In 1949, British artist Ithell Colquhoun arrived in Lamorna.

A small village on the edge of England, known for fishing, granite quarries, and as a magnet for artists.

Drawn by the cliffs, coves, and Celtic standing stones of West Cornwall, she soon discovered the area's lesser known charms.

Colquhoun wrote:

Miss Moss and Mme Nyhoff lived together. Miss Moss had long ago had a relationship with Miss Palmer, who lived with Mrs Dodd. Miss P had also had a relationship with Miss Gluck. Mme Nyhoff went to Holland; Miss Moss had an affair with a mutual friend of theirs who lived in a caravan at Trecastle ... [they] wanted this to be permanent but Moss turned her down. Moss suggested living with Janet but Janet turned her down. Mme Nyhoff came back.

Colquhoun’s chronicle of queer relationships seems to be written with the voice of an outsider looking in.

Yet she once wrote about her love for a woman carrying her, in swirling torrents, towards ‘the lesbian shore’.

Was it these same torrents that brought her to West Cornwall? And into an avant-garde, queer network thriving on these wild shores?

This is the story of Lamorna Cove, the heart of queer Cornwall, and three artists who lived and loved there.

British painter and sculptor Marlow Moss came to Lamorna in 1941 with their partner, writer Netty Nijhoff.

As a Jewish and queer person in the early years of the Second World War, Moss fled to Cornwall from France after over a decade working in continental Europe.

They lived on and off in Lamorna until their death in 1958, when Moss’s ashes were scattered in the cove.

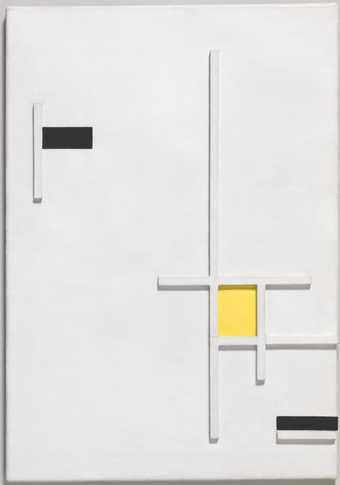

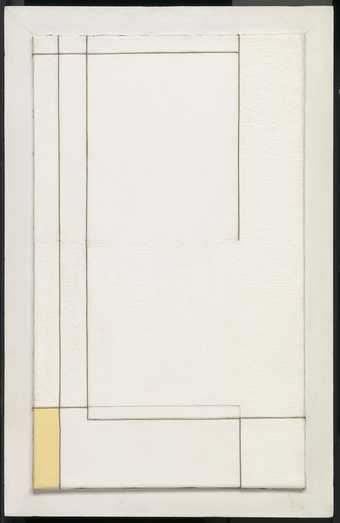

Moss’s work is abstract, bold, difficult, totally modern.

Unfortunately, art history tends to place Moss in the shadow of Piet Mondrian, even though Moss actually influenced his work on at least one occasion.

He was shocked by the way Moss introduced double lines to their abstract canvases. Moss told Mondrian that a single line grid was “a conclusion and a restriction”.

"I am no painter, I don't see form, I only see space, movement and light."

This sums up Moss’s approach to life.

Their arrival in Lamorna introduced the locals to a bold new look - on and off the canvas.

Moss abandoned a feminine birth name around 1920 and adopted the gender-neutral ‘Marlow’.

From their thirties until their death, Marlow presented in masculine – and rather dramatic - attire.

Their sophisticated tailoring, riding crops and a short back and sides challenged gender norms.

"I destroyed my old personality and created a new one".

This transformation was totally queer, and totally modernist.

And it was their (uncompromising,) authentic approach that made Moss’s life in Lamorna… bittersweet.

"I am very much alone in my ideas here. I have seen Ben Nicholson just once, things aren’t going well between us, I don’t even know why, so I never see him".

For reasons we can only guess, Moss’s invitations to tea and overtures of friendship to artists Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth in the nearby modernist haven of St Ives went largely unanswered.

Moss was a generous neighbour, who would give all the village children sweets at Christmas.

