This painting is in oil on canvas measuring 1499 x 1270 mm (figs.1−4). The canvas support is composed of two pieces of identical, plain woven linen joined together at a stitched, vertical seam passing through the cheek of the boy (fig.5). The larger, right-hand section is 1020 mm wide and the left 233 mm. Both pieces have 10 threads per sq cm in each direction; it is an open weave with threads of uneven thickness. There are no tack-holes or cusping either side of the seam when it is viewed in the x-radiograph, which would confirm that the two pieces of canvas were present from the inception of the composition.1

The original tacking edges are present around the edges of the painting.

Fig.5

X-radiograph of Endymion Porter

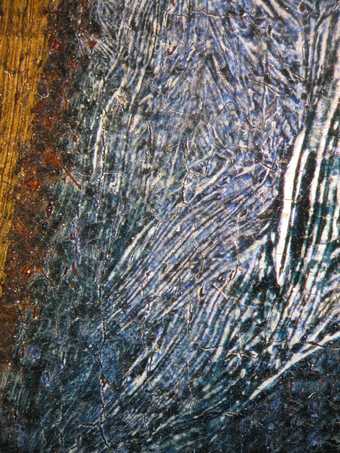

The ground is mid-grey colour and very thin. It sits in the hollows of the canvas weave with only the thinnest skim on top of the threads. It was noted during relining in 1970, when the back of the canvas was revealed, that the pressure applied during the application of the ground had caused it to be pushed through the canvas weave to form drips down the back. The ground contains calcium carbonate (chalk), lead white and charcoal black.2 It may be seen in figs.6 and 7.

Fig.6

Cross-section from Porter’s yellow jerkin, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: thin layer of glue-size applied to the canvas (which is not present in the sample); grey ground; thin, opaque dark reddish brown underpaint; yellow paint of jerkin; Paraloid B72 varnish

Fig.7

The same cross-section as fig.6 photographed in ultra-violet light

The painting has a detailed underpainting or dead colouring, although no linear underdrawing was detectable with infra-red reflectography (figs.8, 9 and 10).3 Stereomicroscopy of Porter’s face and hands, aided by cross-sections from the latter, indicate that these areas were fully modelled in opaque dark beige tones with plum colour for the deep shadows around the nose and mouth.

The boy’s robe, the dark foreground and the buff cloak were modelled in shades of mulberry brown and brick red, while the mustard yellow jerkin has shades of mulberry brown and opaque grey underneath it (figs.6, 7 and 11). The X-ray showed a zig-zag application of X-ray-dense paint running underneath the collar and jerkin at the left hand side, which would suggest that the grey constitutes deliberate underpaint rather than a change of mind regarding colour. The sculpture appears to have been laid in at first with dark brown paint. Examination with X-ray and infra-red reflectography did not reveal any pentimenti in the composition.

Fig.11

Detail of light grey underpaint in yellow jerkin, photographed at x10 magnification

The painting is characterised by dense, well-blended, opaque colours applied thinly in a creamy consistency that just retains the marks of the brush. A limited amount of impasto helps create the textured elements such as the braid on the cloak (fig.12), though a heavy lining in the past has depressed the impasto to some extent. Except in the mulberry brown shadow beneath the gun and some of the dark shadows in the cloak, the dead colouring was not left uncovered. In the dark recessive areas behind the figures and in most of the shadows of the cloak, it is glazed over with thin brown paint. Most of the tonal work throughout the composition was done wet-in-wet, with decorative detail − such as the stitching on the jerkin − applied on top after the main colour was touch-dry. The ribbons on the jerkin and the lining of its sleeves were first painted tonally with wet-in-wet mixtures of white and indigo.

Fig.12

Detail photographed at x8 magnification of the braid on the blue cloak

After drying they were glazed with translucent paint made from ultramarine mixed with a transparent pigment, probably chalk (figs.13 and 14).

Fig.13

Cross-section from mid-blue of costume, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom: ground; dark brown dead colouring; opaque pale blue paint of ribbon; blue glaze, containing ultramarine and chalk; Paraloid B72 varnish

Fig.14

The same cross-section as fig.13 in ultraviolet light

The blue lining of the jerkin was glazed with two types of blue – ultramarine and probably indigo on top of opaque pale blue paint (fig.15). Examination of the cross-sections in ultra-violet light indicates that all the colours are bound in pure oil, rather than oil mixed with resinous substances.

Fig.15

Detail photographed at x8 magnification of the lining of Porter’s cloak, showing two types of blue pigment – ultramarine and probably indigo – used as glazes over thick, opaque underpainting

The flesh-tones follow a pattern of pinkish shadows and mid-tones, followed by the application of cool opaque half-shadows and highlights. All the flesh-tones contain a large proportion of coarse black pigment and a smaller amount of ultramarine blue, the proportions of which increase in the pearly half-tones such as those around the eyes of both figures. The whites of the eyes also contain admixtures of ultramarine. As well as the coarse black pigment that occurs in the paint-mixtures throughout the picture, there is an admixture of pale smalt in most of the colours; the particles are small and are discernible only in dispersions at high magnification. The dispersions of all the colours show a noticeable absence of other fillers and extenders, apart from the transparent pigment in the blue mentioned above. At high magnification a feature of the flesh-tones and all other areas of a warm hue, including the statue, are very large clumps of the red pigment, vermilion (fig.16).

Fig.16

Detail photographed at x10 magnification of a flesh tone, showing large dark pigments and large red particles of vermilion

The sky was once a more uniform bright blue, having been painted first with a mixture of blue smalt, lead white and black, with the pink clouds brushed in while the blue was still wet. The smalt mixture has discoloured to the grey that we see. The area of bright blue round Porter’s head was put in last, probably after the figure was finished, and it contains a high proportion of ultramarine, which unlike the smalt has retained its original hue. There are indications that other areas of the sky were also finished with scumbles of ultramarine mixtures that have not survived intact, probably as a consequence of early methods of cleaning. Another change has been the fading of a crimson glaze over the boy’s coat (fig.17). By contrast a thickly applied red lake glaze is present over the gold chain worn by the boy attendant, and this is relatively well preserved (fig.18).

Fig.17

Detail of the boy’s red coat, photographed at x8 magnification, showing unfaded red lake glaze paint in the hollows of the paint film; the glaze has faded in the other areas

Fig.18

Detail of the boy’s chain, photographed at x8 magnification, showing unfaded red lake paint

On balance the painting is in good condition. Apart from the changes discussed above, its principal mode of deterioration has been to develop a tight network of age-cracks whose scale relates directly to the canvas weave. In many areas there are pin-head sized losses of the ground and paint on these cracks as they pass over the tops of the threads. A similar condition is present in Dobson’s earlier portrait of his wife, Judith (Tate T06640). There are pustules relating to the formation of lead soap aggregates in areas of the boy’s red coat but none elsewhere.4

The painting was cleaned and relined in 1970. The varnish is a modern synthetic resin.

March 2005