Sigmar Polke is a brilliantly witty artist. I use the word ‘wit’ in the way it was used of English 17th-century poetry, to describe a ranging and probing intelligence that investigates everything, connecting disparate images and ideas. He can be flatly comic and slapstick. He can equally make layered and ambiguous images of great subtlety. He does not preach or hector; I have the sense that he expects his audience to participate in the rueful irony – and in the delight – with which he presents his phantasmagoria. He has constructed, arguably, the most complete language I know for describing modern reality.

He began in the 1960s as a member of the group of German ‘Capitalist Realists’ opposed both to East German Socialist Realism and to American Pop’s glossy celebration of modern materials. Polke’s early works show a fascination, which is both deadpan and bizarrely exotic, with the objects and textures found in petit-bourgeois living-rooms. He painted, typically, three solitary socks, or a group of pastel-coloured plastic bowls of various forms – which nevertheless make one think (uncomfortably) of Cézanne’s primal cube, pyramid and cylinder. He painted the banal motifs of furnishing fabrics – palm trees, leopard spots, snowdrops, flamingos – not primarily to sneer, but to show nakedly those emotions to which they aspired in their flatness. He knows that we live, like no previous culture, in a swarm of insistent man-made visual images – and he is more interested than repelled.

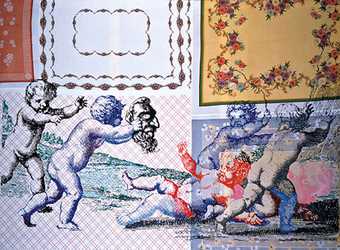

Sigmar Polke

Putti Playing with a Mask 2002

Mixed media on fabric, 223 x 303 cm

Collection of Matthew and Iris Strauss, Rancho Santa Fe, California © Sigmar Polke

He also painted ‘German’ things: sausages, potatoes, unromantic, stodgy foods. And he elaborated on them. A string of sausages becomes a kind of German demon prancing into a lipsticked advertisement mouth. He made stolid installations of potato racks. He made potato-head pictures. In an essay presented as a collaboration with the psychologist Friedrich Heubach, he writes about potatoes like a benign Surrealist. He says he was making a ‘scientific investigation’ of the source of art and – ‘having thoroughly explored the classical prescientific problem-solving models such as transpiration (99%) (Goethe) rotten apples (Schiller) reading the civil code (Stendhal) promiscuity (Maupassant) and so on in vain…’ – he decided to investigate the potato.

Of course – if there is anything at all that embodies every aspect of the artist that has ever come under discussion – love of innovation, creativity, spontaneity, creation completely from within oneself etc – it is the potato. One need only watch as it lies in a dark cellar and begins to sprout spontaneously, innovating sprout by sprout in a virtual torrent of creativity; and then as it disappears beneath its teeming sprouts – retreating totally behind its work – and brings forth the most amazing forms. And what colours! The practically shivering frozen lilac in the tips of its sprouts, the spaceless pale white of the sprouts themselves, with an occasional hint of morose, earthless green – and finally the timeless, maternal wrinkled brown of the self-consuming fruit that sacrifices itself entirely in the perfection of its work.

These phantom colours in prosaic potato sprouts lead to the consideration of Polke’s own wildly sprouting innovations in the form, texture and surfaces of his pictures. He questions the very idea of a painting as a layer of pigment on canvas, either as a perspectival ‘window’ on a represented visual reality, or as an abstract patterning of colour and form. I do not feel that he does this out of any simple subversive desire to reject or discard earlier visual forms – indeed, one of the delights of his work is its constant dialogue with the past, from medieval Germany to 18th-century France, from Constructivism to Matisse. He is an explorer and a discoverer, eclectic and inclusive.

In his youth he trained as a worker in stained glass, and this has contributed to his interest in transparency and translucency. This can appear to be a rigorous exposure of illusion, when he uses transparent lacquers and artificial resins through which the stretchers of his canvas can be clearly seen. This rigour is related to his use of the rasters, dotted patterns, which form printed representations of photographs. These he reproduced painstakingly by hand, relating them to ‘polka dot’ patterns on fabrics, and by extension to seeds and peas.

He introduces all sorts of framing devices – lenses and apertures, gun-sights, bomb-sights, surveillance cameras He works with photocopiers, or deliberately distorted and baffled photographic processes.

But what he is studying is the irrepressible inventiveness of the individual eye and mind He collects printing errors which can produce monsters like those which spring from Goya’s Sleep of Reason, can make swimming silvery phantoms from slick fashion photos, or alchemical transmutations from massproduced comic strips. He uses all sorts of stable and unstable pigments – photographers’ silvers and platinums, raw minerals, water-absorbing paint that changes colour as the day heats up, so that his work is always a dialogue between a temporary order and disorder, or new formal invention breaking through. He is interested in sudden visions in blurred ink or spilled milk, as Constable was interested in clouds and Leonardo in cracks in the walls. His very beautiful coloured Apparizione are falls and slicks and trails of crimsons and scarlets and creams and cloudy whites, in which we are deliberately beckoned to see the phantasmagoria of Goethe’s Brocken, rather than being required to see that colour is a thing in itself.

