The Socio-Geography of Art Dealers and Commercial Galleries in Early Twentieth-Century London

Anne Helmreich

The exhibition culture of London in the early years of the twentieth century played a determining role in the formation of the Camden Town Group. Anne Helmreich views the group’s exhibitions in the context of the social geography of London’s dynamic art market.

The Camden Town Group’s decision to hold three key exhibitions at the Carfax Gallery must be understood within the context of the rising significance of exhibition culture and the socio-geography of the art market in turn-of-the-century London. Artists seeking to make their way in London at this moment were confronted by a plurality of exhibiting opportunities, ranging from the formal structures of juried exhibitions organised by artists’ societies to commercial art dealers and ad hoc, newly emergent formations. Indeed, the entrepreneurial possibilities of the London art market arguably distinguished it from its counterparts in other major urban centres. As James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s activities demonstrate, adroit artists could exploit these multiple opportunities, eschewing loyalty or exclusivity to a single venue or dealer.1

This essay examines the firms favoured by the Camden Town Group artists – the Chenil, Carfax, Goupil, Doré and Leicester galleries – in the context of the dynamic and escalating art trade, and focuses on the local conditions in which these commercial art firms were situated. Such local conditions must be understood within the larger processes of economic growth, fuelled by the late industrial revolution, and the highly developed infrastructure of finance, transportation and communication (including print culture) that shaped London and the international networks in which the city’s retailers and merchants participated.2

Exhibition culture

Exhibitions had long been a key strategy for the display of artistic production to the public in order to facilitate critical commentary and commodity consumption as well as to construct artistic reputation. The Royal Academy, for example, shortly after its founding in 1768, had quickly adopted highly visible and deliberately staged juried exhibitions in which ‘a premium’ was placed ‘on innovation and individuation’.3 Over the course of the nineteenth century, artist-run societies and clubs dedicated to exhibiting proliferated.4 Exhibitions began to appear around the year, expanding beyond the traditional focus on the social season. By the early twentieth century, the Art News could report that

the artist knows full well that exhibiting is not a matter of choice, but of necessity. The more his work is seen, the wider will the recognition accorded to him, the greater his opportunities of effecting sales.5

In addition to patronage, exhibitions helped to garner critical attention. At the turn of the century, criticism could be found across a wide range of publications, from newspapers and specialist art journals to the modernist little magazines.

The art dealer

By the 1880s artist-run societies were in stiff competition with the activities of the commercial art dealer. Indeed, Walter Sickert argued that the exhibiting societies were eclipsed by dealers who presented to the public art more worthy of critical attention:

It is natural that it should be at Christie’s and at the dealers’, rather than on the walls of the exhibiting societies, that we have to look for the material of criticism. In the former places two things have necessarily been eliminated. The more menial productions of uninspired portraiture have duly gone where compliments, more or less successful, are intended to go, to their peaceful and obscure addresses. The picture of the year has had its ‘notices,’ and either has or has not found its tomb in some long-suffering public gallery. Neither the one nor the other find, or is even intended to find, its way into the collector’s market. Both are sifted out, year by year, from the proper domain of criticism, which has other cats to whip.6

The commercial art dealer – the agent who profited from the primary and secondary trade in art trafficked from a permanent premises or shop – arose largely in the nineteenth century. Dealers capitalised on both the increased availability of art for trade and the growth of the middle and upper classes interested in attending exhibitions and acquiring reproductive engravings or original works. The art press helped to stimulate these processes, encoding artworks with educational and social values and eventually even participating in their fiscal valuation (although this often remained a troubled point for many art critics).

The commercial art gallery, which typically originated from selling artists’ supplies or print publishing, quickly adopted the strategy of the exhibition and associated practices, such as erudite exhibition catalogues. Commercial dealers were also alert to emerging techniques of advertising and marketing.7 However, they were also keen to position themselves as professional experts rather than shopkeepers.

