Walter Sickert: Art Critic for the New Age

Anna Gruetzner Robins

Walter Sickert believed that the best writing on art was informed by knowledge of a work’s nature and materials. Focusing on Sickert’s articles for the New Age written between 1910 and 1914, Anna Gruetzner Robins explores his legacy as an art writer.

Walter Sickert started the year 1910 with a burst of art criticism. Between January and June he wrote a weekly column for the Art News, together with another weekly column for the New Age that appeared between April and September.1 He then more or less ceased writing for the latter journal until beginning another six-month stint in January 1914. This period of high productivity followed by a more fallow one follows a pattern he established in the 1880s when his taking up of the pen first marked a new moment in his artistic practice. His writings in the New York Herald (London edition) in the first part of 1889 were written the same year that he launched his own impressionist group, ‘The London Impressionists’, which in many ways was a blueprint for the later Camden Town Group. Like other late Victorian art critics, Sickert wrote about the established London exhibition circuit, including the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition; but he felt no obligation to pay lip service to the Victorian convention of listing as many pictures as possible in one review. Instead, he chose examples to illustrate his own polemic, and often exercised what even in his youth (he was twenty-nine) was a withering witty comment when a picture did not come up to standard. As they gained success at the Royal Academy, the Newlyn painters Frank Bramley and Stanhope Forbes were a particular target; yet at the same time he was full of admiration for the pictures of Frederic Leighton, the president of the Royal Academy. Often a review of an exhibition was a pretext for setting out his own ideas about art-making and the excuse to praise some of the artists he knew the best and most admired, such as Edgar Degas and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Even then, an expert use of painting and drawing techniques was a priority for him. Sickert’s early writings represent a new type of art criticism, also practised by critics such as D.S. MacColl, George Moore and Elizabeth Pennell, who turned the ‘New Art Criticism’, as it came to be known, into an influential form of art writing in London in the 1890s.

The New Age: An Independent Socialist Review of Politics, Literature and Art was a perfect conduit for Sickert’s love of high and low culture. Its editor, A.R. Orage, believed that all aspects of culture could provide the solution to social problems. The contributors, including H.G. Wells, Katherine Mansfield, T.E. Hulme and Ezra Pound, attended Orage’s weekly editorial meetings in the ABC restaurant, a tea room on Chancery Lane in the heart of London, where Orage encouraged heated debate about current political, social, economic and cultural topics. Often their war of words would continue onto the pages of the New Age.

Sickert’s articles in the New Age encompass his Camden Town period and are a useful source of information about this phase of his long career. They reveal an increasingly complex modernist strategy as he came to terms with a vibrant period in British art between 1910 and 1914. The Camden Town Group was officially inaugurated in 1911 when it held two exhibitions in June and December followed by a third in December 1912. The group is as well known for its innovative, artist-organised exhibitions of small-scale work as it is for its mesmerising images of modern-day London. Sickert set out the rationale behind these small, artist-managed exhibitions, which he saw as countering the extravagant opulence of Edwardian society and its love of what he considered large, ‘bad-taste’ pictures that juggled for attention in the highly commercial marketplace of the Royal Academy. The impressionist exhibitions were an early model for the Camden Town Group shows because they ‘killed ... the exhibition picture and the exhibition system’ and introduced ‘the group system into exhibition rooms, showing that one picture by an artist ... forms a link in a chain of thought and intention that runs through his whole oeuvre’.2 The small scale of impressionist painting, ‘suitable to the rooms we live in, and to the growing mass of customers of moderate means’, was a second influence on Camden Town painting, while the close cooperation of dealers who were willing to forego enormous profit margins was a third.3

As Sickert acknowledged, the impressionists extended the range of modern subject matter, painted natural light and shadow as colour, and adapted traditional methods of drawing to a new way of making art. Camden Town painting emulated this model but had its own artistic programme, including the painting of the female nude in ordinary London settings. These nudes, one of the mainstays of Camden Town painting, met with the heavy weight of moral disapproval from the London art establishment. Characteristically, Sickert used wit as a weapon to cut through the stifling hypocrisy and complacency of public opinion. ‘If we venture to exhibit a painting of a plump and wholesome woman in her bath ... we are told we are lewd fellows, and no class,’ he wrote, while those ‘who paint boys bathing have to give nine-tenths of their attention to an ingenious game of thimble-rig with a ridiculous and necessary organ.’4 The enduring greatness of Sickert’s Camden Town painting was the many studies of the figure clothed and unclothed in the dimly lit interior of an ordinary London room. His description of the ‘afternoon light’ flowing through ‘the open folding doors, from the small back-room’ onto a man who is ‘saying ... some of those nothings that we willingly listen to’ while the light ‘carved him like a gem’, making his ‘image the quintessential embodiment of life’, serves as a manifesto for the painting of the interior by the Camden Town Group.5

As a practising artist, Sickert believed that the best writing on art was written with knowledge of an artwork’s ‘material and its nature, outwards to its resulting message’.6 Skill and respect for the characteristics of each technique and medium, whether it be drawing , print-making or painting, ensured that a work of art shared a ‘language of art’; as Sickert explained in an impassioned plea, ‘the real subject of a picture or a drawing’ is what he called ‘the plastic facts’.7 This language of art transcended national schools and what Sickert considered to be the fashionable concept of the avant-garde, which explains why he could admire the drawings of the Royal Academician Edward Poynter as well as those by Degas. Drawing was at the heart of Sickert’s artistic agenda and some of his best writing on the subject was published in the New Age.8 A drawing was an ‘extraction from nature’ and should be in proportion to the scale of vision, but its linearity made up a ‘language of design’ which had its own visual expressiveness.9

