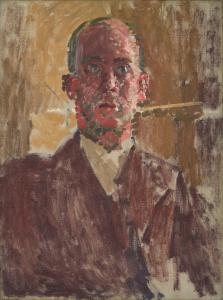

Harold Gilman Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table 1916-17

Harold Gilman,

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table

1916-17

The subject of a number of portraits by Harold Gilman, Mrs Mounter lodged at the same address as the artist at 47 Maple Street, off Tottenham Court Road. In this painting her direct gaze and time-worn features, highlighted in warm tones and haloed tightly by an orange kerchief, draws the viewer in. The ordinary crockery on the table indicates the unceremonious sharing of breakfast across social classes and despite wartime shortages.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table

Exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 405 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1942

N05317

Exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 405 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1942

N05317

Ownership history

... ; Hugh Blaker (1873–1936) by 1928; inherited by his sister, Miss Jenny Blaker, from whom bought through Leicester Galleries, London, by Tate Gallery 1942.

Exhibition history

?1916

Fifth Exhibition of Works by Members of the London Group, Goupil Gallery, London, November–December 1916 (109, as ‘Portrait of Mrs Mounter’).

1917

Sixth Exhibition of the London Group, Mansard Gallery, Heal’s, London, April–May 1917 (41, as ‘Portrait of Mrs Mounter’).

1919

Tenth Exhibition of the London Group, Mansard Gallery, Heal’s, London, April–May 1919 (no number).

1919

Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919 (9 or 21, both as ‘Mrs Mounter’).

1928

Contemporary British Art, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, October–December 1928 (167, as ‘My Landlady’).

1929

The Hugh Blaker Collection, Platt Hall, Rusholme, Manchester, May–June 1929 (53), Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, September–October 1929 (26).

1930

The Camden Town Group, Leicester Galleries, London, January–February 1930 (16).

1934

Paintings by Harold Gilman 1876–1919, Arthur Tooth & Sons, London, September–October 1934 (12, as ‘Mrs Mounter’).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–June 1942 (35), (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, August 1943 (16).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946, Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946, Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (13, reproduced), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946, Akademie der Bildenen Künste, Vienna, September 1946, Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946, Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw, November–December 1946, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (12, reproduced).

1947

Tate Gallery 1897–1947: Pictures from the Tate Gallery Foundation and Exhibition of Subsequent British Painting, Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (5317, reproduced pl.9).

1947–8

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (Arts Council tour), Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 1947, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1947, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1947, Bristol City Art Gallery, January–February 1948, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth, February–March 1948, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, March–April 1948, Plymouth Art Gallery, April–May 1948, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–June 1948, Huddersfield Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1948, Aberdeen Art Gallery, July–August 1948, Salford Art Gallery and Museum, August–September 1948 (6, reproduced).

1960

British Painting 1700–1960, (British Council tour), Pushkin Museum, Moscow, May–June 1960, Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, June–July 1960 (93).

1964

London Group 1914–64: Jubilee Exhibition, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, July–August 1964, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, August–September 1964, Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery, October 1964 (16).

1981–2

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, (Arts Council tour), City Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, October–November 1981, York City Art Gallery, November 1981–January 1982, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, January–February 1982, Royal Academy of Arts, London, February–April 1982 (76, reproduced on front cover).

1984–5

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, July 1984–November 1985 (long loan).

1998–9

An Ordinary Life: Camden Town Painters, Aberdeen Art Gallery, November 1998–January 1999 (12).

2002

Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe, Southampton City Art Gallery, April–July 2002 (no number).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (55, reproduced).

References

1916

Frank Rutter, Sunday Times, 19 November 1916.

1916

Daily Telegraph, 29 November 1916.

1916

Athenæum, December 1916.

1917

Frank Rutter, Sunday Times, 29 April 1917.

1919

Clive Bell, Athenæum, 29 April 1919.

1919

Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London 1919, pp.26–30, 31.

1922

Frank Rutter, Some Contemporary Artists, London 1922, p.135.

1930

Joseph Duveen, ‘Thirty Years of British Art’, Studio, London 1930, reproduced p.79.

1950

Allan Gwynne-Jones, Portrait Painters, 1950, reproduced pl.149.

1952

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, p.154 n.3.

1954

J. Wood Palmer, ‘Introduction’, in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1954, p.5.

1962

John Rothenstein, The Tate Gallery, London 1962, reproduced p.101.