The two chief trading objects for the commercial gallery were prints and easel paintings, the latter small in scale as compared to those associated with the Royal Academy and Paris Salon. As Walter Sickert noted in the Speaker in 1897, ‘If painters are to make a living, they will have to learn to work on a small scale. The exhibition picture has had its day.’8 This shift in size was in concert with the tastes of the day:

now consider the conditions under which your true collector, your connoisseur with a palate, buys. His space is limited, and, like a man with little time to spare, he will naturally ask the painter to put his thoughts into the smallest compass necessary to their complete expression.9

The Camden Town Group exhibitions easily fit into this paradigm. The critic Huntly Carter, in his review of the June 1911 exhibition, noted that ‘under the guise of an exhibition of pictures for the small buyer, it was really an artistic entertainment raised to a high pitch’.10 Carter’s comment underlines that art exhibitions were visual spectacles and occasions of social as well as fiscal exchange. The press functioned in a dual role in this context, both offering critical commentary on the works displayed and fuelling the celebrity culture in which art was increasingly embedded.

In 1911, the year of the Camden Town Group’s first exhibition at the Carfax Gallery, over 300 commercial art galleries were located in London, an index of the city’s concentration of art capital that closely correlated to its position as the leading international financial centre.11 For comparison, early twentieth-century Paris, according to Malcolm Gee, hosted about 130.12 The London houses encompassed a wide variety of firms, from picture restorers and framers who dabbled in selling art on the side, to well-established commercial dealers, such as Wallis & Son, who had acquired Ernest Gambart’s French Gallery. The advertising pages of the Year’s Art of 1911 reveal the most ambitious: Netherlands Gallery, Leicester Galleries, Carroll Gallery, Colnaghi & Obach, Doré Gallery, William Dowdeswell, Duveen Brothers, Fine Art Society, Frost & Reed, Gooden & Fox, Frederick Hollyer, Goupil Gallery, Isaac Mendoza, the Shepherd Brothers, and Wallis & Sons.

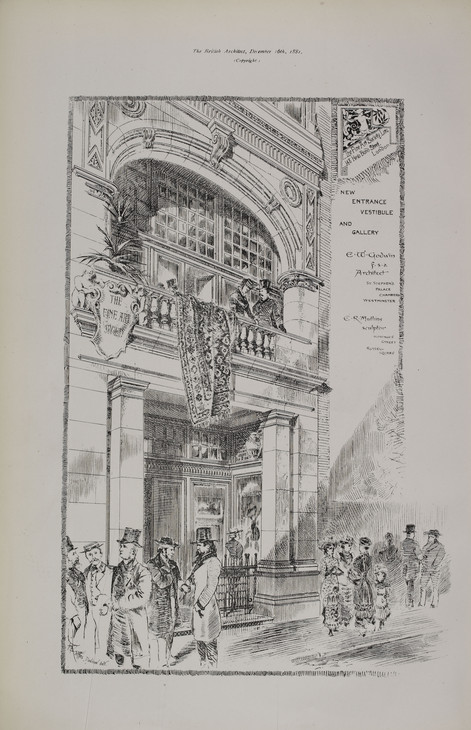

T. Raffles Davison 1853–1937

The Fine Art Society: New Entrance, Vestibule and Gallery 16 December 1881 British Architect

British Library, London

Photo © British Library, London

Fig.1

T. Raffles Davison

The Fine Art Society: New Entrance, Vestibule and Gallery 16 December 1881 British Architect

British Library, London

Photo © British Library, London

The Carfax Gallery, established in 1899 and home of the Camden Town Group shows, was part of the new crop of commercial galleries that sprang up around the turn of the century.14 Like Goupil, Thomas Agnew & Sons, Arthur Tooth & Sons and Colnaghi and Co., the Carfax blended displays of modern artists, largely British or French, with works by Old Masters and antiquities, and even played a crucial role in renewing interest in the art of William Blake with a key exhibition of his work in 1904 .

