To celebrate Women in Revolt! at Tate Britain, we invited nine women to discuss their experiences of making feminist art in 1970s and 1980s Britain, and the social and artistic barriers they fought to overcome.

In the second conversation, which focuses on working in a multiplicity of ways – as makers, curators, educators, fundraisers, and more – Rita Keegan points to the urgency of being recognised and represented as a motivating factor for making art, but also the simultaneous need to find and keep paid employment. For many women, as Stella Dadzie discusses, earning a living through art alone was not an option. Instead, the women included here worked in community settings, or taught, in order to survive and continue to make art.

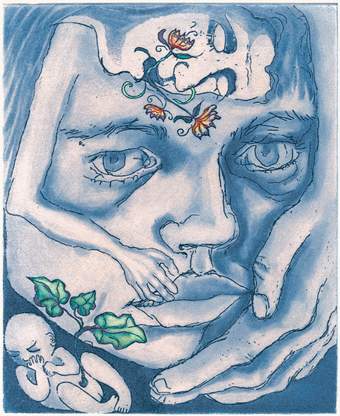

Stella Dadzie

Motherland c.1984

© Stella Dadzie. Courtesy the artist

MARLENE SMITH Stella, you were a co-founder of Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD). What led up to its formation?

STELLA DADZIE It was during the mid-1970s, when civil rights activities were already ongoing in the UK, and to some extent Black women were already involved. But some women were beginning to feel frustrated, partly by the fact that the issues that concerned us were taking second place – but also there was a sense that we needed our own voice.

We were thinking about forming a caucus with another organisation, but we soon decided that we needed to be independent. And although we started off as women of Africa and African descent, we realised that we should include Asian women. An Asian sister turned up at one of our early meetings in motorbike leathers and said: ‘What about us?’ She was from a family that had been expelled from East Africa, so she saw herself as African. And she pointed out that Asian women were facing similar issues in this country.

MS What kind of numbers of people were gathering and how often were you meeting?

SD We started with a conference organised through our grapevines, so we had no idea how many people would turn up. But nearly 300 Black and brown women came. It was London-centric but there were women from other parts of the UK too.

Although we were coming together as Black women, the issues concerning us were education, police brutality and our treatment within the National Health Service – issues that affected men in our communities too. That’s what made our feminism distinct from what white women were doing, which only focused on gender and patriarchy. It reflected our reality – that racism blighted our lives as much, if not more, than class and sexism.

RITA KEEGAN All those issues were crucial in the meetings that I was part of, too. I was a founding member of the Brixton Art Gallery, which was established in 1983, and then later Women’s Work, Black Women in View and the Black Women Artists collective.

All of these groups had a strong educational outreach, we were talking about issues of health, and we were quite global. For the most part, Black feminism had the same issues, but also more issues. We lived within the world.

SD It’s like the Alice Walker quote, isn’t it? ‘Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.’ That was reflected in our politics and our actions. If we heard that someone had been arrested, we would gather round that police station and say ‘No’. You mentioned that global perspective, which is the other thing that made us distinct. We had an anti-imperialist lens; we recognised the connections between here and there.

RK Well, maybe that was because we were from different places, but still the same place. You had African women, you had African-Asian women. You were united by your melanin and not necessarily your geography.

SD A lot of the texts we were studying were socialist texts, Marxist, Leninist texts, so there was a sense of needing to develop solidarity with other Black and brown people across the diaspora. We used the term Black to denote that. It was more about our shared experience of racism.

Rita Keegan

Red Me 1986

© Rita Keegan. Courtesy the artist and the Government Art Collection

RK I’ve had to explain that to a lot of younger people – it was Black in the political sense. All of us came from a situation where, on an official form, you were ‘non-white’; you were ‘non’, and the ownership of the term Black was a positive and unifying thing.

SD That’s right, and the context was ‘Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud’. We were influenced by what was happening in the United States and by the national liberation struggles across the African diaspora.

MS When OWAAD and other Black feminist groups came together, what was the reaction of the men?

SD It was everything from accusing us of splitting the struggle to coming to our conferences and running the book stall or the creche. There were also men who thought we were imitating what white women were doing and accused us of being a bunch of lesbians.