1962

John Rothenstein, British Art since 1900: An Anthology, London 1962, reproduced pl.16.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.235–6.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and His Circle, London 1971, p.129, reproduced pl.23.

1973

William Gaunt, A Concise History of English Painting, London 1973, reproduced pl.175.

1975

An Exhibition of the Bevan Gift of Paintings and Drawings by the Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Camden Arts Centre, London 1975, [p.6].

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, pp.129, 131, 147.

1981

Times Higher Education Supplement, 6 November 1981, reproduced p.10.

1982

Observer, 31 January 1982, reproduced.

1987

Celina Fox, Londoners, London 1987, pp.136–7.

1991

Bernadette Nelson, The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1991, pp.5, 9.

1996

Robert Upstone, Treasures of British Art: Tate Gallery, New York and London 1996, reproduced p.239.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.169–70.

2001

Richard Humphreys, The Tate Britain Companion to British Art, London 2001, p.171, reproduced.

2002

Richard Shone, ‘Southampton: Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe’, Burlington Magazine, vol.144, no.1192, July 2002, p.443, reproduced fig.60.

2003

Giles Waterfield and Anne French (eds.), Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London 2003, pp.117–9.

2003

Jane Humphrey (ed.), The London Group: Visual Arts from 1913, London 2003, p.9.

2010

John Rolfe, ‘The Identification of the Sitter in Harold Gilman’s Portraits of Mrs Mounter’, Burlington Magazine, vol.152, no.1285, April 2010, pp.236–8, reproduced p.236.

Technique and condition

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The cloth has a plain open weave and is probably linen. The threads are saturated and darkened by an applied liquid, which may be oil from the priming or overlying layers. The canvas has an extremely thin glue sizing that coats the individual fibres but does not form a continuous film. The priming extends to the cut edges on three sides and stops short of the bottom edge, which has holes from looming the canvas for priming. The fluid off-white primer saturated the canvas leaving a thin coat on the face and penetrating to the back in pools. It consists of a single opaque layer of white primer, probably bound in oil. The resulting painting surface is slick and retains some canvas texture, while the saturated canvas is stiff and slightly distorted by the contracting pools of primer on the back. The primed canvas is stretched onto the four-member stretcher and secured with coated steel tacks, in their original positions. The prepared support is consistent with all those found on Gilman’s paintings in the Tate collection (see also Tate T00096).

There are visible pencil marks at one-inch intervals along all four edges. They are the remnants of a grid on the primed canvas, used to transfer and enlarge the composition from a drawing. A related squared-up drawing with the same title is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.1 It is approximately half the size of the canvas and with many differences in detail. No initial drawing in pencil or ink remains visible on the canvas. The composition is outlined in thinned blue paint that is still detectable in areas around the cups. The main colouring is built up in multiple layers of paint in most areas, to achieve the colour and surface Gilman sought. The direction and integrity of each carefully considered brushstroke is retained in the softened texture of the dried paint. Even with this build-up of paint, occasional areas of primer remain visible around the perimeters of forms, enlivening the surface with their sparkle.

Gilman’s use of paint reinforces the solemnity of his static forms. Each main form is clearly demarcated, often with coloured outlines, such as those around the vibrant orange headscarf that frames Mrs Mounter’s head. Each object is modelled in simplified planes of heightened colours, evoking the play of light on solid forms, as with the complex range of cool green to warm pink facets of the face. A glossy layer of soft resin varnish was applied to saturate the colour which may have dulled unevenly on drying. It accumulated in the texture of the painting and discoloured a little with age, emphasising its unevenness and moderating the contrast of the hues and tones. It is not known whether it was applied by the artist.

There are pin holes surrounded by slight circular indentations in the paint near each corner. These were made while the paint was still soft and are probably from the use of canvas separators for storage and transport.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

June 2005

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table Exhibited 1917 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, revised by Helena Bonett, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Mrs Mounter lodged at 47 Maple Street, off Tottenham Court Road, London W1, where Harold Gilman also lived from 1914 to 1917. Research by the art historian John Rolfe indicates that the sitter is Ann Emma Mounter, née Townsend (1850–1932), who stayed at 47 Maple Street with her husband Frederick at this time, and who may have occasionally undertaken housekeeping duties for Gilman.1