Founded in 1903, the Leicester Galleries, where many of the artists affiliated with the Camden Town Group showed as individuals, was also part of this new wave of galleries. Like the Carfax, its association with the progressive artists of the Camden Town Group may obscure ways in which it functioned in a similar fashion to other commercial galleries of the day. It relied at times, for example, on the tried and tested formula of commercially safe displays of topographic art, such as the 1902 exhibition of works by Trevor Haddon entitled Pictures of Spain. Its intention to compete with the dealers around St James’s Square and New and Old Bond Street was signalled by a Whistler exhibition in 1903, and displays of works from the Staats Forbes collection, including Jean-François Millet drawings (1906) and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Barbizon School works (1906). It likewise adopted the strategy of interspersing exhibitions of modern works with works by the previous generation, Old Master exhibitions, and shows by well-known artists, such as George Clausen. It also invited prominent critics, such as Frederick Wedmore, F.G. Stephens and Laurence Binyon, to write exhibition catalogues.15 Sickert, for example, penned a prefatory note for the catalogue for Walter Bayes’s exhibition in March 1918.16

By contrast, the Chenil Gallery, opened in 1905, was unique in its exclusive focus on contemporary art. Directed by Jack Knewstub, former administrator of the Chelsea School of Art, the gallery initially relied heavily on Augustus John for its success. John exhibited both prints and oils there, used its printing press, suggested other artists such as J.D. Innes and Eric Gill for exhibition, and directed patrons such as John Quinn and Lady Ottoline Morrell to the firm.17

Kunsthalle

In addition to these firms, several venues, such as the Dudley, Doré and Grafton galleries, functioned as ‘Kunsthalle’ – a site designated for temporary exhibitions. This Kunsthalle model was arguably more prevalent in London than has been previously recognised.

