Introducing The Camden Town Group in Context

The Camden Town Group was a short-lived exhibiting society of artists, the name of which has since become synonymous with a distinctive type of painting and period in the history of British art before the First World War.

Named after the area of north London in which the artists Walter Sickert and Spencer Gore lived and painted, the Camden Town Group held just three exhibitions, all at the Carfax Gallery in fashionable St James’s, London, in 1911 and 1912. The group dissolved in 1913 but for a period it represented a determined effort by painters to explore new ways of representing the everyday realities of urban life in Edwardian Britain.

This project investigates the aims, history and achievements of this rather neglected exhibiting society. It charts how it evolved from Walter Sickert’s Fitzroy Street Group that held weekly gatherings from 1907 and how, in turn, it developed in 1913 into the larger and intentionally more diverse London Group, still active today. It also shows how, despite these changes in name (and, indeed, changes in membership), there were a number of shared characteristics for which ‘Camden Town’ has become a shorthand term. These do not include style – the members of the group valued originality of expression and accepted different approaches – but relate more to a shared ethos and ambition to respond to the social and cultural life of modern Britain, just as impressionist painters had painted scenes of ‘modern life’ in France a generation before.

Shunning ostentation and pretension, Camden Town artists produced small scale, modestly priced paintings showing the everyday surroundings and pursuits of typically lower middle and working class people. Social reportage was incidental to the painters’ attempts to make art based on truthful observation and to discover scenes of visual – and sometimes psychological – fascination within urban life. However, their choice of subject matter marked them as a distinctive force in London’s art world at the time and their works now offer tantalising insights into the sometimes jarring experiences of modern urban life in the period leading up to the First World War. Through these paintings we see, set amid reminders of London’s past, a world of motor vehicles, electric lighting and a modern Underground system, combined with unmistakeable signs of shabbiness and decline in areas like Camden Town.

Notwithstanding the rootedness of their paintings in the fabric of Edwardian culture, or perhaps because of it, the Camden Town Group experienced a degree of critical neglect for many years. Later scholars tended to pay more attention to the group’s more stylistically innovative contemporaries – those painters associated with Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury group, or the emerging vorticist group centred around controversy-courting Wyndham Lewis. The fervently expressed art politics and widely reported clashes between these two circles, who represented essentially contrasting positions in relation to European modernism, tended to dominate earlier accounts of this period in British art. The Bloomsbury painters, including Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, were perceived as expressing a more decorative, pleasurable and ‘life-affirming’ aesthetic, one associated with Cézanne, Gauguin and Matisse, and the vorticist painters and sculptors, including C.R.W. Nevinson, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein, as engaged with a more apparently ‘virile’, radical and aggressive aesthetic, associated in the first instance with the Italian futurists whose works had been shown in the Sackville Gallery in 1912.

Much attention has been devoted to the impact of Roger Fry’s two exhibitions, Manet and the Post-Impressionists of 1910–11 and the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition staged in late 1912. The shock value of these impressively large scale displays of European modernism was widely debated at the time and many, including painters from the once overtly francophile, impressionist-oriented New English Art Club (established in 1886) found works they contained – by van Gogh and Cézanne in particular – to be excessively crude and unnaturalistic. They were also unimpressed by Roger Fry’s and his associate Clive Bell’s insistence on the significance of these painters’ expressive distortions and simplifications of form.

This over-emphasis on Bloomsbury and on the vorticists has considerably over-shadowed the fact that other young painters in Britain – including Camden Town Group members Spencer Gore, Robert Bevan, Charles Ginner and Harold Gilman – were already very familiar with works by those Fry conveniently termed the ‘Post-Impressionists’, either from their own visits to France or to smaller exhibitions at home, including the Modern French Art show in Brighton in 1910 and the Exhibition of Pictures by Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin at London’s Stafford Gallery in 1911. Walter Sickert, with his sophisticated awareness of and connections to European painters, reviewed the first of these exhibitions in The Fortnightly Review in January 1911. He was amused by ‘the rumpus’ created by the ‘very nonsense element in this exhibition, and in the claims gravely put forward for it’, and made his already considered opinions clear, for example, on the ‘worst’ of Matisse’s ‘art school tricks’ and also on Gauguin’s ‘strange grandeur’ and his ‘profound and real penetration into the wonders of a strange civilization’.