Maple Street crosses Fitzroy Street, and so the house, which no longer exists, was very close to 19 Fitzroy Street, where Gilman and other members of Walter Sickert’s group showed their work. Sickert’s etchings Maple Street c.1923,2 and O Sole Mio c.1923,3 show the corners of Maple, Cleveland and Southampton streets, and it is possible that they depict where Gilman lived. Both prints were based on an initial drawing made in c.1917, perhaps while Gilman was still living there (Aberdeen Art Gallery).4 However, by the time Gilman painted Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table he and Sickert, once his hero, had become somewhat alienated from one another. Gilman’s use of a bright palette and pure colour was not to Sickert’s taste. Gilman ‘would look over in the direction of Sickert’s studio’, Wyndham Lewis recalled,

and a slight shudder would convulse him as the thought of the little worm of brown paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, no emerald greens, vermilions, only, as it, of course, should do. Sickert’s commerce with these condemned browns was as compromising as intercourse with a proscribed vagrant ... bituminous painting, dirty painting, was the mark of the devil ... But he always retained a great respect for the virtues of his first real master.5

The neighbourhood around Fitzroy Street was a somewhat transient area. Noting the prostitutes found slightly further south towards Oxford Street, Charles Booth (1840–1916) walked the area in 1898, making observations in his notebook of its social mix for his survey of London poverty. He noted:

Some servants. 4½ st.[orey] apartments. ‘The heart of foreign club land’. Some gambling & some respectable clubs. ‘Foreigners are directed to these clubs by their consuls; that is why foreigners drift this way.’ Fitzroy Club at east side of doubtful respectability.6

Gilman’s lodgings in 47 Maple Street consisted of a pair of rooms, probably on the first floor, divided by wooden doors. Before the house was split into flats, these rooms had probably been the drawing room. Gilman used the rear part for his studio, while the larger front section contained a circular dining table and his bed. The layout of the apartment is seen in a pair of his pictures, Tea in the Bedsitter 1916 (fig.1) and the Ashmolean’s Interior with Mrs Mounter 1916–17 (fig.2).

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Tea in the Bedsitter 1916

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 910 mm

Huddersfield Art Gallery

Photo © Huddersfield Art Gallery

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Tea in the Bedsitter 1916

Huddersfield Art Gallery

Photo © Huddersfield Art Gallery

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Interior with Mrs Mounter 1916–17

Oil paint on canvas

695 x 950 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Interior with Mrs Mounter 1916–17

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Subject and composition

The first appearance of Mrs Mounter as the subject of any of Gilman’s exhibited works was at the November–December 1916 London Group exhibition, where he showed what was probably a drawing priced £5, and a more expensive picture at £35 that was undoubtedly an oil.7 Gilman made three oil portraits of Mrs Mounter. The earliest is likely to be the small picture now in Leeds City Art Gallery (c.1916).8 It shows her seated but half-turned and from a higher viewpoint than Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table, as if Gilman was standing at his easel looking down on her. She is dressed in the same coat and headscarf as in the Tate’s picture, and this would appear to be a preliminary approach to a subject that was subsequently refined and made more rigorous in its design.

Tate’s picture is identical to a larger version in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, the only differences being its slightly brighter palette and the addition of a William Morris chair on the right (c.1916–17).9 The artist’s widow Sylvia Gilman believed that the Tate picture was made first.10 A squared drawing in the Ashmolean Museum is the preliminary drawing for the Walker Art Gallery version of Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table.11 It is difficult to be certain if either of these two versions were included in the 1916 London Group exhibition in which Mrs Mounter pictures were included, but Tate’s painting was included in the April–May 1917 show held at the Mansard Gallery in Heal’s, just across Tottenham Court Road from Gilman’s lodgings.