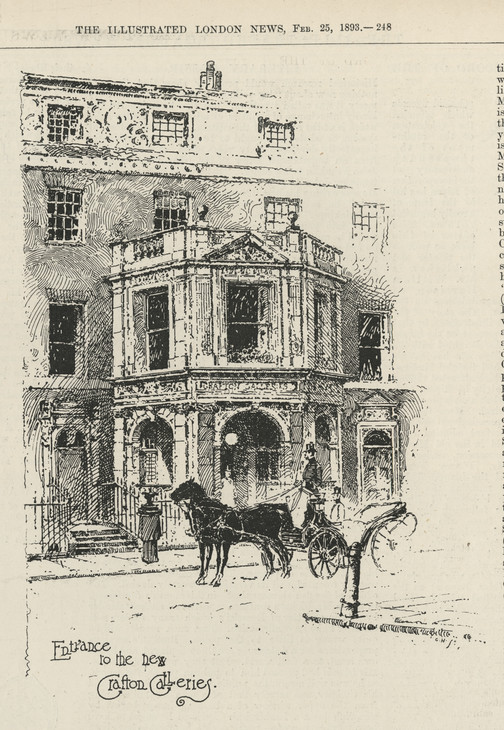

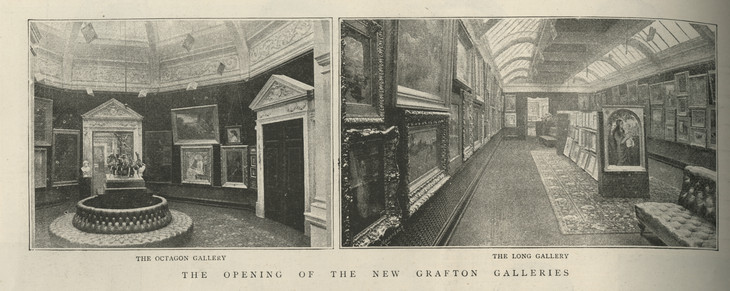

The Opening of the New Grafton Galleries 25 February 1893 Graphic, vol.47, p.184

Fig.2

The Opening of the New Grafton Galleries 25 February 1893 Graphic, vol.47, p.184

The Doré Gallery was established on New Bond Street in 1868 by Messrs Fairlees and Beeforth to showcase the works of its namesake, Gustave Doré. By the early 1900s, under the management of Joseph Fishburn, the gallery also hosted an eclectic series of rotating exhibitions in its six large galleries, including recent work by Walter Crane (1902); a London Salon of colour etchings and engravings organised by the Galleries Georges Petit (1907); and the Post-Impressionist Poster Exhibition and Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, both organised by the influential art critic Frank Rutter (1913).18

to carry on the business of proprietors for the exhibition of pictures, sculpture, and works of art generally, and of refreshment rooms and rooms for public and private concerts, receptions, or parties of any kind where music, dancing, or other entertainments may be provided.19

Roger Fry was hired as an advisor to the firm and eventually organised the crucial modernist exhibitions held there: Manet and the Post-Impressionists (1910–11) and the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition (1912).

Venues dedicated to other entertainments could also be converted to Kunsthalle, as in the case of the Royal Albert Hall, which hosted the Allied Artists’ Association, an artists’ exhibiting society founded by Frank Rutter in 1908, following the non-jury system of the French Société des Artistes Indépendants. The first AAA exhibition, in July 1908, included over 3,000 works. Until 1913 the Association’s six shows were all held at the Royal Albert Hall; because of its debts none were held in 1915. In the following year, the London Salon moved to the Grafton Galleries where the annual exhibitions were held until 1920.

The Allied Artists’ Association provided an important venue for many of the artists who would become the Camden Town Group. Artists paid an annual fee and in exchange could exhibit five (later three) works of art. The display was organised by a Hanging Committee, the membership of which rotated among the members in alphabetical order. These democratic principles were lauded by Sickert, who advocated that ‘for the purposes of this Association, there are no good pictures, and no bad pictures. There are only pictures by shareholders’, believing that ‘the consequences of the practical assertion of this principle ... will be of an importance that is incalculable’.20

Exhibition strategies

The uniqueness of the Allied Artists’ Association was that lack of a jury; most exhibitions had some sort of gatekeeper, whether a jury, curator, art dealer, or a dealer’s designated representative, as in the case of Sickert’s role in organising the London Impressionists exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in 1889.

The group show, long associated with artists’ exhibiting societies, persisted within the framework of the commercial art dealer, as Sickert’s project for Goupil indicates. Indeed, dealers often showed the works of societies, recognising that their cachet helped to legitimate their own practices and remove the possible taint of commercialism. The Goupil firm, when under the management of William Marchant, initiated the Goupil Salon, which featured many British modernist artists, its title falsely suggesting an artist-run enterprise.

In the early twentieth century, the strategy of the group exhibition took on a new twist in the wake of Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions. Recognising the significance of the critical attention that Fry’s shows had elicited, group exhibitions adopted stylistic labels, as opposed to simply referring to the name of the exhibiting group or using the generic label ‘Salon’. In 1912, for example, the Italian Futurists exhibited at the Sackville Gallery; in 1912 the Fauves showed at the Stafford Gallery; and, as already mentioned, in 1913, Rutter organised the Post-Impressionist and Futurist exhibition at the Doré Gallery.

Rising alongside this long-standing practice of group shows was the solo retrospective, which allowed the dealer to champion a single artist’s reputation, as the Goupil Gallery did for Whistler in 1892. Developing a relationship with a group of artists helped the dealer broker single-person exhibitions, which became increasingly prominent as the twentieth century progressed. For example, after the Camden Town Group exhibitions, Charles Ginner held a paired exhibition with Harold Gilman at Goupil in 1914 and then a solo exhibition there again in 1922.