It was Sickert’s deep comprehension of the genesis of the more recent developments in the art of his day that made him so important for the younger generation within the Camden Town Group, even if they would soon reject the example of his particular practice and take new directions in their own. This would apply as equally to Lewis, who by 1912 was evolving in his own works towards the abstract, angular and facetted forms of the cubists, as it would to Gilman and to Ginner in their more overt engagements with the example of van Gogh at the time of Ginner’s Neo-Realist article in the New Age in 1914. Nonetheless, the firm belief that these artists continued to maintain was one that perhaps Sickert himself had instilled among them – that a painter’s fundamental concern was with the conditions of everyday life and with conveying in paint the very essence of that experience of modernity.

It is this broader vision of ‘Camden Town painting’, one inflected by the artists’ aims and study of the milieus in which they worked and in which their paintings were received, that informs The Camden Town Group in Context. Tate owns the largest and most significant public collection of art and archives relating to the Camden Town Group, and this research project grew from an earlier museum initiative to catalogue the group’s paintings and drawings in the museum’s collection.1 At the project’s heart lies an extensive study of the lives and works of core members of the Camden Town Group. Artists who were members briefly or whose work, particularly as represented at Tate, is better understood in other contexts, are not featured, though attention has been paid to the group’s circle of associates, notably excluded women artists, such as Stanislawa de Karlowska and Sylvia Gosse, and close friends, such as Douglas Fox Pitt and Albert Rutherston, in order to give a broader view of the group’s history and significance.

Readers of the catalogue entries will not only discover how the paintings were made but also enter into a world of coster girls (sellers of fresh produce from baskets or stands) on busy London streets, cab-horses (on the verge of being replaced by motor-taxis), fried fish shops (favoured by the working class), music halls (with their ribald and patriotic songs), and people at leisure or work within their homes (revealing the different domestic environments of those living and working in London at the time). Life in Britain was to change dramatically during the First World War and immediately afterwards, but this project points to the rapid and sometimes uncomfortable changes in British society that had already occurred in the early years of the twentieth century, marrying these broader narratives to the lives and aspirations of individual artists in the Camden Town Group.

Involving many disciplinary perspectives and presenting different types of research material, The Camden Town Group in Context aims to offer a multi-layered approach to re-evaluating the work of Camden Town artists today. Linked to the entries on individual works written by Tate curators, conservators and researchers are twenty-four newly commissioned essays by specialists in many fields. In addition, six texts of historiographic and scholarly importance have been selected for republication. To supplement these interpretations and to provide a resource for future study of the group’s works, the project also reproduces key primary research materials. These include the catalogues of the three Camden Town Group exhibitions and press reviews, as well as writings by artists and recollections of the group by contemporaries. Included, too, is a selection of letters in Tate’s Archive by key figures of the period – for example, Walter Bayes, Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Harold Gilman, Sylvia Gosse, Augustus John, Henry Lamb, James Bolivar Manson, Lucien Pissarro and William Rothenstein – as well as, for example, minutes and voting lists from meetings of the group and many previously unpublished photographs. Making use of the opportunities offered by online publishing, the project includes excerpts of films of London street scenes and of contemporary events, as well as popular music hall songs. Short films showing a conservator discussing the materials and techniques used in Camden Town paintings have also been made for the project.

Together, the project’s essays and materials take up the challenge of closely examining artworks within the wider context of a particular group of painters perceived by many to stand outside of the development of modern or, specifically, modernist art towards abstraction and which, as has been seen, tends to privilege a canon of primarily French paintings ranging from Manet to Matisse. Rather than attempting to position Camden Town Group art in relation to such a notional trajectory, this project has focused instead on the idea of what the art historian Lisa Tickner has termed ‘local modernisms’ and the specificity of individual artists’ engagement with the particularities of the experience of modern life in the Edwardian era. For Tickner, and for this project too, the point is to refrain from seeing British art as a ‘pallid reflection of developments elsewhere’ but to consider instead ‘the local inflections to the web of relations that make up the cultural field’.2 Thus Camden Town painting is examined here in the light of major themes – modernity and the metropolis, social class and social type, popular culture and performance, gender and sexuality, and life beyond the city – represented in the works themselves and of contemporary interest and sometimes concern.