But over the years, I think we proved ourselves. From the Black People’s Day of Action to the Brixton Defence campaign, the men may have been the ones standing on soapboxes, but it was the women doing the work behind the scenes.

MS What about women artists, what role did they play in the early feminist movement?

RK Our role was incredibly active, whether it was organising exhibitions or the day-to-day running of Brixton Art Gallery. It wasn’t just work on walls – the gallery was a space for the arts more broadly: we would have poetry, performance, dancing and drumming. We fostered an inclusiveness that is prevalent within Black women’s art practice for the most part. Even if we weren’t putting on shows ourselves, we wanted to empower other people. If men wanted to have a show, we were there to encourage that. And we were always multigenerational, trying to bring in the old as well as the young.

SD One of the things that will be included in the exhibition is a Sister OWAADA cartoon about issues faced by Black women, which I drew for our newsletter FOWAAD! Our political concerns fed our creative spirit and became both our muse and our voice.

MS Rita, I can still hear your American accent. How did you become involved with Brixton Art Gallery?

RK My mother was from Dominica and my father was Canadian. I say that I am American in the sense of the Americas. Culturally, it wasn’t a big leap, but I got treated like a foreigner. But then I was treated like a foreigner in America too, so it made it easy to just be me.

As for Brixton Art Gallery, I moved to Brixton in 1982, and met some of the people who had started it. I got involved, and we made it into a collective. I don’t know how not to volunteer. I wish I did but I don’t. I ended up learning about the process of exhibiting, hanging work, press releases – just demystifying the whole process. Then I got involved in the Women Artists Slide Library, establishing the Women of Colour Index, and after that, the Arts Council, looking at this country’s art policy.

Issue no.2 of FOWAAD!, a newsletter by activist organisation OWAAD. This issue from 1979 sheds light on a protest by South Asian women

Courtesy the Feminist Library

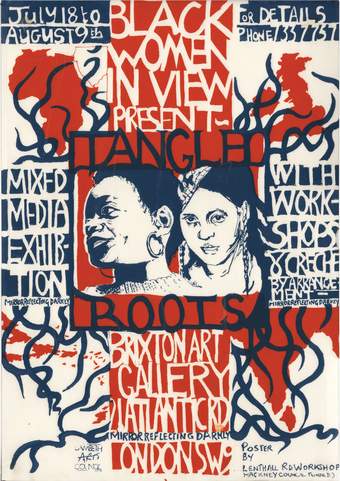

A poster by Lenthall Road Workshop promoting the exhibition Tangled Roots at Brixton Art Gallery, 1986

Courtesy Brixton Art Gallery Archive

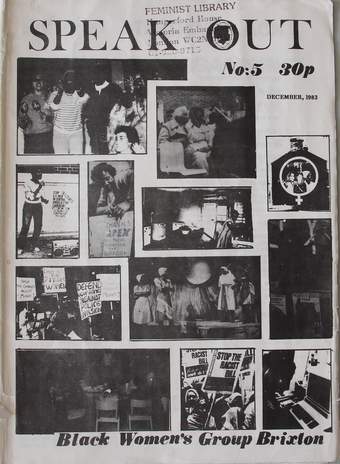

Issue no 5 of Speak Out, a newsletter by Brixton Black Women's Group, published in December 1983

MS All those different roles, organising, curating, working with the Arts Council – why do that range of activity?

RK It was about ownership of the process, which tied in with showing my work. But with the Arts Council, I knew that if I didn’t sit at that table, there might not have been somebody there who looked like me. If I didn’t give my voice, I couldn’t accuse them of not listening.

I still made art, but you’re not making it 24/7 and I never had the luxury of a studio that was magically paid for, or even inexpensive. I was always trying to find a way to work: for instance, a photocopier was a way of doing printmaking without having a dedicated studio. You could use the photocopier in an almost transgressive way, and you could store the resulting piece in an A4 folder. That has been a common experience for most of us – our practice has had to fit into our lives, as opposed to our lives fitting into our practice.

