborate production designs that became possible on their larger and more technically advanced stages.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

A Singer at the Bedford Music Hall 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 533 x 432 mm

Tate T02260

Presented by Mr and Mrs Robert Lewin through the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1978

Fig.17

Spencer Gore

A Singer at the Bedford Music Hall 1912

Tate T02260

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Oil paint on canvas

support: 914 x 356 mm; frame: 1105 x 545 x 62 mm

Tate N06174

Bequeathed by Sir Edward Marsh through the Contemporary Art Society 1953

© Tate

Fig.18

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Bedford c.1914–15

Tate N06174

© Tate

In The New Bedford of c.1914–15 (Tate N06174, fig.18), which depicts the Bedford Palace of Varieties in Camden High Street, Sickert represents a music hall audience in a modernised theatrical setting. Painted from extensive preparatory sketches, it was intended as part of a decorative scheme for his friend Ethel Sands’s Chelsea dining room.28 The verticality of the composition draws the viewer’s eye between the privileged space of the private box and the crowded stalls below, and in keeping with its intended function and location, reflects an interest in both the decorative qualities and social dynamics of the interior.

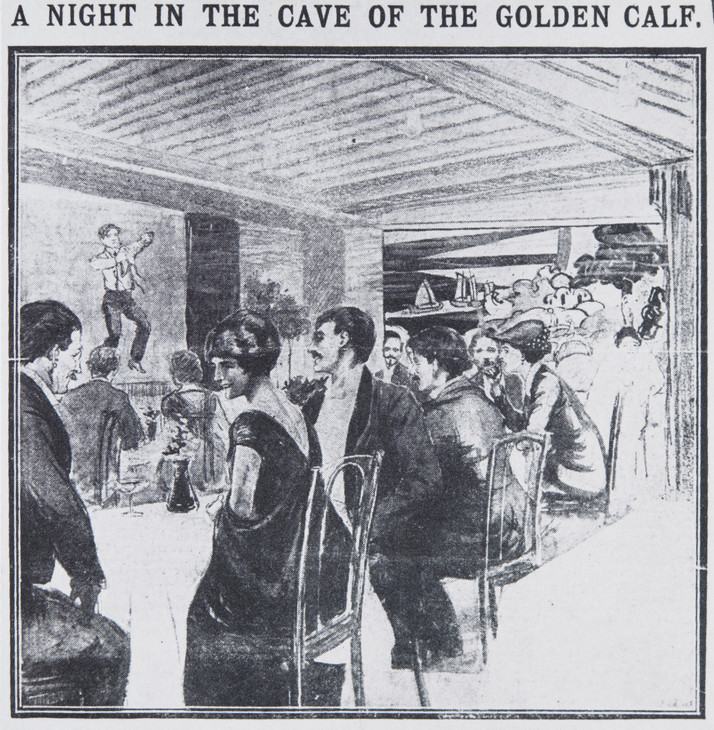

The Cave of the Golden Calf

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf' 1912

Oil paint and graphite on paper mounted on card

support: 305 x 605 mm

Tate T00446

Purchased 1961

Fig.19

Spencer Gore

Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf' 1912

Tate T00446

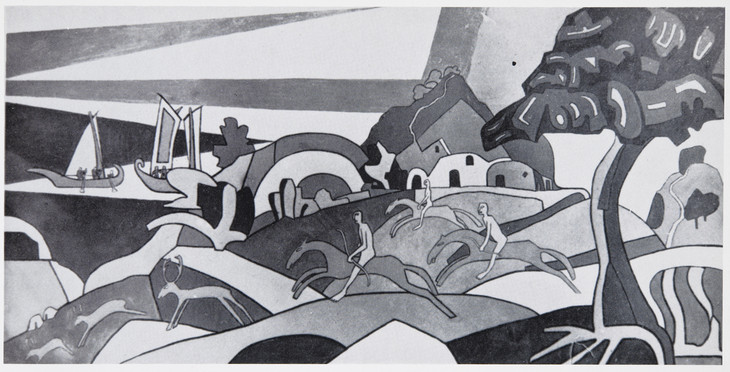

Gore was among a number of artists commissioned in 1912 by the manager, Frida Strindberg, to decorate the club’s interior. Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill provided sculpture (Gill carved a suitably gilded ‘golden calf’) while Gore, Ginner, Stanley Spencer (then still a young student at the Slade) and future vorticists Wyndham Lewis and Cuthbert Hamilton supplied mural designs. Gore produced a mural depicting a deer hunt while Ginner portrayed a tiger hunt (figs.20 and 21).31 These may well have been among those noted by the Times in June 1912 as ‘representing we should not care to say what precise stage beyond Impressionism – they would easily, however, turn into appalling goblins after a little too much supper in the cave’.32 Part of Gore’s mural appears in the background of a drawing titled ‘A Night in the Cave of the Golden Calf’ published in the Daily Mirror on 4 July 1912 (fig.22).33