But the kids also spied on Moss while they were swimming, trying to work out their sex. Their butch presentation was radically brave, at the time, and even today. Telling Moss’s story asks us to consider our concepts of gender, and how we perceive queer icons of the past.

While Moss may well have been happy being described with the binary pronouns of their time, we can never be sure. Neutral pronouns are often used when referring to them - an option which honours all possibilities, and draws no conclusions.

After all, it was Moss who said that "Art is - as life - forever in the state of Becoming".

A sentiment no doubt shared by their neighbour and fellow queer trailblazer - the artist exclusively known as Gluck.

"I am flourishing in a new garb. Intensely exciting. Everybody likes it… I hope you will like it because I intend to wear that sort of thing always."

Gluck – a one word name, "with no suffixes, no prefixes, no quotes".

In 1916, Gluck travelled to Lamorna with their friend, fellow artist and possibly their lover, Craig – another self-chosen, single word name free from the constraints of gender.

Gluck’s mother, none-too-happy with these developments, called Craig "a pernicious influence", and labelled the artist’s infatuation with each other as "a kink in the brain".

As recent graduates eager for new experience, Gluck and Craig’s arrival in Lamorna’s artist colony must have been a life-changing adventure – and world away from the (uptight) high-society dinner parties of their youth.

The iconic painting Medallion, Gluck’s self-portrait with Nesta Obermer, is a rare example of the artist with a female lover. Traditional in style, radical in its representation. A striking yet intimate portrait of a couple, of queer figures in love.

If art and life are intertwined in Moss’s work, art and love are constant companions in Gluck’s.

Upper-class, wealthy, and business-minded, Gluck invented and patented their own bespoke frame, won a decade-long legal battle that reformed the accepted standards for oil paints, and challenged another artist's use of the name ‘Glück’, with an umlaut.

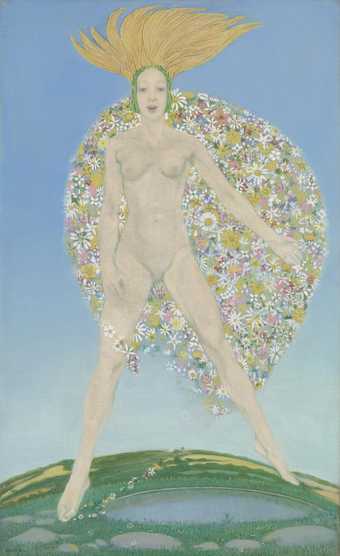

Gluck said that their paintings of the Cornish countryside were, "The first that truthfully showed the immediate impression one gets there – that of very little land and great expanses of sky".

Flora’s Cloak is an empowering depiction of a woman set in this great expanse... the Cornish landscape transformed into a magical and mythical space.

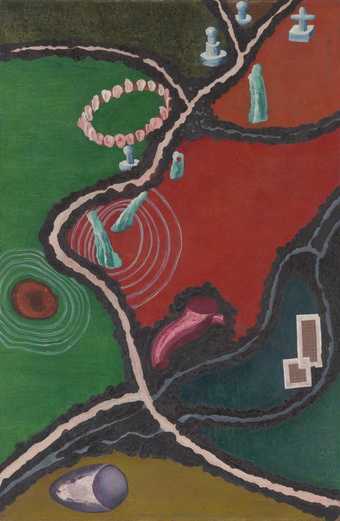

The sea, cliffs, coves and sky of Lamorna were a mysterious, psychic space, as well as a physical landscape, for Gluck – but also for our final subject, Ithell Colquhoun...

"Here, to exist is enough; one scarcely needs diversion, for the slightest happenings seem full of a crazy zest"

By the time Ithell Colquhoun moved to Lamorna she had already lived in Paris, travelled through Greece, Tenerife, and Corsica, and had split from both her husband and from the British Surrealists.

She was heavily influenced by their style throughout her career, but the strict rules of the surrealist movement jarred with Colquhoun’s interest in the Occult, and she was pushed out because of it.