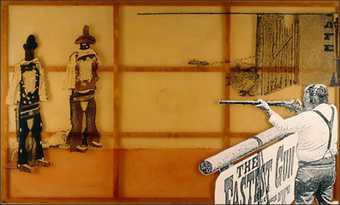

Sigmar Polke

Anyone Can Have Out-of-Body Experiences at Will 2002

Mixed media on fabric, 302 X 403 cm

Courtesy Michael Werner, New York and Cologne © Sigmar Polke

His work is a study of its own possibilities and nature, but it would not be so clearly great work if that were all it is. He is a subtle historical painter and a wisely mocking political observer. His series of paintings of Hochsitze (watchtowers – literally ‘high seats’) are based on the doubleness in German eyes of the woodman’s or hunter’s lookout in the profound German forest, and the surveillance post of the guard in a concentration camp, or along the border of a divided Germany. They shimmer with silver oxide and silver bromide like loomings in the mist. They have barbed wire made of striped pyjama material, or are painted luridly onto jolly black fabric with sunglasses and umbrellas, surrounded by mild outlined fairytale geese, dreams of German childhood.

His wicked and multifarious series of works on the anniversary of the French Revolution uses old French prints of great moments – the march to Versailles, the singing of the Marseillaise – to underline horror and pathos with elegance. Three very dead heads on pikes reach triangularly for the sky, dwarfing the triangular spire of a church, and are labelled ‘Libert, Egalit, Fraternit’. Childsplay shows two solemn 18th-century children playing in a prettily coloured meadow. Their ball is a severed head. A very jolly collection of souvenir wrapping papers from the 1980s takes the vague form of a guillotine – and turns out to be a real objet trouvé from a French catalogue.

An underlying preoccupation, it appears, is the possibility of nuclear war, with its blinding flash and consequent nuclear winter. Frau Herbst und seine zwei Töchter reproduces an atmospheric fairy-tale print by Grandville (1803–1847) of the old lady in the clouds shredding feathers of snow on a wintry landscape – but to the right of the picture is a blindingly glistening stretch of one of Polke’s dangerous formless white slicks, dwarfing a tiny mountain.

Das Problem Europa, Sargdeckel (coffin-lid) starts with a newspaper photograph, reproduced on a fabric patterned with grey squares on drab white, of Ronald Reagan smiling at a small caricature manikin he has drawn. The work consists of five images. In the second the raster has degenerated into slithering black fragments like floating ash. In the third the forms have become glowing crimson and represent a map of contained conflagration, flowing into formlessness.

The work was painted when America was discussing the possibility of a ‘contained’ European nuclear war, with the new neutron bomb. In the fourth element a small golden Europa is carried away on a tiny bull, while above her is a candle on khaki chevrons and a naked black footprint – which reminds me of the fact that the heat at Hiroshima left imprinted shadows of vanished humans. The fifth element is coffin-shaped, earth-brown, blotched with swirls of cloud and green not-quite swastikas.

I want to end by discussing two works – both multi-layered and both very European – the Laterna Magica (magic lantern) and Paganini.

The Laterna Magica 1988–96 is modern in that it is an installation, a grouping of transparent screens painted on both sides, inside and outside which spectators can walk. It is ancient in that it recreates the flickering transparent surfaces of the first projected images. Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust, and in the earlier Faust books, is a showman who produces Helen of Troy with a light-box and puppets. Wandering players used it to present the lively flaming of the Mouth of Hell. It is a world of candles, and later of limelight, and later of early cinema cartoons. It is an eclectic mix of the creatures that haunt our history and the caverns of our heads. A cartoon newspaper reader finds himself on the other side of his screen lined up in the sights of a rifle. A thumbprint becomes a monster. Two mechanical monkeys seesaw and smile. The story of Mother Hubbard and her dog is acted out in such two-dimensional pretty silliness that it becomes sinister. Kings, knights and princes appear and disappear in transitory forests. People are seen being recreated in alchemical retorts. A small boy in a cartoon spaceship explodes our planet and tries to stitch it together like a soft ball. Philipp Otto Runge’s (1777–1810) colour pools appear, as do Albrecht Dürer’s (1471–1528) perspectives. A wonderful decorative lion from a set of goldsmiths’ designs cavorts and prances. Two of Grandville’s anthropomorphic lizards, lounging and smoking by a ruin, are metamorphosed on the reverse of their screen to mechanical Transformers, toy robots which change shape and function.