SD What Rita’s saying resonates. My mother was an artist, and art was always where I went when I had a delicious moment of time. But I used to fear that creative spirit, because once I got engaged in something, I could forget what time it was; suddenly the birds were singing and I’d worked through the night. Because I had to juggle a career and childcare as a single parent, I would stop myself from doing something creative. I worried it would get in the way of real life. It’s part of how women create art – particularly Black women who have to earn a living, who juggle all kinds of other things.

RK No matter what you do, you make choices that you have to live with. I thought that that was just women, but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realised that it’s part of the human condition. Even men don’t have it all. Choice is a blessing and a curse, but the lack of choice is even worse. For many of our mothers, what they had was a given and their choices were few.

MS Stella, your mother was an artist too.

SD Yes, she got a scholarship, but the war intervened, and she ended up having to use her skills as a draughtswoman. My abiding memory is of her working on drawing boards with blue wax rolls on which would be drawn plans of buildings. That’s my abiding memory of my mother’s creative output, because that’s what she did to pay the rent.

RK Our mothers had to find different ways of doing it. My great grandmother was an amazing seamstress who also liked to take family photos. She is the reason I have wealth of family photos from 1880 to now. She had an amazing eye, but there was no way that she would have had the chance to go into the arts. Her creativity had to go into making practical things.

MS It brings to mind Alice Walker’s book In Search of our Mothers’ Gardens (1983), in which she talks about watching her mother composing her garden, choosing the colours, the sizes, the shapes. I’ve made a few pieces using plastic flowers and crochet that are about my mother’s creativity. In Art History 1987, which will be in the show, I’m asking what we count as art, and who do we name when we’re putting together art histories?

RK That’s also why the home is so important. How our mothers served up the cake or arranged the vase with flowers. How they dressed you for Sunday, arranged the Christmas tree, made the crochet doilies. The home was their canvas.

With Tate acquiring my work, a little girl that looks like the three of us will walk into a museum and look at an image of another little girl who won’t be a slave, won’t be a maid: she will be herself. It’s important that we are recognised and represented, that our creativity can go on to inspire someone else or even just be part of the texture.

Marlene Smith

Art History, 1987

© Marlene Smith

MS Who was the first Black artist you encountered?

RK Growing up in New York, I was always aware of the Harlem Renaissance, so I heard about the sculptor Augusta Savage. And my uncle Keith, who lived in our apartment, was a painter. I grew up with the smell of turpentine. I grew up knowing that it was something that I could be.

But I was lucky. I went to an art high school in Midtown Manhattan, so I would, aged 13 or 14, spend the afternoon going to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I might have been watched, but maybe the guards were just amused that there was this strange little Black kid wandering around.

MS What about you, Stella?

SD Certain exhibitions stand out. I remember Keith Piper’s Past Imperfect, Future Tense 1984 at the Black-Art Gallery in Finsbury Park. But it’s difficult to pinpoint one artist. I spent my teenage years and twenties visiting Ghana, where my father’s from, which is a hugely creative country. There’s art on the street; there are carvings, paintings, jewellery, Adinkra symbols, kente cloth. I feel I’ve been bombarded by different kinds of art throughout my life. When did you start being creative, Marlene?

MS I was always drawing when I was little, but it wasn’t until I was a teenager that I started to take it a bit more seriously. I was at a girls’ grammar school in Handsworth and I found myself doing A level art. As part of that, I did a written project on Black artists in Britain, and spent a lot of time between the ages of 17 and 18 trying to track down Black artists in Britain. I wrote to the sculptor Ronald Moody and also got in touch with the painter Frank Bowling, and with Shakka Dedi who opened the Black-Art Gallery. I was lucky to find a Black arts community at a tender age. I think it’s possible to go through your whole life without even knowing it’s there.

RK Knowing that you are not inventing the wheel is so important. When you meet somebody young and they say: ‘I’ve seen your work, you really made something’, I often think: ‘Oh, did I?’ Maybe my life wasn’t a waste. Maybe the ripples in the pond are bigger than I thought.

Marlene Smith is an artist and curator.

Stella Dadzie is an educator, activist, writer and feminist historian.

Rita Keegan is an artist, lecturer and archivist.