David Peters Corbett’s essay explores representations of city scenes in Camden Town Group paintings. For him, these are often characterised by a sense of isolation and alienation, particularly within the constantly expanding suburbs including Camden Town in north London. Corbett contrasts these representations with those of the Ashcan painters in New York of the same period, bringing an important transatlantic dimension to the discussion of early modernism.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

In the context of artists’ and writers’ representations of modern life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the concept of the urban observer is a productive one. Deborah Longworth perceives the significance of a British tradition here, one extended from Charles Lamb and Charles Dickens in the 1830s. A concern with social types of all classes clearly emerges in Camden Town Group painting, amounting in some respects to a taxonomy of early twentieth-century London, which was then undergoing a considerable growth in population and seeing new trends in occupation and leisure. A parallel interest in the portrayal of social types within contemporary tendencies in early photography is discussed in Valerie Williams’s essay.

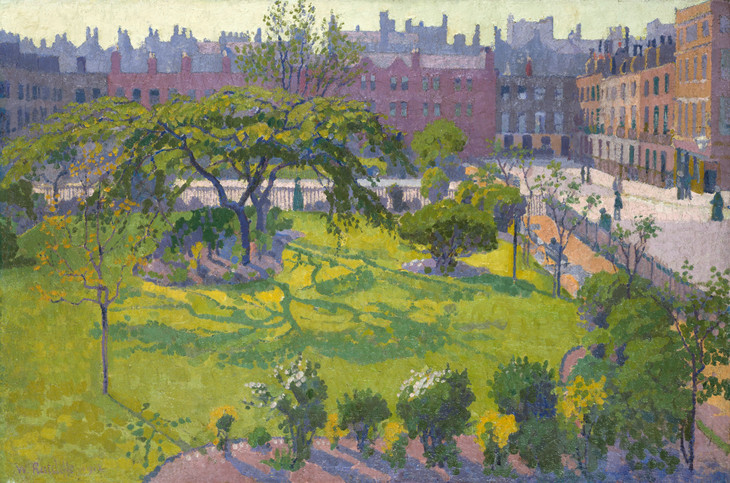

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Cinema was also a newly emerging form of popular entertainment in the period. Focusing on Sickert’s Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906 (fig.4), depicting the Middlesex Music Hall in Drury Lane, its cheapest seats in the gods transformed into a viewing space for a Wild West movie, and Malcolm Drummond’s In the Cinema 1913 (fig.5), Maurizio Cinquegrani’s essay traces changing attitudes to working class entertainment and education and the accompanying encouragement of a dutiful citizenship in the production of such films as Old London Street Scenes (1903), conveying the spectacle of newly redeveloped thoroughfares like the Strand, a space for imperial displays of pomp and circumstance as well as for fashionable consumption.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 730 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Gallery of the Old Mogul 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

In the Cinema 1913

695 x 695 mm

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

Fig.5

Malcolm Drummond

In the Cinema 1913

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

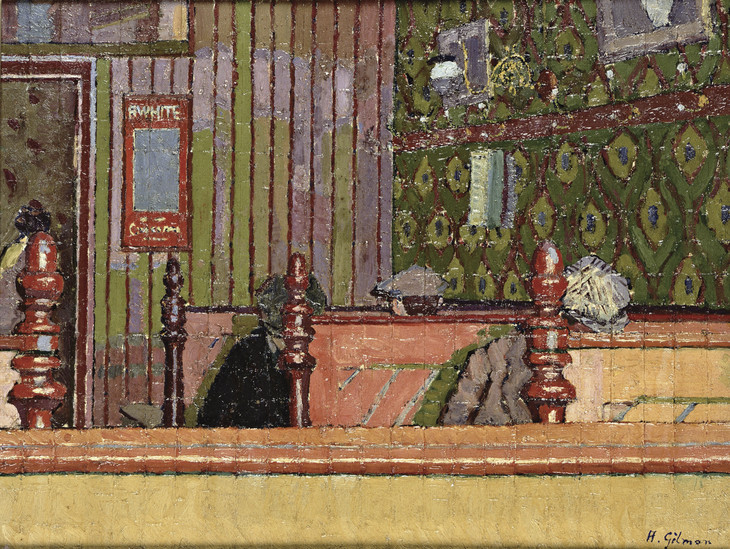

At the same time this era saw a widespread turn against the perceived cultural decadence and aestheticism of the 1890s – then closely associated with Sickert’s contemporary, the poet Arthur Symons – in favour of what Andrew Stephenson’s essay terms the ‘new codes of manliness’ and a form of (self-) representation that would specifically ‘re-masculinise’ English modernism. Contemporary interest in the classification of social life was reflected in the Camden Town Group’s apparent fascination with the relations between individual identities and specific spaces. Compare, for example, Ginner’s depiction of the Café Royal in Regent Street 1911 (Tate N05050, fig.6) – a favoured venue for London’s bohemians, artists, actresses and slumming aristocrats – with Harold Gilman’s An Eating House c.1913–14 (fig.7), which, as Alistair Smith discusses, records the city’s lower class, marginal characters.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Café Royal 1911