Paganini 1982 is an acrylic painting on fabric. Its central scene is a reworking of an engraving by David Bailly (1584–1657) where an energetic devil plays the violin to a dying (or sleeping) man. Critics have tried to identify the recumbent figure with Paganini, who was said to play so brilliantly because he had a Faustian pact with a devil. They have also tried to identify him with Goethe on his deathbed. (Andy Warhol was working on images of Goethe at the time.) To the left of the painting a jester – at first sight jolly, at second sight blinded and eyeless, or made of cloth – juggles spools of tape, which become symbols of nuclear hazard, which become death’s-heads, flying round in a blue and white vortex of light. Below them is a group of the characterless 1950s advertising housewives and tradesmen of Polke’s earliest vocabulary. Between devil and dying man a dark door opens transparently onto starry emptiness. Around the demon twirls a golden band that is his song, or a serpent with feet.

Never was a painting so ingeniously or so superabundantly infested with swastikas. The landscape-checkered cloth of the background has been drawn on to shape the fields into hooked crosses. The rosary of the dying man is composed of them. Some of the banal two-dimensional people have potato-heads with swastikas for features. They dangle from the devil’s horns on tassels. It is all bright and gay, with the rhythm of a dance, and terrible.

Paganini is a painting about Germany – not only about the presence of the past, but about the threat of the nuclear future. Its structure is surely a dialogue with Paul Celan’s (1920–1970) great poem Todesfuge (‘Death’s Fugue’) with its terrible, compulsive fiddling jig of a rhythm. ‘Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland. Death is a maestro from Germany.’

In Celan’s poem, the diabolical Master drives the speakers to dig themselves a grave in the sky – surely the transparent grey box full of stars in the paintings. Der Tod in the poem plays in the house with serpents. A serpent rears up behind the recumbent man’s bedstead. The seductive ribbon of gold light is a serpent or dragon, and it is connected to the spinning wheel of skulls and sky. I think Goethe’s death-bed is also present here. He is said to have asked for ‘more light’. The light that is being played into being by devil and jester in this energetic painting is the light that left the human shadows at Hiroshima. It is painted, in its turn, by ein Meister aus Deutschland.

Sigmar Polke Biography

Born 1941

Article provided by Grove Art Online

German painter. In 1963 Polke launched Capitalist Realism in response to Pop art, exhibiting the first works in this genre in Düsseldorf. Polke took as his motifs such ordinary food items as chocolate, sausages or biscuits, isolating them and apparently depriving them of their tactility in order to elevate them to the status of aesthetic signs.

Such Pop-related images, pictured in various combinations and in a number of techniques, became from this time standard elements of Polke’s work. The scattered dots in more complex works form a virtually abstract pattern that makes the imagery almost invisible when viewed from near the surface. Graphic alterations help to increase this sense of unfamiliarity, blurring the boundary between the objective reproduction of reality and the subjective production of art.

A different process was used for the Fabric Pictures. In these Polke used printed fabrics, which in their triviality reveal the tastelessness of everyday life, as background patterns for gestures and motifs drawn from earlier art and especially from mainstream modernism. Irreconcilable images are brought together. He continued to appropriate images and techniques from other artists and found materials.

In other paintings Polke introduced another variation of his attack on conventional ideas about individuality and innate creativity by altering the lines of his own palm.

Polke’s love of experiment, of abrupt stylistic changes and of contradiction, irony and mocking distance thus remained essential to his uncategorisable and innovative art.

Bibliography

Sigmar Polke: Original und Faelschung (exh. cat. by D. Stemmier, Bonn, Städt. Kstmus., 1974)

Sigmar Polke: Bilder, Tücher, Objekte: Werkauswahl, 1962–1971 (exh. cat., ed. B. H. D. Buchloch; Tübingen, Ksthalle; Düsseldorf, Ksthalle; Eindhoven, Stedel. Van Abbemus.; 1976)

K. Honnef: ‘Malerei als Abenteuer oder Kunst und Leben. Bemerkungen zum künstlerischen Werk Sigmar Polkes im Polke-Jahr’, Kstforum Int., lxxi-ii (1984), April/May, pp. 132–207

Sigmar Polke (exh. cat. by W. Beeren, S. Polke, D. Stemmler and H. Lieberknecht, Rotterdam, Boymans–van Beuningen, 1983; Bonn, Städt. Kstmus., 1984)

Sigmar Polke (exh. cat., ed. H. Szeeman and T. Stooss; Zurich, Ksthaus, 1984)

J. Gachnang, ed.: Sigmar Polke: Zeichnungen, 1963–9 (Bern, 1987)

Sigmar Polke: Zeichnungen, Aquarelle, Skizzenbücher, 1962–88 (exh. cat., Bonn, Städt. Kstmus., 1988)

Sigmar Polke: Photographien (exh. cat., Baden-Baden, Staatl. Ksthalle, 1990)