The social geography of the turn-of-the century art trade

Sickert’s reference to shareholders in the context of the Allied Artists’ Association implies that he believed that the market was the best judge of quality. But, given that many commercial dealers, artists’ societies, and ad-hoc formations hosted by Kunsthalle frequently shared similar stock and stratagems, the means of marking distinction, such as geography and the physical disposition of the space, bore additional pressure.21

The areas of Old and New Bond Street and St James’s Square competed as the leading centres for the luxury art trade, followed by Pall Mall, the area around Regent and Oxford Street, Bloomsbury and Holborn, the Strand, Soho, and, lastly, the King’s Road and Fulham Road quarter. This geographic distribution largely reflects the dual legacy of the art trade as a product of print publishing, historically located in the Strand, and as a luxury commodity, akin to the goods proffered by jewellers and tailors located around St James’s. In addition, the art trade was shaped by the location of the Royal Academy, concentrating around New and Old Bond Street around the time that the institution moved to Burlington House in 1867. By contrast, in Paris, the art trade had historically situated itself near the stock exchange.

Old and New Bond Street were dotted with the leading firms, such as Thomas Agnew & Sons, Dowdeswell, the Fine Art Society and the Goupil Gallery. Goupil, in keeping with its emphasis on print selling, was initially on Southampton Street and then relocated, by 1884, to New Bond Street and subsequently Regent Street in 1893. Carfax likewise exploited the benefits of social geography, locating in the elite neighbourhood of St James’s Square.

But the Leicester Galleries, as their name suggests, ventured into relatively new territory for the art trade – Leicester Square. The Chenil, situated on King’s Road in Chelsea in a Georgian townhouse, was even further outside this constellation of wealth and social prestige, as was the Whitechapel Art Gallery, founded in 1901 and deliberately situated in the immigrant neighbourhoods of East London in accordance with its philanthropic goals.

Spaces and techniques of display

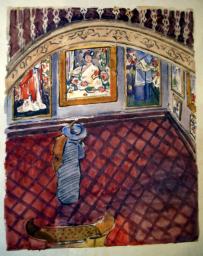

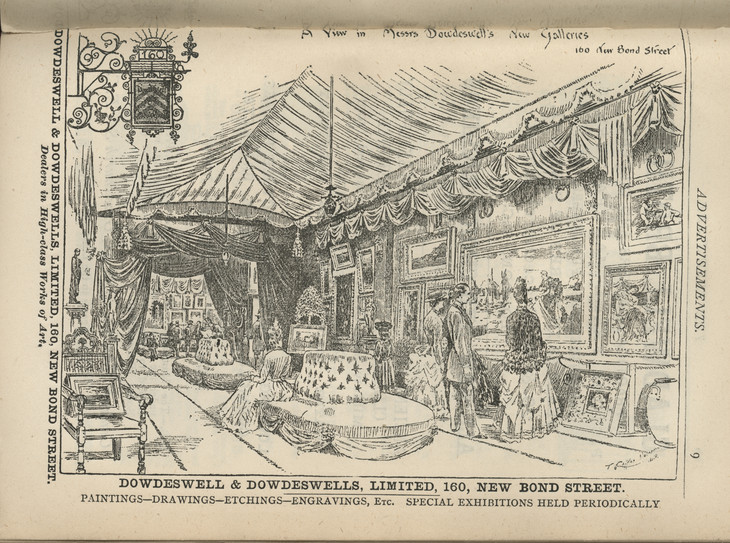

The rhetoric of wealth and prestige sought by major firms of the West End, such as Dowdeswell and Goupil (figs.4 and 5), was reaffirmed by their top-lit and luxuriously appointed picture galleries, which emulated those of wealthy aristocrats, a template that reached its climax with the Grosvenor Gallery. Its lavish appointments – top-lit gallery, carved architectural decorations, oriental carpets and dark walls – created an atmosphere of luxury and were deliberately contrasted later on by the relative austerity of the Chenil and Carfax.