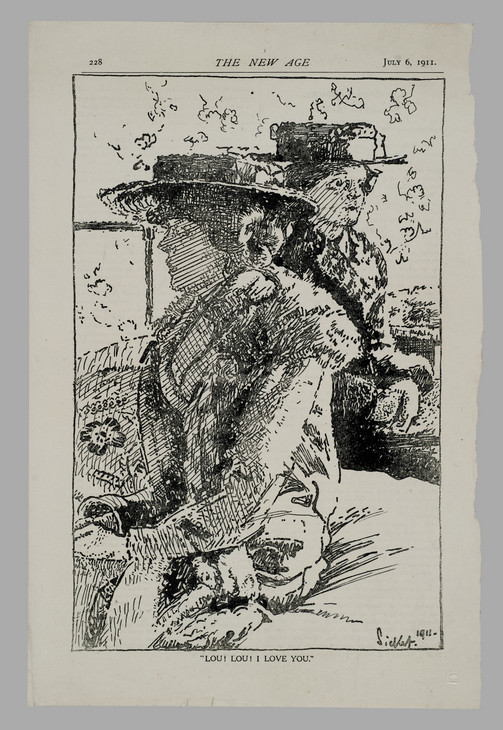

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Lou! Lou! I Love You 1911

Lithograph on paper

332 x 220 mm

Inscribed by the artist 'Sickert. 1911.' bottom right

Tate Archive TGA 8120/3/49

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Lou! Lou! I Love You 1911

Tate Archive TGA 8120/3/49

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Sickert could not have anticipated that the programme of picture-making that he set out in the first part of 1910 would be turned on its head at the end of that year when Manet and the Post-Impressionists, the first of Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions, opened in London. Many of the young painters in his Camden Town Group, including the much-revered Spencer Gore, took up what can be loosely described as a post-impressionist style that drew on the work of Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Matisse and other artists represented in Fry’s shows. Sickert’s tribute to Gore, who died prematurely in 1914, reads like a eulogy to a beloved son whose wayward ways can be overlooked because his lineage can be traced back to the father’s own practice.11 A month later, however, he was willing to hand over the mantle and agree that Gore’s ‘assimilation of Cézanne’ made him an influential modern artist.12 His real anxiety about the wave of post-impressionist influences sweeping through the London art world is revealed in the New Age article ‘Mesopotamia-Cézanne’, which was ostensibly a review of Clive Bell’s Art (1914), but also an opportunity to use the bag of tricks he relied on – writing in several languages, and using slang, ditties and references to the classics and popular culture – to detract from his dismissal of something of which he did not thoroughly approve.13

By 1914 Orage had persuaded some of the most radical modernists in the London art world, including T.E. Hulme, Wyndham Lewis and Pound, to join his list of illustrious contributors. In March of that year, Sickert attacked Hulme’s ‘incomprehensible bedevilments and obfuscations and convolutions’, and Jacob Epstein’s sculpted ‘Pigeons’ which he considered to be pornographic.14 Then Hulme had his turn. The intense debate, which Orage encouraged, became a war of drawings rather than words when Orage asked Hulme to select ‘Contemporary Drawings’ to be presented in the periodical as a more daring alternative to Sickert’s ‘Modern Drawing’ series, which first appeared in January 1914 and included works by Sickert, other Camden Town artists and associates, and his pupils.15 Introducing his series in April 1914 with a drawing by David Bomberg, Hulme pointed out that ‘you will have ... the advantage of comparing the drawings with the not very exhilarating work of the more traditional school ... in the series Mr. Sickert is editing’.16 Next Sickert’s art criticism came under attack from ‘Arifiglio’, who was almost certainly Pound, who unjustly derided Sickert’s writing as a load of nonsense in two attacks written in a cruel parody of the artist’s unique style.17 As a result, Sickert ceased writing for the New Age and instead made use of his skills in the more establishment journals. Sickert’s writings on art consistently stress the interconnection between modern subjects and new methods of making. An equal emphasis on the meaning and the method behind a work of art is part of his legacy to the study of modern art.

Notes

For Sickert’s art criticism, see Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, which reproduces his art criticism in full with annotations.

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, New Age, 30 June 1910, p.205, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.254. The New Age has been digitised as part of The Modernist Journals Project, http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/ .

For more on the importance of drawing to Sickert’s practice, see Alistair Smith, ‘Walter Sickert’s Drawing Practice and the Camden Town Ethos’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/alistair-smith-walter-sickerts-drawing-practice-and-the-camden-town-ethos-r1104369 , accessed 21 August 2013.

Walter Sickert, ‘Mesopotamia-Cézanne’, New Age, 5 March 1914, pp.569–70, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.338–42.

The drawings, apart from the first (a drawing of Enid Bagnold by Sickert), were published as a numbered group, and, interestingly, Sickert styled himself as editor of this pictorial series. For example, Charles Ginner’s Leicester Square had the subtitle ‘Modern Drawings – 4 Edited by Walter Sickert’ (New Age, 22 January 1914, p.369).

Anna Gruetzner Robins is Professor of History of Art at the University of Reading.

How to cite

Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘Walter Sickert: Art Critic for the New Age’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www