Fig.1

Gilbert Jackson (active 1621–1642)

A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son 1640

Tate

T03237

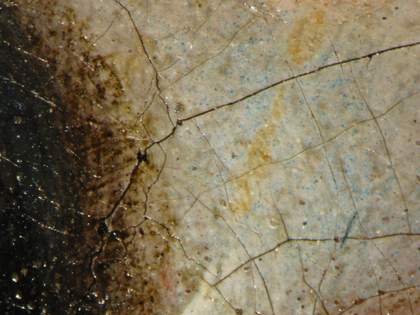

Fig.2

Detail of the woman’s head in A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son 1640

Fig.3

Detail of the child’s head in A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son 1640

Fig.4

Detail of lower left corner of A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son 1640

and the signature

Fig.5

X-radiograph of A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son 1640

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 742 x 608 mm (figs.1–4). The single piece of plain woven linen is rather fine with an average of 13 vertical and 14 horizontal threads per square centimetre. The tacking edges are no longer present but cusping on all four sides indicates that the composition has not been reduced in size (fig.5).1 There is no evidence of stretcher bar marks to suggest the shape or style of the original stretcher or strainer. The painting is now lined with glue paste adhesive and canvas. The X-ray dense, patchy areas in the left background of the painting appeared at first to relate to old, restored damages in the paint layer. However, given the consistency of the paint across the entire background, it is likely that the artist used a canvas with a slightly damaged ground and merely filled the losses in it before starting to paint the composition.

The ground is a single, translucent, chalk-rich layer bound in oil. It is a warm, slightly orange colour and besides chalk it contains lead white, bone black, fine red lead, a little earth colour and vermilion.2 This is a thin layer, probably applied to fill the canvas weave in preparation for the grey priming.

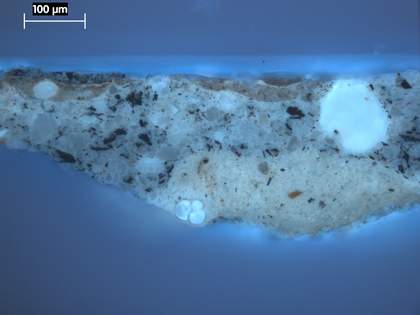

Fig.6

Cross-section taken from the brown background at the left edge, 40 mm from the bottom, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: chalk rich ground; grey priming; dark brown paint; grey paint; varnish

Fig.7

The same cross-section as in fig.5, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light. The bright white spheres are lead soap aggregates

The oil bound priming is composed of a single, even layer made up of lead white and charcoal black modified with the addition of red lead, and a little vermilion and earth colours. This layer was found to be developing lead soap aggregates, which are visible in figs.6–7.

Fig.8

Infrared reflectograph detail of the woman’s head

Fig.9

Infrared reflectograph detail of the woman’s hand in the lower left corner

No underdrawing was visible in infrared reflectography (figs.8–9). It seems likely that the artist used a warm, dark brown wash of thin paint to lay in the features of the sitters but otherwise the composition appears to have developed haphazardly with many pentimenti.

Fig.10

Cross-section from the metal button on the red chair at the right edge, 330 mm from the bottom, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: chalk rich ground; grey priming; pale brown paint of background; opaque orangey red paint of chair; red glaze on chair; yellowish brown paint of chair button; opaque yellow highlight on button

Fig.11

The same cross-section as in fig.7, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light

Paint thicknesses and applications vary from the single layer, wet-in-wet modulation of the child’s white dress to the five-layer build-up of the button detail on the red chair (figs.10–11). The grey priming does not play any visible part in the composition. The irregular development of the composition is demonstrated in many areas: the chair was painted on top of the brown background instead of having had a reserve left for it (figs.10–11); the pearl necklace was painted on top of the flesh paint of the woman’s neck; the child’s yellow jacket was added on top of his white robe; the woman’s left hand was painted before the yellow jacket but after the white robe, which is also the case for her right hand, which sits on top of the white dress; the child’s right hand was superimposed over the woman’s arm; the woman’s pink sleeve extends over her brown bodice and the child’s collar and bonnet extend over the background. More changes occurred to the portrait of the child than the woman and the infant’s profile was altered (fig.5).

Fig.12

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the original yellow colour a pink tulip

Fig.13

Photomicrograph at x 15 magnification of blue pigment in a half-shadow of a flesh tone

Fig.14

Photomicrograph at x15 magnification of blue pigment in the white of the child’s right eye

The artist made many alterations to the flowers in the woman’s hair, an interesting feature given the high cost of tulips in this period (see catalogue entry): a petal belonging to the top tulip was painted out and one added to the tulip at the bottom (fig.8). The colour of the middle, pink tulip has been altered. Paint visible at the edges of the flower petals shows that it was originally yellow and red like the lowest tulip (fig.12). The uppermost tulip was added over the background at a later stage.

The colours were mixed as follows: the opaque red of the chair contains vermilion, red lead, lead white, bone black, chalk, traces of china clay and its glaze is an aluminium-based red lake mixed with chalk; the greyish brown background was mixed from lead white, a range of earth colours, china clay, vermilion, Cologne earth, black and glassy material; the yellow highlights on the jewels and chair studs are mainly lead tin yellow mixed with chalk, lead white and earth colours. Azurite was missed into the flesh tones for half-shadows and mixed with lead white for the whites of the eyes (figs.13–14) and the pearls. Verdigris is present in the greens. Some of the glazes of red lake have suffered some fading, for example in the woman’s pink sleeve.

The unusually large number of paint layers that results from painting compositional elements one on top of another, with lead white used in every layer, have led to the formation of numerous lead soap aggregates in all the paint layers as well as in the priming, as can be seen in figs.10–11. This is unusual, being generally seen only in paint containing lead-tin yellow or red lead. Fortunately the aggregates have neither grown large nor disrupted the paint surface by breaking through it. Detailed chemical analyses of the cross-section taken through the button on the red chair (fig.10) have been published in a text which discusses the mechanisms of lead soap formation.3

The painting was cleaned at Tate in 1981. The varnish is a modern synthetic resin.

August 2020