Colquhoun lived a rather solitary life in Lamorna.

She rented a ramshackle hut with no modern facilities which she named Vow Cave.

This became her home and studio; and Lamorna Valley, her inspiration –

"Valley of streams and moon-leaves, wet scents and all that cries with the owl’s voice … Influences essences, presences, whatever is here … I share this place with you, ... for all you give me I offer thanks."

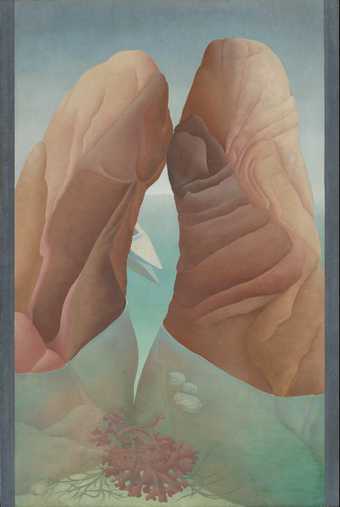

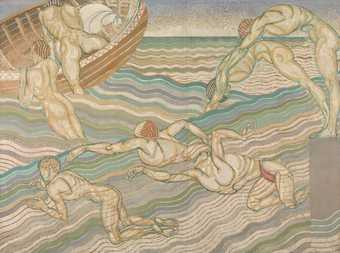

Colquhoun was fascinated by the Occult, Celtic mysticism and the mythical ‘Androgyne’ – a two-faced creature who existed at the beginning of creation, combining both male and female traits.

This mystical view of nature is laid bare in the painting Scylla. Figurative, but oddly dream-like, beautiful and androgynous, the viewer becomes the legendary Scylla herself, gazing through a pair of thighs - or perhaps a pair of narrow, phallic cliffs - at an oncoming ship.

Though she never publicly identified as lesbian, bi- or pan-sexual, Colquhoun wrote about sapphic desire for the Greek woman Andromaque Kazou :

"I did not try to analyse the stirrings within me, I could not reflect upon them while thus borne along. It was not until later and in calmer intervals, that I recognised this torrent that swirled me onwards … I was being carried, indeed, to the Lesbian Shore".

"If ever a country was 'pixielated…'" said Gluck "…it’s Cornwall."

Lamorna’s queer trailblazers held a love for Cornwall that was deep and enduring - if, perhaps, romanticised.

The freedom to live authentically in a rural village, while travelling often to London and Paris, was made possible by their financial resources.

As upper-middle class artists, Gluck, Moss and Colquhoun were afforded a social mobility rarely enjoyed by the local population - and a world away from the lives of their queer working-class neighbours.

It’s these queer Cornish voices – some named in the writings of Ithell Colquhoun - who are rarely documented. Who was Miss Palmer? Who was Janet?

Still, this drive to seek connection, community and re-invention outside of your birthplace and class structure is a queer rite of passage. Moss, Gluck and Colquhoun each found an opportunity to live truthfully and with greater privacy in Lamorna.

This small fishing village, not far from Land’s End, was their shared passion, inspiration and refuge.

Lamorna is a small village on the Cornish coast, in the far southwest of Britain. The expansive skies and landscapes of the area have long been a draw for artists, most famously painters associated with the Newlyn school such as Laura Knight, Alfred Munnings and Lamorna Birch.

Less well known are the ground-breaking queer artists who set down roots in the village: Marlow Moss, Gluck and Ithell Colquhoun.

In this film, we tell their story, and the story of the Cornwall where they lived and loved: a place of international modernism, Celtic spiritualism and the queer avant-garde.

A Note on Language

Telling the stories of these three artists asks us to consider our concepts of gender and sexuality, and how we perceive and represent queer figures of the past. The word ‘queer’ itself has a mixed history, used both as a term of abuse and as a term by LGBTQIA+ people to refer to themselves. In recent times, it has become reclaimed as a fluid term for people of different sexualities and gender identities. In this film, we use ‘queer’ in this broad and inclusive sense, rather than making specific assumptions about how these artists would choose to identify.