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 483 mm; frame: 878 x 725 x 100 mm

Tate N05050

Presented by Edward Le Bas 1939

© Tate

Fig.6

Charles Ginner

The Café Royal 1911

Tate N05050

© Tate

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.7

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

In keeping with the spirit of Gilman’s An Eating House, William Rough’s essay focuses on the experience of modernity that, as Corbett describes, was found in the often claustrophobic tedium of the suburb. Rough compares Sickert’s Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846, fig.8), with its ‘set’ choreographed, as it were, by the artist, to developing tendencies in the fashionable ‘New Drama’ of George Bernard Shaw and John Galsworthy, influenced by the northern European playwrights, Henrik Ibsen and Anton Chekhov. All shared a common interest in naturalist settings and in the observation of psychologically driven situations. Simon James charts parallel concerns in his essay with the changed conditions of modern life in the writings of H.G. Wells in particular.

To underline the particular importance to early twentieth-century artists of the wider Edwardian fascination with working class lives and sexuality, and also the importance of examining the interrelations between high and low cultures across the period, the project republishes Lisa Tickner’s study of Sickert and the Camden Town Murder series from 2000. This examines in close detail Sickert’s fascination with the murder of prostitute Emily Dimmock alongside popular press accounts and contemporary visual representations of sexual crimes. The contrast between explicit reports and images in periodicals, composed with reference to the conventions of Victorian and Edwardian melodrama, compare interestingly with Sickert’s paintings and drawings, showing the extent to which modern sensibilities were increasingly shaped by mass circulation imagery, scandal and titillation, with reference, too, to traditions in forms of art consumed in popular exhibitions.

Barnaby Wright’s essay extends discussion of the representation of female sexuality by reconsidering Sickert’s practice in relation to the conventions of the academic nude which had become comparable to the ‘living picture’ acts that were a popular music hall turn of the day. The article by Sickert that Wright discusses in most detail, ‘The naked and the Nude’ (1910), is one example of the artist’s erudite commentaries on the condition of contemporary art published in the periodical the New Age, the subject of Anna Gruetzner Robins’s essay.

Questions of definition in relation to the group as a whole are, of course, fundamental to the project, which includes, for example, consideration of women artists who were debarred from actual membership. As Juliet Kinchin, Meaghan Clarke and Nicola Moorby all variously demonstrate in their essays, attention to the art of these women – of Robert Bevan’s wife, Stanislawa de Karlowska, along with that of Sickert’s friends Sylvia Gosse, Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands – is essential to a clearer understanding of the complex motivations and underlying attitudes of members of the group at a time of suffrage agitation and the emergence of the modern woman.

A significant number of Camden Town Group paintings focus on the domestic interior, often scenes of dramatic tension or claustrophobic tedium, and of intimate nudes. Emma Chambers’s essay on the Slade School of Fine Art’s influence on the group (over half its members trained there) comments on the extent to which these interior paintings were anticipated by a Slade tradition of the 1890s, and connections to the French artists Vuillard and Bonnard are also observed. Interior studies are also the particular focus of Kinchin’s essay. As she observes, from scullery to drawing room, the domestic interior in the British home was inextricably linked to social and moral values, gender roles, economy and the function of taste. The audience for these paintings she terms ‘artefactually literate’. Colour schemes, furniture types, textures and ornaments all contribute to the formation of specific ‘room-types’ whose meanings were read against the character of their inhabitants – in some cases conveying the dullness of overly prescribed lives – as at times revealed in paintings by both Gore and Gilman. By contrast, for more independent women artists like Sands and Vanessa Bell, the domestic interior was a space where they could exercise their own creativity and enter into conversation and the exchange of ideas, as explored in Nicola Moorby’s essay.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Nearing Euston Station 1911