Dowdeswell & Dowdeswells, Limited, 160, New Bond Street 1891 Year's Art

Fig.4

Dowdeswell & Dowdeswells, Limited, 160, New Bond Street 1891 Year's Art

Interior of the Goupil Gallery, London October 1927

Photograph, black and white, on paper, by A.C. Cooper, London

218 x 287 mm

Tate Archive TGA 8314/1/7/12

Fig.5

Interior of the Goupil Gallery, London October 1927

Tate Archive TGA 8314/1/7/12

While the address of the Carfax Gallery resonated with associations of the luxury trade, its physical location in Bury Street was markedly different: its rooms were small and those in the basement presumably lacked the top lighting of most galleries. Huntly Carter recalled, upon the occasion of Sickert’s solo show in 1912, that ‘the walls were a dirty gold’.22 Its small staff contrasted with the teams of clerks, managers and uniformed concierges that presided at such venues as Goupil.

Chenil’s bohemianism existed in a dialectical relationship with the plush spaces of the West End, often designed by architects, as in the case of the Fine Art Society and Thomas Agnew & Sons. Located in Chelsea, with its village-like atmosphere, the Chenil, as well as picture galleries, had spaces devoted to a printing press and for selling artists’ supplies, thereby conflating the artists’ working processes with the display of their work.

Fluidity and pluralism

Roger Fry, when he assumed the role as advisor to the Grafton Gallery, sought William Rothenstein’s advice in creating ‘a great nonacademic retrospective’ at the gallery, with an aim to make more visible ‘the younger and more vigorous artists’, recognising that exhibitions ‘remain the only possible medium of communication’.23 The need to consolidate the work of this generation was particularly acute given the diverse exhibiting venues that existed at this time and artists’ tendency to use as many of these as possible. Sickert, like Fry, recognised that with respect to the group of artists affiliated with Fitzroy Street and Camden Town a unity of effort might result in greater visibility. Indeed, Sickert, like his mentor Whistler, was particularly adroit in negotiating the social topography of London’s art market, exhibiting with both artists’ societies and a broad range of commercial dealers, including Goupil, Carfax and the Leicester Galleries.

Context and conclusion

The Camden Town Group, in choosing Carfax, acknowledged the significance of cultural geography and the ready-made social and critical network associated with this venue. To make this point, consider that much closer to their former Fitzroy Street home was the department store Maple & Co. at 141–150 Tottenham Court Road, one of many high-end department stores at the time that were beginning to expand into the fine-art trade, but whose explicitly commercial associations, lack of exclusivity, and absence of critical approbation were entirely inappropriate to the Camden Town Group project.

The Group’s strategy of a collective exhibition was a venerated tactic that reveals the resilience and, indeed, necessity of this mode of display, despite the rise of the solo show and retrospective within the framework of the commercial art dealer. The choice of the Carfax was shaped by such decisive factors as geography, display technologies, representative stock and management. Yet, while the Carfax, like other commercial art dealers, strove for a reputation of singularity and distinction, its business was dependent on the concentration of other art dealers, Kunsthalle, artists and critics that existed in London’s West End, creating networks of production, consumption and reception as well as codes and values associated with various loci or nodes within this constantly changing network.

These configurations, however, dramatically changed in the interwar period, following the volatility of the art market in the wake of the Great War and the marked economic depression of the late 1920s. Some spaces were unable to survive; the Doré Gallery, for example, had already closed in 1914. Others were driven away from the West End owing to the rising costs of rent. Chenil found that it faced increasing competition in Chelsea and, despite an ambitious renovation scheme, was unable to adjust to the changing conditions of the interwar period. New strategies, such as affiliating fine art with the decorative arts, arose and were capitalised upon successfully by department stores, such as Heal’s, which opened its own exhibition space, the Mansard Gallery.24 Nonetheless, pluralism continued to mark the British art market, albeit characterised by a newly configured social-geography and exhibition strategies shaped by a new modernist aesthetic.