Gilman painted two other pictures of Mrs Mounter in which she appears as a middle-distance figure in the Maple Street interior, Interior (Mrs Mounter) c.1916–17 (private collection)12 where she is viewed from behind, and the haunting Interior with Mrs Mounter 1916–17 (see fig.2), where she stands posed between the two sections of Gilman’s rooms, looking back enigmatically at the viewer.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Oil on canvas

460 x 610 mm

Private collection

Fig.3

Harold Gilman

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Private collection

William Hogarth 1697–1764

Heads of Six of Hogarth's Servants circa 1750–5

Oil on canvas

support: 630 x 755 mm; frame: 883 x 1009 x 65 mm

Tate N01374

Purchased 1892

Fig.4

William Hogarth

Heads of Six of Hogarth's Servants circa 1750–5

Tate N01374

Influences

In Some Contemporary Artists (1922), Gilman’s friend Frank Rutter drew particular attention to his pictures of Mrs Mounter:

Sometimes I think that more wonderful than anything else he did are the two portraits he painted of his landlady in Maple Street, Mrs Mounter. They have the reverent psychology of a Rembrandt with the colour of a Vermeer. These portraits are the apotheosis of the charwoman, the transfiguration of homeliness, age, and toil into a spiritual loveliness of colour that time cannot wither ... in these we get the whole of Gilman, the whole at his deepest and richest, of the painter we valued and of the man we loved, of the great colourist with his magic of harmony, and of the great-hearted democrat with his tenderness and love for all humanity.16

Vincent van Gogh 1853–1890

La Berceuse (Portrait of Madame Roulin) c.29 March 1889

Oil paint on canvas

910 x 720 mm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

Fig.5

Vincent van Gogh

La Berceuse (Portrait of Madame Roulin) c.29 March 1889

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

However, an altogether closer source of reference for the painting was one of Gilman’s own pictures. Among his earliest known works is Portrait of a Woman in Black c.1902–4 (private collection).22 Remaining in the Gilman family, it was believed to be a portrait of the artist’s grandmother, Amelia Gilman. Wearing black, and set against a slightly less black background, the seated woman looks directly out at us just like Mrs Mounter, and has similarly lumpy and lined features. Gilman evidently had in mind the portraits of Velázquez he had recently seen in the Prado, although there is also a striking similarity to the work of Edouard Manet.

The First World War

It is worth remembering that Gilman painted his pictures of Mrs Mounter during the First World War. In November 1916, the earliest date that Gilman might have painted Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table, the Battle of the Somme came to an end. Lasting from 1 July to 18 November, the battle claimed an estimated 420,000 British lives for an advance of just twelve kilometres.23 Gilman’s brother Leofric was serving in the forces,24 and Mrs Mounter’s son, Henry Edmund Mounter (born 1889), had likewise left for war in 1915.25

In January 1916 the government introduced the Military Service Act. Voluntary enlistment was not keeping up with casualty rates, and conscription was essential. The Act directed that men aged between eighteen and forty-one were liable for military service, unless they were married or in a reserved occupation. An amendment passed shortly after abolished exclusion because of marital status, and also gave the government the right to re-examine men previously physically exempted on health grounds.26 Gilman’s fortieth birthday was on 11 February 1916, and therefore notionally he was liable to be called up when the Military Services Act came into force. But his club foot and history of ill-health in his youth meant he was not selected. It is not known whether he attended a tribunal for exemption. There is no record of Gilman being engaged in war work of any kind, until his commission to paint Halifax Harbour in 1918 by the Canadian War Records Office.27 Throughout the war, Gilman’s life must have continued much as it had done before. In the summer of 1917 he married Sylvia Hardy, one of his former students at Westminster School of Art, and moved to Hampstead. Being an un-uniformed man in London, not engaged in helping the war effort, must perhaps have raised questions in his mind about the role of the artist in society and exclusion from what men of a slightly younger age were going through in the trenches. The practice of handing out white feathers for cowardice to men of serviceable age not in uniform gathered pace in 1915 and 1916 as popular perception of the troop shortage grew. Even men on leave were sometimes accosted in this way, often by female members of the Organisation of the White Feather set up by Admiral Charles Fitzgerald in the first month of the war. The government’s response was to issue all those in reserved occupations with a ‘King and Country’ badge which proclaimed their exemption from the armed services.28 Whether Gilman was issued with such a badge as an art teacher is unknown, but is perhaps unlikely.