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Deer-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912

Distemper on canvas

Dimensions unknown

Whereabouts unknown

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.20

Spencer Gore

Deer-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912

Whereabouts unknown

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Tiger-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912 Central panel of triptych

Distemper on canvas

Approximately 183 x 183 cm

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.21

Charles Ginner

Tiger-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912 Central panel of triptych

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Despite this array of talent the Cave failed to make money and, although it was relaunched in February 1914, it closed shortly after. Gore was still vainly attempting to extract payment from Strindberg for his mural, as well as for subsequent work on the club’s decoration, until his death in March of the same year.34

Conclusion

The diverse interiors of Edwardian London’s cafés, bars, restaurants and theatres shaped and expressed the tastes and aspirations of users, produced new subjectivities, reflected and consolidated gender and class identities, and regulated social use and commercial transactions. The members and associates of the Camden Town Group were acutely aware of contemporary tastes and tendencies within urban leisure and popular entertainment, and of the design of the interiors in which these were expressed. The artists were united by their fascination with working class lives and their own favoured leisure interiors, whether the ‘tawdry glamour’ of the early music halls or the special appeal and distinctiveness of the artistic cafés and clubs. Above all they were supremely sensitive to all that modernity had to offer them in the sphere of public leisure of which, as their paintings clearly demonstrate, they felt themselves to be an intrinsic component.

Notes

An important book on this topic is Peter Brooker, Bohemia in London: The Social Scene of Early Modernism, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2004.

George R. Sims, ‘A Country Cousin’s Day in Town’, Living London, vol.2, Cassell, London 1902, pp.344–50.

Michael J.K. Walsh, C.R.W. Nevinson: This Cult of Violence, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2002, pp.27–8.

Invitation card reproduced in Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early Twentieth Century England, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1985, fig.269, p.220.

O’Keeffe 2000, pp.519–20. The surviving Roberts panel, The Diners 1919, is now in Tate’s collection (Tate T00230).

See Barry J. Faulk, Music Hall and Modernity: The Late-Victorian Discovery of Popular Culture, Ohio University Press, Athens 2004.

Of the halls that Sickert represented almost all were rebuilt in the 1890s, including: Collins Music Hall in Islington Green (rebuilt 1897 by Drew, Bear, Perks & Co.); Queen’s Palace of Varieties in Poplar (rebuilt 1898 by Bertie Crewe); the Bedford in Camden High Street (rebuilt 1896–8 by Bertie Crewe); the Mogul, or Middlesex in Drury Lane (rebuilt 1891 and 1911 by Frank Matcham); and the Oxford Music Hall in Oxford Street (rebuilt 1893 by Wylson and Long). Only Gatti’s Charing Cross music hall and Botting’s at the Rose of Normandy public house in Marylebone High Street appear to have resisted substantial alteration.

See Andrew Horrall, Popular Culture in London, c.1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2001.

See Maurizio Cinquegrani, ‘Empire and the City: Early Films of London’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/maurizio-cinquegrani-empire-and-the-city-early-films-of-london-r1104356, accessed 21 August 2013.

‘The Alhambra Redecorated’, London, September 1892, unidentified press cutting, British Library, 85/1882.c.2.(124).

Amy Koritz, ‘Moving Violations: Dance in the London Music Hall, 1890–1910’, Theatre Journal, vol.42, no.4, December 1990, pp.419–20 and p.427.

Jonathan Black is Senior Research Fellow in History of Art, Dorich House Museum, Kingston University, London.

Fiona Fisher is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Modern Interiors Research Centre at Kingston University, London.

Penny Sparke is Pro Vice-Chancellor and the Director of the Modern Interiors Research Centre at Kingston University, London.

How to cite

Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke, ‘Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www