Notes

For an introduction to the range of Whistler’s activities, see Philip Athill, ‘The International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers’, Burlington Magazine, vol.127, no.982, January 1985, pp.21–9, 33; Martin Hopkinson, ‘Whistler’s “Company of the Butterfly”’, Burlington Magazine, vol.136, no.1099, October 1994, pp.700–4; and Patricia de Montfort, ‘Negotiating a Reputation: Whistler, Rossetti and the Art Market, 1860–1900’, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (eds.), The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2012.

The material for this essay stems largely from research conducted for Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (eds.), The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2012.

David H. Solkin, ‘“This Great Mart of Genius”: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836’, in David H. Solkin (ed.), Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2001, p.5.

These artist-run societies or exhibiting societies supported a diversity of processes (for example sketching clubs), media (such as engraving, pastel, tempera, watercolour), and other forms of affiliation (for example, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, the Society of Women Artists, the International Society of Sculptors, Painters, and Gravers, and the New English Art Club).

Walter Sickert, ‘Transvaluations’, New Age, 14 May 1914, p.35, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.365.

Pamela Fletcher has explained these factors in relation to one of the early leaders in the field, Ernest Gambart, in ‘Creating the French Gallery: Ernest Gambart and the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in Mid-Victorian London’, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol.6, no.1, Spring 2007, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=143:creating-the-french-gallery-ernest-gambart-and-the-rise-of-the-commercial-art-gallery-in-mid-victorian-london&catid=46:spring07article&Itemid=68 , accessed 15 February 2010. For more on artists’ suppliers from 1650 to 1950, see the database developed by the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/w.php , accessed 15 February 2010.

Huntly Carter, ‘Letters from Abroad. I. – The New Idea of Dramatic Action’, New Age, 20 July 1911, p.272.

Youssef Cassis, ‘Introduction: Comparative Perspectives on London and Paris as International Financial Centres in the Twentieth Century’, in Youssef Cassis and Éric Bussière (eds.), London and Paris as International Financial Centres in the Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p.2.

Malcolm Gee, Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting: Aspects of the Parisian Art Market between 1910 and 1930, Garland Publishing, New York 1981, p.37.

For more on the Paris firm, see Gérôme & Goupil: Art and Enterprise, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 2000.

See Samuel Shaw, ‘The Carfax Gallery and the Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/samuel-shaw-the-carfax-gallery-and-the-camden-town-group-r1104371, accessed 21 August 2013.

A full listing of the Leicester Galleries’ exhibitions from 1902 to 1977 can be found at http://www.ernestbrownandphillips.ltd.uk/Static/general.html , accessed 20 February 2010.

For more on the Chenil Gallery, see Anne Helmreich and Ysanne Holt, ‘Marketing Bohemia: The Chenil Gallery in Chelsea, 1905–1926’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.33, no.1, March 2010, pp.43–61.

Memorandum and Articles of Association of the Grafton Galleries, 16 June 1891, Tate Archive TGA 737/1.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Allied Artists’ Association’, Art News, 24 March 1910, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.207.

To this list one could add the persona of the dealers, but space does not permit discussion of the various managers here.

Roger Fry, letters to William Rothenstein, 4 August 1905 and 28 March 1911, Sir William Rothenstein Correspondence and Other Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS Eng 1148.

For more on these new strategies, see Andrew Stephenson, ‘“Strategies of Situation”: British Modernism and the Slump, c.1929–1934’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.14, no.2, 1991, pp.30–51. See also, Andrew Stephenson, ‘Strategies of Display and Modes of Consumption in London Art Galleries in the Inter-War Years’, in Fletcher and Helmreich (eds.) 2012.

Anne Helmreich was Associate Professor of Art History and Director of the Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities at Case Western Reserve University and is currently Senior Program Officer, Getty Foundation

How to cite

Anne Helmreich, ‘The Socio-Geography of Art Dealers and Commercial Galleries in Early Twentieth-Century London’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www