By the time Gilman painted Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table, German attacks on shipping were beginning to interfere greatly with Britain’s food supply. Although the German fleet never again left port after the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, concerted submarine attacks were able to cut off British lines of supply. On 31 January 1917 Germany announced its reintroduction of unrestricted submarine warfare which targeted both neutral and enemy ships alike. The intention was effectively to starve Britain into submission, and 230 supply ships were sunk in February 1917. The following month a record 500,000 tons of shipping were sunk, but Britain managed to boost its wheat production that summer and the population was fed.29 Food was nevertheless in short supply and by 1918 a variety of staples such as butter, sugar and jam were rationed.30 It is against this background of dwindling food supplies that Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table might partly be viewed. It makes the sharing of breakfast a poignant connection between the artist and what may have been his charwoman. Tea in particular was hard to come by. Although never rationed it was difficult to obtain because it was imported from India and the Far East. Gilman’s family had connections with the tea trade; his grandfather Ellis founded a tea company in Hong Kong,31 and Gilman’s brother Leofric worked in Hong Kong, perhaps for the company, until 1914.32

Elegant conversation-piece paintings of tea served to grand sitters, such as Hogarth’s The Strode Family c.1738 (Tate N01153) or George Morland’s The Tea Garden c.1790 (Tate T00055), were relatively common in eighteenth-century British art, as Gilman was no doubt aware. It was a subject that recurred in twentieth-century painting, and at the Royal Academy in 1916 he may even have seen The Tea Party (‘Nanny, Bessie and John’) by his Slade contemporary Hilda Fearon (Tate N04832). This presents a comfortable image of a middle class ceremony continuing without the ravages of the First World War being allowed to intrude in any way. Gilman offers a rather different subject. At his table, tea is served not in the best china, but from a standard, utility-type teapot known as a Brown Bessie.

Ownership

Hugh Blaker (1873–1936),33 the first recorded owner of Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table, who also owned Gilman’s Lady on a Sofa (Tate N05831), was born in Worthing in Sussex. After studying painting in Antwerp and Paris, in 1905 he became curator of the Holburne of Menstrie Museum in Bath. He retired in 1913 and became a noted dealer and collector, as well as a sometime writer, actor, poet, critic and philosopher. Notably, he advised the Davies sisters on the building of their picture collection, which was bequeathed to the National Gallery of Wales, Cardiff. He was one of Gilman’s most important patrons, buying The Old Lady (City Art Gallery, Bristol) and Mountain Bridge, Norway (Museum and Art Gallery, Worthing). His collection was exhibited in 1929 at Platt Hall, Rusholme, Manchester, May–June, and at Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, September–October, and the catalogue lists a number of other oils by Gilman including Still Life, The Seamstress, Snow Scene,34 Interior, Portrait of a Girl, The Eating House, Mary L.,35 and A Girl’s Head. Blaker also owned pictures by other Camden Town Group painters, including Gore, Ginner, Bevan, Manson and Sickert, as well as works by Gertler, Grant, Augustus John, Innes, Strang, Roberts, Bayes, Greaves and Whistler. The Leicester Galleries in London showed a selection of works from his collection in March 1948.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Revised by Helena Bonett

January 2011

Notes

John Rolfe, ‘The Identification of the Sitter in Harold Gilman’s Portraits of Mrs Mounter’, Burlington Magazine, vol.152, no.1285, April 2010, pp.236–8.

Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, no.212.

Notebook B355, pp.87, 129, Booth Collection, Archives of British Library of Political and Economic Science, London School of Economics. Booth’s quotation marks suggest he walked the area with a police officer, as he often did in such surveys, and that these are the policeman’s observations rather than Booth’s.

Fifth Exhibition of Works by Members of the London Group, Goupil Gallery, London, November–December 1916 (54 and 109).

Reproduced in Leeds’ Paintings: 20th Century British Art from Leeds City Art Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1980 (18).

Reproduced in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, p.124.

See Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.235–6.

Reproduced in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981 (68 and back cover).

Reproduced in Modern British & Irish Paintings, Watercolours and Sculpture, Christie’s, London, 11 March 1994 (59).

Ysanne Holt, ‘An Ideal Modernity: Spencer Gore at Letchworth’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, p.92.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne, son art – son oeuvre, Paris 1936, no.687; reproduced in Cézanne, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1996 (137).

See William H. Beveridge, British Food Control: Economic and Social History of the World War, London and Oxford 1928.

For an account of his life, see John Ingamells, The Davies Collection of French Art, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff 1967, pp.19–22.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

- From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group Juliet Kinchin

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

- The Camden Town Group: Then and Now Ysanne Holt

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’ in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London: Chatto & Windus 1919, pp.19–32.

Related film

-

Conservator Stephen Hackney on Harold Gilman's Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917© 2011 Tate

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table Exhibited 1917 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, revised by Helena Bonett, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www