Oil on canvas

498 x 600 mm

King’s College, Cambridge, on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum

Photo © The Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Fig.9

Spencer Gore

Nearing Euston Station 1911

King’s College, Cambridge, on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum

Photo © The Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

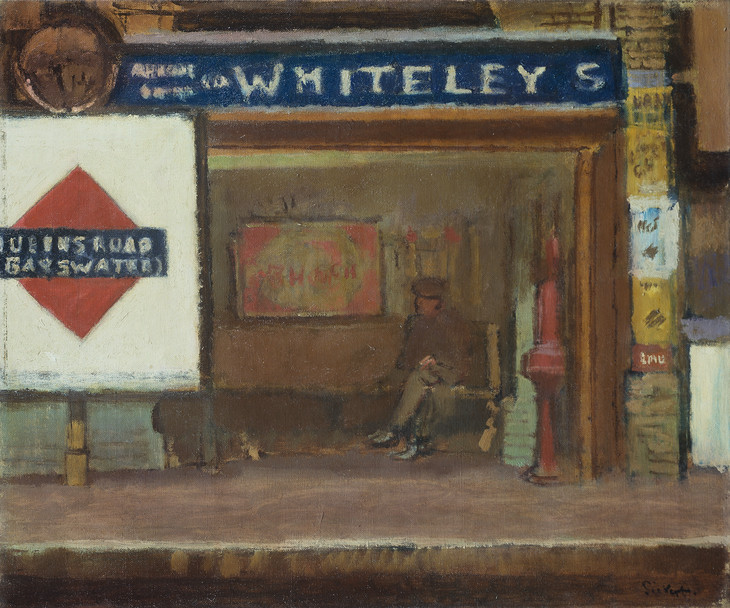

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Queen's Road, Bayswater Station c.1916

Oil paint on canvas

623 x 730 mm

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

Queen's Road, Bayswater Station c.1916

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Just as social, gender and spatial identities within the city were transforming throughout these years, so, too, were the relations between city and country, and again the character of Camden Town Group paintings underlines these developing tendencies. Both Gore’s and Sickert’s paintings of north London stations and railway lines indicate that ever greater mobility was a marked feature of the Edwardian era, with rapid transport not just across the city but also beyond it into the countryside to rural sites and resorts heavily advertised at underground and railway stations (figs.9 and 10). With the advent of motor cars after 1911, the countryside was increasingly accessible as a site of leisure and pleasure, reducing some of the nostalgic longings that circulate around ruralist cultures of even a few years earlier. As Helena Bonett’s and Ysanne Holt’s essays observe, ruralism in the Edwardian era was significantly redefined as a result of this wider access and mobility. In a rural subject like The Beanfield, Letchworth 1912 (Tate T01859, fig.11), Gore, more commonly perceived as a painter of realist urban scenes, produced one of his most technically innovative, modernist representations.

Following the deaths of Gore in 1914 and Gilman in 1919, with the events of the First World War in between, the significance and fundamental principles of Camden Town Group painting might have been forgotten. The strong legacy of the group for the development of British art, however, is considered by Martin Hammer. As he observes, the commercial art market sustained interest in their paintings in the 1930s, a time when realism was for some perceived as an important antidote to both abstraction and surrealism. As he underlines, too, this was most often a socially committed, not a parochial, position. To some extent, this paralleled tensions in the early period between Camden Town and Bloomsbury painting with the latter’s advocacy of ‘significant form’ before 1914. Looking beyond the 1930s to the post-1945 Kitchen Sink paintings of such artists as John Bratby and later to the interest in Sickert of Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon, Hammer emphasises the extraordinary importance of this turn-of-the-century group of artists whose observations of the everyday had a resonance and legacy which extend beyond the realm of the painterly, and might be recognised in the drama of the commonplace as perceived by a number of contemporary artists today.

Begun in the 1990s, the original cataloguing project was intended to form part of a projected series of hardback volumes on aspects of Tate’s collection and latterly as a volume focusing only on paintings by the Camden Town Group. Plans changed in 2007 when Tate determined that all collection catalogues and research projects would be published online, and, with the support of the Getty Foundation’s Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative, the project was reconfigured and expanded in preparation for online dissemination in 2009.

How to cite

Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt and Jennifer Mundy, ‘Introducing The Camden Town Group in Context’, May 2012, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www